利用者:加藤勝憲/第二次世界大戦時のドイツによる強制労働

Original Nazi propaganda caption: "A 14-year-old youth from Ukraine repairs damaged motor vehicles in a Berlin workshop of the German Wehrmacht. January 1945."

| |||||||||

第二次世界大戦中、ナチス・ドイツ(ドイツ語:Zwangsarbeit)とドイツ占領下のヨーロッパ全域で、奴隷労働と強制労働の利用がかつてない規模で行われた[2]。また、占領地ヨーロッパの住民の大量絶滅German economic exploitation にも貢献した。ドイツ軍はヨーロッパのほぼ20カ国からおよそ1,200万人を拉致し、その約3分の2は中欧と東欧からであった[1]。さらに多くの労働者が、戦争中、敵(連合国)の爆撃や職場への砲撃によって民間人犠牲者となった[3]。最盛期には、強制労働者はドイツの労働力の20%を占めていた。 死亡者と離職者を含めると、戦争中の一時期に約1500万人の男女が強制労働者であった[4]。

ユダヤ人以外にも、ベラルーシ、ウクライナ、ロシアの住民に最も過酷な強制送還と強制労働政策が適用された。戦争が終わるまでに、ベラルーシの人口の半分が殺されるか強制送還された[5][6]。

1945年のナチス・ドイツの敗北によって、約1100万人の外国人(「避難民」に分類される)が解放されたが、そのほとんどは強制労働者と捕虜だった。戦時中、ドイツ軍は工場での不自由な労働のために、ソ連兵捕虜に加えて650万人の民間人を帝国に連行していた。彼らを帰国させることは連合国にとって最優先事項であった。しかし、ソ連市民の場合、帰還はしばしば協力の疑いや収容所への収容を意味した。国連救援リハビリテーション局(UNRRA)、赤十字、軍事作戦は、食料、衣料、住居、帰国支援を提供した。全部で520万人の外国人労働者と捕虜がソ連に、160万人がポーランドに、150万人がフランスに、90万人がイタリアに、さらにユーゴスラビア、チェコスロバキア、オランダ、ハンガリー、ベルギーにそれぞれ30万人から40万人が送還された[7]。

The defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945 freed approximately 11 million foreigners (categorized as "displaced persons"), most of whom were forced labourers and POWs. In wartime, the German forces had brought into the Reich 6.5 million civilians in addition to Soviet POWs for unfree labour in factories.[1] Returning them home was a high priority for the Allies. However, in the case of citizens of the USSR, returning often meant suspicion of collaboration or the Gulag. The United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), Red Cross, and military operations provided food, clothing, shelter, and assistance in returning home. In all, 5.2 million foreign workers and POWs were repatriated to the Soviet Union, 1.6 million to Poland, 1.5 million to France, and 900,000 to Italy, along with 300,000 to 400,000 each to Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, the Netherlands, Hungary, and Belgium.

Forced workers

[編集]

ヒトラーのレーベンスラウム(生活の余地)政策は、オスト将軍計画として知られる東方の新しい土地の征服と、ドイツに安価な商品と労働力を提供するためのこれらの土地の搾取を強く強調していた。戦前から、ナチス・ドイツは奴隷労働者の供給を維持していた。この慣行は、ホームレス、同性愛者、犯罪者、政治的反体制者、共産主義者、ユダヤ人など、政権が邪魔にならないようにしたい者を集めた「信頼できない要素」(ドイツ語:unzuverlässige Elemente)の労働キャンプの初期から始まった。第二次世界大戦中、ナチスは収容者のカテゴリー別にいくつかの労働収容所(Arbeitslager)を運営していた。ナチスの労働収容所の囚人は、短い配給と劣悪な環境で死ぬまで働かされ、働けなくなれば殺された。ナチスのもとでの強制労働の直接的な結果として、多くの者が死亡した。

Hitler's policy of Lebensraum (room for living) strongly emphasized the conquest of new lands in the East, known as Generalplan Ost, and the exploitation of these lands to provide cheap goods and labour for Germany. Even before the war, Nazi Germany maintained a supply of slave labour. This practice started from the early days of labour camps of "unreliable elements" (ドイツ語: unzuverlässige Elemente), such as the homeless, homosexuals, criminals, political dissidents, communists, Jews, and anyone whom the regime wanted out of the way. During World War II the Nazis operated several categories of Arbeitslager (labour camps) for different categories of inmates. Prisoners in Nazi labour camps were worked to death on short rations and in bad conditions, or killed if they became unable to work. Many died as a direct result of forced labour under the Nazis.[1]

ポーランド侵攻後、12歳以上のポーランドのユダヤ人と総督府に住む12歳以上のポーランド人は強制労働の対象となった[8]。 歴史家のヤン・グロスは、ポーランド人労働者の「15パーセント以下」がドイツでの労働を志願したと推定している[9]。 1942年、総督府に住むすべての非ドイツ人は強制労働の対象となった[10]。

After the invasion of Poland, Polish Jews over the age of 12 and Poles over the age of 12 living in the General Government were subject to forced labor.[7] Historian Jan Gross estimates that “no more than 15 percent” of Polish workers volunteered to go to work in Germany.[8] In 1942, all non-Germans living in the General Government were subject to forced labor.

最も多くの労働収容所は、ドイツの戦争産業での労働力、爆撃された鉄道や橋の修理、農場での労働を提供するために、占領下で強制的に拉致された民間人を収容していた(「ワパンカ」を参照)。1930年代から1940年代にかけては、シャベルワーク、資材運搬、機械加工など、今日では機械で行われるような仕事の多くがまだ手作業で行われていたため、手作業は需要の高い資源であった。戦争が進むにつれ、奴隷労働の利用は大幅に増加した。戦争捕虜や民間人の「不届き者」が占領地から連行された。ティッセン、クルップ、IGファルベン、ボッシュ、ダイムラー・ベンツ、デマーグ、ヘンシェル、ユンカース、メッサーシュミット、シーメンス、さらにはフォルクスワーゲンなどのドイツ企業によって、何百万人ものユダヤ人、スラブ人、その他の被征服民族が奴隷労働者として使用された[11]。 [戦争が始まると、外国の子会社はナチス支配下のドイツ国家に接収され、国有化された。ナチス・ドイツ国内の戦争経済では、戦争期間中、およそ1,200万人の強制労働者(そのほとんどが東欧人)が雇用された[13]。 ドイツの奴隷労働に対するニーズは、ホイアクション(Heu-Aktion)と呼ばれる作戦で、子どもたちまでもが誘拐されて働かされるまでに高まった。

The largest number of labour camps held civilians forcibly abducted in the occupied countries (see Łapanka) to provide labour in the German war industry, repair bombed railroads and bridges, or work on farms. Manual labour was a resource in high demand, as much of the work that today would be done with machines was still a manual affair in the 1930s and 1940s – shoveling, material handling, machining, and many others. As the war progressed, the use of slave labour increased massively. Prisoners of war and civilian "undesirables" were brought in from occupied territories. Millions of Jews, Slavs and other conquered peoples were used as slave labourers by German corporations, such as Thyssen, Krupp, IG Farben, Bosch, Daimler-Benz, Demag, Henschel, Junkers, Messerschmitt, Siemens, and even Volkswagen,[9] not to mention the German subsidiaries of foreign firms, such as Fordwerke (a subsidiary of the Ford Motor Company) and Adam Opel AG (a subsidiary of General Motors) among others.[10] Once the war had begun, the foreign subsidiaries were seized and nationalized by the Nazi-controlled German state, and work conditions there deteriorated as they did throughout German industry. About 12 million forced labourers, most of whom were Eastern Europeans, were employed in the German war economy inside Nazi Germany throughout the war.[11] The German need for slave labour grew to the point that even children were kidnapped to work in an operation called the Heu-Aktion. More than 2,000 German companies profited from slave labour during the Nazi era, including Deutsche Bank and Siemens.[12]

分類

[編集]

帝国のために働くためにドイツに連れてこられたフレムダーベイター(「外国人労働者」)の間に階級制度が作られた。この階級制度は、ドイツの同盟国や中立国から来た高給労働者から、征服されたウンターメンシェン(「亜人」)集団の強制労働者まで、特権の低い労働者の階層を基礎としたものであった。

- Gastarbeitnehmer (「ゲスト労働者」) - ゲルマン諸国、スカンジナビア諸国、フランス、イタリア[13]、その他のドイツの同盟国(ルーマニア、ブルガリア、ハンガリー)、および友好的な中立国(スペインやスイスなど)からの労働者。ドイツで働く外国人労働者のうち、中立国またはドイツと同盟を結んでいた国の出身者はわずか1%程度であった[1]。

- Zwangsarbeiter(強制労働者) - ドイツと同盟関係にない国からの強制労働者。この労働者階級は次のように分類された:

- 軍事抑留者(Militärinternierte Militärinternierte )-戦争捕虜。ジュネーブ条約は、捕虜国が一定の制限の範囲内で、将校以外の捕虜に労働を強制することを認めていた。 例えば、ポーランドの非軍事捕虜のほとんど全員(約30万人)がナチス・ドイツで強制労働させられた。1944年、ドイツでは200万人近くの捕虜が強制労働者として雇用されていた[13]。他の外国人労働者と比べて、捕虜は比較的裕福であった。特に、アメリカやイギリスのようなまだ戦争状態にあった西側諸国の出身者であれば、その待遇の最低基準はジュネーブ条約によって義務付けられていたからである。 彼らの労働条件と福利は国際赤十字の監督下にあり、虐待があった場合には、(同様の強制労働を行なっていた)アメリカ、イギリス、カナダに収容されていたドイツ人捕虜への報復はほぼ確実であった。 しかし、これらの労働者の待遇は、出身国、時代、特定の職場によって大きく異なっていた。特に、ソ連の戦争捕虜は、ソ連が批准も実施もしていなかったジュネーブ条約による保護の対象とはナチスが考えていなかったため、まったく残忍な扱いを受けた。

- ツィヴィラールバイターZivilarbeiter(「民間人労働者」)-ポーランド総督府支配地区から来たポーランド民族[[13]は、厳格なポーランドの法令Polish decreesによって規制されていた:彼らははるかに低い賃金を受け、公共交通機関などの便利なものを使用することができず、多くの公共スペースやビジネスを訪問することができなかった(例えば、彼らはドイツの教会の礼拝、スイミングプール、レストランを訪問することができなかった)、彼らはより長い時間働かなければならず、より少ない食料配給が割り当てられ、彼らは外出禁止令の対象となった。ポーランド人は日常的に休日を与えられず、週7日働かなければならなかった。許可なく結婚することはできず、金銭や高価なもの(自転車、カメラ、ライターなど)を所持することはできなかった。彼らは衣服に "ポーランドP "の印をつけることを義務づけられていた。1939年には、ドイツには約30万人のポーランド人ツィヴィラールバイターがいた[15]。 1944年までに、その数は約170万人に急増し[15]、異なる説では280万人(占領下のポーランドの囚人労働力の約10%)であった[16]。 1944年には、総督府と拡大ソ連からの捕虜[15]を含め、合計で約760万人の外国人いわゆる民間人労働者がドイツで雇用され、他の国々からも同数の労働者がこのカテゴリーに属していた。 rations; they were subject to a curfew. Poles were routinely denied holidays and had to work seven days a week; they could not enter marriage between themselves without a permit; they could not possess money or objects of value: bicycles, cameras, or even lighters. They were required to wear a sign: the "Polish P", on their clothing. In 1939, there were about 300,000 Polish Zivilarbeiter in Germany.[1][13] By 1944, their number skyrocketted to about 1.7 million,[13] or 2.8 million by different accounts (approximately 10% of occupied Poland's prisoner workforce). In 1944, there were about 7.6 million foreign so-called civilian workers employed in Germany in total, including POWs from Generalgouvernement and the expanded USSR,[13] with a similar number of workers in this category from other countries.[1]

- Ostarbeiter (「東方労働者」)-主にガリツィエン地方Distrikt Galizien とウクライナ帝国軍Reichskommissariat Ukraineで検挙されたソ連人とポーランド人の市民労働者。彼らはOST(「東方」)という標識が付けられ、有刺鉄線でフェンスで囲まれた収容所で監視されながら暮らさなければならず、ゲシュタポや工場の警備員の恣意に特にさらされた。OST労働者の数は300万人から550万人と推定されている[14][15]。

一般に、西ヨーロッパの外国人労働者は、ドイツ人労働者と同程度の総収入を得ており、同程度の課税対象であった。これとは対照的に、中欧・東欧の強制労働者は、ドイツ人労働者に支払われた総収入のせいぜい2分の1程度で、社会給付もはるかに少なかった[1]。強制労働や強制収容所の囚人であった強制労働者は、賃金や給付金を受け取ったとしても、ほとんど受け取らなかった[1]。中・東欧の強制労働者(対西欧諸国の強制労働者)の純収入の不足は、強制労働者が国内または海外の家族に送金できた賃金貯蓄によって説明される(表参照)。

ナチスは、ドイツ人と外国人労働者との性的関係の禁止令を出した[16]。 このような関係を防ぐために、ヴォルクストゥム(「人種意識」)を広めるための努力が繰り返し行われた[17]:139。 パンフレットは、例えば、すべてのドイツ人女性に対し、ドイツに連れてこられたすべての外国人労働者との肉体的な接触を避けるよう、彼女たちの血に危険を及ぼすものとして指示した[18]。それに従わない女性は投獄された[17]:212。 労働者との交際でさえも危険視され、1940年から1942年にかけてのパンフレットキャンペーンで標的にされた[17]:211-2。ドイツ国防軍の兵士とSS将校はそのような制限から免除された。第三帝国時代、少なくとも34,140人の東欧女性がワパンカŁapankas(軍による誘拐襲撃)で逮捕され、ドイツ軍の売春宿や収容所の売春宿で「性奴隷」として奉仕させられたと推定されている[19][20]。そこでは西部戦線とは異なりアルコールは禁止され、被害者たちは週に一度性器検査を受けた[21]。 ワルシャワだけでも、1942年9月、軍の警備のもと、このような施設が5つ設置され、それぞれ20以上の部屋があった。西部戦線とは異なりアルコールは禁止され、被害者は週に一度性器検査を受けた[22]。

フランスの造船所

[編集]海軍基地で働くフランス人労働者は、ドイツ海軍に不可欠な労働力を提供し、大西洋の戦いにおいてナチス・ドイツを支えた。1939年まで、ドイツ海軍の計画では、開戦までに資源を増強する時間があると想定していた。フランスが陥落し、ブレスト港、ロリアン港、サン・ナゼール港が使用可能になったとき、これらの修理・整備施設に従事するドイツ人が不足していたため、フランスの労働力に大きく依存することになった。1940年末、ドイツ海軍は大西洋沿岸の基地で働くためにヴィルヘルムスハーフェンから2,700人の熟練労働者を要請したが、これは3,300人しかいなかった。

この同じ要請には、機械やエンジン製造に熟練した870人の人員も含まれていたが、ヴィルヘルムスハーフェンにはこれらの技能を持つ者が725人しかいなかった。この熟練工不足は、フランス海軍造船所の労働者で占められていた。1941年2月、ブレストの海軍造船所には、6,349人のフランス人労働者に対し、470人のドイツ人労働者しかいなかった。1941年4月、フランス人労働者はシャルンホルストの欠陥のある過熱蒸気発生装置を交換し、作業は遅々として進まなかったが、シャルンホルストの艦長の意見では、ドイツの造船所で得られるよりも良い水準であった。1942年10月、ヴァルター・マチアエ海軍大将が委託した、フランス造船所労働者の撤退(ロリアン潜水艦基地での空襲で32名のフランス人死者が出たため、その可能性が考えられた)による潜在的な影響についての評価では、水上艦隊の修理はすべて中止され、Uボートの修理は30%削減されると述べられていた。フランソワ・ダルラン提督は 1940 年9月30日、ドイツからの協力要請を断るのは無駄だと述べた。1942 年9月、占領地域のフランス海軍司令官ジェルマン・ポール・ジャルデル少将は、 「我々は、工廠で働く労働者がドイツではなく工廠で働くことに特別な関心を持ってい る」と述べた。現実的な観点からは、フランスの労働者は雇用を必要としており、ドイツで働くために徴兵される可能性もあった(100万人の労働者がそうであったように[1])。少数の労働者は戦争労働の遂行に反対したが、大多数はドイツ軍によって意欲的で効率的な労働者であると認められた[23]。

Numbers

[編集]1944年の夏の終わりには、ドイツの記録にはドイツ領内の760万人の外国人民間労働者と捕虜が記載されており、そのほとんどは強制連行によって連れてこられたものであった[13]。1944年までに、奴隷労働者はドイツの全労働力の4分の1を占め、ドイツの工場の大部分には捕虜がいた[13][24]。ナチスはまた、イギリスへの侵攻が成功した場合に、「17歳から45歳までの健常な男子人口」をヨーロッパに抑留し、移送する計画も持っていた。

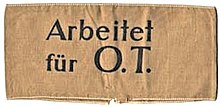

組織トッド

[編集]第二次世界大戦中にドイツと戦争した国またはドイツに占領された国、およびそれらの国の国民による、帝国および帝国の機関に対する第二次世界大戦に起因する請求権(ドイツ占領の費用、占領中に取得した清算勘定上の債権、帝国金融公社に対する請求権を含む)の検討は、賠償問題が最終的に解決されるまで延期されるものとする。

The Organisation Todt was a Nazi era civil and military engineering group in Nazi Germany, eponymously named for its founder Fritz Todt, an engineer and senior Nazi figure. The organization was responsible for a huge range of engineering projects both in pre-World War II Germany, and in all of occupied Europe from France to Russia. Todt became notorious for using forced labour. Most of the so-called "volunteer" Soviet POW workers were assigned to the Organisation Todt.[25] The history of the organization falls into three main phases.[26]

- A pre-war period between 1933 and 1938, during which the predecessor of Organisation Todt, the office of General Inspector of German Roadways (Generalinspektor für das deutsche Straßenwesen), was primarily responsible for the construction of the German Autobahn network. The organisation was able to draw on "conscripted" (i.e. compulsory) labour from within Germany through the Reich Labour Service (Reichsarbeitsdienst, RAD).

- The period from 1938 until 1942 after Operation Barbarossa, when the Organisation Todt proper was founded and utilized on the Eastern front. The huge increase in the demand for labour created by the various military and paramilitary projects was met by a series of expansions of the laws on compulsory service, which ultimately obligated all Germans to arbitrarily determined (i.e. effectively unlimited) compulsory labour for the state: Zwangsarbeit.[27] From 1938–40, over 1.75 million Germans were conscripted into labour service. From 1940–42, Organization Todt began its reliance on Gastarbeitnehmer (guest workers), Militärinternierte (military internees), Zivilarbeiter (civilian workers), Ostarbeiter (Eastern workers) and Hilfswillige ("volunteer") POW workers.

- The period from 1942 until the end of the war, with approximately 1.4 million labourers in the service of the Organisation Todt. Overall, 1% were Germans rejected from military service and 1.5% were concentration camp prisoners; the rest were prisoners of war and compulsory labourers from occupied countries. All were effectively treated as slaves and existed in the complete and arbitrary service of a ruthless totalitarian state. Many did not survive the work or the war.[26]

Extermination through labour

[編集]

Millions of Jews were forced labourers in ghettos, before they were shipped off to extermination camps. The Nazis also operated concentration camps, some of which provided free forced labour for industrial and other jobs while others existed purely for the extermination of their inmates. To mislead the victims, at the entrances to a number of camps the lie "work brings freedom" ("arbeit macht frei") was placed, to encourage the false impression that cooperation would earn release. A notable example of labour-concentration camp is the Mittelbau-Dora labour camp complex that serviced the production of the V-2 rocket. Extermination through labour was a Nazi German World War II principle that regulated the aims and purposes of most of their labour and concentration camps.[28][29] The rule demanded that the inmates of German World War II camps be forced to work for the German war industry with only basic tools and minimal food rations until totally exhausted.[28][30]

Controversy over compensation

[編集]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l John C. Beyer; Stephen A. Schneider. Forced Labour under Third Reich. Nathan Associates Part1 Archived 2015-08-24 at the Wayback Machine. and Part 2 Archived 2017-04-03 at the Wayback Machine.. 引用エラー: 無効な

<ref>タグ; name "BeyerSchneider"が異なる内容で複数回定義されています - ^ Herbert, Ulrich (1997). Hitler's Foreign Workers: Enforced Foreign Labour in Germany Under the Third Reich. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-47000-5

- ^ Czesław Łuczak (1979). Polityka ludnościowa i ekonomiczna hitlerowskich Niemiec w okupowanej Polsce. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Poznańskie. pp. 136. ISBN 832100010X 11 October 2013閲覧. "Also in: http://www.polishresistance-ak.org/30%20Artykul.htm [Eksploatacja ekonomiczna ziem polskich] (Economic exploitation of Poland's territory) by Dr. Andrzej Chmielarz, Polish Resistance in WW2, Eseje-Artykuły."

- ^ Panayi, Panikos (2005). “Exploitation, Criminality, Resistance. The Everyday Life of Foreign Workers and Prisoners of War in the German Town of Osnabrck, 1939-49”. Journal of Contemporary History 40 (3): 483–502. doi:10.1177/0022009405054568. JSTOR 30036339.

- ^ Johannes-Dieter Steinert. Kleine Ostarbeiter: Child Forced Labor in Nazi Germany and German Occupied Eastern Europe.

- ^ “The Holocaust in Belarus”. Facing History and Ourselves. 29 December 2020閲覧。 “The non-Jewish population was subjected to Nazi terror, too. Hundreds of thousands were deported to Germany as slave laborers, thousands of villages and towns were burned or destroyed, and millions were starved to death as the Germans plundered the entire region. Timothy Snyder estimates that “half of the population of Soviet Belarus was either killed or forcibly displaced during World War II: nothing of the kind can be said of any other European country.””

- ^ Diemut Majer (2003). "Non-Germans" Under the Third Reich: The Nazi Judicial and Administrative System in Germany and Occupied Eastern Europe with Special Regard to Occupied Poland, 1939–1945. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-6493-3

- ^ Gellately, Robert (2002). Backing Hitler: Consent And Coercion In Nazi Germany. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 127. ISBN 0192802917

- ^ Marc Buggeln (2014). Slave Labor in Nazi Concentration Camps. OUP Oxford. 335. ISBN 978-0191017643

- ^ Sohn-Rethel, Alfred Economy and Class Structure of German Fascism, CSE Books, 1978 ISBN 0-906336-01-5

- ^ Marek (2005年10月27日). “Final Compensation Pending for Former Nazi Forced Labourers”. Deutsche Welle. 2008年5月20日閲覧。 See also: “Forced Labour at Ford Werke AG during the Second World War”. The Summer of Truth Website. 2007年10月14日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年5月20日閲覧。

- ^ “Comprehensive List Of German Companies That Used Slave Or Forced Labour During World War II Released”. American Jewish Committee (7 December 1999). 2008年4月8日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年5月20日閲覧。 See also: Roger Cohen (February 17, 1999). “German Companies Adopt Fund For Slave Labourers Under Nazis”. The New York Times. 2008年5月20日閲覧。 “German Firms That Used Slave or Forced Labour During the Nazi Era”. American Jewish Committee (January 27, 2000). 2008年7月17日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ulrich Herbert (16 March 1999). “The Army of Millions of the Modern Slave State: Deported, used, forgotten: Who were the forced workers of the Third Reich, and what fate awaited them?”. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. June 4, 2011時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。January 6, 2013閲覧。

- ^ Alexander von Plato; Almut Leh; Christoph Thonfeld (2010). Hitler's Slaves: Life Stories of Forced Labourers in Nazi-Occupied Europe. Berghahn Books. pp. 251–62. ISBN 978-1845459901

- ^ Template:Cite webの呼び出しエラー:引数 title は必須です。Павел Полуян. “{{{title}}}” (ロシア語). 2008年5月20日閲覧。

- ^ “'Sonderbehandlung erfolgt durch Strang'”. ns-archiv.de. Template:Cite webの呼び出しエラー:引数 accessdate は必須です。

- ^ a b c Hertzstein, Robert Edwin (1978). The War That Hitler Won: The Most Infamous Propaganda Campaign in History. ISBN 9780399118456

- ^ Rupp, Leila J.. Mobilizing Women for War. p. 124-5. ISBN 0-691-04649-2. OCLC 3379930

- ^ Nanda Herbermann; Hester Baer; Elizabeth Roberts Baer (2000) (Google Books). The Blessed Abyss. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. pp. 33‑34. ISBN 0-8143-2920-9 January 12, 2011閲覧。

- ^ Lenten, Ronit (2000). Israel and the Daughters of the Shoah: Reoccupying the Territories of Silence. Berghahn Books. pp. 33–34. ISBN 1-57181-775-1.

- ^ Ostrowska, Joanna; Zaremba, Marcin (May 30, 2009). “Do burdelu, marsz!” (ポーランド語). Polityka 22 (2707): p. 70–72. オリジナルの2010年12月5日時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ Ostrowska, Joanna; Zaremba, Marcin (May 30, 2009). “Do burdelu, marsz! [To the brothel, march!]” (ポーランド語). Polityka 22 (2707): pp. 70–72. オリジナルの2010年12月5日時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ Hellwinkel, Lars (2014). Hitler's Gateway to the Atlantic: German Naval Bases in France 1940–1945 (Kindle ed.). Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. p. passim. ISBN 978-1848321991

- ^ Allen, Michael Thad (2002). The Business of Genocide. The University of North Carolina Press. pp. 1. ISBN 9780807826775 See also: Herbert. “Forced Labourers in the "Third Reich"”. International Labour and Working-Class History. 2008年4月15日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年5月20日閲覧。

- ^ Christian Streit: Keine Kameraden: Die Wehrmacht und die Sowjetischen Kriegsgefangenen, 1941–1945, Bonn: Dietz (3. Aufl., 1. Aufl. 1978), ISBN 3-8012-5016-4 – "Between 22 June 1941 and the end of the war, roughly 5.7 million members of the Red Army fell into German hands. In January 1945, 930,000 were still in German camps. A million at most had been released, most of whom were so-called "volunteer" (Hilfswillige) for (often compulsory) auxiliary service in the Wehrmacht. Another 500,000, as estimated by the Army High Command, had either fled or been liberated. The remaining 3,300,000 (57.5 percent of the total) had perished."

- ^ a b HBC (25 September 2009). “Organization Todt”. World War II: German Military Organizations. HBC Historical Clothing. 16 October 2014閲覧。 “Sources: 1. Gruner, Wolf. Jewish Forced Labor Under the Nazis. Economic Needs and Racial Aims, 1938–1944 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006), published in association with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. 2. U.S. War Department, "The Todt Organization and Affiliated Services" Tactical and Technical Trends No. 30 (July 29, 1943).”

- ^ Verordnung zur Sicherstellung des Kräftebedarfs für Aufgaben von besonderer staatspolitischer Bedeutung of October 15, 1938 (Notdienstverordnung), RGBl. 1938 I, Nr. 170, S. 1441–1443; Verordnung zur Sicherstellung des Kräftebedarfs für Aufgaben von besonderer staatspolitischer Bedeutung of February 13, 1939, RGBl. 1939 I, Nr. 25, S. 206f.; Gesetz über Sachleistungen für Reichsaufgaben (Reichsleistungsgesetz) of September 1, 1939, RGBl. 1939 I, Nr. 166, S. 1645–1654. [ RGBl = Reichsgesetzblatt, the official organ for he publication of laws.] For further background, see Die Ausweitung von Dienstpflichten im Nationalsozialismus Archived 2005-11-27 at the Wayback Machine., a working paper of the Forschungsprojekt Gemeinschaften, Humboldt University, Berlin, 1996–1999.

- ^ a b Stanisław Dobosiewicz (1977) (ポーランド語). Mauthausen/Gusen; obóz zagłady (Mauthausen/Gusen; the Camp of Doom). Warsaw: Ministry of National Defense Press. pp. 449. ISBN 83-11-06368-0

- ^ Wolfgang Sofsky (1999). The Order of Terror: The Concentration Camp. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 352. ISBN 0-691-00685-7

- ^ Władysław Gębik (1972) (ポーランド語). Z diabłami na ty (Calling the Devils by their Names). Gdańsk: Wydawnictwo Morskie. pp. 332 See also: Günter Bischof; Anton Pelinka (1996). Austrian Historical Memory and National Identity. Transaction Publishers. pp. 185–190. ISBN 1-56000-902-0 and Cornelia Schmitz-Berning (1998). “Vernichtung durch Arbeit” (ドイツ語). Vokabular des Nationalsozialismus (Vocabulary of the National Socialism). Walter de Gruyter. pp. 634. ISBN 3-11-013379-2

To facilitate the economy after the war, certain categories of the victims of Nazism were excluded from compensation from the German Government; those were the groups with the least amount of political pressure they could have brought to bear, and many forced labourers from the Eastern Europe fall into that category.[1] There has been little initiative on the part of the German government or business to compensate the forced labourers from the war period.[2]

As stated in the London Debt Agreement of 1953:

To this date, there are arguments that such settlement has never been fully carried out and that Germany post-war development has been greatly aided, while the development of victim countries stalled.[2]

A prominent example of a group which received almost no compensation for their time as forced labourer in Nazi Germany are the Polish forced labourers. According to the Potsdam Agreements of 1945, the Poles were to receive reparations not from Germany itself, but from the Soviet Union share of those reparations; due to the Soviet pressure on the Polish communist government, the Poles agreed to a system of repayment that de facto meant that few Polish victims received any sort of adequate compensation (comparable to the victims in Western Europe or Soviet Union itself). Most of the Polish share of reparations was "given" to Poland by Soviet Union under the Comecon framework, which was not only highly inefficient, but benefited Soviet Union much more than Poland. Under further Soviet pressure (related to the London Agreement on German External Debts), in 1953 the People's Republic of Poland renounced its right to further claims of reparations from the successor states of Nazi Germany. Only after the fall of communism in Poland in 1989/1990 did the Polish government try to renegotiate the issue of reparations, but found little support in this from the German side and none from the Soviet (later, Russian) side.[1]

The total number of forced labourers under Nazi rule who were still alive as of August 1999 was 2.3 million.[2] The German Forced Labour Compensation Programme was established in 2000; a forced labour fund paid out more than 4.37 billion euros to close to 1.7 million of then-living victims around the world (one-off payments of between 2,500 and 7,500 euros).[3] Germany Chancellor Angela Merkel stated in 2007 that "Many former forced labourers have finally received the promised humanitarian aid"; she also conceded that before the fund was established nothing had gone directly to the forced labourers.[3] German president Horst Koehler stated

- It was an initiative that was urgently needed along the journey to peace and reconciliation... At least, with these symbolic payments, the suffering of the victims has been publicly acknowledged after decades of being forgotten.[3]

参照

[編集]- Private sector participation in Nazi crimes

- Arbeitseinsatz, (forced labour deployment)

- Totaleinsatz, a colloquial term used for a subset of the Arbeitseinsatz program concerning 400,000 Czechs

- Polnischer Baudienst im Generalgouvernement, (Polish Construction Service in the General Government)

- Deutsche Wirtschaftsbetriebe (DWB), (German Economic Enterprises)

- Fritz Sauckel

- Italian military internees

- Service du travail obligatoire (STO), (Compulsory Work Service in Vichy France)

- Forced labor of Germans after World War II

脚注

[編集]Informational notes

'Citations'Further reading

- Homze, Edward L. Foreign Labor in Nazi Germany (Princeton UP 1967)

- Edward L. Homze (Dec 1980). “Review of Benjamin B. Ferencz, Less Than Slaves: Jewish Forced Labour and the Quest for Compensation”. The American Historical Review 85 (5): 1225. doi:10.2307/1853330. JSTOR 1853330.

- Kogon, Eugen (2006). The Theory and Practice of Hell: The German Concentration Camps and the System Behind Them. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 0-374-52992-2

- Mazower, Mark (2008). “Chapter 10: Workers”. Hitler's Empire: How the Nazis Ruled Europe. Penguin Press. p. 294. ISBN 9780143116103

- Mędykowski, Witold Wojciech (2018). Macht Arbeit Frei?. Academic Studies Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv75d8v5. ISBN 9781618115966. JSTOR j.ctv75d8v5

- Ruhs (29 May 2011). “Foreign Workers in the Second World War. The Ordeal of Slovenians in Germany”. aventinus nova. Template:Cite webの呼び出しエラー:引数 accessdate は必須です。

- Tooze, Adam (2007). The Wages of Destruction. Viking Press. pp. 476–85, 538–49. ISBN 978-0-670-03826-8

外部リンク

[編集]- Compensation for Forced Labour in World War II: The German Compensation Law of 2 August 2000

- German compensation law

- Report on victim compensation, International Organization for Migration

- Forced Labour document from Yad Vashem[要検証]

- "Forced and Slave Labour in Nazi-Dominated Europe, 1933 to 1945", United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Symposium (2002)

- International Red Cross

- Nazi Forced Labour Documentation Centre in Berlin-Schoeneweide

- Forced Labour at Salamander AG

- Claims against Germany

- International Tracing Service – Glossary

[[Category:ナチス・ドイツの戦争犯罪]] [[Category:ナチス・ドイツの経済]] [[Category:未査読の翻訳があるページ]]

- ^ a b Jeanne Dingell. “The Question of the Polish Forced Labourer during and in the Aftermath of World War II: The Example of the Warthegau Forced Labourers”. remember.org. 2008年6月2日閲覧。

- ^ a b c 引用エラー: 無効な

<ref>タグです。「BeyerSchneider」という名前の注釈に対するテキストが指定されていません - ^ a b c Erik Kirschbaum (12 June 2007). “Germany ends war chapter with "slave fund" closure”. Reuters. 2008年7月24日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年7月13日閲覧。