「ストロンチウム」の版間の差分

| (24人の利用者による、間の32版が非表示) | |||

| 85行目: | 85行目: | ||

== 名称 == |

== 名称 == |

||

ストロンチ |

元素名は、[[1787年]]に発見されたストロンチアン石(ストロンチウムを含む鉱物)の産出地、[[スコットランド]]の{{仮リンク|ストロンチアン|en|Strontian|label=}}({{lang-en|Strontian}}、{{lang-gd|Sron an t-Sìthein}})という村にちなむ。<ref name="str">{{Cite |和書 |author =[[桜井弘]]|||title = 元素111の新知識|date = 1998| pages = 195|publisher =[[講談社]]| series = |isbn=4-06-257192-7 |ref = harv }}</ref>。 |

||

元素名は、[[1787年]]に発見されたストロンチアン石(ストロンチウムを含む鉱物)の産出地、[[スコットランド]]のストロンチアン (strontian) に由来する<ref name="str">{{Cite |和書 |author =[[桜井弘]]|||title = 元素111の新知識|date = 1998| pages = 195|publisher =[[講談社]]| series = |isbn=4-06-257192-7 |ref = harv }}</ref>。 |

|||

== 性質 == |

== 性質 == |

||

[[ファイル:Strontium 1.jpg|thumb|left|酸化ストロンチウムの[[デンドライト]]]] |

[[ファイル:Strontium 1.jpg|thumb|left|酸化ストロンチウムの[[デンドライト]]]] |

||

常温、常圧で安定な |

結晶構造は温度、圧力条件により異なる3種類を取り得る。常温、常圧で安定なものは[[面心立方格子構造]] (FCC, α-Sr)、213℃〜621℃の間では六方最密充填構造(HCP,β-Sr)、621℃〜769℃の間では体心立方格子(BCC,γ-Sc)がそれぞれ最も安定となる。銀白色の[[金属]]で、比重は2.63、[[融点]]は777 {{℃}}、[[沸点]]は1382 {{℃}}。[[炎色反応]]で赤色を呈する。空気中では灰白色の[[酸化物]]被膜を生じる。[[水]]とは激しく反応し[[水酸化ストロンチウム]]と[[水素]]を生成する。 |

||

: <chem>Sr + 2 H2O -> Sr(OH)2 + H2</chem> |

: <chem>Sr + 2 H2O -> Sr(OH)2 + H2</chem> |

||

生理的には[[カルシウム]]に良く似た挙動を示し、[[骨格]]に含まれる。 |

生理的には[[カルシウム]]に良く似た挙動を示し、[[骨格]]に含まれる。 |

||

| 107行目: | 105行目: | ||

== 同位体 == |

== 同位体 == |

||

{{Main|ストロンチウムの同位体|ストロンチウム90}} |

{{Main|ストロンチウムの同位体|ストロンチウム90}} |

||

[[ウラン]]の[[核分裂反応|核分裂]]生成物など、人工的に作られる代表的な物質[[放射性同位体]]として[[ヨウ素131]]、[[セシウム137]]と共にストロンチウム90 (<sup>90</sup>Sr) がある。ストロンチウム90は、[[半減期]]が28.8年で[[ベータ崩壊]]を起こして、[[イットリウム|イットリウム90]]に変わる。[[原子力電池]]の放射線エネルギー源として使われる。体内に入ると電子配置・半径が似ているため、骨の中の[[カルシウム]]と置き換わって体内に蓄積し長期間にわたって放射線を出し続ける。このため大変危険であるが、揮発性化合物を作りにくく<ref name="Sr90"/>[[原発事故]]で放出される量はセシウム137と比較すると少ない。 |

[[ウラン]]の[[核分裂反応|核分裂]]生成物など、人工的に作られる代表的な物質[[放射性同位体]]として[[ヨウ素131]]、[[セシウム137]]と共にストロンチウム90 (<sup>90</sup>Sr) がある。ストロンチウム90は、[[半減期]]が28.8年で[[ベータ崩壊]]を起こして、[[イットリウム|イットリウム90]]に変わる。[[原子力電池]]の放射線エネルギー源として使われる。体内に入ると電子配置・半径が似ているため、骨の中の[[カルシウム]]と置き換わって体内に蓄積し長期間にわたって放射線を出し続ける。このため大変危険であるが、揮発性化合物を作りにくく<ref name="Sr90"/>[[原子力事故|原発事故]]で放出される量はセシウム137と比較すると少ない。 |

||

[[地質学]]においては、[[ルビジウム|ルビジウム87]]から[[ベータ崩壊|β崩壊]]により[[半減期]]4.9×10<sup>10</sup>年でストロンチウム87が生成されることを利用して、主に数千万年以前の岩石の年代測定に用いられる。([[Rb-Sr法]])<ref>{{Cite journal|author=柴田 賢|year=1985|title=Rb-Sr法|journal=地学雑誌|volume=94-7|page=102-106}}</ref> |

|||

骨に吸収されやすいという性質を生かして、別の放射性同位体であるストロンチウム89は[[骨腫瘍]]の治療に用いられる。ストロンチウム89の半減期は50.52日と短く比較的短期間で崩壊するため、短期間に強力な放射線を患部に直接照射させることができる。 |

骨に吸収されやすいという性質を生かして、別の放射性同位体であるストロンチウム89は[[骨腫瘍]]の治療に用いられる。ストロンチウム89の半減期は50.52日と短く比較的短期間で崩壊するため、短期間に強力な放射線を患部に直接照射させることができる。 |

||

骨に吸収されやすいので自然界で見つかるのとほぼ同じ比率で、4つ全ての安定同位体が取り込まれている。また、同位体の分布比率は地理的な場所によって異なる傾向がある。<ref name="PriceSchoeninger1985">{{cite journal|last1=Price|first1=T. Douglas|last2=Schoeninger|first2=Margaret J.|author2-link=Margaret Schoeninger|last3=Armelagos|first3=George J.|title=Bone chemistry and past behavior: an overview|journal=Journal of Human Evolution|volume=14|issue=5|year=1985|pages=419–47|doi=10.1016/S0047-2484(85)80022-1}}</ref><ref name="SteadmanBrudevold1958">{{cite journal|last1=Steadman|first1=Luville T.|last2=Brudevold|first2=Finn|last3=Smith|first3=Frank A.|title=Distribution of strontium in teeth from different geographic areas|journal=The Journal of the American Dental Association|volume=57|issue=3|year=1958|pages=340–44|doi=10.14219/jada.archive.1958.0161|pmid=13575071}}</ref> これによって古代における人間の移動や、戦場の埋葬地に混在する人間の起源を特定することに役立つ。 |

|||

<ref name="SchweissingGrupe2003">{{cite journal|last1=Schweissing|first1=Matthew Mike|last2=Grupe|first2=Gisela|title=Stable strontium isotopes in human teeth and bone: a key to migration events of the late Roman period in Bavaria|journal=Journal of Archaeological Science|volume=30|issue=11|year=2003|pages=1373–83|doi=10.1016/S0305-4403(03)00025-6}}</ref> |

|||

=== 生体に対する影響 === |

=== 生体に対する影響 === |

||

| 121行目: | 124行目: | ||

== 歴史 == |

== 歴史 == |

||

[[Image:FlammenfärbungSr.png|thumb|left|upright=0.6|ストロンチウムの炎色試験]] |

|||

単体金属は[[1808年]]、[[イギリス|英国]]の[[ハンフリー・デービー]]により、[[電解法]]を用いて単離される<ref name="str" />。 |

|||

1790年、バリウムの調合に携わった医師である[[Adair Crawford]]と同僚の[[William Cruickshank (chemist)|William Cruickshank]]がストロンチアン石が他の重晶石("heavy spars")の元となる石の特性とは異なる特性を示すことを認識した<ref>{{cite journal | first = Adair | last = Crawford | date= 1790 | title = On the medicinal properties of the muriated barytes | journal = Medical Communications| volume = 2 | pages = 301–59 | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=bHI_AAAAcAAJ&pg=P301}}</ref>。これによりAdairは355ページで「・・・実際にこのスコットランドの鉱物はこれまで十分に調べられていない新種の土類である可能性が高い」と締めくくっている。医師で鉱物収集家である[[Friedrich Gabriel Sulzer]]は[[ヨハン・フリードリヒ・ブルーメンバッハ]]とともにストロンチアン産の鉱物を分析しストロンチアナイトと名付けた。また、{{仮リンク|毒重石|en|witherite}}とは異なり新たな土類(neue Grunderde)を含んでいるという結論を出した<ref>{{cite journal | url =https://books.google.com/books?id=gCY7AAAAcAAJ&pg=PA433 | journal =Bergmännisches Journal | title = Über den Strontianit, ein Schottisches Foßil, das ebenfalls eine neue Grunderde zu enthalten scheint| last1 =Sulzer| first1 =Friedrich Gabriel | first2 = Johann Friedrich | last2 = Blumenbach| date =1791 | pages = 433–36}}</ref>。1793年、グラスゴー大学の化学教授Thomas Charles Hopeがストロンタイト(''strontites'')という名前を提案する<ref>Although Thomas C. Hope had investigated strontium ores since 1791, his research was published in: {{cite journal | first =Thomas Charles | last =Hope | date = 1798 | title = Account of a mineral from Strontian and of a particular species of earth which it contains | journal = Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh| volume = 4 | issue = 2 | pages =3–39| url = https://books.google.com/books?id=5TEeAQAAMAAJ&pg=RA1-PA3 | doi =10.1017/S0080456800030726}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Murray, T. |date=1993| title= Elementary Scots: The Discovery of Strontium |journal = Scottish Medical Journal| volume = 38 |pages = 188–89 |pmid=8146640 |issue=6 |doi=10.1177/003693309303800611}}</ref><ref>{{cite web| url = http://www.chem.ed.ac.uk/about/professors/hope.html| author = Doyle, W.P.| title = Thomas Charles Hope, MD, FRSE, FRS (1766–1844)| publisher = The University of Edinburgh| url-status = dead| archiveurl = https://web.archive.org/web/20130602122314/http://www.chem.ed.ac.uk/about/professors/hope.html| archivedate = 2 June 2013| df = dmy-all|accessdate=2020-03}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | first =Thomas Charles | last =Hope | date = 1794 | title = Account of a mineral from Strontian and of a particular species of earth which it contains | journal = Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh| volume = 3 | issue = 2 | pages =141–49| url =https://books.google.com/books?id=7StFAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA143 | doi =10.1017/S0080456800020275}}</ref><!--https://books.google.com/books?id=3GQ7AQAAIAAJ&pg=PA134-->。1808年に[[ハンフリー・デービー]]卿により、[[塩化ストロンチウム]]と[[酸化水銀(II)]]を含む混合物の[[電気分解]]により最終的に分離され、1808年6月30日の王立協会での講演で発表された<ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Davy | first1 = H. | date = 1808 | title = Electro-chemical researches on the decomposition of the earths; with observations on the metals obtained from the alkaline earths, and on the amalgam procured from ammonia | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=gpwEAAAAYAAJ&pg=102#v=onepage&q&f=false | journal = Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London | volume = 98 | pages = 333–70 | doi=10.1098/rstl.1808.0023}}</ref>。他のアルカリ土類の名前に合わせ、名前をストロンチウムに変更した<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.lochaber-news.co.uk/news/fullstory.php/aid/2644/Strontian_gets_set_for_anniversary.html|author=Taylor, Stuart|title=Strontian gets set for anniversary|publisher=Lochaber News|date=19 June 2008|url-status=bot: unknown|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20090113005443/http://www.lochaber-news.co.uk/news/fullstory.php/aid/2644/Strontian_gets_set_for_anniversary.html|archivedate=13 January 2009|df=dmy-all|accessdate=2020-03}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author = Weeks, Mary Elvira |authorlink=Mary Elvira Weeks|title = The discovery of the elements: X. The alkaline earth metals and magnesium and cadmium |journal = Journal of Chemical Education |date = 1932 |volume = 9 |pages = 1046–57 |doi = 10.1021/ed009p1046 |issue = 6 |bibcode = 1932JChEd...9.1046W }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.1080/00033794200201411 |title = The early history of strontium |date = 1942 |last1 = Partington |first1 = J. R. |journal = Annals of Science |volume = 5 |page = 157 |issue = 2}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | doi = 10.1080/00033795100202211 | title = The early history of strontium. Part II | date = 1951 | last1 = Partington | first1 = J. R. | journal = Annals of Science | volume = 7 | page = 95}}</ref><!-- The google book https://books.google.com/books?id=LagWAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA139 could help with original literature--><ref>Many other early investigators examined strontium ore, among them: '''(1)''' Martin Heinrich Klaproth, "Chemische Versuche über die Strontianerde" (Chemical experiments on strontian ore), ''Crell's Annalen'' (September 1793) no. ii, pp. 189–202 ; and "Nachtrag zu den Versuchen über die Strontianerde" (Addition to the Experiments on Strontian Ore), ''Crell's Annalen'' (February 1794) no. i, p. 99 ; also '''(2)''' {{cite journal | last1 = Kirwan | first1 = Richard | date = 1794 | title = Experiments on a new earth found near Stronthian in Scotland | journal = The Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy | volume = 5 | pages = 243–56 }}</ref>。 |

|||

ストロンチウムの最初の大規模な適用は、[[テンサイ]]からの砂糖の生産であった。水酸化ストロンチウムを用いた結晶化プロセスは1849年に[[Augustin-Pierre Dubrunfaut]]により特許がとられたが<ref name="Metalle in der Elektrochemie">{{cite book | url = https://books.google.com/?id=xDkoAQAAIAAJ&q=dubrunfaut+strontium&dq=dubrunfaut+strontium| title =Metalle in der Elektrochemie | pages = 158–62 | author1 = Fachgruppe Geschichte Der Chemie, Gesellschaft Deutscher Chemiker | date = 2005}}</ref>、1870年代初期にプロセスが改善されたことで大規模な導入が行われた。ドイツの[[砂糖工業]]は20世紀までこのプロセスをうまく利用していた。[[第一次世界大戦]]前、テンサイの砂糖産業はこのプロセスに年間10万から15万トンの水酸化ストロンチウムを使用していた<ref name="books.google.de">{{cite book | chapter = strontium saccharate process | chapter-url = https://books.google.com/books?id=-vd_cn4K8NUC&pg=PA341 | isbn = 978-1-4437-2504-0 | title = Manufacture of Sugar from the Cane and Beet | author1 = Heriot, T. H. P | date = 2008}}</ref>。水酸化ストロンチウムはこのプロセスでリサイクルされたが、製造中の損失を補う需要は[[ミュンスター行政管区|ミュンスターランド]]でストロンチアナイトの採掘を始める大きな需要を生み出すほど高かった。ドイツのストロンチアナイトの採掘は[[グロスタシャー]]で[[天青石]]鉱床の採掘が始まると終了した<ref>{{cite web | url = http://www.lwl.org/LWL/Kultur/Westfalen_Regional/Wirtschaft/Bergbau/Strontianitbergbau/ | title = Der Strontianitbergbau im Münsterland | first = Martin | last = Börnchen | accessdate = 9 November 2010 | url-status = dead | archiveurl = https://web.archive.org/web/20141211085517/http://www.lwl.org/LWL/Kultur/Westfalen_Regional/Wirtschaft/Bergbau/Strontianitbergbau/ | archivedate = 11 December 2014 | df = dmy-all }}</ref>。これらの鉱山は1884年から1941年までの世界のストロンチウム供給のほとんどを賄った。グラナダ盆地の天青石鉱床はしばらくの間知られていたが、大規模な採掘は1950年代より前には始まっていない<ref>{{cite journal | doi = 10.1016/0037-0738(84)90055-1 | title = Genesis and evolution of strontium deposits of the granada basin (Southeastern Spain): Evidence of diagenetic replacement of a stromatolite belt | date = 1984 | last1 = Martin | first1 = Josèm | last2 = Ortega-Huertas | first2 = Miguel | last3 = Torres-Ruiz | first3 = Jose | journal = Sedimentary Geology | volume = 39 | issue = 3–4 | page = 281|bibcode = 1984SedG...39..281M }}</ref>。 |

|||

[[大気圏内核実験]]による[[核分裂生成物]]の中に、ストロンチウム90が比較的多いことが観察された。カルシウムとの化学的動態の類似性からストロンチウム90が骨に蓄積する可能性が考えられ、ストロンチウムの代謝に関する研究が重要なトピックとなった<ref>{{cite web | url = http://www-nds.iaea.org/sgnucdat/c1.htm | publisher = iaea.org| title = Chain Fission Yields |accessdate=2020-03}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | pmc = 1985251 | date = 1968 | last1 = Nordin | first1 = B. E. | title = Strontium Comes of Age | volume = 1 | issue = 5591 | page = 566 | journal = British Medical Journal | doi = 10.1136/bmj.1.5591.566}}</ref>。 |

|||

==産出== |

|||

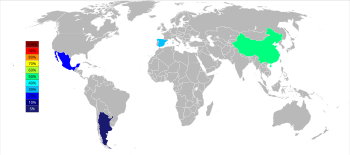

[[File:World Strontium Production 2014.svg|upright=1.6|thumb|2014年のストロンチウムの生産国<ref name="usgs15">{{cite web |publisher = United States Geological Survey |accessdate = 26 March 2016 |title = Mineral Commodity Summaries 2015: Strontium |first = Joyce A. |last = Ober |url = http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/strontium/mcs-2015-stron.pdf }}</ref>|alt=Grey and white world map with China colored green representing 50%, Spain colored blue-green representing 30%, Mexico colored light blue representing 20%, Argentina colored dark blue representing below 5% of strontium world production.]] |

|||

2015年現在の天青石としてのストロンチウムの3つの主要産出国は、中国(150,000 [[トン|t]])、スペイン(90,000 t)、メキシコ(70,000 t)であり、アルゼンチン(10,000 t)やモロッコ(2,500 t)は小規模産出国である。ストロンチウム鉱床はアメリカに広く存在しているが、1959年以降採掘されていない<ref name="usgs15"/>。 |

|||

採掘される天青石(SrSO<sub>4</sub>)の大部分は2つのプロセスにより炭酸塩に変換される。天青石を炭酸ナトリウム溶液で直接浸出するか、石炭で焙煎し硫化物を作る。2番目の段階では主に[[硫化ストロンチウム]]を含む暗色の物質が作られる。このいわゆる「黒灰」(ブラックアッシュ)は水に溶けて濾過される。炭酸ストロンチウムは[[二酸化炭素]]を入れることにより硫化ストロンチウム溶液から沈殿する<ref>{{cite book | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=5smDPzkw0wEC&pg=PA401 | title = Production of SrCO<sub>3</sub> by black ash process: Determination of reductive roasting parameters| page = 401 | isbn = 978-90-5410-829-0 | last1 = Kemal | first1 = Mevlüt | last2 = Arslan | first2 = V. | last3 = Akar | first3 = A. | last4 = Canbazoglu | first4 = M. | date = 1996}}</ref>。硫酸塩は炭素還元により[[硫化物]]に還元される。 |

|||

:SrSO<sub>4</sub> + 2 C → SrS + 2 CO<sub>2</sub> |

|||

毎年30万トンにこのプロセスが行われている<ref name=Ullmann>MacMillan, J. Paul; Park, Jai Won; Gerstenberg, Rolf; Wagner, Heinz; Köhler, Karl and Wallbrecht, Peter (2002) "Strontium and Strontium Compounds" in ''Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry'', Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. {{DOI|10.1002/14356007.a25_321}}.</ref>。 |

|||

ストロンチウム金属は、商業的には酸化ストロンチウムを[[アルミニウム]]で還元することにより製造されている。混合物から[[蒸留]]される<ref name=Ullmann/>。溶融[[塩化カリウム]]中の[[塩化ストロンチウム]]溶液の[[電気分解]]により小規模で調製することもできる<ref name=Greenwood111>Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 111</ref>。 |

|||

:Sr<sup>2+</sup> + 2 e<sup>-</sup> → Sr |

|||

:2 Cl<sup>−</sup> → Cl<sub>2</sub> + 2 e<sup>-</sup> |

|||

== ストロンチウムの化合物 == |

== ストロンチウムの化合物 == |

||

* [[酸化ストロンチウム]] ( |

* [[酸化ストロンチウム]] ({{chem|Sr|O}}) - [[塩基性酸化物]] |

||

* [[水酸化ストロンチウム]] (Sr( |

* [[水酸化ストロンチウム]] ({{chem|Sr|(|O|H|)|2}}) - [[強塩基]] |

||

* [[チタン酸ストロンチウム]] ( |

* [[チタン酸ストロンチウム]] ({{chem|Sr|Ti|O|3}}) - [[常誘電体]] |

||

* [[クロム酸ストロンチウム]] ( |

* [[クロム酸ストロンチウム]] ({{chem|Sr|Cr|O|4}}) - [[黄色]][[顔料]]・[[ストロンチウムクロメート]](ストロンチウムイエロー、ストロンシャンイエロー)の主成分。 |

||

* [[ストロンチアン石]] ( |

* [[ストロンチアン石]] ({{chem|Sr|C|O|3}}) - 主成分[[炭酸ストロンチウム]] |

||

* [[天青石]] ( |

* [[天青石]] ({{chem|Sr|S|O|4}}) - 主成分[[硫酸ストロンチウム]] |

||

* [[硝酸ストロンチウム]] (Sr( |

* [[硝酸ストロンチウム]] ({{chem|Sr|(|N|O|3|)|2}}) |

||

* [[塩化ストロンチウム]] ( |

* [[塩化ストロンチウム]] ({{chem|Sr|Cl|2}}) |

||

* [[ |

* [[水素化ストロンチウム]]({{chem|Sr|H|2}}) |

||

* [[リン酸水素ストロンチウム]] ({{chem|Sr|H|P|O|4}}) - [[蛍光体]] |

|||

* [[乳酸ストロンチウム]]({{chem|C|6|H|10|O|6|Sr}}) |

|||

== 参考書籍 == |

== 参考書籍 == |

||

| 138行目: | 161行目: | ||

== 出典 == |

== 出典 == |

||

{{ |

{{脚注ヘルプ}} |

||

{{Reflist|2}} |

|||

== 関連項目 == |

== 関連項目 == |

||

{{Commons|Strontium}} |

{{Commons|Strontium}} |

||

* {{仮リンク|ルビジウム-ストロンチウム年代測定|en|Rubidium-strontium dating}} |

* {{仮リンク|ルビジウム-ストロンチウム年代測定|en|Rubidium-strontium dating}} |

||

* [[光格子時計]] |

|||

* [[原子時計#ストロンチウム格子時計|ストロンチウム格子時計]] |

|||

== 外部リンク == |

== 外部リンク == |

||

* {{ICSC|1534}} |

* {{ICSC|1534}} |

||

* {{Kotobank}} |

|||

{{元素周期表}} |

{{元素周期表}} |

||

{{ストロンチウムの化合物}} |

{{ストロンチウムの化合物}} |

||

{{Normdaten}} |

{{Normdaten}} |

||

{{DEFAULTSORT:すとろんちうむ}} |

{{DEFAULTSORT:すとろんちうむ}} |

||

[[Category:ストロンチウム|*]] |

[[Category:ストロンチウム|*]] |

||

[[Category:元素]] |

|||

[[Category:アルカリ土類金属]] |

|||

[[Category:第5周期元素]] |

|||

2024年12月16日 (月) 21:58時点における最新版

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 外見 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

銀白色

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 一般特性 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 名称, 記号, 番号 | ストロンチウム, Sr, 38 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 分類 | アルカリ土類金属 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 族, 周期, ブロック | 2, 5, s | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 原子量 | 87.62 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 電子配置 | [Kr] 5s2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 電子殻 | 2, 8, 18, 8, 2(画像) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 物理特性 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 相 | 固体 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 密度(室温付近) | 2.64 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 融点での液体密度 | 2.375 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 融点 | 1050 K, 777 °C, 1431 °F | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 沸点 | 1655 K, 1382 °C, 2520 °F | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 融解熱 | 7.43 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 蒸発熱 | 136.9 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 熱容量 | (25 °C) 26.4 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 蒸気圧 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 原子特性 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 酸化数 | 2, 1[1](強塩基性酸化物) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 電気陰性度 | 0.95(ポーリングの値) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| イオン化エネルギー | 第1: 549.5 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 第2: 1064.2 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 第3: 4138 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 原子半径 | 215 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 共有結合半径 | 195±10 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ファンデルワールス半径 | 249 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| その他 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 結晶構造 | 面心立方格子構造 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 磁性 | 常磁性 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 電気抵抗率 | (20 °C) 132 nΩ⋅m | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 熱伝導率 | (300 K) 35.4 W/(m⋅K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 熱膨張率 | (25 °C) 22.5 μm/(m⋅K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 剛性率 | 6.1 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ポアソン比 | 0.28 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| モース硬度 | 1.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS登録番号 | 7440-24-6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 主な同位体 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 詳細はストロンチウムの同位体を参照 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

ストロンチウム(ラテン語: strontium[2])は原子番号38の元素で、元素記号は Sr である。軟らかく銀白色のアルカリ土類金属で、化学反応性が高い。空気にさらされると、表面が黄味を帯びてくる。天然には天青石やストロンチアン石などの鉱物中に存在する。放射性同位体のストロンチウム90 (90Sr) は放射性降下物に含まれ、その半減期は28.90年である。

名称

[編集]元素名は、1787年に発見されたストロンチアン石(ストロンチウムを含む鉱物)の産出地、スコットランドのストロンチアン(英語: Strontian、スコットランド・ゲール語: Sron an t-Sìthein)という村にちなむ。[3]。

性質

[編集]

結晶構造は温度、圧力条件により異なる3種類を取り得る。常温、常圧で安定なものは面心立方格子構造 (FCC, α-Sr)、213℃〜621℃の間では六方最密充填構造(HCP,β-Sr)、621℃〜769℃の間では体心立方格子(BCC,γ-Sc)がそれぞれ最も安定となる。銀白色の金属で、比重は2.63、融点は777 °C、沸点は1382 °C。炎色反応で赤色を呈する。空気中では灰白色の酸化物被膜を生じる。水とは激しく反応し水酸化ストロンチウムと水素を生成する。

酸化ストロンチウムのアルミニウムによる還元、および塩化ストロンチウムなどの溶融塩電解により金属単体が製造され、蒸留により精製される。

用途

[編集]炎色反応が赤であるため、花火や発炎筒の炎の赤い色の発生には塩化ストロンチウムなどが用いられる。そのほか、高温超伝導体の材料として使われる。

炭酸ストロンチウムは、ブラウン管などの陰極線管のガラスに添加される。また、フェライトなどの磁性材料の原料としても用いられる。

単体のストロンチウムは酸素などとの反応性が高いため、真空装置中のガスを吸着するゲッターとして用いられる。

同位体

[編集]ウランの核分裂生成物など、人工的に作られる代表的な物質放射性同位体としてヨウ素131、セシウム137と共にストロンチウム90 (90Sr) がある。ストロンチウム90は、半減期が28.8年でベータ崩壊を起こして、イットリウム90に変わる。原子力電池の放射線エネルギー源として使われる。体内に入ると電子配置・半径が似ているため、骨の中のカルシウムと置き換わって体内に蓄積し長期間にわたって放射線を出し続ける。このため大変危険であるが、揮発性化合物を作りにくく[4]原発事故で放出される量はセシウム137と比較すると少ない。

地質学においては、ルビジウム87からβ崩壊により半減期4.9×1010年でストロンチウム87が生成されることを利用して、主に数千万年以前の岩石の年代測定に用いられる。(Rb-Sr法)[5]

骨に吸収されやすいという性質を生かして、別の放射性同位体であるストロンチウム89は骨腫瘍の治療に用いられる。ストロンチウム89の半減期は50.52日と短く比較的短期間で崩壊するため、短期間に強力な放射線を患部に直接照射させることができる。

骨に吸収されやすいので自然界で見つかるのとほぼ同じ比率で、4つ全ての安定同位体が取り込まれている。また、同位体の分布比率は地理的な場所によって異なる傾向がある。[6][7] これによって古代における人間の移動や、戦場の埋葬地に混在する人間の起源を特定することに役立つ。 [8]

生体に対する影響

[編集]ストロンチウム90は骨に蓄積されることで生物学的半減期が長くなる(長年、体内にとどまる)ため、ストロンチウム90は、ベータ線を放出する放射性物質のなかでも人体に対する危険が大きいとされている[4]。

家畜への蓄積

[編集]1957年から北海道で行われた調査では、1960年代から1970年代に北海道のウシやウマの骨に蓄積されていた放射性ストロンチウム (90Sr) は2,000-4,000 mBq/gを記録していたが、大気圏内核実験の禁止後は次第に減少し、現在では100 mBq以下程度まで減少している。また、ウシとウマではウマの方がより高濃度で蓄積をしていて加齢と蓄積量には相関関係があるとしている。屋外の牧草を直接食べるウシとウマは、放射能汚染をトレースするための良い生物指標となる[9]。

放射性ストロンチウムの体外排泄

[編集]1960年代、米ソを中心に大気圏内の核実験が盛んに行われた。これに伴い、体内に取り込まれた放射性物質の除去剤や排泄促進法に関する研究も数多く行われている。放射性ストロンチウムは生体内ではカルシウムと同じような挙動をとる。IAEA(国際原子力機関)は放射性ストロンチウムを大量に摂取した場合、アルギン酸の投与を考慮するように勧告している[10]。アルギン酸は褐藻類の細胞間を充填する粘質多糖で、カルシウムよりもストロンチウムに対する親和性が高いことが知られている。ヒトにアルギン酸を経口投与してから放射性ストロンチウムを投与すると、投与していない場合と比べて体内残留量が約1⁄8になることが報告されている[11][12]。また動物実験でも同様の効果があることが確かめられている[13]。

歴史

[編集]

1790年、バリウムの調合に携わった医師であるAdair Crawfordと同僚のWilliam Cruickshankがストロンチアン石が他の重晶石("heavy spars")の元となる石の特性とは異なる特性を示すことを認識した[14]。これによりAdairは355ページで「・・・実際にこのスコットランドの鉱物はこれまで十分に調べられていない新種の土類である可能性が高い」と締めくくっている。医師で鉱物収集家であるFriedrich Gabriel Sulzerはヨハン・フリードリヒ・ブルーメンバッハとともにストロンチアン産の鉱物を分析しストロンチアナイトと名付けた。また、毒重石とは異なり新たな土類(neue Grunderde)を含んでいるという結論を出した[15]。1793年、グラスゴー大学の化学教授Thomas Charles Hopeがストロンタイト(strontites)という名前を提案する[16][17][18][19]。1808年にハンフリー・デービー卿により、塩化ストロンチウムと酸化水銀(II)を含む混合物の電気分解により最終的に分離され、1808年6月30日の王立協会での講演で発表された[20]。他のアルカリ土類の名前に合わせ、名前をストロンチウムに変更した[21][22][23][24][25]。

ストロンチウムの最初の大規模な適用は、テンサイからの砂糖の生産であった。水酸化ストロンチウムを用いた結晶化プロセスは1849年にAugustin-Pierre Dubrunfautにより特許がとられたが[26]、1870年代初期にプロセスが改善されたことで大規模な導入が行われた。ドイツの砂糖工業は20世紀までこのプロセスをうまく利用していた。第一次世界大戦前、テンサイの砂糖産業はこのプロセスに年間10万から15万トンの水酸化ストロンチウムを使用していた[27]。水酸化ストロンチウムはこのプロセスでリサイクルされたが、製造中の損失を補う需要はミュンスターランドでストロンチアナイトの採掘を始める大きな需要を生み出すほど高かった。ドイツのストロンチアナイトの採掘はグロスタシャーで天青石鉱床の採掘が始まると終了した[28]。これらの鉱山は1884年から1941年までの世界のストロンチウム供給のほとんどを賄った。グラナダ盆地の天青石鉱床はしばらくの間知られていたが、大規模な採掘は1950年代より前には始まっていない[29]。

大気圏内核実験による核分裂生成物の中に、ストロンチウム90が比較的多いことが観察された。カルシウムとの化学的動態の類似性からストロンチウム90が骨に蓄積する可能性が考えられ、ストロンチウムの代謝に関する研究が重要なトピックとなった[30][31]。

産出

[編集]

2015年現在の天青石としてのストロンチウムの3つの主要産出国は、中国(150,000 t)、スペイン(90,000 t)、メキシコ(70,000 t)であり、アルゼンチン(10,000 t)やモロッコ(2,500 t)は小規模産出国である。ストロンチウム鉱床はアメリカに広く存在しているが、1959年以降採掘されていない[32]。

採掘される天青石(SrSO4)の大部分は2つのプロセスにより炭酸塩に変換される。天青石を炭酸ナトリウム溶液で直接浸出するか、石炭で焙煎し硫化物を作る。2番目の段階では主に硫化ストロンチウムを含む暗色の物質が作られる。このいわゆる「黒灰」(ブラックアッシュ)は水に溶けて濾過される。炭酸ストロンチウムは二酸化炭素を入れることにより硫化ストロンチウム溶液から沈殿する[33]。硫酸塩は炭素還元により硫化物に還元される。

- SrSO4 + 2 C → SrS + 2 CO2

毎年30万トンにこのプロセスが行われている[34]。

ストロンチウム金属は、商業的には酸化ストロンチウムをアルミニウムで還元することにより製造されている。混合物から蒸留される[34]。溶融塩化カリウム中の塩化ストロンチウム溶液の電気分解により小規模で調製することもできる[35]。

- Sr2+ + 2 e- → Sr

- 2 Cl− → Cl2 + 2 e-

ストロンチウムの化合物

[編集]- 酸化ストロンチウム (SrO) - 塩基性酸化物

- 水酸化ストロンチウム (Sr(OH)2) - 強塩基

- チタン酸ストロンチウム (SrTiO3) - 常誘電体

- クロム酸ストロンチウム (SrCrO4) - 黄色顔料・ストロンチウムクロメート(ストロンチウムイエロー、ストロンシャンイエロー)の主成分。

- ストロンチアン石 (SrCO3) - 主成分炭酸ストロンチウム

- 天青石 (SrSO4) - 主成分硫酸ストロンチウム

- 硝酸ストロンチウム (Sr(NO3)2)

- 塩化ストロンチウム (SrCl2)

- 水素化ストロンチウム(SrH2)

- リン酸水素ストロンチウム (SrHPO4) - 蛍光体

- 乳酸ストロンチウム(C6H10O6Sr)

参考書籍

[編集]- 『放射化学』著:古川路明 出版:朝倉書店 1994年03月25日 ISBN 978-4-254-14545-8 C3343

出典

[編集]- ^ P. Colarusso et al. (1996). “High-Resolution Infrared Emission Spectrum of Strontium Monofluoride”. J. Molecular Spectroscopy 175: 158.

- ^ WEBSTER'S DICTIONARY, 1913

- ^ 桜井弘『元素111の新知識』講談社、1998年、195頁。ISBN 4-06-257192-7。

- ^ a b ストロンチウム-90 原子力資料情報室 (CNIC)

- ^ 柴田 賢 (1985). “Rb-Sr法”. 地学雑誌 94-7: 102-106.

- ^ Price, T. Douglas; Schoeninger, Margaret J.; Armelagos, George J. (1985). “Bone chemistry and past behavior: an overview”. Journal of Human Evolution 14 (5): 419–47. doi:10.1016/S0047-2484(85)80022-1.

- ^ Steadman, Luville T.; Brudevold, Finn; Smith, Frank A. (1958). “Distribution of strontium in teeth from different geographic areas”. The Journal of the American Dental Association 57 (3): 340–44. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.1958.0161. PMID 13575071.

- ^ Schweissing, Matthew Mike; Grupe, Gisela (2003). “Stable strontium isotopes in human teeth and bone: a key to migration events of the late Roman period in Bavaria”. Journal of Archaeological Science 30 (11): 1373–83. doi:10.1016/S0305-4403(03)00025-6.

- ^ 近山之雄, 八木行雄, 塩野浩紀 ほか、「北海道における90Srの牛馬骨への蓄積状況 『RADIOISOTOPES』 1999年 48巻 4号 p.283-287、日本アイソトープ協会

- ^ IAEA Safety Series 47 (1978)

- ^ Hesp R. and Ramsbottom, B., Nature (1965)

- ^ 市川竜資「放射性ストロンチウムとアルギン酸」『化学と生物』1969年 7巻 4号 p.208-211, doi:10.1271/kagakutoseibutsu1962.7.208

- ^ 西村義一, 魏仁善, 金絖崙 ほか、「放射性Srの代謝に及ぼすキトサンとアルギン酸の影響について」『RADIOISOTOPES』 1991年 40巻 6号 p.244-247, doi:10.3769/radioisotopes.40.6_244

- ^ Crawford, Adair (1790). “On the medicinal properties of the muriated barytes”. Medical Communications 2: 301–59.

- ^ Sulzer, Friedrich Gabriel; Blumenbach, Johann Friedrich (1791). “Über den Strontianit, ein Schottisches Foßil, das ebenfalls eine neue Grunderde zu enthalten scheint”. Bergmännisches Journal: 433–36.

- ^ Although Thomas C. Hope had investigated strontium ores since 1791, his research was published in: Hope, Thomas Charles (1798). “Account of a mineral from Strontian and of a particular species of earth which it contains”. Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 4 (2): 3–39. doi:10.1017/S0080456800030726.

- ^ Murray, T. (1993). “Elementary Scots: The Discovery of Strontium”. Scottish Medical Journal 38 (6): 188–89. doi:10.1177/003693309303800611. PMID 8146640.

- ^ Doyle, W.P.. “Thomas Charles Hope, MD, FRSE, FRS (1766–1844)”. The University of Edinburgh. 2 June 2013時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2020年3月閲覧。

- ^ Hope, Thomas Charles (1794). “Account of a mineral from Strontian and of a particular species of earth which it contains”. Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 3 (2): 141–49. doi:10.1017/S0080456800020275.

- ^ Davy, H. (1808). “Electro-chemical researches on the decomposition of the earths; with observations on the metals obtained from the alkaline earths, and on the amalgam procured from ammonia”. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 98: 333–70. doi:10.1098/rstl.1808.0023.

- ^ Taylor, Stuart (19 June 2008). “Strontian gets set for anniversary”. Lochaber News. 13 January 2009時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2020年3月閲覧。

- ^ Weeks, Mary Elvira (1932). “The discovery of the elements: X. The alkaline earth metals and magnesium and cadmium”. Journal of Chemical Education 9 (6): 1046–57. Bibcode: 1932JChEd...9.1046W. doi:10.1021/ed009p1046.

- ^ Partington, J. R. (1942). “The early history of strontium”. Annals of Science 5 (2): 157. doi:10.1080/00033794200201411.

- ^ Partington, J. R. (1951). “The early history of strontium. Part II”. Annals of Science 7: 95. doi:10.1080/00033795100202211.

- ^ Many other early investigators examined strontium ore, among them: (1) Martin Heinrich Klaproth, "Chemische Versuche über die Strontianerde" (Chemical experiments on strontian ore), Crell's Annalen (September 1793) no. ii, pp. 189–202 ; and "Nachtrag zu den Versuchen über die Strontianerde" (Addition to the Experiments on Strontian Ore), Crell's Annalen (February 1794) no. i, p. 99 ; also (2) Kirwan, Richard (1794). “Experiments on a new earth found near Stronthian in Scotland”. The Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy 5: 243–56.

- ^ Fachgruppe Geschichte Der Chemie, Gesellschaft Deutscher Chemiker (2005). Metalle in der Elektrochemie. pp. 158–62

- ^ Heriot, T. H. P (2008). “strontium saccharate process”. Manufacture of Sugar from the Cane and Beet. ISBN 978-1-4437-2504-0

- ^ Börnchen, Martin. “Der Strontianitbergbau im Münsterland”. 11 December 2014時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。9 November 2010閲覧。

- ^ Martin, Josèm; Ortega-Huertas, Miguel; Torres-Ruiz, Jose (1984). “Genesis and evolution of strontium deposits of the granada basin (Southeastern Spain): Evidence of diagenetic replacement of a stromatolite belt”. Sedimentary Geology 39 (3–4): 281. Bibcode: 1984SedG...39..281M. doi:10.1016/0037-0738(84)90055-1.

- ^ “Chain Fission Yields”. iaea.org. 2020年3月閲覧。

- ^ Nordin, B. E. (1968). “Strontium Comes of Age”. British Medical Journal 1 (5591): 566. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5591.566. PMC 1985251.

- ^ a b Ober, Joyce A.. “Mineral Commodity Summaries 2015: Strontium”. United States Geological Survey. 26 March 2016閲覧。

- ^ Kemal, Mevlüt; Arslan, V.; Akar, A.; Canbazoglu, M. (1996). Production of SrCO3 by black ash process: Determination of reductive roasting parameters. p. 401. ISBN 978-90-5410-829-0

- ^ a b MacMillan, J. Paul; Park, Jai Won; Gerstenberg, Rolf; Wagner, Heinz; Köhler, Karl and Wallbrecht, Peter (2002) "Strontium and Strontium Compounds" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a25_321.

- ^ Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 111

関連項目

[編集]外部リンク

[編集]- 国際化学物質安全性カード ストロンチウム (ICSC:1534) 日本語版(国立医薬品食品衛生研究所による), 英語版

- 『ストロンチウム』 - コトバンク