利用者:加藤勝憲/メモリセル

メモリセルは、コンピューター・メモリーの基本的な構成要素である。メモリ・セルは1ビットの2進情報を記憶する電子回路であり、論理1(高電圧レベル)を記憶するように設定され、論理0(低電圧レベル)を記憶するようにリセットされなければならない。その値は維持される。

概要

[編集]メモリセルはメモリの基本的な構成要素である。バイポーラ、MOSFET、その他の半導体素子など、さまざまな技術を用いて実装することができる。また、フェライトコアや磁気バブルのような磁性材料から構築することもできる[1]。使用される実装技術にかかわらず、バイナリ・メモリ・セルの目的は常に同じである。セルを読み出すことでアクセスできる1ビットのバイナリ情報を記憶し、1を記憶するにはセットし、0を記憶するにはリセットする必要がある[2]。

メモリ素子の歴史

[編集]コンピューティングの歴史の中で、磁気コアメモリや磁気バブルメモリなど、さまざまなメモリセル・アーキテクチャが使われてきた。今日、最も一般的なメモリセルアーキテクチャは、金属酸化膜半導体(MOS)メモリセルで構成されるMOSメモリである。現代のランダム・アクセス・メモリ(RAM)は、MOS電界効果トランジスタ(MOSFET)をフリップフロップとして使用し、ある種のRAMにはMOSキャパシタも使用する。

SRAM(スタティックRAM)メモリセルはフリップフロップ回路の一種であり、通常はMOSFETを用いて実装される。アクセスされていないときに記憶値を保持するため、非常に低い電力を必要とする。第2のタイプであるDRAM(ダイナミックRAM)は、MOSキャパシタをベースにしている。キャパシタを充放電することで、セルに「1」または「0」を記憶させることができる。しかし、このキャパシタの電荷は徐々に漏れていくため、定期的にリフレッシュする必要がある。このリフレッシュ・プロセスのため、DRAMはより多くの電力を消費する。しかし、DRAMはより高い記憶密度を達成できる。

一方、ほとんどの不揮発性メモリ(non-volatile memory、NVM)は、浮遊ゲートMOSFETメモリセルアーキテクチャに基づいている。EPROM、EEPROM、フラッシュ・メモリなどの不揮発性メモリー技術は、フローティング・ゲートMOSFETトランジスターを中心とした浮遊ゲートMOSFETメモリセルを使用している。

メモリーセルの重要性

[編集]

メモリーセルを持たない論理回路は組み合わせ回路と呼ばれ、出力は現在の入力のみに依存する。しかし、メモリはデジタル・システムの重要な要素である。コンピューターでは、プログラムとデータの両方を記憶することができ、メモリセルは、デジタル・システムで後で使用するために、組み合わせ回路の出力を一時的に記憶するためにも使用される。メモリセルを使用する論理回路は順序回路と呼ばれ、出力は現在の入力だけでなく、過去の入力の履歴にも依存する。このように過去の入力履歴に依存することで、これらの回路はステートフルとなり、この状態を記憶するのがメモリ・セルである。これらの回路の動作には、タイミング・ジェネレーターまたはクロックが必要である[3]。

レイアウトがSRAMよりはるかに小さいため、より高密度に詰め込むことができ、大容量で安価なメモリが得られる。DRAMのメモリセルは、その値をキャパシタの電荷として記憶しており、電流リークの問題があるため、その値は常に書き換えられなければならない。これが、常に値が利用可能な大容量のSRAM(スタティックRAM)セルに比べて、DRAMセルの速度を遅くしている理由の一つである。これが、最近のマイクロプロセッサ・チップに含まれるオンチップ・キャッシュにSRAMメモリが使用される理由である[4]。

メモリーセルの歴史

[編集]

1946年12月11日、フレディ・ウィリアムズは、128個の40ビット・ワードを持つブラウン管(CRT)記憶装置(ウィリアムズ管)の特許を申請した。1947年に実用化され、ランダムアクセスメモリ(RAM)の最初の実用的な実装と見なされている[5]。同年、フレデリック・ヴィーエ(Frederick Viehe)によって、磁気コアメモリの最初の特許が出願された[6][7]。実用的な磁気コアメモリは、1948年にアン・ワングによって開発され、1950年代初頭にジェイ・フォレスターとヤン・A・ラジマン(Jan A. Rajchman)によって改良され、1953年にホワールウィンド・コンピュータで実用化された[8]。ケン・オルセンも開発に貢献した[9]。

半導体メモリは、1960年代初頭にバイポーラ・トランジスタでできたバイポーラ・メモリ・セルから始まった。性能は向上したものの、磁気コア・メモリの低価格化には太刀打ちできなかった[10]。

MOS memory cells

[編集]

The invention of the MOSFET (metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistor), also known as the MOS transistor, by Mohamed M. Atalla and Dawon Kahng at Bell Labs in 1959,[11] enabled the practical use of metal–oxide–semiconductor (MOS) transistors as memory cell storage elements, a function previously served by magnetic cores.[12] The first modern memory cells were introduced in 1964, when John Schmidt designed the first 64-bit p-channel MOS (PMOS) static random-access memory (SRAM).[13][14]

SRAM typically has six-transistor cells, whereas DRAM (dynamic random-access memory) typically has single-transistor cells.[15][13] In 1965, Toshiba's Toscal BC-1411 electronic calculator used a form of capacitive bipolar DRAM, storing 180-bit data on discrete memory cells, consisting of germanium bipolar transistors and capacitors.[16][17] MOS technology is the basis for modern DRAM. In 1966, Robert H. Dennard at the IBM Thomas J. Watson Research Center was working on MOS memory. While examining the characteristics of MOS technology, he found it was capable of building capacitors, and that storing a charge or no charge on the MOS capacitor could represent the 1 and 0 of a bit, while the MOS transistor could control writing the charge to the capacitor. This led to his development of a single-transistor DRAM memory cell.[18] In 1967, Dennard filed a patent for a single-transistor DRAM memory cell, based on MOS technology.[19]

The first commercial bipolar 64-bit SRAM was released by Intel in 1969 with the 3101 Schottky TTL. One year later, it released the first DRAM integrated circuit chip, the Intel 1103, based on MOS technology. By 1972, it beat previous records in semiconductor memory sales.[20] DRAM chips during the early 1970s had three-transistor cells, before single-transistor cells became standard since the mid-1970s.[15][13]

CMOS memory was commercialized by RCA, which launched a 288-bit CMOS SRAM memory chip in 1968.[21] CMOS memory was initially slower than NMOS memory, which was more widely used by computers in the 1970s.[22] In 1978, Hitachi introduced the twin-well CMOS process, with its HM6147 (4 kb SRAM) memory chip, manufactured with a 3 µm process. The HM6147 chip was able to match the performance of the fastest NMOS memory chip at the time, while the HM6147 also consumed significantly less power. With comparable performance and much less power consumption, the twin-well CMOS process eventually overtook NMOS as the most common semiconductor manufacturing process for computer memory in the 1980s.[22]

The two most common types of DRAM memory cells since the 1980s have been trench-capacitor cells and stacked-capacitor cells.[23] Trench-capacitor cells are where holes (trenches) are made in a silicon substrate, whose side walls are used as a memory cell, whereas stacked-capacitor cells are the earliest form of three-dimensional memory (3D memory), where memory cells are stacked vertically in a three-dimensional cell structure.[24] Both debuted in 1984, when Hitachi introduced trench-capacitor memory and Fujitsu introduced stacked-capacitor memory.[23]

Floating-gate MOS memory cells

[編集]The floating-gate MOSFET (FGMOS) was invented by Dawon Kahng and Simon Sze at Bell Labs in 1967.[25] They proposed the concept of floating-gate memory cells, using FGMOS transistors, which could be used to produce reprogrammable ROM (read-only memory).[26] Floating-gate memory cells later became the basis for non-volatile memory (NVM) technologies including EPROM (erasable programmable ROM), EEPROM (electrically erasable programmable ROM) and flash memory.[27]

Flash memory was invented by Fujio Masuoka at Toshiba in 1980.[28][29] Masuoka and his colleagues presented the invention of NOR flash in 1984,[30] and then NAND flash in 1987.[31] Multi-level cell (MLC) flash memory was introduced by NEC, which demonstrated quad-level cells in a 64 Mb flash chip storing 2-bit per cell in 1996.[23] 3D V-NAND, where flash memory cells are stacked vertically using 3D charge trap flash (CTP) technology, was first announced by Toshiba in 2007,[32] and first commercially manufactured by Samsung Electronics in 2013.[33][34]

Implementation

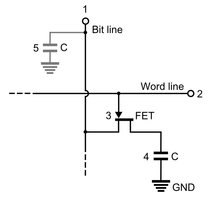

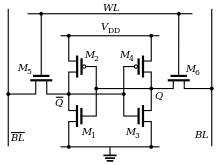

[編集]The following schematics detail the three most used implementations for memory cells:

- The dynamic random access memory cell (DRAM);

- The static random access memory cell (SRAM);

- Flip-flops like the J/K shown below, using only logic gates.

|

|

|

Operation

[編集]DRAM memory cell

[編集]

Storage

[編集]- The storage element of the DRAM memory cell is the capacitor labeled (4) in the diagram above. The charge stored in the capacitor degrades over time, so its value must be refreshed (read and rewritten) periodically. The nMOS transistor (3) acts as a gate to allow reading or writing when open or storing when closed.[35]

Reading

[編集]- For reading the Word line (2) drives a logic 1 (voltage high) into the gate of the nMOS transistor (3) which makes it conductive and the charge stored at the capacitor (4) is then transferred to the bit line (1). The bit line will have a parasitic capacitance (5) that will drain part of the charge and slow the reading process. The capacitance of the bit line will determine the needed size of the storage capacitor (4). It is a trade-off. If the storage capacitor is too small, the voltage of the bit line would take too much time to raise or not even rise above the threshold needed by the amplifiers at the end of the bit line. Since the reading process degrades the charge in the storage capacitor (4) its value is rewritten after each read.[36]

Writing

[編集]- The writing process is the easiest, the desired value logic 1 (high voltage) or logic 0 (low voltage) is driven into the bit line. The word line activates the nMOS transistor (3) connecting it to the storage capacitor (4). The only issue is to keep it open enough time to ensure that the capacitor is fully charged or discharged before turning off the nMOS transistor (3).[36]

SRAM memory cell

[編集]

(A) S = 1, R = 0: set

(B) S = 0, R = 0: hold

(C) S = 0, R = 1: reset

(D) S = 1, R = 1: not allowed

Transitioning from the restricted combination (D) to (A) leads to an unstable state.

Storage

[編集]- The working principle of SRAM memory cell can be easier to understand if the transistors M1 through M4 are drawn as logic gates. That way it is clear that at its heart, the cell storage is built by using two cross-coupled inverters. This simple loop creates a bi-stable circuit. A logic 1 at the input of the first inverter turns into a 0 at its output, and it is fed into the second inverter which transforms that logic 0 back to a logic 1 feeding back the same value to the input of the first inverter. That creates a stable state that does not change over time. Similarly the other stable state of the circuit is to have a logic 0 at the input of the first inverter. After been inverted twice it will also feedback the same value.[37]

- Therefore there are only two stable states that the circuit can be in:

- = 0 and = 1

- = 1 and = 0

Reading

[編集]- To read the contents of the memory cell stored in the loop, the transistors M5 and M6 must be turned on. when they receive voltage to their gates from the word line (), they become conductive and so the and values get transmitted to the bit line () and to its complement ().[37] Finally this values get amplified at the end of the bit lines.[37]

Writing

[編集]- The writing process is similar, the difference is that now the new value that will be stored in the memory cell is driven into the bit line () and the inverted one into its complement (). Next transistors M5 and M6 are open by driving a logic 1 (voltage high) into the word line (). This effectively connects the bit lines to the by-stable inverter loop. There are two possible cases:

- If the value of the loop is the same as the new value driven, there is no change;

- if the value of the loop is different from the new value driven there are two conflicting values, in order for the voltage in the bit lines to overwrite the output of the inverters, the size of the M5 and M6 transistors must be larger than that of the M1-M4 transistors. This allows more current to flow through first ones and therefore tips the voltage in the direction of the new value, at some point the loop will then amplify this intermediate value to full rail.[37]

Flip-flop

[編集]The flip-flop has many different implementations, its storage element is usually a latch consisting of a NAND gate loop or a NOR gate loop with additional gates used to implement clocking. Its value is always available for reading as an output. The value remains stored until it is changed through the set or reset process. Flip-flops are typically implemented using MOSFETs.

Floating gate

[編集]

Floating-gate memory cells, based on floating-gate MOSFETs, are used for most non-volatile memory (NVM) technologies, including EPROM, EEPROM and flash memory.[27] According to R. Bez and A. Pirovano:

A floating-gate memory cell is basically an MOS transistor with a gate completely surrounded by dielectrics (Fig. 1.2), the floating-gate (FG), and electrically governed by a capacitive-coupled control-gate (CG). Being electrically isolated, the FG acts as the storing electrode for the cell device. Charge injected into the FG is maintained there, allowing modulation of the ‘apparent’ threshold voltage (i.e. VT seen from the CG) of the cell transistor.[27]

See also

[編集]脚注・参考文献

[編集]- ^ D. Tang, Denny; Lee, Yuan-Jen (2010). Magnetic memory: Fundamentals and technology. Cambridge University Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-1139484497 13 December 2015閲覧。

- ^ Fletcher, William (1980). An engineering approach to digital design. Prentice-Hall. p. 283. ISBN 0-13-277699-5

- ^ Microelectronic circuits (Second ed.). Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc.. (1987). p. 883. ISBN 0-03-007328-6

- ^ “The technical question: the cache, how does it work?” (フランス語). PC World Fr. 30 March 2014時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2024年9月3日閲覧。

- ^ O’Regan, Gerard (2013). Giants of computing: A compendium of select, pivotal pioneers. Springer. p. 267. ISBN 978-1447153405 13 December 2015閲覧。

- ^ Reilly, Edwin D. (2003). Milestones in computer science and information technology. Greenwood publishing group. p. 164. ISBN 9781573565219

- ^ W. Pugh, Emerson; R. Johnson, Lyle; H. Palmer, John (1991). IBM's 360 and early 370 systems. MIT Press. p. 706. ISBN 0262161230 9 December 2015閲覧。

- ^ “1953: Whirlwind computer debuts core memory”. Computer History Museum. 2 August 2019閲覧。

- ^ Taylor, Alan (18 June 1979). Computerworld: Mass. Town has become computer capital. IDG Enterprise. pp. 25

- ^ “1966: Semiconductor RAMs serve high-speed storage needs”. Computer History Museum. 19 June 2019閲覧。

- ^ “1960 - Metal oxide semiconductor (MOS) transistor demonstrated”. The Silicon Engine (Computer history museum).

- ^ “Transistors - an overview”. ScienceDirect. 8 August 2019閲覧。

- ^ a b c “1970: Semiconductors compete with magnetic cores”. Computer history museum. 19 June 2019閲覧。 引用エラー: 無効な

<ref>タグ; name "computerhistory1970"が異なる内容で複数回定義されています - ^ Solid state design - vol. 6. Horizon house. (1965)

- ^ a b “Late 1960s: Beginnings of MOS memory”. Semiconductor history museum of Japan (23 January 2019). 27 June 2019閲覧。 引用エラー: 無効な

<ref>タグ; name "shmj-mos"が異なる内容で複数回定義されています - ^ “Spec sheet for Toshiba "TOSCAL" BC-1411”. Old calculator web museum. 3 July 2017時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。8 May 2018閲覧。

- ^ “Toshiba "Toscal" BC-1411 desktop calculator”. 20 May 2007時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2024年9月3日閲覧。

- ^ “DRAM”. IBM100. IBM (9 August 2017). 20 September 2019閲覧。

- ^ “Robert Dennard”. Encyclopædia Britannica. 8 July 2019閲覧。

- ^ Kent, Allen; Williams, James G. (6 January 1992). Encyclopedia of microcomputers: volume 9 - Icon programming language to knowledge-based systems: APL techniques. CRC press. pp. 131. ISBN 9780824727086

- ^ “1963: Complementary MOS circuit configuration is invented”. Computer history museum. 6 July 2019閲覧。

- ^ a b “1978: Double-well fast CMOS SRAM (Hitachi)”. Semiconductor history museum of Japan. 5 July 2019時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。5 July 2019閲覧。

- ^ a b c “Memory”. Semiconductor technology online (STOL). 25 June 2019閲覧。 引用エラー: 無効な

<ref>タグ; name "stol"が異なる内容で複数回定義されています - ^ “1980s: DRAM capacity increases, the shift to CMOS advances, and Japan dominates the market”. Semiconductor history museum of Japan. 19 July 2019閲覧。

- ^ Kahng, D.; Sze, S.M. (1967). “A floating-gate and its application to memory devices”. The Bell System Technical Journal 46 (6): 1288–95. doi:10.1002/j.1538-7305.1967.tb01738.x.

- ^ “1971: Reusable semiconductor ROM introduced”. Computer history museum. 19 June 2019閲覧。

- ^ a b c Bez, R.; Pirovano, A. (2019). Advances in non-volatile memory and storage technology. Woodhead Publishing. ISBN 9780081025857 引用エラー: 無効な

<ref>タグ; name "Bez"が異なる内容で複数回定義されています - ^ Fulford (24 June 2002). “Unsung hero”. Forbes. 3 March 2008時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。18 March 2008閲覧。

- ^ US 4531203 Fujio Masuoka

- ^ “Toshiba: Inventor of flash memory”. Toshiba. 20 June 2019時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。20 June 2019閲覧。

- ^ Masuoka, F.; Momodomi, M.; Iwata, Y.; Shirota, R. (1987). "New ultra high density EPROM and flash EEPROM with NAND structure cell". Electron Devices Meeting, 1987 International. IEDM 1987. IEEE. doi:10.1109/IEDM.1987.191485。

- ^ “Toshiba announces new "3D" NAND flash technology”. Engadget. (12 June 2007) 10 July 2019閲覧。

- ^ “Samsung introduces world's first 3D V-NAND based SSD for enterprise applications”. Samsung semiconductor global website. 15 April 2021時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2024年9月3日閲覧。

- ^ Clarke (2013年). “Samsung confirms 24 layers in 3D NAND”. EE Times. 2024年9月3日閲覧。

- ^ Jacob, Bruce; Ng, Spencer; Wang, David (28 July 2010). Memory systems: Cache, DRAM, disk. Morgan Kaufmann. pp. 355. ISBN 9780080553849

- ^ a b Siddiqi, Muzaffer A. (19 December 2012). Dynamic RAM: Technology advancements. CRC Press. pp. 10. ISBN 9781439893739 引用エラー: 無効な

<ref>タグ; name ":0"が異なる内容で複数回定義されています - ^ a b c d Li, Hai; Chen, Yiran (19 April 2016). Nonvolatile memory design: Magnetic, resistive, and phase change. CRC press. pp. 6, 7. ISBN 9781439807460 引用エラー: 無効な

<ref>タグ; name ":1"が異なる内容で複数回定義されています

[[Category:電子工学]] [[Category:デジタルシステム]] [[Category:デジタルエレクトロニクス]] [[Category:主記憶装置]] [[Category:未査読の翻訳があるページ]]