ハロタン

| |

| |

| IUPAC命名法による物質名 | |

|---|---|

| |

| 臨床データ | |

| 販売名 | フローセン(Fluothane) |

| Drugs.com |

専門家向け情報(英語) FDA Professional Drug Information |

| ライセンス | US Daily Med:リンク |

| 法的規制 | |

| 薬物動態データ | |

| 代謝 | 肝臓 (CYP2E1[4]) |

| 排泄 | 腎臓、呼吸器 |

| データベースID | |

| CAS番号 |

151-67-7 |

| ATCコード | N01AB01 (WHO) |

| PubChem | CID: 3562 |

| IUPHAR/BPS | 2401 |

| DrugBank |

DB01159 |

| ChemSpider |

3441 |

| UNII |

UQT9G45D1P |

| KEGG |

D00542 |

| ChEBI |

CHEBI:5615 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL931 |

| 別名 | ハロセン |

| 化学的データ | |

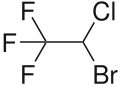

| 化学式 | C2HBrClF3 |

| 分子量 | 197.38 g·mol−1 |

| |

| 物理的データ | |

| 密度 | 1.871 g/cm3 (at 20 °C) |

| 融点 | −118 °C (−180 °F) |

| 沸点 | 50.2 °C (122.4 °F) |

ハロタン(Halothane、別名: ハロセン[5])は吸入によって投与される[6]揮発性麻酔薬の一種である[6]。麻酔の導入や維持に使用される[6]。気管支拡張作用は強いが、鎮痛効果と筋弛緩作用は強くはない。甘い匂いを持ち、吸入による麻酔導入に適している。

副作用には不整脈、呼吸抑制、肝毒性がある[6]。他の揮発性麻酔薬と同様に、悪性高熱症の個人歴や家族歴がある患者には使用すべきではない[6]。

ハロタンは1951年に発見された[7]。世界保健機関の必須医薬品リストに掲載されている[8]。かつて、多くの国で用いられたが、先進国では、より新しい麻酔薬であるセボフルランなどにとってかわられている[9]。ハロタンは地球温暖化ガスであり、オゾン層破壊物質でもあるが、実際の影響は小さい。

医療用途

[編集]

最小肺胞内濃度(MAC)が0.74%の強力な麻酔薬である[10]。血液/ガス分配係数が2.4であることから、導入と回復に中程度の時間を要する薬剤である[11]。鎮痛効果は乏しく、筋弛緩効果は中程度である[12]。唾液の産生を増加させない[注釈 1]という利点があり、これは挿管が困難な患者で特に有用であるとWHOの処方に記載されていた[6]が、後に開発された揮発性麻酔薬セボフルランには、ほとんど勝るところがない[13][14]。

ハロタンは麻酔用気化器では赤色でコード化されている[15]。

副作用

[編集]副作用には不整脈、呼吸抑制、肝毒性がある[6]。ポルフィリン症では安全に使用できるようである[16]。妊娠中の使用が胎児に有害かどうかは不明で、帝王切開での使用は一般的には推奨されない[17]。

稀な例として、成人でのハロタンへの繰り返しの曝露により重度の肝臓障害が発生することがある。これは約10,000回の曝露のうち1回の割合で発生する。この症候群はハロタン肝炎と呼ばれ、免疫アレルギー性の原因によるものである[18]。これは肝臓での酸化反応によってハロタンがトリフルオロ酢酸に代謝されることが原因と考えられている。吸入されたハロタンの約20%が肝臓で代謝され、これらの代謝産物は尿中に排泄される。この肝炎症候群の死亡率は30%から70%である[19]。

肝炎への懸念から1980年代にはハロタンの成人での使用は劇的に減少し、エンフルランとイソフルランにとってかわられた[20][21]。 2005年には、最もよく使われる揮発性麻酔薬はイソフルラン、セボフルラン、デスフルランとなっていた。小児でのハロタン肝炎のリスクは成人と比べて大幅に低く、吸入による麻酔導入に特に有用であることから、1990年代も小児麻酔で使用され続けた[22][23]。しかし2000年までには、吸入による麻酔導入に優れたセボフルランにより、小児でのハロタンの使用も大半がとってかわられた[24]。

ハロタンは心臓をカテコールアミンに対して感作するため、特に高炭酸ガス血症が進行している場合には、時に致命的な不整脈を引き起こす可能性がある。歯科の外来での小児を対象としたランダム化比較試験では、不整脈の発生率はセボフルランの28%に対して、ハロタンは62%に達し、有意に高かった[25]。

他の吸入麻酔薬と同様に、ハロタンは悪性高熱症の強力な引き金となる[6]。同様に、他の吸入麻酔薬と同様に、子宮平滑筋を弛緩させ、分娩や妊娠中絶時の出血量を増加させる可能性がある[26]。

労働安全

[編集]この麻酔薬が使われる環境では、人々は廃棄麻酔ガスの吸入、皮膚接触、眼への接触、または飲み込みによって職場でハロタンに曝露される可能性がある[27]。アメリカ 国立労働安全衛生研究所(NIOSH)は60分間で2 ppm(16.2 mg/m3)の推奨曝露限界を設定している[28]。

薬理学

[編集]揮発性麻酔薬の作用の正確な機序はまだ解明されていない[29]。ハロタンはGABAA受容体とグリシン受容体を活性化する[30][31]。また、NMDA受容体拮抗薬として作用し、[31]ニコチン性アセチルコリン受容体と電位依存性ナトリウムチャネルを阻害し[30][32]、5-HT3受容体とタンデムポア型カリウムチャネルを活性化する[30][33]。AMPA型グルタミン酸受容体またはカイニン酸型グルタミン酸受容体には影響を与えない[31]。

化学的および物理的性質

[編集]ハロタン(2-ブロモ-2-クロロ-1,1,1-トリフルオロエタン)は、密度が高く、高い揮発性を持つ、無色透明の不燃性液体で、クロロホルム様の甘い臭いがする。水にはごくわずかしか溶けないが、様々な有機溶媒と混和する。ハロタンは光と熱の存在下でフッ化水素、塩化水素、臭化水素に分解する可能性がある[34]。

| 沸点: | 50.2°C | (101.325 kPaにて) |

| 密度: | 1.871 g/cm3 | (20°Cにて) |

| 分子量: | 197.4 u | |

| 蒸気圧: | 244 mmHg (32kPa) | (20°Cにて) |

| 288 mmHg (38kPa) | (24°Cにて) | |

| MAC: | 0.75 | vol % |

| 血液:ガス分配係数: | 2.3 | |

| 油:ガス分配係数: | 224 |

化学的に、ハロタンはハロゲン化アルキルであり(多くの他の麻酔薬のようなエーテルではない)[4]。ハロタンはキラル分子で、ラセミ体として使用される[35]。

合成

[編集]ハロタンの工業的合成はトリクロロエチレンから始まり、これを三塩化アンチモン存在下、130°Cでフッ化水素と反応させて2-クロロ-1,1,1-トリフルオロエタンを生成する。これを450°Cで臭素と反応させてハロタンを生成する[36]。

関連物質

[編集]代謝が少ない麻酔薬を探す試みから、エンフルランやイソフルランなどのハロゲン化エーテルが開発された。これらの薬剤では肝臓への反応の発生率は低い。エンフルランの肝毒性の可能性については議論があるが、代謝はごく僅かである。イソフルランはほとんど代謝されず、関連する肝障害の報告は非常に稀である[37]。ハロタンとイソフルランの代謝から少量のトリフルオロ酢酸が生成される可能性があり、これがこれらの薬剤間での交差感作の原因である可能性がある[38][39]。

より現代的な薬剤の主な利点は、血液溶解度が低いことで、これにより麻酔の導入と回復がより速やかになる[40]。

歴史

[編集]

ハロタンは1951年にインペリアル・ケミカル・インダストリーズ(ICI)のC. W. サックリングによってICI ウィドニス研究所で最初に合成され、1956年にマンチェスターのM. ジョンストンによって初めて臨床使用された。1958年にアメリカ合衆国で医療用として承認された[3]。

当初、多くの薬理学者と麻酔科医はこの新薬の安全性と有効性に疑問を持っていた。しかし、安全な投与のために専門的な知識と技術を必要とするハロタンの登場は、当時、より多くの専門医を必要としていた新設の英国国民保健サービス(NHS)の時期に、英国の麻酔科医が自分たちの専門性を職業として再構築する契機となった[41]。このような状況の中で、ハロタンは最終的にトリクロロエチレン、ジエチルエーテル、シクロプロパンなどの他の揮発性麻酔薬に代わる不燃性の全身麻酔薬として普及した[注釈 2]。世界の多くの地域で1980年代以降、より新しい薬剤に大半が取って代わられているが、コストが低いため発展途上国では依然として広く使用されている(2008年)[42]。

ハロタンは1956年の導入から1980年代にかけて、世界中で数百万人に投与された[43]。その特性には、高濃度での心臓抑制、カテコールアミン(ノルエピネフリンなど)に対する心臓の感作、強力な気管支弛緩作用がある。気道刺激性が低いことから、小児麻酔での吸入による麻酔導入に一般的に使用された[44][45]。

先進国では、セボフルランなどのより新しい麻酔薬にそのほとんどが置き換えられている[46]。アメリカ合衆国では現在市販されていない[17]。日本では、1959年10月から販売されていたが、2015年8月に販売中止がアナウンスされた[47]。

社会と文化

[編集]入手可能性

[編集]世界保健機関の必須医薬品リストに掲載されている[8]。30、50、200、250 mlの容器で揮発性液体として入手可能だが、多くの先進国では新しい薬剤に置き換えられて入手できない[48]。

臭素を含む唯一の吸入麻酔薬であり、これにより放射線不透過性となる[49]。無色で快い香りがするが、光に不安定である。暗色の瓶に充填され、安定剤として0.01%のチモールを含有している[20]。

温室効果ガス

[編集]共有結合したフッ素の存在により、ハロタンは大気の窓で吸光を示すため温室効果ガスである。しかし、多くのクロロフルオロカーボンやブロモフルオロカーボンと比べると、大気中での寿命が約1年と短いため(多くのパーフルオロカーボンは100年以上)、その効果は大幅に弱い[50]。

短い寿命にもかかわらず、ハロタンの地球温暖化係数(global warming potential: GWP)は二酸化炭素の47倍だが、これは最も一般的なフッ素化ガスの100分の1以下であり、500年間での六フッ化硫黄のGWPの約800分の1である[51]。ハロタンは地球温暖化への寄与は無視できる程度と考えられている[50]。

オゾン層破壊

[編集]ハロタンはODPが1.56のオゾン層破壊物質で、成層圏オゾン層破壊全体の1%の責任があると計算されている[52][53]。

脚注

[編集]注釈

[編集]出典

[編集]- ^ Anvisa (31 March 2023). “RDC Nº 784 — Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial” [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 — Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (ポルトガル語). Diário Oficial da União. 3 August 2023時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。16 August 2023閲覧。

- ^ “Halothane, USP”. DailyMed (18 September 2013). 11 February 2022閲覧。

- ^ a b “Fluothane: FDA-Approved Drugs”. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 12 February 2022閲覧。

- ^ a b “Halothane”. DrugBank. 2024年11月13日閲覧。

- ^ “ハロタンとは”. コトバンク. 2022年9月27日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f g h ((World Health Organization)) (2009). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. pp. 17–8. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 978-92-4-154765-9

- ^ Trends and Changes in Drug Research and Development. Springer. (2012). p. 109. ISBN 978-94-009-2659-2. オリジナルの10 September 2017時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ a b The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: web annex A: World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 23rd list (2023). Geneva: World Health Organization. (2023). hdl:10665/371090. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02

- ^ Anaesthesia and Intensive Care A-Z: An Encyclopedia of Principles and Practice (5th ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. (2013). p. 264. ISBN 978-0-7020-5375-7. オリジナルの10 September 2017時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ Minimum Alveolar Concentration. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. (2022). PMID 30422569. NBK532974

- ^ “The blood–gas partition coefficient”. Southern African Journal of Anaesthesia and Analgesia 1 (3): 3. (November 2020). doi:10.36303/SAJAA.2020.26.6.S3.2528. ISSN 2220-1181.

- ^ “Halothane”. Anesthesia General (31 October 2010). 16 February 2011時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2024年11月13日閲覧。

- ^ Kangralkar, Gouri; Jamale, Parbati Baburao (2021-06). “Sevoflurane versus halothane for induction of anesthesia in pediatric and adult patients” (英語). Medical Gas Research 11 (2): 53. doi:10.4103/2045-9912.311489. PMC PMC8130664. PMID 33818443.

- ^ Abubakar, Ballah; Sadiq, A.; Sambo, Tanimu Y. (2021). Intubation without Muscle Relaxants: Sevoflurane Vs Halothane, A Comparison of Intubation Characteristics.

- ^ “Safety features in anaesthesia machine”. Indian J Anaesth 57 (5): 472–480. (September 2013). doi:10.4103/0019-5049.120143. PMC 3821264. PMID 24249880.

- ^ “Porphyrias”. British Journal of Anaesthesia 85 (1): 143–53. (July 2000). doi:10.1093/bja/85.1.143. PMID 10928003.

- ^ a b “Halothane — FDA prescribing information, side effects and uses”. www.drugs.com (June 2005). 21 December 2016時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。13 December 2016閲覧。

- ^ Halothane. LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]. (January 2018). PMID 31643481. NBK548151

- ^ “Halothane metabolism in children”. British Journal of Anaesthesia 64 (4): 474–481. (April 1990). doi:10.1093/bja/64.4.474. PMID 2334622.

- ^ a b Halothane Toxicity. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. (2022). PMID 31424865. NBK545281

- ^ “Determination of the halothane metabolites trifluoroacetic acid and bromide in plasma and urine by ion chromatography”. Journal of Chromatography B: Biomedical Sciences and Applications 692 (2): 413–8. (9 May 1997). doi:10.1016/S0378-4347(96)00527-0. ISSN 0378-4347. PMID 9188831.

- ^ “Volatile anesthetics isoflurane and sevoflurane directly target and attenuate Toll-like receptor 4 system”. FASEB Journal 33 (12): 14528–41. (December 2019). doi:10.1096/fj.201901570R. PMC 6894077. PMID 31675483.

- ^ “Inhalation anesthesiology and volatile liquid anesthetics: focus on isoflurane, desflurane, and sevoflurane”. Pharmacotherapy 25 (12): 1773–88. (December 2005). doi:10.1592/phco.2005.25.12.1773. PMID 16305297.

- ^ “Sevoflurane. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and its clinical use in general anaesthesia”. Drugs 51 (4): 658–700. (April 1996). doi:10.2165/00003495-199651040-00009. PMID 8706599.

- ^ “Comparison of sevoflurane and halothane for outpatient dental anaesthesia in children”. British Journal of Anaesthesia 79 (3): 280–4. (September 1997). doi:10.1093/bja/79.3.280. PMID 9389840.

- ^ “Potent Inhalational Anesthetics for Dentistry”. Anesthesia Progress 63 (1): 42–8; quiz 49. (2016). doi:10.2344/0003-3006-63.1.42. PMC 4751520. PMID 26866411.

- ^ “Common Name: Halothene”. Hazardous Substance Fact Sheet 969 (1). (1999).

- ^ “Halothane”. NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. (NIOSH) National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Centers for Disease Control. 8 December 2015時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。3 November 2015閲覧。

- ^ “How does anesthesia work?”. Scientific American (7 February 2005). 30 June 2016閲覧。

- ^ a b c Foundations of Anesthesia: Basic Sciences for Clinical Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. (2006). pp. 292–. ISBN 978-0-323-03707-5. オリジナルの30 April 2016時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ a b c Clinical Anesthesia, 7e: Print + Ebook with Multimedia. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. (7 February 2013). pp. 116–. ISBN 978-1-4698-3027-8. オリジナルの17 June 2016時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ Modern Anesthetics. Springer. (8 January 2008). pp. 70–. ISBN 978-3-540-74806-9. オリジナルの1 May 2016時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ Allosteric Receptor Modulation in Drug Targeting. CRC Press. (19 June 2006). pp. 143–. ISBN 978-1-4200-1618-5. オリジナルの10 May 2016時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ Lewis, R.J. Sax's Dangerous Properties of Industrial Materials. 9th ed. Volumes 1-3. New York, NY: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1996., p. 1761

- ^ The Anaesthesia Science Viva Book. Cambridge University Press. (17 June 2004). p. 161. ISBN 978-0-521-68248-0. オリジナルの10 September 2017時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ “Process for the preparation of 1, 1, 1-trifluoro-2-bromo-2-chloroethane”. Google Patents. 2024年11月13日閲覧。

- ^ Halogenated Anesthetics. LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury. (January 2018). PMID 31644158. NBK548851

- ^ “Effects of trifluoroacetic acid, a halothane metabolite, on C6 glioma cells”. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health 31 (2): 147–158. (October 1990). Bibcode: 1990JTEH...31..147M. doi:10.1080/15287399009531444. PMID 2213926.

- ^ “Metabolism of halothane in obese Fischer 344 rats”. Anesthesiology 71 (3): 431–7. (September 1989). doi:10.1097/00000542-198909000-00020. PMID 2774271.

- ^ “The pharmacology of isoflurane”. British Journal of Anaesthesia 56 (Suppl 1): 71S–99S. (1984). PMID 6391530.

- ^ “Medicating Anaesthesiology: Pharmaceutical Change, Specialisation and Healthcare Reform in Post-War Britain”. Social History of Medicine 34 (4): 1343–65. (March 2021). doi:10.1093/shm/hkaa101.

- ^ “Inhalation Anaesthesia: From Diethyl Ether to Xenon”. Modern Anesthetics. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. 182. (2008). pp. 121–142. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-74806-9_6. ISBN 978-3-540-72813-9. PMID 18175089

- ^ Electroencephalography: Basic Principles, Clinical Applications, and Related Fields. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. (2005). p. 1156. ISBN 978-0-7817-5126-1. オリジナルの9 May 2016時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ “Mechanisms involved in cardiac sensitization by volatile anesthetics: general applicability to halogenated hydrocarbons?”. Critical Reviews in Toxicology 38 (9): 773–803. (2008). doi:10.1080/10408440802237664. PMID 18941968.

- ^ “Psychometric properties of the Cardiac Depression Scale: a systematic review”. Heart, Lung & Circulation 23 (7): 610–8. (July 2014). doi:10.1016/j.hlc.2014.02.020. PMID 24709392.

- ^ (英語) Anaesthesia and Intensive Care A-Z: An Encyclopedia of Principles and Practice (5th ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. (2013). p. 264. ISBN 978-0-7020-5375-7. オリジナルの10 September 2017時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ “全麻薬フローセン販売中止へ”. m3.com (2015年8月14日). 2015年9月26日閲覧。

- ^ National formulary of India (4th ed.). New Delhi, India: Indian Pharmacopoeia Commission. (2011). p. 411

- ^ Inhalational Anesthetic. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. (2022). PMID 32119427. NBK554540

- ^ a b “Global warming potentials and radiative efficiencies of halocarbons and related compounds: A comprehensive review”. Reviews of Geophysics 51 (2): 300–378. (24 April 2013). Bibcode: 2013RvGeo..51..300H. doi:10.1002/rog.20013.

- ^ “Updated Global Warming Potentials and Radiative Efficiencies of Halocarbons and Other Weak Atmospheric Absorbers”. Reviews of Geophysics 58 (3): e2019RG000691. (September 2020). Bibcode: 2020RvGeo..5800691H. doi:10.1029/2019RG000691. PMC 7518032. PMID 33015672.

- ^ Pharmaceuticals in the Environment: Sources, Fate, Effects and Risks. Springer. (2013). pp. 33. ISBN 978-3-662-09259-0

- ^ “Volatile anaesthetics and the atmosphere: atmospheric lifetimes and atmospheric effects of halothane, enflurane, isoflurane, desflurane and sevoflurane”. British Journal of Anaesthesia 82 (1): 66–73. (January 1999). doi:10.1093/bja/82.1.66. PMID 10325839.