RAD21

RAD21は、ヒトではRAD21遺伝子にコードされるタンパク質である[5][6]。RAD21(別名: Mcd1, Scc1, KIAA0078, NXP1, HR21)は必須遺伝子であり、出芽酵母からヒトまで全ての真核生物に進化的に保存されたDNA二本鎖切断修復タンパク質をコードする。RAD21タンパク質はコヒーシンの構造的構成要素であり、コヒーシンは姉妹染色分体間の接着(cohesion)に関与する高度に保存された複合体である。

発見

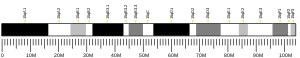

[編集]rad21遺伝子は1992年に分裂酵母Schizosaccharomyces pombeのrad21-45変異体の放射線感受性に対する相補性実験から初めてクローニングされ[7]、その後マウスやヒトでもホモログがクローニングされた[8]。ヒトのRAD21遺伝子は8番染色体の長腕8q24.11に位置する[8][9]。1997年、RAD21は染色体上のコヒーシン複合体の主要な構成要素であることが発見され[10][11]、中期から後期への移行時にシステインプロテアーゼであるセパラーゼによる切断されることで姉妹染色分体の分離、そして染色体分離が引き起こされる[12]。

構造

[編集]RAD21は、α-Kleisinと呼ばれるスーパーファミリーに属する[13]核内リン酸化タンパク質である。そのサイズはニホンヤモリGekko japonicusの278アミノ酸からシャチOrcinus orcaの746アミノ酸まで幅があるが、ヒトを含む大部分の脊椎動物では長さの中央値は631アミノ酸である。RAD21タンパク質はN末端とC末端が最も保存されており、それぞれSMC3、SMC1と結合する。RAD21中央部のSTAGドメインはSCC3(SA1/SA2)に結合し、この領域も保存されている。また、核局在シグナルやacidic-basic stretch、acidic stretchと呼ばれる領域も存在し、こうした配列の存在はクロマチンに結合する役割と符合している。RAD21は、有糸分裂時のセパラーゼ[12][14][15]やカルシウム依存性システインエンドペプチダーゼカルパイン1[16]、アポトーシスの際のカスパーゼ[17][18]など、いくつかのプロテアーゼによる切断を受ける。

相互作用

[編集]RAD21はV字型のSMC1-SMC3ヘテロ二量体と結合して三者からなるリング状構造を形成し[20]、その後SCC3(SA1/SA2)をリクルートする。この四者複合体がコヒーシン複合体と呼ばれる。現在、姉妹染色分体の接着機構には主に2つの競合するモデルが存在する。1つはone-ring embrace model[21]などと呼ばれ、もう1つはdimeric handcuff model[22][23]などと呼ばれるものである。One-ring embrace modelは、2つの姉妹染色分体が1つのコヒーシンリング内に共にトラップされることを仮定しているのに対し、handcuff modelは各染色分体が個別にトラップされることを提唱している。Handcuff modelでは、各リングは1組のRAD21、SMC1、SMC3分子から構成される。SA1もしくはSA2によって2分子のRAD21が逆平行方向に結合することで、handcuff構造が確立されるとされている[22]。

RAD21のN末端ドメインには2本のαヘリックスが存在し、SMC3のコイルドコイルと3ヘリックスバンドルを形成する[20]。RAD21の中央領域は大部分が構造をとらないと考えられているが、SA1またはSA2の結合部位[27]、セパラーゼやカスパーゼの認識モチーフ、カルパインの切断モチーフ[12][16][17][18]、PDS5A、PDS5B、NIPBLの競合的結合領域[28][29][30]など、コヒーシンの調節因子の結合部位がいくつか含まれている。RAD21のC末端ドメインはwinged helixを形成し、SMC1のヘッドドメインの2本のβシートに結合する[31]。

WAPLはSMC3-RAD21相互作用面を開いてDNAからコヒーシンを解放し、DNAのコヒーシンリングの通過を可能にする[32]。この相互作用面の開放は、SMCサブユニットへのATP結合によって調節されている。ATPの結合によってヘッドドメインは二量体化してSMC3のコイルドコイルが変形し、コイルドコイルに対するRAD21の結合が妨げられる[33]。

RAD21との相互作用因子として合計で285種類の因子が報告されており、これらは有糸分裂、アポトーシスの調節、染色体ダイナミクス、染色体接着、複製、転写調節、RNAプロセシング、DNA損傷応答、タンパク質の修飾と分解、細胞骨格や運動性など多岐にわたる細胞過程で機能するものである[34]。

機能

[編集]

RAD21は、多様な細胞機能において複数の生理的役割を果たしている。RAD21はコヒーシン複合体のサブユニットとして、S期におけるDNA複製から有糸分裂時の染色体分離まで、姉妹染色分体の接着に関与している。この機能は進化的に保存されており、適切な染色体分離、染色体構造、複製後のDNA修復、反復領域間での不適切な組換えの防止に必要不可欠である[14][26]。また、RAD21は有糸分裂時の紡錘体極の組み立てや[35]、アポトーシスの進行にも関与している可能性がある[17][18]。間期においては、コヒーシンはゲノム内の多数の部位に結合することで遺伝子発現の制御に機能している可能性がある。RAD21はコヒーシン複合体の構造的構成要素として、クロマチンと関連した機能にも寄与している。そうした機能には、DNA複製[36][37][38][39][40]、DNA損傷応答[41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49]、そして最も重要なものとして転写調節が含まれている[50][51][52][53][54][55][56][57]。近年の多くの機能研究やゲノム研究により、染色体上のコヒーシンタンパク質が造血系遺伝子の発現の重要な調節因子であることが示唆されている[58][59][60][61][62]。

RAD21はコヒーシン複合体の一部として、次のような遺伝子調節機能を果たす[63]。

- CTCFとの相互作用によるアレル特異的転写[50][51][52][56][64][65]

- 組織特異的転写因子との相互作用による組織特異的転写[52][66][67][68][69][70]

- 基本転写装置とのコミュニケーションによる一般的な転写進行[53][69][71][72]

- 多能性因子(Oct4、Nanog、Sox4、KLF2)とのCTCF非依存的な共局在

RAD21はCTCF[73]や組織特異的転写因子、基本転写装置と協働して転写を動的に調節する[74]。また適切に転写を活性化するために、クロマチンのループ構造を形成して2つの離れた領域を近接させる[65][70]。また、コヒーシンは転写抑制を保証するための転写インスレーターとしても機能する。転写を促進するエンハンサーや転写を遮断するインスレーターは染色体上の保存された調節エレメント(conserved regulatory element:CRE)に位置し、コヒーシンは遺伝子プロモーターと離れた位置にあるCREを物理的に連結することで、細胞種特異的な転写調節を行っていると考えられている[75]。

減数分裂時には、REC8が発現してコヒーシン複合体中のRAD21に置き換わる。REC8を含むコヒーシンは相同染色体間や姉妹染色分体間の接着を形成し、この接着は哺乳類の卵母細胞の場合には何年もの間持続する[76][77]。RAD21LもRAD21のパラログであり、減数分裂期の染色体分離に関与している[78]。RAD21Lを含むコヒーシン複合体の主要な役割は相同染色体間のペアリングとシナプシスであり、姉妹染色分体の接着ではない。一方、REC8は姉妹染色分体の接着に機能している可能性が高い。パキテン期の終盤にはRAD21Lの消失と共にRAD21が染色体上に出現し、そしてジプロテン期以降には大部分が解離する[78][79]。こうした第一分裂前期終盤に一過的に出現するRAD21による接着の機能は不明である。

生殖細胞系列でのRAD21のヘテロ接合型もしくはホモ接合型のミスセンス変異はコルネリア・デランゲ症候群[80][81][82][83][84][85][86][87][88][89][90] やMungan症候群[91][92]といった遺伝疾患と関係しており、こうした疾患は総称してコヒーシノパチー(cohesinopathy)と呼ばれている。RAD21の体細胞変異や増幅はヒトの固形腫瘍と造血系腫瘍の双方で広く報告されている[58][59][75][93][94][95][96][97][98][99][100][101][102][103][104][105][106][107][108][109][110][111][112][113]。

出典

[編集]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000164754 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000022314 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ Human PubMed Reference:

- ^ Mouse PubMed Reference:

- ^ “Sequence conservation of the rad21 Schizosaccharomyces pombe DNA double-strand break repair gene in human and mouse”. Genomics 36 (2): 305–15. (Jan 1997). doi:10.1006/geno.1996.0466. hdl:1765/3107. PMID 8812457.

- ^ “Entrez Gene: RAD21 RAD21 homolog (S. pombe)”. 2023年9月30日閲覧。

- ^ “Cloning and characterization of rad21 an essential gene of Schizosaccharomyces pombe involved in DNA double-strand-break repair”. Nucleic Acids Research 20 (24): 6605–11. (December 1992). doi:10.1093/nar/20.24.6605. PMC 334577. PMID 1480481.

- ^ a b “Sequence conservation of the rad21 Schizosaccharomyces pombe DNA double-strand break repair gene in human and mouse”. Genomics 36 (2): 305–15. (September 1996). doi:10.1006/geno.1996.0466. hdl:1765/3107. PMID 8812457.

- ^ “Prediction of the coding sequences of unidentified human genes. II. The coding sequences of 40 new genes (KIAA0041-KIAA0080) deduced by analysis of cDNA clones from human cell line KG-1”. DNA Research 1 (5): 223–9. (1994-01-01). doi:10.1093/dnares/1.5.223. PMID 7584044.

- ^ “A direct link between sister chromatid cohesion and chromosome condensation revealed through the analysis of MCD1 in S. cerevisiae”. Cell 91 (1): 47–57. (October 1997). doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(01)80008-8. PMC 2670185. PMID 9335334.

- ^ “Cohesins: chromosomal proteins that prevent premature separation of sister chromatids”. Cell 91 (1): 35–45. (October 1997). doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(01)80007-6. PMID 9335333.

- ^ a b c “Sister-chromatid separation at anaphase onset is promoted by cleavage of the cohesin subunit Scc1”. Nature 400 (6739): 37–42. (July 1999). Bibcode: 1999Natur.400...37U. doi:10.1038/21831. PMID 10403247.

- ^ “The structure and function of SMC and kleisin complexes”. Annual Review of Biochemistry 74 (1): 595–648. (June 2005). doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133219. PMID 15952899.

- ^ a b “Cohesin cleavage by separase required for anaphase and cytokinesis in human cells”. Science 293 (5533): 1320–3. (August 2001). Bibcode: 2001Sci...293.1320H. doi:10.1126/science.1061376. PMID 11509732.

- ^ “Cleavage of cohesin by the CD clan protease separin triggers anaphase in yeast”. Cell 103 (3): 375–86. (October 2000). doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00130-6. PMID 11081625.

- ^ a b “Calpain-1 cleaves Rad21 to promote sister chromatid separation”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 31 (21): 4335–47. (November 2011). doi:10.1128/MCB.06075-11. PMC 3209327. PMID 21876002.

- ^ a b c “Caspase proteolysis of the cohesin component RAD21 promotes apoptosis”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 277 (19): 16775–81. (May 2002). doi:10.1074/jbc.M201322200. PMID 11875078.

- ^ a b c “Linking sister chromatid cohesion and apoptosis: role of Rad21”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 22 (23): 8267–77. (December 2002). doi:10.1128/MCB.22.23.8267-8277.2002. PMC 134054. PMID 12417729.

- ^ “Systematic identification of cell cycle-dependent yeast nucleocytoplasmic shuttling proteins by prediction of composite motifs”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106 (25): 10171–6. (June 2009). Bibcode: 2009PNAS..10610171K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0900604106. PMC 2695404. PMID 19520826.

- ^ a b “Closing the cohesin ring: structure and function of its Smc3-kleisin interface”. Science 346 (6212): 963–7. (November 2014). Bibcode: 2014Sci...346..963G. doi:10.1126/science.1256917. PMC 4300515. PMID 25414305.

- ^ “Molecular architecture of SMC proteins and the yeast cohesin complex”. Molecular Cell 9 (4): 773–88. (April 2002). doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00515-4. PMID 11983169.

- ^ a b “A handcuff model for the cohesin complex”. The Journal of Cell Biology 183 (6): 1019–31. (December 2008). doi:10.1083/jcb.200801157. PMC 2600748. PMID 19075111.

- ^ “Handcuff for sisters: a new model for sister chromatid cohesion”. Cell Cycle 8 (3): 399–402. (February 2009). doi:10.4161/cc.8.3.7586. PMC 2689371. PMID 19177018.

- ^ “Sororin is a master regulator of sister chromatid cohesion and separation”. Cell Cycle 11 (11): 2073–83. (June 2012). doi:10.4161/cc.20241. PMC 3368859. PMID 22580470.

- ^ “Sororin mediates sister chromatid cohesion by antagonizing Wapl”. Cell 143 (5): 737–49. (November 2010). doi:10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.031. PMID 21111234.

- ^ a b “Road to cancer via cohesin deregulation.”. Oncology: Theory & Practice. iConcept Press Hong Kong. (2014). pp. 213–240

- ^ “Structure of cohesin subcomplex pinpoints direct shugoshin-Wapl antagonism in centromeric cohesion”. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 21 (10): 864–70. (October 2014). doi:10.1038/nsmb.2880. PMC 4190070. PMID 25173175.

- ^ “Scc2 Is a Potent Activator of Cohesin's ATPase that Promotes Loading by Binding Scc1 without Pds5”. Molecular Cell 70 (6): 1134–1148.e7. (June 2018). doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2018.05.022. PMC 6028919. PMID 29932904.

- ^ “Crystal structure of the cohesin loader Scc2 and insight into cohesinopathy”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113 (44): 12444–12449. (November 2016). doi:10.1073/pnas.1611333113. PMC 5098657. PMID 27791135.

- ^ “Structure of the Pds5-Scc1 Complex and Implications for Cohesin Function”. Cell Reports 14 (9): 2116–2126. (March 2016). doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2016.01.078. PMID 26923589.

- ^ “Structure and stability of cohesin's Smc1-kleisin interaction”. Molecular Cell 15 (6): 951–64. (September 2004). doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2004.08.030. PMID 15383284.

- ^ “Releasing Activity Disengages Cohesin's Smc3/Scc1 Interface in a Process Blocked by Acetylation”. Molecular Cell 61 (4): 563–574. (February 2016). doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2016.01.026. PMC 4769318. PMID 26895425.

- ^ “The structure of the cohesin ATPase elucidates the mechanism of SMC-kleisin ring opening”. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 27 (3): 233–239. (March 2020). doi:10.1038/s41594-020-0379-7. PMC 7100847. PMID 32066964.

- ^ a b “A cohesin-RAD21 interactome”. The Biochemical Journal 442 (3): 661–70. (March 2012). doi:10.1042/BJ20111745. PMID 22145905.

- ^ “A potential role for human cohesin in mitotic spindle aster assembly”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 276 (50): 47575–82. (December 2001). doi:10.1074/jbc.M103364200. PMID 11590136.

- ^ “Cohesin organizes chromatin loops at DNA replication factories”. Genes & Development 24 (24): 2812–22. (December 2010). doi:10.1101/gad.608210. PMC 3003199. PMID 21159821.

- ^ “Recruitment of Xenopus Scc2 and cohesin to chromatin requires the pre-replication complex”. Nature Cell Biology 6 (10): 991–6. (October 2004). doi:10.1038/ncb1177. PMID 15448702.

- ^ “Direct interaction between cohesin complex and DNA replication machinery”. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 341 (3): 770–5. (March 2006). doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.01.029. PMID 16438930.

- ^ “Cohesin acetylation speeds the replication fork”. Nature 462 (7270): 231–4. (November 2009). Bibcode: 2009Natur.462..231T. doi:10.1038/nature08550. PMC 2777716. PMID 19907496.

- ^ “Drosophila ORC localizes to open chromatin and marks sites of cohesin complex loading”. Genome Research 20 (2): 201–11. (February 2010). doi:10.1101/gr.097873.109. PMC 2813476. PMID 19996087.

- ^ “DNA double-strand breaks trigger genome-wide sister-chromatid cohesion through Eco1 (Ctf7)”. Science 317 (5835): 245–8. (July 2007). Bibcode: 2007Sci...317..245U. doi:10.1126/science.1140637. PMID 17626885.

- ^ “Distinct targets of the Eco1 acetyltransferase modulate cohesion in S phase and in response to DNA damage”. Molecular Cell 34 (3): 311–21. (May 2009). doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2009.04.008. PMC 2737744. PMID 19450529.

- ^ “Postreplicative recruitment of cohesin to double-strand breaks is required for DNA repair”. Molecular Cell 16 (6): 1003–15. (December 2004). doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.026. PMID 15610742.

- ^ “Genome-wide reinforcement of cohesin binding at pre-existing cohesin sites in response to ionizing radiation in human cells”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 285 (30): 22784–92. (July 2010). doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.134577. PMC 2906269. PMID 20501661.

- ^ “The cohesin complex is required for the DNA damage-induced G2/M checkpoint in mammalian cells”. The EMBO Journal 28 (17): 2625–35. (September 2009). doi:10.1038/emboj.2009.202. PMC 2738698. PMID 19629043.

- ^ “Double-strand breaks arising by replication through a nick are repaired by cohesin-dependent sister-chromatid exchange”. EMBO Reports 7 (9): 919–26. (September 2006). doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400774. PMC 1559660. PMID 16888651.

- ^ “Cohesin and DNA damage repair”. Experimental Cell Research 312 (14): 2687–93. (August 2006). doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.06.024. PMID 16876157.

- ^ “Damage-induced reactivation of cohesin in postreplicative DNA repair”. BioEssays 30 (1): 5–9. (January 2008). doi:10.1002/bies.20691. PMC 4127326. PMID 18081005.

- ^ “S-phase and DNA damage activated establishment of sister chromatid cohesion--importance for DNA repair”. Experimental Cell Research 316 (9): 1445–53. (May 2010). doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.12.018. PMID 20043905.

- ^ a b “Cohesin mediates transcriptional insulation by CCCTC-binding factor”. Nature 451 (7180): 796–801. (February 2008). Bibcode: 2008Natur.451..796W. doi:10.1038/nature06634. PMID 18235444.

- ^ a b “Cohesins coordinate gene transcriptions of related function within Saccharomyces cerevisiae”. Cell Cycle 9 (8): 1601–6. (April 2010). doi:10.4161/cc.9.8.11307. PMC 3096706. PMID 20404480.

- ^ a b c “A CTCF-independent role for cohesin in tissue-specific transcription”. Genome Research 20 (5): 578–88. (May 2010). doi:10.1101/gr.100479.109. PMC 2860160. PMID 20219941.

- ^ a b “Mediator and cohesin connect gene expression and chromatin architecture”. Nature 467 (7314): 430–5. (September 2010). Bibcode: 2010Natur.467..430K. doi:10.1038/nature09380. PMC 2953795. PMID 20720539.

- ^ “A direct role for cohesin in gene regulation and ecdysone response in Drosophila salivary glands”. Current Biology 20 (20): 1787–98. (October 2010). doi:10.1016/j.cub.2010.09.006. PMC 4763543. PMID 20933422.

- ^ “Gene regulation: the cohesin ring connects developmental highways”. Current Biology 20 (20): R886-8. (October 2010). doi:10.1016/j.cub.2010.09.036. PMID 20971431.

- ^ a b “Cohesins functionally associate with CTCF on mammalian chromosome arms”. Cell 132 (3): 422–33. (February 2008). doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.011. PMID 18237772.

- ^ “Transcriptional dysregulation in NIPBL and cohesin mutant human cells”. PLOS Biology 7 (5): e1000119. (May 2009). doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000119. PMC 2680332. PMID 19468298.

- ^ a b “Leukemia-Associated Cohesin Mutants Dominantly Enforce Stem Cell Programs and Impair Human Hematopoietic Progenitor Differentiation”. Cell Stem Cell 17 (6): 675–688. (December 2015). doi:10.1016/j.stem.2015.09.017. PMC 4671831. PMID 26607380.

- ^ a b “Cohesin loss alters adult hematopoietic stem cell homeostasis, leading to myeloproliferative neoplasms”. The Journal of Experimental Medicine 212 (11): 1833–50. (October 2015). doi:10.1084/jem.20151323. PMC 4612095. PMID 26438359.

- ^ “Dose-dependent role of the cohesin complex in normal and malignant hematopoiesis”. The Journal of Experimental Medicine 212 (11): 1819–32. (October 2015). doi:10.1084/jem.20151317. PMC 4612085. PMID 26438361.

- ^ “Cohesin Mutations in Myeloid Malignancies”. Trends in Cancer 3 (4): 282–293. (April 2017). doi:10.1016/j.trecan.2017.02.006. PMC 5472227. PMID 28626802.

- ^ “Closing the loop on cohesin in hematopoiesis”. Blood 134 (24): 2123–2125. (December 2019). doi:10.1182/blood.2019003279. PMC 6908834. PMID 31830276.

- ^ Cheng, Haizi; Zhang, Nenggang; Pati, Debananda (2020-10-20). “Cohesin subunit RAD21: From biology to disease”. Gene 758: 144966. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2020.144966. ISSN 1879-0038. PMC 7949736. PMID 32687945.

- ^ “CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF) and cohesin influence the genomic architecture of the Igh locus and antisense transcription in pro-B cells”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108 (23): 9566–71. (June 2011). Bibcode: 2011PNAS..108.9566D. doi:10.1073/pnas.1019391108. PMC 3111298. PMID 21606361.

- ^ a b “CTCF/cohesin-mediated DNA looping is required for protocadherin α promoter choice”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109 (51): 21081–6. (December 2012). Bibcode: 2012PNAS..10921081G. doi:10.1073/pnas.1219280110. PMC 3529044. PMID 23204437.

- ^ “Cohesins form chromosomal cis-interactions at the developmentally regulated IFNG locus”. Nature 460 (7253): 410–3. (July 2009). Bibcode: 2009Natur.460..410H. doi:10.1038/nature08079. PMC 2869028. PMID 19458616.

- ^ “Cohesin regulates tissue-specific expression by stabilizing highly occupied cis-regulatory modules”. Genome Research 22 (11): 2163–75. (November 2012). doi:10.1101/gr.136507.111. PMC 3483546. PMID 22780989.

- ^ “A role for cohesin in T-cell-receptor rearrangement and thymocyte differentiation”. Nature 476 (7361): 467–71. (August 2011). Bibcode: 2011Natur.476..467S. doi:10.1038/nature10312. PMC 3179485. PMID 21832993.

- ^ a b “Transcription factor binding in human cells occurs in dense clusters formed around cohesin anchor sites”. Cell 154 (4): 801–13. (August 2013). doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.034. PMID 23953112.

- ^ a b “Intrachromosomal looping is required for activation of endogenous pluripotency genes during reprogramming”. Cell Stem Cell 13 (1): 30–5. (July 2013). doi:10.1016/j.stem.2013.05.012. PMID 23747202.

- ^ “Cohesin selectively binds and regulates genes with paused RNA polymerase”. Current Biology 21 (19): 1624–34. (October 2011). doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.08.036. PMC 3193539. PMID 21962715.

- ^ “Genome-wide control of RNA polymerase II activity by cohesin”. PLOS Genetics 9 (3): e1003382. (March 2013). doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003382. PMC 3605059. PMID 23555293.

- ^ “CTCF physically links cohesin to chromatin”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105 (24): 8309–14. (June 2008). Bibcode: 2008PNAS..105.8309R. doi:10.1073/pnas.0801273105. PMC 2448833. PMID 18550811.

- ^ “Cohesin at active genes: a unifying theme for cohesin and gene expression from model organisms to humans”. Current Opinion in Cell Biology 25 (3): 327–33. (June 2013). doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2013.02.003. PMC 3691354. PMID 23465542.

- ^ a b “Cohesin mutations in myeloid malignancies: underlying mechanisms”. Experimental Hematology & Oncology 3 (1): 13. (2014). doi:10.1186/2162-3619-3-13. PMC 4046106. PMID 24904756.

- ^ “Rec8-containing cohesin maintains bivalents without turnover during the growing phase of mouse oocytes”. Genes & Development 24 (22): 2505–16. (November 2010). doi:10.1101/gad.605910. PMC 2975927. PMID 20971813.

- ^ “Disjunction of homologous chromosomes in meiosis I depends on proteolytic cleavage of the meiotic cohesin Rec8 by separin”. Cell 103 (3): 387–98. (October 2000). doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00131-8. PMID 11081626.

- ^ a b “RAD21L, a novel cohesin subunit implicated in linking homologous chromosomes in mammalian meiosis”. The Journal of Cell Biology 192 (2): 263–76. (January 2011). doi:10.1083/jcb.201008005. PMC 3172173. PMID 21242291.

- ^ “A new meiosis-specific cohesin complex implicated in the cohesin code for homologous pairing”. EMBO Reports 12 (3): 267–75. (March 2011). doi:10.1038/embor.2011.2. PMC 3059921. PMID 21274006.

- ^ “Delineation of phenotypes and genotypes related to cohesin structural protein RAD21”. Human Genetics 139 (5): 575–592. (May 2020). doi:10.1007/s00439-020-02138-2. PMC 7170815. PMID 32193685.

- ^ “RAD21 mutations cause a human cohesinopathy”. American Journal of Human Genetics 90 (6): 1014–27. (June 2012). doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.04.019. PMC 3370273. PMID 22633399.

- ^ “Genetic heterogeneity in Cornelia de Lange syndrome (CdLS) and CdLS-like phenotypes with observed and predicted levels of mosaicism”. Journal of Medical Genetics 51 (10): 659–68. (October 2014). doi:10.1136/jmedgenet-2014-102573. PMC 4173748. PMID 25125236.

- ^ “Two novel RAD21 mutations in patients with mild Cornelia de Lange syndrome-like presentation and report of the first familial case”. Gene 537 (2): 279–84. (March 2014). doi:10.1016/j.gene.2013.12.045. PMID 24378232.

- ^ “A novel RAD21 variant associated with intrafamilial phenotypic variation in Cornelia de Lange syndrome - review of the literature”. Clinical Genetics 91 (4): 647–649. (April 2017). doi:10.1111/cge.12863. PMID 27882533.

- ^ “High diagnostic yield of syndromic intellectual disability by targeted next-generation sequencing”. Journal of Medical Genetics 54 (2): 87–92. (February 2017). doi:10.1136/jmedgenet-2016-103964. PMID 27620904.

- ^ “A novel RAD21 mutation in a boy with mild Cornelia de Lange presentation: Further delineation of the phenotype”. European Journal of Medical Genetics 63 (1): 103620. (January 2020). doi:10.1016/j.ejmg.2019.01.010. PMID 30716475.

- ^ “A novel RAD21 p.(Gln592del) variant expands the clinical description of Cornelia de Lange syndrome type 4 - Review of the literature”. European Journal of Medical Genetics 62 (6): 103526. (June 2019). doi:10.1016/j.ejmg.2018.08.007. hdl:10641/1986. PMID 30125677.

- ^ “Cornelia de Lange syndrome caused by heterozygous deletions of chromosome 8q24: comments on the article by Pereza et al. [2012]”. American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part A 167 (6): 1426–7. (June 2015). doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.36974. PMID 25899858.

- ^ “Multiple exostoses, mental retardation, hypertrichosis, and brain abnormalities in a boy with a de novo 8q24 submicroscopic interstitial deletion”. American Journal of Medical Genetics 113 (4): 326–32. (December 2002). doi:10.1002/ajmg.10845. PMID 12457403.

- ^ “Further case of microdeletion of 8q24 with phenotype overlapping Langer-Giedion without TRPS1 deletion”. American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part A 146A (12): 1587–92. (June 2008). doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.32347. PMID 18478595.

- ^ “Mutations in RAD21 disrupt regulation of APOB in patients with chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction”. Gastroenterology 148 (4): 771–782.e11. (April 2015). doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2014.12.034. hdl:11693/23636. PMC 4375026. PMID 25575569.

- ^ “Familial visceral myopathy with pseudo-obstruction, megaduodenum, Barrett's esophagus, and cardiac abnormalities”. The American Journal of Gastroenterology 98 (11): 2556–60. (November 2003). doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.08707.x. PMID 14638363.

- ^ “Emerging strategies to target the dysfunctional cohesin complex in cancer”. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets 23 (6): 525–537. (June 2019). doi:10.1080/14728222.2019.1609943. PMID 31020869.

- ^ “Gene expression profiling predicts clinical outcome of breast cancer”. Nature 415 (6871): 530–6. (January 2002). doi:10.1038/415530a. hdl:1874/15552. PMID 11823860.

- ^ “Enhanced RAD21 cohesin expression confers poor prognosis and resistance to chemotherapy in high grade luminal, basal and HER2 breast cancers”. Breast Cancer Research 13 (1): R9. (January 2011). doi:10.1186/bcr2814. PMC 3109576. PMID 21255398.

- ^ “Correlation of invasion and metastasis of cancer cells, and expression of the RAD21 gene in oral squamous cell carcinoma”. Virchows Archiv 448 (4): 435–41. (April 2006). doi:10.1007/s00428-005-0132-y. PMID 16416296.

- ^ “RAD21 cohesin overexpression is a prognostic and predictive marker exacerbating poor prognosis in KRAS mutant colorectal carcinomas”. British Journal of Cancer 110 (6): 1606–13. (March 2014). doi:10.1038/bjc.2014.31. PMC 3960611. PMID 24548858.

- ^ “RAD21 and KIAA0196 at 8q24 are amplified and overexpressed in prostate cancer”. Genes, Chromosomes & Cancer 39 (1): 1–10. (January 2004). doi:10.1002/gcc.10289. PMID 14603436.

- ^ “Reduced cohesin destabilizes high-level gene amplification by disrupting pre-replication complex bindings in human cancers with chromosomal instability”. Nucleic Acids Research 44 (2): 558–72. (January 2016). doi:10.1093/nar/gkv933. PMC 4737181. PMID 26420833.

- ^ “The cohesin subunit Rad21 is a negative regulator of hematopoietic self-renewal through epigenetic repression of Hoxa7 and Hoxa9”. Leukemia 31 (3): 712–719. (March 2017). doi:10.1038/leu.2016.240. PMC 5332284. PMID 27554164.

- ^ “Cohesin gene mutations in tumorigenesis: from discovery to clinical significance”. BMB Reports 47 (6): 299–310. (June 2014). doi:10.5483/BMBRep.2014.47.6.092. PMC 4163871. PMID 24856830.

- ^ “Genetic alterations of the cohesin complex genes in myeloid malignancies”. Blood 124 (11): 1790–8. (September 2014). doi:10.1182/blood-2014-04-567057. PMC 4162108. PMID 25006131.

- ^ “Cohesin mutations in human cancer”. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer 1866 (1): 1–11. (August 2016). doi:10.1016/j.bbcan.2016.05.002. PMC 4980180. PMID 27207471.

- ^ “Preleukemic mutations in human acute myeloid leukemia affect epigenetic regulators and persist in remission”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 111 (7): 2548–53. (February 2014). Bibcode: 2014PNAS..111.2548C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1324297111. PMC 3932921. PMID 24550281.

- ^ “Genomic and epigenomic landscapes of adult de novo acute myeloid leukemia”. The New England Journal of Medicine 368 (22): 2059–74. (May 2013). doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1301689. PMC 3767041. PMID 23634996.

- ^ “Recurrent mutations in multiple components of the cohesin complex in myeloid neoplasms”. Nature Genetics 45 (10): 1232–7. (October 2013). doi:10.1038/ng.2731. PMID 23955599.

- ^ “Mutations in the cohesin complex in acute myeloid leukemia: clinical and prognostic implications”. Blood 123 (6): 914–20. (February 2014). doi:10.1182/blood-2013-07-518746. PMID 24335498.

- ^ “Acute myeloid leukemia ontogeny is defined by distinct somatic mutations”. Blood 125 (9): 1367–76. (February 2015). doi:10.1182/blood-2014-11-610543. PMC 4342352. PMID 25550361.

- ^ “Prognostic impacts and dynamic changes of cohesin complex gene mutations in de novo acute myeloid leukemia”. Blood Cancer Journal 7 (12): 663. (December 2017). doi:10.1038/s41408-017-0022-y. PMC 5802563. PMID 29288251.

- ^ “Mutation patterns identify adult patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia aged 60 years or older who respond favorably to standard chemotherapy: an analysis of Alliance studies”. Leukemia 32 (6): 1338–1348. (June 2018). doi:10.1038/s41375-018-0068-2. PMC 5992022. PMID 29563537.

- ^ “de novo acute myeloid leukemia without 2016 WHO Classification-defined cytogenetic abnormalities”. Haematologica 103 (4): 626–633. (April 2018). doi:10.3324/haematol.2017.181842. PMC 5865424. PMID 29326119.

- ^ “Comprehensive mutational profiling of core binding factor acute myeloid leukemia”. Blood 127 (20): 2451–9. (May 2016). doi:10.1182/blood-2015-12-688705. PMC 5457131. PMID 26980726.

- ^ “The landscape of somatic mutations in Down syndrome-related myeloid disorders”. Nature Genetics 45 (11): 1293–9. (November 2013). doi:10.1038/ng.2759. PMID 24056718.