「知能指数」の版間の差分

m →出典 |

m Cewbot: ウィキ文法修正 102: PMID with incorrect syntax |

||

| 310行目: | 310行目: | ||

ヒトの17,000以上の遺伝子のうち、非常に大きな割合が脳の発達と機能に影響を及ぼすと考えられている<ref>{{Cite journal2|last1=Pietropaolo|first1=S.|last2=Crusio|first2=W. E.|year=2010|title=Genes and cognition|journal={{仮リンク|Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science|en|Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science|label=Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science}}|volume=2|issue=3|pages=345–352|doi=10.1002/wcs.135|pmid=26302082|author-link2=Wim Crusio}}</ref>。多くの個別の遺伝子がIQと関連していることが報告されているが、強い効果を示すものはない。DearyとColleagues(2009)は、IQに対する強力な単一遺伝子の効果の発見は複製されていないと報告している{{Sfn|Deary|Johnson|Houlihan|2009}}。成人と子供の通常の知的差異と遺伝子の関連性に関する最近の発見は、どの遺伝子も弱い効果しかないことを示し続けている<ref name="Davies2011">{{Cite journal2|year=2011|title=Genome-wide association studies establish that human intelligence is highly heritable and polygenic|journal=Mol Psychiatry|volume=16|issue=10|pages=996–1005|doi=10.1038/mp.2011.85|pmc=3182557|pmid=21826061|vauthors=Davies G, Tenesa A, Payton A, Yang J, Harris SE, Liewald D, Ke X, Le Hellard S|display-authors=etal}}</ref><ref name="Benyamin2013">{{Cite journal2|year=2013|title=Childhood intelligence is heritable, highly polygenic and associated with FNBP1L|journal=Mol Psychiatry|volume=19|issue=2|pages=253–258|doi=10.1038/mp.2012.184|pmc=3935975|pmid=23358156|display-authors=8|vauthors=Benyamin B, Pourcain B, Davis OS, Davies G, Hansell NK, Brion MJ, Kirkpatrick RM, Cents RA, Franic S, Miller MB, Haworth CM, Meaburn E, Price TS, Evans DM, Timpson N, Kemp J, Ring S, McArdle W, Medland SE, Yang J, Harris SE, Liewald DC, Scheet P, Xiao X, Hudziak JJ, de Geus C, ((Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 2)), Jaddoe VW, Starr JM, Verhulst FC, Pennell C, Tiemeier H, Iacono WG, Palmer LJ, Montgomery GW, Martin NG, Boomsma DI, Posthuma D, McGue M, Wright MJ, Smith GD, Deary IJ, Plomin R, Visscher PM}}</ref>。 |

ヒトの17,000以上の遺伝子のうち、非常に大きな割合が脳の発達と機能に影響を及ぼすと考えられている<ref>{{Cite journal2|last1=Pietropaolo|first1=S.|last2=Crusio|first2=W. E.|year=2010|title=Genes and cognition|journal={{仮リンク|Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science|en|Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science|label=Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science}}|volume=2|issue=3|pages=345–352|doi=10.1002/wcs.135|pmid=26302082|author-link2=Wim Crusio}}</ref>。多くの個別の遺伝子がIQと関連していることが報告されているが、強い効果を示すものはない。DearyとColleagues(2009)は、IQに対する強力な単一遺伝子の効果の発見は複製されていないと報告している{{Sfn|Deary|Johnson|Houlihan|2009}}。成人と子供の通常の知的差異と遺伝子の関連性に関する最近の発見は、どの遺伝子も弱い効果しかないことを示し続けている<ref name="Davies2011">{{Cite journal2|year=2011|title=Genome-wide association studies establish that human intelligence is highly heritable and polygenic|journal=Mol Psychiatry|volume=16|issue=10|pages=996–1005|doi=10.1038/mp.2011.85|pmc=3182557|pmid=21826061|vauthors=Davies G, Tenesa A, Payton A, Yang J, Harris SE, Liewald D, Ke X, Le Hellard S|display-authors=etal}}</ref><ref name="Benyamin2013">{{Cite journal2|year=2013|title=Childhood intelligence is heritable, highly polygenic and associated with FNBP1L|journal=Mol Psychiatry|volume=19|issue=2|pages=253–258|doi=10.1038/mp.2012.184|pmc=3935975|pmid=23358156|display-authors=8|vauthors=Benyamin B, Pourcain B, Davis OS, Davies G, Hansell NK, Brion MJ, Kirkpatrick RM, Cents RA, Franic S, Miller MB, Haworth CM, Meaburn E, Price TS, Evans DM, Timpson N, Kemp J, Ring S, McArdle W, Medland SE, Yang J, Harris SE, Liewald DC, Scheet P, Xiao X, Hudziak JJ, de Geus C, ((Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 2)), Jaddoe VW, Starr JM, Verhulst FC, Pennell C, Tiemeier H, Iacono WG, Palmer LJ, Montgomery GW, Martin NG, Boomsma DI, Posthuma D, McGue M, Wright MJ, Smith GD, Deary IJ, Plomin R, Visscher PM}}</ref>。 |

||

2017年に約78,000人の被験者を対象に行われた[[メタアナリシス]]では、知能に関連する52の遺伝子が特定された<ref>Sniekers S, Stringer S, Watanabe K, Jansen PR, Coleman JRI, Krapohl E, Taskesen E, Hammerschlag AR, Okbay A, Zabaneh D, Amin N, Breen G, Cesarini D, Chabris CF, Iacono WG, Ikram MA, Johannesson M, Koellinger P, Lee JJ, Magnusson PKE, McGue M, Miller MB, Ollier WER, Payton A, Pendleton N, Plomin R, Rietveld CA, Tiemeier H, van Duijn CM, Posthuma D. Genome-wide association meta-analysis of 78,308 individuals identifies new loci and genes influencing human intelligence. Nat Genet. 2017 Jul;49(7):1107-1112. doi: 10.1038/ng.3869. Epub 2017 May 22. Erratum in: Nat Genet. 2017 Sep 27;49(10 ):1558. PMID |

2017年に約78,000人の被験者を対象に行われた[[メタアナリシス]]では、知能に関連する52の遺伝子が特定された<ref>Sniekers S, Stringer S, Watanabe K, Jansen PR, Coleman JRI, Krapohl E, Taskesen E, Hammerschlag AR, Okbay A, Zabaneh D, Amin N, Breen G, Cesarini D, Chabris CF, Iacono WG, Ikram MA, Johannesson M, Koellinger P, Lee JJ, Magnusson PKE, McGue M, Miller MB, Ollier WER, Payton A, Pendleton N, Plomin R, Rietveld CA, Tiemeier H, van Duijn CM, Posthuma D. Genome-wide association meta-analysis of 78,308 individuals identifies new loci and genes influencing human intelligence. Nat Genet. 2017 Jul;49(7):1107-1112. doi: 10.1038/ng.3869. Epub 2017 May 22. Erratum in: Nat Genet. 2017 Sep 27;49(10 ):1558. PMID 28530673; PMCID: PMC5665562.</ref>。{{仮リンク|FNBP1L|en|FNBP1L|label=FNBP1L}}は、成人と子供の両方の知能に最も関連のある単一の遺伝子であると報告されている<ref>Benyamin B, Pourcain B, Davis OS, Davies G, Hansell NK, Brion MJ, Kirkpatrick RM, Cents RA, Franić S, Miller MB, Haworth CM, Meaburn E, Price TS, Evans DM, Timpson N, Kemp J, Ring S, McArdle W, Medland SE, Yang J, Harris SE, Liewald DC, Scheet P, Xiao X, Hudziak JJ, de Geus EJ; Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 2 (WTCCC2); Jaddoe VW, Starr JM, Verhulst FC, Pennell C, Tiemeier H, Iacono WG, Palmer LJ, Montgomery GW, Martin NG, Boomsma DI, Posthuma D, McGue M, Wright MJ, Davey Smith G, Deary IJ, Plomin R, Visscher PM. Childhood intelligence is heritable, highly polygenic and associated with FNBP1L. Mol Psychiatry. 2014 Feb;19(2):253-8. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.184. Epub 2013 Jan 29. PMID 23358156; PMCID: PMC3935975.</ref>。 |

||

=== 遺伝子-環境相互作用 === |

=== 遺伝子-環境相互作用 === |

||

2024年4月11日 (木) 01:33時点における版

| 知能指数 | |

|---|---|

| 医学的診断 | |

![[picture of an example IQ test item]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ec/Raven_Matrix.svg/290px-Raven_Matrix.svg.png) レーヴン漸進的マトリックスによる試験 | |

| ICD-10-PCS | Z01.8 |

| ICD-9-CM | 94.01 |

| 心理学 |

|---|

| 基礎心理学 |

| 応用心理学 |

| 一覧 |

|

|

知能指数(ちのうしすう、英: Intelligence Quotient)(IQ)は、標準化検査または知性を評価するために設計された下位検査から得られる合計得点のことである[1]。略語「IQ」は、心理学者のウィリアム・スターンが1912年の著書で提唱したヴロツワフ大学における知能検査の採点方法を指す「Intelligenzquotient」というドイツ語の用語に由来する[2]。

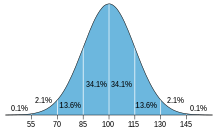

歴史的に、IQは知能検査を実施して得られた人の精神年齢得点を、年と月で表されたその人の暦年齢で割って得られた得点であった。そして得られた分数(商)に100を掛けてIQ得点とした[3]。現代のIQ検査では、素点が平均100、標準偏差15の正規分布に変換される[4]。その結果、約3分の2の人口がIQ85からIQ115の間に分布し、130以上と70未満がそれぞれ約2%となる[5][6]。

知能検査の得点は知能の推定値である。距離や質量などとは異なり、「知能」の概念が抽象的であるため、知能の具体的な尺度を得ることはできない[7]。IQの得点は、栄養[8][9][10]、親の社会経済状況[11][12]、罹病率と死亡率[13][14]、親の社会的地位[15]、周産期の環境[16]などの要因と関連があることが示されている。IQの遺伝率は約1世紀にわたって研究されてきたが、遺伝率の推定値の重要性[17][18]と遺伝のメカニズム[19]については依然として議論がある。

IQの得点は、教育的配置、知的障害の評価、求職者の評価に使用される。研究の文脈では、仕事の業績[20]や収入[21]の予測因子として研究されてきた。また、集団における心理測定学的知能の分布や、それと他の変数との相関を研究するためにも使用される。多くの集団におけるIQ検査の素点は、20世紀初頭以降、10年で3ポイントに相当する平均速度で上昇しており、この現象はフリン効果と呼ばれる。下位検査の得点の増加パターンの違いを調べることで、人間の知能に関する現在の研究に情報を提供することもできる。

歴史

IQ検査の前兆

歴史的に、IQ検査が考案される以前から、日常生活における行動を観察することで、人々を知性のカテゴリーに分類しようとする試みがあった[22][23]。検査室外での行動観察による知能分類と、IQ検査による分類は、いずれも特定のケースで使用される「知能」の定義と、分類手順の信頼性および推定誤差に依存する。

イギリスの統計学者フランシス・ゴルトン(1822–1911)は、人の知能を評価するための標準化された検査を作成する最初の試みを行った。心理測定法と統計的手法の人間の多様性研究への応用、および人間の特性の遺伝研究のパイオニアであり、知能は主に遺伝の産物であると信じていた(遺伝子を意味していたわけではないが、粒子的遺伝のいくつかのメンデル以前の理論を展開した)[24][25][26]。彼は、知能と反射、筋力、頭部のサイズなどの他の観察可能な特性との間に相関関係が存在するはずだと仮説を立てた[27]。1882年に世界初の知能検査センターを設立し、1883年に「人間の能力とその発達に関する調査」を発表して、自身の理論を提示した。様々な身体的変数についてデータを収集した後、そのような相関関係を示すことができず、最終的にこの研究を断念した[28][29]。

フランスの心理学者アルフレッド・ビネーは、ヴィクトール・アンリとテオドール・シモンとともに、1905年にビネー・シモン尺度を発表し、言語能力に焦点を当てたことでより成功を収めた。これは学童の「精神遅滞」を特定することを目的としていた[30]が、これらの子供たちが「病気」(「遅れている」のではない)であり、したがって学校から取り除かれて施設でケアを受けるべきだという精神科医の主張とは特に対照的であった[31]。ビネー・シモン尺度の得点は、子供の精神年齢を明らかにするものであった。例えば、6歳児が通常6歳児に合格するすべての課題に合格したが、それ以上のものには合格しなかった場合、その子供の精神年齢は暦年齢と一致し、6.0となる(Fancher, 1985)。ビネーは知能が多面的なものであると考えていたが、実用的な判断の支配下にあると考えていた。

ビネーの見解では、この尺度には限界があり、知能の驚くべき多様性とそれに続く量的ではなく質的な尺度を用いて研究する必要性を強調した(White, 2000)。アメリカの心理学者ヘンリー・H・ゴダードが1910年にその翻訳を発表した。スタンフォード大学のアメリカの心理学者ルイス・ターマンがビネー・シモン尺度を改訂し、その結果スタンフォード・ビネー式知能検査(1916)が生まれた。これは数十年にわたってアメリカで最も人気のある検査となった[30][32][33][34]。

一般因子(g)

多種多様なIQ検査には、非常に幅広い項目内容が含まれている。視覚的な検査項目もあれば、言語的な検査項目も多い。検査項目は、抽象的推論問題を基にしたものから、算数、語彙、一般知識に特化したものまで様々である。

イギリスの心理学者チャールズ・スピアマンは、1904年に検査間の相関の最初の正式な因子分析を行った。彼は、一見無関係に見える学校の教科における子供たちの成績が正の相関を示すことを観察し、これらの相関は、あらゆる種類の精神検査の成績に影響を与える基礎的な一般的精神能力の影響を反映していると推論した。彼は、すべての精神的能力は、単一の一般的能力因子と多数の狭い課題特異的能力因子の観点から概念化できると示唆した。スピアマンはこれを「一般因子」の意味でgと名付け、特定の課題に対する特定の因子または能力をsと名付けた[35]。IQ検査を構成する検査項目の集合体において、gを最もよく測定する得点は、すべての項目得点と最も高い相関を示す合成得点である。典型的には、IQ検査バッテリーの「g負荷」合成得点は、検査項目の内容全体にわたる抽象的推論における共通の強みを含んでいるように見える[要出典]。

第一次世界大戦におけるアメリカ軍の選抜

第一次世界大戦中、陸軍は新兵を評価し、適切な任務に割り当てる方法を必要としていた。これにより、ロバート・ヤーキーズがいくつかの精神検査を開発することになったが、彼はターマンやゴダードを含むアメリカ心理測定学の主要な遺伝学者と協力してこの検査を作成した[36]。この検査はアメリカで論争を引き起こし、多くの公の議論を巻き起こした。英語を話せない人や詐病が疑われる人のために、非言語的または「パフォーマンス」検査が開発された[30]。ビネー・シモン検査のゴダードによる翻訳に基づいて、この検査は将校訓練のための人員選抜に影響を与えた。

...これらの検査は、特に将校訓練のための人員選抜において大きな影響力を持っていた。戦争開始時、陸軍と国家警備隊は9,000人の将校を抱えていた。終戦時には20万人の将校が存在し、そのうちの3分の2はこの検査が適用された訓練キャンプでキャリアをスタートさせていた。一部のキャンプでは、Cより低い得点の者は将校訓練の対象とならなかった。[36]

合計175万人の男性が検査を受け、これらの結果は大量生産された最初の知能検査となったが、キャンプごとの検査実施の高い変動性や、知能ではなくアメリカ文化への精通度を試す質問があったことなどから、疑わしく使用不可能なものと考えられた[36]。戦後、陸軍の心理学者によって宣伝された肯定的な広報は、心理学を尊重される分野にするのに役立った[37]。その後、アメリカでは心理学の仕事と資金が増加した[38]。集団知能検査が開発され、学校や産業界で広く使用されるようになった[39]。

これらの検査の結果は、当時の人種差別と国家主義を再確認するものであり、いくつかの議論の余地のある仮定に基づいていたため、論争の的となり、疑わしいものとされている。その仮定とは、知能は遺伝的で生得的であり、単一の数値に帰することができること、検査は体系的に実施されたこと、検査問題は実際に環境要因を包含するのではなく、生得的な知能を検査していたということである[36]。また、この検査により、移民の増加という文脈において排外主義的な物語が強化され、1924年移民制限法の成立に影響を与えた可能性がある[36]。

L.L.サーストンは、言語理解、語流暢性、数的能力、空間視覚化、連想記憶、知覚速度、推論、帰納の7つの無関係な因子を含む知能モデルを主張した。広く使用されてはいないが、サーストンのモデルは後の理論に影響を与えた[30]。

デイヴィッド・ウェクスラーは1939年に自身の検査の初版を作成した。徐々に人気が高まり、1960年代にスタンフォード・ビネー式を追い抜いた。IQ検査に共通することだが、新しい研究を取り入れるために何度か改訂されている。一つの説明は、心理学者と教育者がビネーの単一の得点よりも多くの情報を求めていたということである。ウェクスラーの10以上の下位検査がこれを提供した。もう一つの説明は、スタンフォード・ビネー検査が主に言語能力を反映していたのに対し、ウェクスラー検査は非言語能力も反映していたということである。スタンフォード・ビネー検査も何度か改訂され、現在ではウェクスラー検査といくつかの点で類似しているが、ウェクスラー検査はアメリカで最も人気のある検査であり続けている[30]。

IQ検査とアメリカにおける優生学運動

優生学は、劣っていると判断された人々や集団を排除し、優れていると判断された人々を促進することで、人類の遺伝的な質を向上させることを目的とした一連の信念と実践である[40][41][42]。優生学は19世紀後半からアメリカ合衆国が第二次世界大戦に参戦するまでの革新主義時代に、アメリカの歴史と文化において重要な役割を果たした[43][44]。

アメリカの優生学運動は、イギリスの科学者サー・フランシス・ゴルトンの生物学的決定論の考えに根ざしていた。1883年、ゴルトンは初めて優生学という言葉を使って、人間の遺伝子の生物学的改良と「よく生まれた」という概念を表した[45][46]。彼は、人の能力の差は主に遺伝によって獲得されるものであり、優生学は人為選択によって実施することで人類の全体的な質を向上させ、人間が自らの進化を導くことができると信じていた[47]。

ヘンリー・H・ゴダードは優生学者だった。1908年、彼は自身のバージョンである『The Binet and Simon Test of Intellectual Capacity』を発表し、この検査を親切に宣伝した。彼はすぐにこの尺度の使用を公立学校(1913年)、移民(エリス島、1914年)、法廷(1914年)に拡大した[48]。

ゴルトンが肯定的な特性のための選択的育種によって優生学を促進したのとは異なり、ゴダードはアメリカの優生学運動と歩調を合わせ、「望ましくない」特性を排除することを目指した[49]。ゴダードは検査で良い成績を収めなかった人々を指す言葉として「低能」という用語を使用した。彼は、「低能」は遺伝によって引き起こされると主張し、したがって低能な人々は施設での隔離または不妊手術によって出産を防ぐべきだと論じた[48]。当初、不妊手術の対象は障害者だったが、後に貧困層にも拡大された。ゴダードの知能検査は、強制不妊手術の法律を推進するために優生学者に支持された。各州は異なるペースで不妊手術法を採択した。1927年のバック対ベル事件で最高裁がその合憲性を支持したこれらの法律により、アメリカでは6万人以上が不妊手術を受けることを余儀なくされた[50]。

カリフォルニア州の不妊手術プログラムは非常に効果的だったため、ナチスは「不適格者」の出生を防ぐ方法についてアドバイスを求めて政府に相談した[51]。アメリカの優生学運動はナチスドイツの恐怖を受けて1940年代に勢いを失ったが、優生学の提唱者たち(ナチスの遺伝学者オトマー・フォン・フェルシュアーを含む)はアメリカでの活動とアイデアの促進を続けた[51]。その後の数十年間、優生学の原則の一部は選択的生殖の自主的な手段として復活し、「新優生学」と呼ぶ人もいる[52]。IQ(およびその代理)と遺伝子を検査し相関付けることが可能になるにつれ[53]、倫理学者と胚の遺伝子検査企業は、この技術を倫理的に展開する方法を理解しようとしている[54]。

キャッテル-ホーン-キャロル理論

レイモンド・キャッテル(1941)は、スピアマンの一般知能の概念を改訂する中で、2種類の認知能力を提唱した。流動性知能(Gf)は、推論を用いて新しい問題を解決する能力と仮定され、結晶性知能(Gc)は、教育と経験に大きく依存する知識ベースの能力と仮定された。さらに、流動性知能は加齢とともに低下すると仮定されたのに対し、結晶性知能は加齢の影響に対して概ね耐性があると考えられた。この理論はほとんど忘れ去られていたが、彼の弟子のジョン・L・ホーン(1966)によって復活した。ホーンは後にGfとGcは他のいくつかの因子の中の2つに過ぎないと主張し、最終的に9または10の広範な能力を特定した。この理論はGf-Gc理論と呼ばれ続けた[30]。

ジョン・B・キャロル(1993)は、以前のデータを包括的に再分析した後、3つのレベルを持つ階層モデルである三層理論を提唱した。最下層は、高度に専門化された狭い能力(例えば、帰納、つづり能力)で構成される。第2層は、広範な能力で構成される。キャロルは8つの第2層の能力を特定した。キャロルは、最上層である第3層の表現として、スピアマンの一般知能の概念を概ね受け入れた[55][56]。

1999年、キャッテルとホーンのGf-Gc理論とキャロルの三層理論が融合され、キャッテル-ホーン-キャロル理論(CHC理論)が生まれた。この理論では、gが階層の最上位にあり、その下に10の広範な能力があり、第3層にはさらに70の狭い能力に細分化されている。CHC理論は、現在の多くの広範なIQ検査に大きな影響を与えている[30]。

現代の検査は、必ずしもこれらの広範な能力のすべてを測定するわけではない。例えば、量的知識や読み書き能力は、学業成績の尺度であってIQではないと見なされる場合がある[30]。意思決定速度は、特殊な機器がないと測定が難しいかもしれない。gは以前、人気のあるウェクスラーIQ検査の初期のバージョンにおける非言語または動作性下位検査と言語性下位検査に対応すると考えられていたGfとGcにのみ細分化されることが多かった。より最近の研究では、状況はより複雑であることが示されている[30]。現代の包括的なIQ検査では、単一のIQスコアを報告するだけでは済まされない。全体的なスコアは出すものの、これらのより限定的な能力の多くについてもスコアを出し、個人の特定の長所と短所を明らかにするようになった[30]。

その他の理論

レフ・ヴィゴツキー(1896-1934)は、生涯の最後の2年間に著した論文の中で、子供の発達の最近接領域を検査することを目的とした標準的IQ検査の代替案を提唱した[57][58]。ヴィゴツキーによれば、子供がある程度の指導の下で解決可能な問題の複雑さと難易度の最高レベルは、その子供の潜在的発達のレベルを示すという。この潜在的レベルと、支援なしで達成できる下位レベルとの差が、子供の発達の最近接領域を示す[59]。ヴィゴツキーによれば、実際の発達レベルと発達の最近接領域という2つの指標を組み合わせることで、実際の発達レベルだけを評価するよりもはるかに有益な心理発達の指標が得られるという[60][61]。彼の発達の最近接領域に関するアイデアは、後に多くの心理学的・教育学的理論と実践の中で、特に動的評価の旗印の下で発展させられた。動的評価は、発達の可能性を測定しようとするものである[62][63][64](例えば、ルーベン・フォイヤーシュタインとその仲間の研究では、標準的なIQ検査を批判している。それは、知能や認知機能の特性が「固定的で不変」であるという仮定や受け入れに基づいているというのである)。動的評価は、アン・ブラウンやジョン・D・ブランスフォードの研究、ハワード・ガードナーやロバート・スターンバーグによる多重知能理論の中でさらに洗練されている[65][66]。

ジョイ・ギルフォードの知性の構造(1967)の知能モデルは、3つの次元を用いており、これらを組み合わせると合計120種類の知能が得られた。それは1970年代から1980年代初頭にかけて人気があったが、実際上の問題と理論的批判の両方から人気が薄れた[30]。

アレクサンドル・ルリヤの神経心理学的プロセスに関する初期の研究は、PASS理論(1997)につながった。この理論は、1つの一般的因子だけを見ることは、学習障害、注意障害、知的障害、およびそのような障害に対する介入に取り組む研究者や臨床医にとって不十分であると主張した。PASSモデルは、4種類のプロセス(計画プロセス、注意/覚醒プロセス、同時処理、継次処理)をカバーしている。計画プロセスには、意思決定、問題解決、活動の実行が含まれ、目標設定と自己監視が必要となる。

注意/覚醒プロセスには、特定の刺激に選択的に注意を向け、気が散るものを無視し、警戒心を維持することが含まれる。同時処理には、刺激を集団に統合することが含まれ、関係性の観察が必要となる。継次処理には、刺激を連続した順序に統合することが含まれる。計画と注意/覚醒の構成要素は前頭葉に位置する構造から生じ、同時処理と継次処理は大脳皮質の後部に位置する構造から生じる[67][68][69]。この理論は最近のいくつかのIQ検査に影響を与えており、上述のキャッテル-ホーン-キャロル理論を補完するものと見なされている[30]。

現在の検査

英語圏では、個別に実施されるさまざまなIQ検査が使用されている[70][71][72]。最も一般的に使用されている個別IQ検査シリーズは、成人用のウェクスラー成人知能検査(WAIS)と、学齢期の被検者用のウェクスラー式児童用知能検査(WISC)である。その他の一般的な個別IQ検査(標準得点を「IQ」得点とラベル付けしていないものもある)には、スタンフォード・ビネー式知能検査の現行版、ウッドコック・ジョンソン認知能力検査、カウフマンアセスメントバッテリー子供版、認知評価システム、差異的能力尺度などがある。

他にも様々なIQ検査があり、以下のようなものがある。

- レーヴン漸進的マトリックス

- キャッテル文化フェアIII

- レイノルズ知的能力評価尺度

- サーストンの基本知的能力検査[73][74]

- カウフマン簡易知能検査[75]

- 多次元適性バッテリーII

- ダス-ナグリエリ認知評価システム

- ナグリエリ非言語性能力検査

- 広域知能検査

IQスケールは順序尺度である[76][77][78][79][80]。規準化標本の素点は、通常、平均100、標準偏差15の正規分布に(順位)変換される[4]。標準偏差が15ポイントで、2SDが30ポイントというように、精神能力がIQと線形の関係にあることを意味するわけではなく、IQ50はIQ100の半分の認知能力を意味するわけではない。特に、IQポイントはパーセンテージポイントではない。

信頼性と妥当性

| 生徒 | KABC-II | WISC-III | WJ-III |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 90 | 95 | 111 |

| B | 125 | 110 | 105 |

| C | 100 | 93 | 101 |

| D | 116 | 127 | 118 |

| E | 93 | 105 | 93 |

| F | 106 | 105 | 105 |

| G | 95 | 100 | 90 |

| H | 112 | 113 | 103 |

| I | 104 | 96 | 97 |

| J | 101 | 99 | 86 |

| K | 81 | 78 | 75 |

| L | 116 | 124 | 102 |

信頼性

心理測定の専門家は一般に、IQ検査は統計的信頼性が高いと見なしている[15][83]。信頼性とは、検査の測定一貫性を表す[84]。信頼性の高い検査では、繰り返し実施しても同様のスコアが得られる[84]。全体として、IQ検査は高い信頼性を示すが、同じ検査を異なる機会に受けた場合、検査を受ける人によってスコアが異なることがあり、同じ年齢で異なるIQ検査を受けた場合もスコアが異なることがある。他のすべての統計量と同様に、IQの特定の推定値には、その推定値の不確実性を測定する関連する標準誤差がある。現代の検査では、信頼区間は約10ポイント、報告された測定の標準誤差は約3ポイントまで低くなる可能性がある[85]。報告された標準誤差は、すべての誤差の原因を説明していないため、過小評価されている可能性がある[86]。

低い動機付けや高い不安などの外的影響により、その人のIQ検査スコアが一時的に低下することがある[84]。非常に低いスコアの個人の場合、95%信頼区間が40ポイント以上になる可能性があり、知的障害の診断の正確性を複雑にする可能性がある[87]。同様に、高いIQスコアも母集団の中央値に近いスコアよりも信頼性がかなり低い[88]。160をはるかに超えるIQスコアの報告は疑わしいと考えられている[89]。

知能の尺度としての妥当性

信頼性と妥当性は非常に異なる概念である。信頼性が再現性を反映しているのに対し、妥当性は検査がその目的とする測定を行っているかどうかを指す[84]。IQ検査は一般に知能のいくつかの形態を測定すると考えられているが、例えば創造性や社会的知性を含む人間の知性のより広い定義の正確な尺度としては不十分かもしれない。このため、心理学者のウェイン・ワイテンは、IQ検査の構成概念妥当性は慎重に限定されるべきであり、誇張されるべきではないと主張する[84]。ワイテンによれば、「IQ検査は学業で良い成績を収めるのに必要な知能の種類の妥当な尺度である。しかし、もっと広い意味で知能を評価することが目的なら、IQ検査の妥当性は疑問である」[84]。

一部の科学者は、知能の尺度としてのIQの価値そのものに異議を唱えている。人間を測りあやまったもの(1981年、1996年拡大版)の中で、進化生物学者のスティーヴン・ジェイ・グールドは、IQ検査を現在では否定されている頭蓋計測学による知能決定の慣行と比較し、両者とも物象化の誤謬、すなわち「抽象的な概念を実体に変換する傾向」に基づいていると論じた[90]。グールドの主張は多くの議論を巻き起こした[91][92]。この本は、Discover Magazineの「史上最高の科学書25冊」の1冊に挙げられている[93]。

同様の観点から、キース・スタノビッチのような批評家は、IQ検査のスコアがある種の達成を予測する能力を否定するのではなく、IQ検査のスコアだけに基づいて知能の概念を構築すると、精神能力の他の重要な側面が無視されると主張する[15][94]。人間の認知能力の主要な尺度としてのIQのもう1人の重要な批評家であるロバート・スターンバーグは、知能の概念をgの尺度に還元しても、人間社会で成功を生み出すさまざまなスキルと知識のタイプを十分に説明できないと主張した[95]。

これらの異議にもかかわらず、臨床心理士は一般にIQ検査スコアを多くの臨床目的のために十分な統計的妥当性を持つと見なしている[30][96]。

検査バイアスまたは項目機能差

項目機能差(DIF)は、測定バイアスと呼ばれることもあり、同じ潜在能力を持つ異なる集団(例えば、性別、人種、障害)の参加者が、同じIQ検査の特定の質問に異なる回答をする現象のことである[97]。DIF分析は、他の類似の質問に対する参加者の潜在能力を測定するとともに、検査における特定の項目を測定する。類似したタイプの質問の中で、ある特定の質問に対して一貫して異なる集団の反応が見られる場合、DIFの影響を示している可能性がある。両方の集団が同じ質問に異なる回答をする等しく妥当な機会がある場合は、項目機能差とはみなされない。このようなバイアスは、集団の特性とは独立した文化、教育レベル、その他の要因によって生じる可能性がある。DIFは、同じ基礎となる潜在能力レベルの異なる集団の受験者が、特定の回答を与える可能性が異なる場合にのみ考慮される[98]。このような質問は通常、両方の集団に対して検査を等しく公平にするために削除される。DIFを分析するための一般的な手法は、項目応答理論(IRT)に基づく方法、マンテル・ヘンゼル法、ロジスティック回帰である[98]。

ある2005年の研究では、「予測における差別的妥当性から、WAIS-R検査にはメキシコ系アメリカ人学生の認知能力の尺度としてのWAIS-Rの妥当性を低下させる文化的影響が含まれている可能性がある」ことが示唆されており[99]、白人学生のサンプルと比較して正の相関が弱いことが示された。その他の最近の研究では、南アフリカでIQ検査を使用する際の文化的公平性が疑問視されている[100][101]。スタンフォード・ビネーなどの標準的な知能検査は、自閉症の子供には不適切であることが多い。発達スキルや適応スキルの尺度を使用する代替案は、自閉症の子供の知能の比較的貧弱な尺度であり、自閉症の子供の大多数が低知能であるという誤った主張につながった可能性がある[102]。

フリン効果

20世紀初頭以来、世界のほとんどの地域でIQ検査の素点は上昇している[103][104][105]。新しいバージョンのIQ検査が規準化されると、標準的な採点は、母集団の中央値のパフォーマンスがIQ100のスコアになるように設定される。素点のパフォーマンスが上昇するという現象は、受検者が一定の標準的な採点規則でスコア付けされる場合、IQ検査のスコアは10年あたり平均約3IQポイントの割合で上昇していることを意味する。この現象は、心理学者に注目させるのに最も貢献した著者であるジェームズ・R・フリンにちなんで、ベル・カーブの中でフリン効果と名付けられた[106][107]。

研究者たちは、フリン効果があらゆる種類のIQ検査項目のパフォーマンスに等しく強く現れるのかどうか、いくつかの先進国ではこの効果が終わってしまったのかどうか、この効果に社会的下位集団差があるのかどうか、そしてこの効果の考えられる原因は何なのかという問題を探求してきた[108]。N・J・マッキントッシュによる2011年の教科書『IQとヒューマンインテリジェンス』では、フリン効果はIQが低下するという懸念を払拭したと指摘している。また、それがIQスコア以上の知能の真の増加を表しているのかどうかも問うている[109]。ハーバード大学心理学教授のダニエル・シャクターを筆頭著者とする2011年の心理学教科書では、人間の生得的知能は下がっている可能性があるが、後天的知能は上がっていると指摘している[110]。

研究によると、フリン効果は20世紀後半以降、一部の西洋諸国で鈍化したり、逆転したりしていることが示唆されている。この現象は負のフリン効果と呼ばれている[111]。ノルウェーの徴兵適性検査の記録を調べた研究では、1975年以降に生まれた世代のIQスコアは低下しており、当初の上昇傾向とその後の低下傾向の両方の根本的な原因は、遺伝的というよりも環境的なものであることが示唆された[111]。

年齢

IQは、子供の頃はある程度変化する可能性がある[112]。ある縦断研究では、17歳と18歳の時の検査の平均IQスコアは、5歳、6歳、7歳の時の検査の平均スコアとr = 0.86の相関があり、11歳、12歳、13歳の時の検査の平均スコアとはr = 0.96の相関があった[15]。何十年もの間、実務家のハンドブックやIQ検査の教科書には、成人期の始まり以降、年齢とともにIQが低下することが報告されてきた。しかし、後の研究者たちは、この現象はフリン効果と関連しており、真の加齢効果というよりも部分的にはコーホート効果であると指摘した。最初のウェクスラー式知能検査の標準化が成人の異なる年齢集団のIQの差に注目して以来、IQと加齢に関するさまざまな研究が行われてきた。現在のコンセンサスは、流動性知能は一般に成人初期以降は年齢とともに低下するが、結晶性知能は維持されるというものである。正確なデータを得るには、コーホート効果(被験者の生年)と練習効果(被験者が同じ形式のIQ検査を複数回受ける)の両方を制御する必要がある。ライフスタイルの介入によって高齢まで流動性知能を維持できるかどうかは不明である[113]。

流動性知能または結晶性知能のピークがどの年齢なのかは、まだはっきりとはわかっていない。横断的研究では、特に流動性知能は比較的若い年齢(多くの場合、成人初期)でピークに達することが多いが、縦断的データでは、知能は中年期またはそれ以降まで安定していることが多い。その後、知能はゆっくりと低下するようである[114]。

1948年にアメリカのホンジックが行った研究では、222人の被験者を対象に6歳時と18歳時のIQを比較した(文献によっては、1歳時と18歳時となっている)が、50以上変化した例は0.5%で、30以上変化した例は9%であった。しかしながら、20以上変化した例は35%で、10以上変化した例は85%であり、ある程度は変動するものだということができる。また、狩野広之による1960年の研究では、小学校1年から中学校3年までの児童生徒を対象としてIQの変化を調べたが、「小学校1年生時点のIQはそれ以降大きく変わるケースが多い」ということと、「小学校3年生以上では、IQの変化はかなり少なくなってくる」ということが分かった[115]。2014年にScienceで発表されたスコットランドの千数百人を対象にした追跡調査では、11歳の時に高IQだと、高齢になってからも高IQだと言うことがわかった[116]。知能に影響すると言われていたワインや食生活の差、ダイエット、運動といったものは、子供時代の知能で補正するとその影響が消えてしまうこともわかった[116]。

また、知能研究においてはヘッドスタートを始めとする教育プログラムの効果が参加している間は効果があるものの、参加しなくなると意外に早く薄れていくことはよく知られている[117]。

測定尺度・回数によるIQの違い

同一人物を複数種類の知能検査で測定すれば、違う数値が出ることはありうる。例えば、WISC-III開発時に田中ビネー[118]とWISC-IIIを38人(やや少人数)に対して実施したところ、WISC-IIIの平均FIQが100.1であるのに対し、田中ビネーの平均IQは111.7であった。WISC-Rと田中ビネーの比較でも同じ様な結果は出ており、一般的に「田中ビネーの結果はWISCの結果より10ほど高いと考えた方が良い」と言われている。なおK-ABCとの比較、ITPAとの比較も、どちらも28人を対象として実施されたが、この2つについては大きな乖離はなかった[119]。

なお、田中ビネーV開発時にもWISC-IIIとの比較は行われており、平均5歳11ヶ月の97人に対して実施された結果、田中ビネーVの平均IQ129.9、平均DIQ111.7に対し、WISC-IIIの平均FIQは115.6であった。DIQ基準でいえば拮抗あるいは田中ビネーVがやや低めといえるが、IQ基準では14程度田中ビネーVが高い[120]。

ただし、後述の通りIQは検査の開発時期によって変化するため、これらの得点の相違は、検査の性質の差によるものか、検査の開発時期が異なることによる差か、確かなことは言えない。

同一シリーズの知能検査でも版が違う物で測定すれば、違う数値が出ることはありうる。例えば、WISC-III(WISCの第3版)開発時にWISC-R(WISCの第2版)と比較したところ、WISC-Rの平均FIQは108.9であるのに対し、WISC-IIIの平均FIQは103.3であった(日本版相関係数0.84)。なおフリンの研究によれば、全く同じ知能検査を使用して比較しても、IQは10年で3ポイント程度上昇していく傾向である。この傾向は、レーヴンのマトリシスのような文化的な影響度を最小限にした典型的な非言語性テストでも、いっそう著しく見られるのであり、その原因は不明である。田中ビネー第4版と第5版の間の比較調査は今のところ見当たらないため、こちらは改訂により高く出やすくなったのか低く出やすくなったのかは不明である[119]。

同一人物を同じ知能検査で複数回測定すれば、2回目以降は数値が高くなりがちである。例えば、WISC-IIIを同一対象に14–180日(平均76日)の間隔を置いて再検査したところ、一回目の平均FIQは101.1であるのに対し、2回目の平均FIQは109.4だった。なおVIQは上昇幅が少なかった[119]。

IQ以外の表示法

IQは知能の代表的な表示法であるが、IQ以外にもいくつかの表示法が使われている。

知能偏差値

知能の偏差値を「知能偏差値 (Intelligence Standard Score, ISS)」という。これは、知能を偏差値の形で表示したものであり、50を中心として上に行くほど知能が高いことをあらわしている。特徴としては、母集団の結果にばらつきが多い年齢層とばらつきが少ない年齢層の両方で、正確な表示ができることなどがあげられる。また、標準学力検査の結果も学力偏差値で表示される場合が多いため、IQと学力は比較しにくいが、知能偏差値と学力は比較しやすいという特徴もある。また、DIQはもともと偏差値・標準偏差の考え方を利用した表示法なので、知能偏差値はDIQと簡単に換算できる。伝統的に集団式検査に多い表示法である。

これは偏差知能指数 (DIQ) とは異なる。DIQは中心値が100で、知能偏差値は中心値が50である。

| ISS | 80 | 75 | 70 | 65 | 60 | 55 | 50 | 45 | 40 | 35 | 30 | 25 | 20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIQ | 145 | 138 | 130 | 123 | 115 | 108 | 100 | 93 | 85 | 78 | 70 | 63 | 55 |

簡単に換算するには、標準偏差15の場合、

- ISS × 1.5 + 25 = DIQ

とすればよい。

精神(知能)年齢

前述の精神年齢をそのまま使用して、IQを出さずに生活年齢と併記して表示する方法。IQは生活年齢を基準として相対的な知能の高低を表示する方法であるため、発達の遅れ・進みの度合いが分かりやすいが、絶対値でないため感覚的に理解しにくい。しかし、精神年齢で表示すれば、14歳未満の場合は感覚的に理解しやすくなる。なお、成人の場合は精神年齢での表示は適しない。

知能段階点

知能を5段階ないし7段階に分けて表示する方法。あまり精密な結果を出さない方が良い場合などに用いられる。ウェクスラー式とビネー式では分類基準が異なる。

|

|

パーセンタイル

「知能百分段階点」ともいう。その知能水準が、最下位からどの程度の位置に存在するかを表したもの。一般人100人の集団のうち、下から何番目かという意味だと考えても良い。たとえば「40パーセンタイル」とは、100人のうち下から40番目に位置し、下表ではDIQ97に相当するものである。たとえば、DIQ108以上の人は、下表では70パーセンタイルであり、100人中30人存在することになるが、DIQ130以上の人は、下表では98パーセンタイルであり、100人中2人しか存在しないことになる。ただし、従来のIQではこの表は当てはまらない。

| パーセンタイル | 0.1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 90 | 96 | 97 | 98 | 99 | 99.9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIQ | 54 | 66 | 70 | 72 | 74 | 81 | 88 | 93 | 97 | 100 | 104 | 108 | 113 | 120 | 127 | 129 | 130 | 135 | 146 |

発達指数

発達検査などの場合はIQの代わりに「発達指数 (DQ)」であらわす場合も多い。この場合は、知能面以外にも、歩行・手作業などの運動面、着衣・飲食などの日常生活面、ままごとなどの対人関係面の発達も重視された数値となる。発達検査は低年齢対象のものが多いため、発達指数はIQよりも低年齢で多用される。

遺伝と環境

環境的要因と遺伝的要因は、IQを決定する上で役割を果たす。これらの相対的重要性は、多くの研究と議論の対象となってきた[121]。

遺伝率

アメリカ心理学会の報告書によると、IQの遺伝率の一般的な数値は、子供の場合は0.45であり、後期青年期および成人では約0.75まで上昇する[15]。乳児期のg因子の遺伝率は0.2程度、中年期は0.4程度、成人期では0.9までになる[122][123]。1つの説明は、異なる遺伝子を持つ人々は、異なる環境を求めるなどして、それらの遺伝子の効果を強化する傾向があるというものである[15][124]。

共有された家族環境

家族のメンバーは環境の側面を共有している(例えば、家庭の特徴など)。この共有された家族環境は、子供の頃のIQの変動の0.25~0.35を説明する。後期青年期までには、かなり低くなる(一部の研究ではゼロ)。他のいくつかの心理的特性についても同様の効果がある。これらの研究では、虐待家庭のような極端な環境の影響については調べられていない[15][125][126][127]。

共有されていない家族環境と家族以外の環境

親は子供を違った方法で扱うが、そのような異なる扱いは、共有されていない環境の影響のごく一部しか説明できない。1つの示唆は、子供たちが異なる遺伝子のために同じ環境に異なる反応を示すというものである。より可能性の高い影響は、仲間や家族以外の他の経験の影響かもしれない[15][126]。

個別の遺伝子

ヒトの17,000以上の遺伝子のうち、非常に大きな割合が脳の発達と機能に影響を及ぼすと考えられている[128]。多くの個別の遺伝子がIQと関連していることが報告されているが、強い効果を示すものはない。DearyとColleagues(2009)は、IQに対する強力な単一遺伝子の効果の発見は複製されていないと報告している[129]。成人と子供の通常の知的差異と遺伝子の関連性に関する最近の発見は、どの遺伝子も弱い効果しかないことを示し続けている[130][131]。

2017年に約78,000人の被験者を対象に行われたメタアナリシスでは、知能に関連する52の遺伝子が特定された[132]。FNBP1Lは、成人と子供の両方の知能に最も関連のある単一の遺伝子であると報告されている[133]。

遺伝子-環境相互作用

デビッド・ローは、遺伝的効果と社会経済的地位の相互作用を報告し、社会経済的地位が高い家庭では遺伝率が高いが、社会経済的地位が低い家庭ではかなり低いことを示した[134]。アメリカでは、これは乳児[135]、子供[136]、青年[137]、成人[138]で再現されている。アメリカ以外の国では、遺伝率と社会経済的地位の間に関連性は見られない[139]。一部の効果は、アメリカ以外では符号が逆転する可能性さえある[139][140]。

DickensとFlynn(2001)は、高IQのための遺伝子が環境形成フィードバック・サイクルを開始し、遺伝的効果により賢い子供たちがより刺激的な環境を求めるようになり、それがさらにIQを高めると主張した。Dickensのモデルでは、環境効果は時間とともに減衰するようにモデル化される。このモデルでは、フリン効果は、個人が求めるかどうかにかかわらず、環境刺激の増加によって説明される。著者らは、IQを高めることを目的としたプログラムは、子供たちの認知的に要求される経験を求める意欲を持続的に高めれば、長期的なIQの向上を生み出す可能性が最も高いと示唆している[141][142]。

ジェンセンと『ベル・カーブ』

1969年にアーサー・ジェンセンは「いかにしてIQと成績を向上させられるか」と言う論文で、アメリカにおける人種間の成績の差はそれまで暗黙に仮定されていたように、環境と学習だけの差ではなく、遺伝的差異が関わっている可能性も考慮するべきだと述べて論争を巻き起こした。1994年には『ベル・カーブ』 (The Bell Curve) という845ページの本が、リチャード・ハーンシュタインとチャールズ・マレーによって執筆された。二人は人種間の遺伝的差異は主張しなかったが、やはり知能は環境と学習だけで決定するのではなく個人間に遺伝的差異があり、社会的地位の高い人々と低い人々の間で知能の遺伝的差異が固定するような二分化が起きるのではないか、もしそうなら放置するのは危険ではないかと述べた。知能の遺伝という考えがアプリオリに拒絶されていた時代にあって、彼らの焦点は遺伝的差異を克服する方策であったにもかかわらず、知能が遺伝的に「決定」されると主張して差別を正当化しようとしている、と批判を浴びた。

子供のIQの期待値

アメリカの政治学者であるチャールズ・マレーは、その著書『階級「断絶」社会アメリカ』において、NLSY-79とNLSY-97の学歴別平均IQの数値を用いて、それぞれの学歴別に生まれる子供のIQの期待値を求めた[143]。

| 両親の学歴 | 子供のIQの期待値 |

|---|---|

| 夫婦とも高校中退 | 94 |

| 夫婦とも高校卒業 | 101 |

| 夫婦とも学士号取得 | 109 |

| 夫婦とも修士号取得 | 116 |

| 夫婦とも名門校の学位取得 | 121 |

この子供のIQ期待値自体は遺伝子とは別の問題で、「平均への回帰」という両親のIQと子供のIQの間に経験的に見られる統計的関係のことである[143]。それは関数で表され[注釈 1]、計算が行われると子供のIQの期待値は、両親のIQの中間値から40%母平均に近づくことになる[143]。

ここでマレーは更に次世代の子供達全体の母集団を考察する[143]。「認知能力が群を抜いて高い」子どもたちを、次世代の白人上位5センタイル以内に入る子供たちと定義して、その集団の両親のIQの中間値について次のように述べる。上位5センタイル以内に入る子どもたちの集団の4分の1以上は両親のIQの中間値が125以上、別の約4分の1は両親の中間値が117以上125未満、さらに別の約4分の1は両親の中間値が108以上117未満、残りの約4分の1は両親の中間値が108を下回る。そして白人のIQ分布の下半分に属する両親から生まれてくるケースは、わずか14%となる。

このことは2010年にSATの「英語」と「数学」で700点以上を獲得した高校生の87%は少なくとも両親のどちらかが大学卒であり、56%は少なくとも両親のどちらかが大学院卒だったというデータと符合する[143]。つまり、これらのパーセンテージは、学歴別のIQと両親と子供のIQの相関関係さえあれば、両親の年収や幼児教育の影響、具体的な遺伝と環境の相互作用による影響、試験対策の教育の影響といったものが不明であっても、かなり近いところまで予測が可能である。

生活環境

IQは、生活環境によって大きく変わるとされている。

イギリスでは運河時代(1760年代から1830年代)になると運河で働く船員の多くが、家賃や利便性の問題から家族と共にナロウボートで暮らすようになっており、1923年には船上で生活する子供を対象とした研究が行われた。この研究では学校出席率は全日数の5%で、両親が非識字の場合が多い。先天的なもので文化や環境の影響をうけにくいと考えられていたレーヴン漸進的マトリクスによる流動性知能の検査でも、これらの76人の子供の知能を測ったところ、平均IQは69.6であった。なお、4–6歳では平均IQは90、12–22歳では平均IQは60であり、成長とともに知能の伸びが低くなっている。これは流動性知能と呼ばれるものも、教育の有無が大きく影響している事を示している[144]。

なお、生活環境のみならず検査時の環境や体調によっても大きく変化するが、これは他の検査でも同様であるため「心理検査」で詳述している。

- 僻地・離島

- 僻地の生活者も平均IQは低いとされる。1932年の研究では、アメリカのワシントンD.C.西部のブルーリッジ山脈に住む子供を対象に知能検査をしたところ、山麓にある村の子供のIQは76–118だったが、山間部の子供のIQは60–84だった。また運河船の例と同じように、年齢が高いほどIQが低くなっている[144]。

- また、離島の児童も平均IQは低いとされる。広島大学の武村一郎らによる1965年の研究では、瀬戸内海の人口7千人の島の小学生152人に対して田中ビネー知能検査を実施したところ、男子の平均IQは92、女子の平均IQは80であった。なお、IQ75以下は22%と著しく多かったが、本土の特殊学級の知的障害児との比較では、知能検査のうち学習経験に左右される検査問題では、離島のIQ75以下の児童は低年齢で正答率が低く、高年齢で正答率が高いという特徴があり、一般的な知的障害児とは違いがあった。この研究グループでは、この現象を「離島性仮性知的障害」と名づけている[144]。

- 気温

- カリフォルニア大学ロサンゼルス校ラスキン公共政策大学院の研究者 JISUNG PARK の研究で、2001年から2014年までの13年間、1000万人のアメリカ人学生に行われたPSAT試験の追跡調査が行われた。その結果、気温が高い年の試験結果が悪くなる傾向がみられた。とくに空調の恩恵を受けられない貧困家庭などに大きな影響がみられた[145]。

介入

一般に、以下に述べるような教育的介入は、IQに短期的な効果を示してきたが、長期的なフォローアップがないことが多い。例えば、アメリカでは、ヘッドスタート・プログラムのような非常に大規模な介入プログラムは、IQスコアの持続的な向上をもたらしていない。生徒が標準化されたテストのスコアを上げても、記憶力、注意力、速度などの認知能力が必ずしも向上するわけではない[146]。アベセダリアン・プロジェクトのようなより集中的だがはるかに小規模なプロジェクトでは、IQよりも社会経済的地位の変数に対して、持続的な効果が報告されている[15]。

最近の研究では、ワーキングメモリを使用するトレーニングがIQを高める可能性があることが示されている。ミシガン大学とベルン大学のチームが2008年4月に発表した若年成人を対象とした研究は、特別に設計されたワーキングメモリトレーニングから流動性知能への転移の可能性を支持している[147]。提案された転移の性質、程度、期間を決定するには、さらなる研究が必要である。他の疑問点の中でも、研究で使用されたマトリックス検査以外の他の種類の流動性知能検査にも結果が拡張されるかどうか、もしそうなら、トレーニング後に流動性知能の尺度が教育的および職業的達成との相関を維持するのか、それとも他の課題のパフォーマンスを予測するための流動性知能の価値が変化するのかを見極める必要がある。また、トレーニングが長期間持続するかどうかも不明である[148]。

音楽

子供の頃の音楽トレーニングは、平均以上のIQと相関がある[149][150]。しかし、10,500組の双生児を対象とした研究では、IQへの影響は見られず、相関は遺伝的交絡因子によるものであることが示唆された[151]。あるメタアナリシスでは、「音楽トレーニングは、子供や若年青年の認知スキルや学習スキルを確実に高めるものではなく、以前の肯定的な発見は交絡変数によるものであった可能性が高い」と結論付けている[152]。

クラシック音楽を聴くとIQが上がると一般的に考えられている。しかし、複数の再現実験により、これは せいぜい短期的な効果(10~15分以上持続しない)であり、IQの増加とは関係ないことが示されている[153][154]。

脳の解剖学

ヒトの知能には、脳重量と体重の比率、脳の異なる部位のサイズ、形状、活動レベルなど、いくつかの神経生理学的要因が関連している。IQに影響を与える可能性のある特徴として、前頭葉のサイズと形状、前頭葉の血液と化学的活動の量、脳の灰白質の総量、皮質の全体的な厚さ、ブドウ糖代謝率などがある[155]。

健康

健康は、IQ検査のスコアやその他の認知能力の尺度における差を理解する上で重要である。特に妊娠中や幼少期に起こると、脳が成長しており、血液脳関門の効果が弱いため、いくつかの要因が重大な認知障害につながる可能性がある。このような障害は時に永続的なこともあれば、時に後の成長によって部分的または全面的に補償されることもある[156]。

2010年頃以降、エッピッヒ、ハッセル、マッケンジーに乳幼児や就学前の子供たち、およびこれらの子供たちの母親において、IQスコアと感染症の間に非常に密接で一貫した関連性があることを発見した[157]。彼らは、感染症と闘うことが子供の代謝に負担をかけ、脳の完全な発達を妨げていると推測した。ハッセルは、これが集団のIQを決定する上で最も重要な要因であると仮定した。しかし、彼らはまた、その後の良好な栄養と定期的な質の高い学校教育などの要因が、ある程度は早期の悪影響を相殺できることも発見した。

先進国は、認知機能に影響を与えることが知られている栄養素や毒素に関して、いくつかの健康政策を実施してきた。これには、特定の食品の強化を義務付ける法律[158]や、汚染物質(鉛、水銀、有機塩素化合物など)の安全レベルを定める法律が含まれる。栄養の改善や一般的な公共政策の改善は、IQの上昇に関与してきた[159]。

認知疫学は、知能検査のスコアと健康の関連性を調べる研究分野である。この分野の研究者は、早期に測定された知能が、後の健康と死亡率の差を予測する重要な指標であると主張している[14]。

高いIQは、脳に多くの刺激が行われることから、気分障害や不安障害などの精神疾患イベントが起きやすい[160]。IQ130以上のギフテッドにアンケートをしたところ、約90%が生きづらさを感じていた[161]。

知能が高いほど孤独でいる時間に幸福感を得る傾向がある[162][163]。

社会的相関関係

学校での成績

アメリカ心理学会の報告書『知能:既知のことと未知のこと』は、研究が行われたあらゆる場所で、知能検査で高得点を取る子供は、得点の低い子供に比べて学校で教えられることをより多く学ぶ傾向があると述べている。IQスコアと成績の相関は約0.50である。これは、説明された分散が25%であることを意味する。良い成績を取ることは、IQ以外にも「忍耐力、学校への興味、勉強する意欲」など、多くの要因に左右される(p.81)[15]。

IQスコアと学校の成績の相関は、使用されるIQ測定に依存することが分かっている。大学生の場合、WAIS-Rで測定された言語性IQは、最後の60時間(単位)の成績平均値(GPA)と有意に相関する(0.53)ことが分かっている。対照的に、同じ研究での動作性IQと同じGPAとの相関は0.22に過ぎなかった[164]。

教育適性のいくつかの尺度は、IQ検査と高い相関がある – 例えば、Frey & Detterman (2004)は、g(一般知能因子)とSATのスコアの間に0.82の相関を報告している[165]。また、別の研究では、gとGCSEのスコアの間に0.81の相関があり、説明された分散は「数学で58.6%、英語で48%、美術・デザインで18.1%」の範囲であることが分かった[166]。

仕事の成績

シュミットとハンターによると、「その仕事の経験のない従業員を雇用する場合、将来の業績を予測する最も有効な指標は一般的な精神能力である」[20]。仕事の成績の予測因子としてのIQの妥当性は、これまでに研究されたすべての仕事でゼロを上回っているが、仕事の種類や研究によって異なり、0.2から0.6の範囲である[167]。測定方法の信頼性が低いことを制御すると、相関はより高くなった[15]。IQは推論とより強く相関し、運動機能とはそれほど相関しないが[168]、IQ検査のスコアはあらゆる職業のパフォーマンス評価を予測する[20]。

しかし、高度な資格を必要とする活動(研究、管理)では、低いIQスコアが適切なパフォーマンスの障壁となる可能性が高く、一方、最小限のスキルを必要とする活動では、運動能力(手作業の強さ、速度、持久力、協調性)がパフォーマンスに影響を与える可能性が高い[20]。学界の一般的な見解は、高いIQが仕事のパフォーマンスを媒介するのは、主に仕事に関連する知識をより迅速に習得することによるというものである。この見解は、Byington & Felps(2010)によって異議を唱えられた。彼らは、「IQを反映した検査の現在の適用では、高いIQスコアを持つ個人が、より多くの発達資源にアクセスできるようになり、時間とともに追加の能力を獲得し、最終的により良い仕事ができるようになる」と主張した[169]。

より新しい研究では、仕事のパフォーマンスに対するIQの影響は大幅に過大評価されていることが分かっている。現在、仕事のパフォーマンスとIQの相関は、信頼性の低さと範囲制限を修正して約0.23と推定されている[170][171]。

IQと仕事のパフォーマンスの関連性における因果関係を確立するために、WatkinsらのThe longitudinal studiesは、IQは将来の学業成績に因果的な影響を及ぼすが、学業成績は将来のIQスコアに実質的な影響を及ぼさないことを示唆している[172]。Treena Eileen RohdeとLee Anne Thompsonは、一般的な認知能力は学業成績を予測するが、特定の能力スコアは予測しないと述べている。ただし、一般的な認知能力の影響を超えて、処理速度と空間能力がSATの数学のパフォーマンスを予測する[173]。

しかし、大規模な縦断研究は、IQの増加がすべてのIQレベルでのパフォーマンスの向上につながることを示している。つまり、能力と仕事のパフォーマンスは、すべてのIQレベルで単調に結びついている[174][175]。

収入

「経済的な観点から見ると、IQスコアは逓減的な価値を持つ何かを測定しているようだ」ということと、「十分な量を持つことは重要だが、たくさん持っていてもそれほど多くのものを買うことはできない」ということが示唆されている[176][177]。

IQから富への結びつきは、IQから仕事のパフォーマンスへの結びつきよりもはるかに弱い。いくつかの研究は、IQが純資産とは無関係であることを示唆している[178][179]。アメリカ心理学会の1995年の報告書『知能:既知と未知』は、IQスコアは社会的地位の分散の約4分の1、収入の分散の6分の1を説明すると述べている。親の社会経済的地位を統計的にコントロールすると、この予測力の約4分の1がなくなる。心理測定的知能は、社会的成果に影響を与える多くの要因の1つに過ぎないようである[15]。チャールズ・マレー(1998)は、家庭環境とは独立したIQの収入への実質的な影響を示した[180]。メタ分析では、Strenze(2006)が文献の多くをレビューし、IQと収入の相関を約0.23と推定した[181]。

一部の研究は、多くの研究が、ピークの収入能力や教育レベルにすら達していない若い成人に基づいているため、IQが収入の変動の6分の1しか説明していないと主張している。g因子の568ページで、アーサー・ジェンセンは、IQと収入の相関は平均で中程度の0.4(分散の6分の1または16%)だが、年齢とともに関係は強くなり、人々が最大のキャリアの可能性に達する中年でピークに達すると述べている。『A Question of Intelligence』の中で、ダニエル・セリグマンは、IQと収入の相関を0.5(分散の25%)と述べている。

2002年の研究[182]では、IQ以外の要因が収入に与える影響についてさらに検討し、個人の居住地、相続された富、人種、学歴は、IQよりも収入を決定する上で重要な要因であると結論付けた。

犯罪

アメリカ心理学会の1995年の報告書『インテリジェンス:既知と未知』では、IQと犯罪の相関は-0.2であると述べられている。この関連性は一般的に小さく、適切な共変量を制御した後に消失または大幅に減少しやすく、典型的な社会学的相関よりもはるかに小さいと考えられている[183]。デンマークの大規模なサンプルでは、IQスコアと少年犯罪件数の相関は-0.19であった。社会階級をコントロールすると、相関は-0.17に低下した。相関が0.20ということは、説明された分散が全分散の4%を占めることを意味する。心理測定的能力と社会的成果の因果関係は間接的なものかもしれない。学業成績の悪い子供は疎外感を感じるかもしれない。その結果、彼らは他の成績の良い子供に比べて、非行に走る可能性が高くなるかもしれない[15]。

アーサー・ジェンセンは、『g因子』(1998年)の中で、人種に関係なく、IQが70から90の人は、この範囲より下または上のIQの人よりも犯罪率が高く、ピークの範囲は80から90の間であることを示すデータを引用した。

2009年の『犯罪相関のハンドブック』は、レビューにおいて、特に持続的な重大犯罪者の場合、犯罪者と一般人口とを分けるのは約8IQポイント、つまり0.5SDであることが分かったと述べている。これは単に「バカだけがつかまる」ことを反映しているだけだと示唆されているが、IQと自己申告の犯罪との間にも同様に負の関係がある。行為障害の子供たちが仲間よりもIQが低いことは、この理論を「強く支持」している[184]。

米国の郡レベルのIQと米国の郡レベルの犯罪率の関係を調べた研究では、平均IQが高いほど、財産犯罪、侵入窃盗、窃盗率、自動車盗難、暴力犯罪、強盗、加重暴行のレベルがわずかに低いことが分かった。これらの結果は、「人種、貧困、その他の郡の社会的不利益の影響を捉えた集中的不利益の尺度では交絡されなかった」[185]。しかし、この研究は、青年の健康に関する全米での長期調査の推定値を回答者の郡に外挿したものであり、このデータセットは州または郡レベルで代表的であるように設計されていないため、一般化できない可能性がある[186]。

また、IQの効果は社会経済的地位に大きく依存しており、多くの方法論的考慮事項が関与しているため、簡単に制御できないことも示されている[187]。実際、この小さな関係性は幸福度、物質乱用、その他の交絡因子によって媒介されているという証拠があり、単純な因果関係の解釈を妨げている[188]。最近のメタアナリシスでは、この関係は貧困などのリスクの高い集団でのみ直接的な影響なしに観察されるが、因果関係の解釈はないことが示されている[189]。全国的に代表的な縦断研究では、この関係は学校のパフォーマンスによって完全に媒介されていることが示されている[190]。

日本の新受刑者の知能指数の割合(2012年)

日本の刑務所の場合、受刑者となったものはまず知能指数の検査を受ける必要があり、その結果は法務省が発行する矯正統計年報に公表される。2012年の数字では、新受刑者総数2万4780人のうち5214人、全体の21%が知能指数69以下の受刑者ということになり、さらに測定不能者も839人を加えると、全体の約4分の1の受刑者が、知的障害者として認定される人たちである[191]。

日本の受刑者の知能指数は、昭和40年にも調査がなされていて以下の表のようになっている[192]。男女ともに知能指数の高いものはきわめて少なく、特に女子の受刑者は男子受刑者に比較して知能指数の低いものが多く、知能指数60から89のものが半数以上であり、知能指数59以下のものも27%に達している。

| 知能指数 | 女子 | 男子 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 人員 | % | 人員 | % | |

| 130以上 | ー | ー | 107 | 0.2 |

| 120 - 129 | ー | ー | 414 | 0.8 |

| 110 - 119 | 9 | 0.8 | 1,732 | 3.5 |

| 100 - 109 | 43 | 3.8 | 4,937 | 10.0 |

| 90 - 99 | 108 | 9.5 | 9,688 | 19.7 |

| 80 - 89 | 190 | 16.8 | 12,233 | 24.8 |

| 70 - 79 | 258 | 22.8 | 9,463 | 19.2 |

| 60 - 69 | 217 | 19.1 | 6,221 | 12.6 |

| 50 - 59 | 170 | 15.0 | 2,687 | 5.5 |

| 49以下 | 138 | 12.2 | 1,791 | 3.7 |

| 総数 | 1,133 | 100.0 | 49,273 | 100.0 |

また、法務省司法法制部は、矯正統計調査を発表しており、その中には「新受刑者の罪名別 知能指数」という統計表を公開している[193]。

| 罪名 | 総数 | 49以下 | 50 - 59 | 60 - 69 | 70 - 79 | 80 - 89 | 90 - 99 | 100 - 109 | 110 - 119 | 120以上 | テスト不能 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 平成17年 | 総数 | 32,789 | 1,351 | 1,937 | 4,102 | 6,998 | 8,574 | 5,670 | 1,783 | 287 | 52 | 2,035 |

| 男 | 30,607 | 1,266 | 1,806 | 3,868 | 6,590 | 8,042 | 5,316 | 1,689 | 269 | 51 | 1,710 | |

| 女 | 2,182 | 85 | 131 | 234 | 408 | 532 | 354 | 94 | 18 | 1 | 325 | |

| 平成18年 | 総数 | 33,032 | 1,349 | 1,974 | 4,240 | 7,501 | 8,305 | 5,647 | 1,883 | 303 | 65 | 1,765 |

| 男 | 30,699 | 1,255 | 1,853 | 3,988 | 7,024 | 7,742 | 5,301 | 1,775 | 286 | 64 | 1,411 | |

| 女 | 2,333 | 94 | 121 | 252 | 477 | 563 | 346 | 108 | 17 | 1 | 354 | |

| 平成19年 | 総数 | 30,450 | 1,233 | 1,702 | 3,785 | 7,265 | 7,656 | 5,042 | 1,810 | 293 | 59 | 1,605 |

| 男 | 28,272 | 1,135 | 1,597 | 3,523 | 6,684 | 7,148 | 4,734 | 1,709 | 278 | 55 | 1,409 | |

| 女 | 2,178 | 98 | 105 | 262 | 581 | 508 | 308 | 101 | 15 | 4 | 196 | |

| 平成20年 | 総数 | 28,963 | 1,232 | 1,742 | 3,729 | 6,726 | 7,039 | 4,970 | 1,757 | 288 | 53 | 1,427 |

| 男 | 26,768 | 1,126 | 1,598 | 3,463 | 6,211 | 6,516 | 4,633 | 1,671 | 273 | 52 | 1,225 | |

| 女 | 2,195 | 106 | 144 | 266 | 515 | 523 | 337 | 86 | 15 | 1 | 202 | |

| 平成21年 | 総数 | 28,293 | 1,176 | 1,792 | 3,552 | 6,078 | 7,296 | 4,984 | 1,846 | 265 | 41 | 1,263 |

| 男 | 26,123 | 1,071 | 1,636 | 3,285 | 5,606 | 6,757 | 4,631 | 1,753 | 254 | 41 | 1,089 | |

| 女 | 2,170 | 105 | 156 | 267 | 472 | 539 | 353 | 93 | 11 | - | 174 | |

| (うち,少年受刑者) | 男 | 54 | 1 | - | 1 | 9 | 17 | 13 | 5 | 2 | - | 6 |

| 刑法犯 | 男 | 17,783 | 906 | 1,321 | 2,444 | 3,720 | 4,312 | 2,950 | 1,161 | 163 | 24 | 782 |

| 女 | 1,245 | 93 | 126 | 181 | 250 | 276 | 169 | 47 | 5 | - | 98 | |

| 公務執行妨害 | 男 | 138 | 5 | 10 | 23 | 32 | 39 | 19 | 6 | - | 1 | 3 |

| 女 | 2 | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 逃走 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 犯人蔵匿・証拠隠滅 | 男 | 6 | - | - | 1 | 2 | 2 | - | 1 | - | - | - |

| 女 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 騒乱 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 放火 | 男 | 170 | 14 | 19 | 25 | 42 | 33 | 24 | 5 | - | - | 8 |

| 女 | 28 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 5 | - | - | - | 1 | |

| 住居侵入 | 男 | 396 | 16 | 38 | 63 | 74 | 100 | 57 | 24 | 4 | - | 20 |

| 女 | 4 | - | - | - | 2 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | |

| 通貨偽造 | 男 | 13 | - | 1 | 3 | - | 5 | 2 | - | - | - | 2 |

| 女 | 2 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | |

| 文書偽造・有価証券偽造・支払用カード電磁的記録関係・印章偽造 | 男 | 236 | 4 | 5 | 24 | 45 | 63 | 39 | 30 | 2 | - | 24 |

| 女 | 29 | - | 1 | 6 | 9 | 5 | 4 | - | - | - | 4 | |

| 偽証・虚偽告訴 | 男 | 2 | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| わいせつ・わいせつ文書頒布等 | 男 | 151 | 4 | 6 | 16 | 31 | 46 | 28 | 13 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| 強制わいせつ・同致死傷 | 男 | 344 | 18 | 24 | 37 | 41 | 85 | 75 | 45 | 4 | 1 | 14 |

| 女 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 強姦・同致死傷 | 男 | 385 | 15 | 13 | 24 | 67 | 93 | 104 | 45 | 8 | - | 16 |

| 賭博・富くじ | 男 | 32 | - | 1 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 13 | 4 | - | - | 2 |

| 贈収賄 | 男 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 殺人 | 男 | 335 | 9 | 19 | 44 | 71 | 76 | 64 | 22 | 3 | 1 | 26 |

| 女 | 80 | 2 | 6 | 10 | 19 | 23 | 11 | 1 | 1 | - | 7 | |

| 傷害 | 男 | 1,329 | 40 | 66 | 164 | 302 | 345 | 269 | 94 | 13 | 1 | 35 |

| 女 | 23 | - | 1 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 5 | - | - | - | 3 | |

| 傷害致死 | 男 | 112 | 3 | 7 | 11 | 27 | 26 | 24 | 8 | 2 | - | 4 |

| 女 | 14 | - | - | 1 | 3 | 5 | 5 | - | - | - | - | |

| 暴行 | 男 | 150 | 7 | 15 | 29 | 29 | 38 | 18 | 8 | - | - | 6 |

| 女 | 3 | - | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 危険運転致死傷 | 男 | 60 | 1 | - | 6 | 10 | 22 | 13 | 4 | - | - | 4 |

| 女 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 業務上過失致死傷 | 男 | 52 | - | - | 10 | 11 | 15 | 10 | - | 3 | - | 3 |

| 女 | 4 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | |

| 重過失致死傷 | 男 | 2 | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 自動車運転過失致死傷 | 男 | 268 | 4 | 13 | 33 | 53 | 71 | 56 | 21 | 3 | - | 14 |

| 女 | 20 | - | - | - | 3 | 5 | 10 | - | - | - | 2 | |

| 脅迫 | 男 | 66 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 13 | 26 | 6 | 5 | 1 | - | 1 |

| 女 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | |

| 略取・誘拐及び人身売買 | 男 | 16 | 2 | 3 | - | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | - | - | 2 |

| 窃盗 | 男 | 8,513 | 605 | 748 | 1,287 | 1,858 | 1,968 | 1,173 | 442 | 64 | 15 | 353 |

| 女 | 780 | 81 | 99 | 123 | 149 | 154 | 82 | 30 | 3 | - | 59 | |

| 強盗 | 男 | 517 | 12 | 37 | 63 | 97 | 127 | 89 | 37 | 12 | 2 | 41 |

| 女 | 14 | - | - | 2 | 5 | 4 | - | 1 | - | - | 2 | |

| 強盗致死傷 | 男 | 466 | 7 | 18 | 38 | 95 | 117 | 108 | 31 | 5 | 1 | 46 |

| 女 | 19 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 1 | - | - | 2 | |

| 強盗強姦・同致死 | 男 | 47 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 11 | 9 | - | - | 8 |

| 詐欺 | 男 | 2,354 | 83 | 162 | 313 | 466 | 584 | 440 | 191 | 25 | 1 | 89 |

| 女 | 164 | 4 | 12 | 20 | 34 | 45 | 32 | 9 | - | - | 8 | |

| 恐喝 | 男 | 479 | 5 | 23 | 59 | 100 | 152 | 93 | 33 | 3 | - | 11 |

| 女 | 9 | - | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | - | - | - | 1 | |

| 横領・背任 | 男 | 375 | 25 | 32 | 52 | 85 | 72 | 66 | 23 | 3 | - | 17 |

| 女 | 30 | - | - | - | 4 | 11 | 6 | 3 | 1 | - | 5 | |

| 盗品等関係 | 男 | 51 | 2 | 6 | 9 | 4 | 14 | 9 | 3 | 1 | - | 3 |

| 女 | 3 | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | |

| 決闘罪に関する件 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 爆発物取締罰則 | 男 | 10 | - | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| 暴力行為等処罰に関する法律 | 男 | 230 | 12 | 14 | 36 | 53 | 60 | 41 | 11 | 1 | - | 2 |

| 女 | 3 | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | |

| その他の刑法犯 | 男 | 472 | 9 | 29 | 57 | 99 | 114 | 94 | 43 | 3 | - | 24 |

| 女 | 10 | 1 | - | 4 | 2 | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | |

| 特別法犯 | 男 | 8,340 | 165 | 315 | 841 | 1,886 | 2,445 | 1,681 | 592 | 91 | 17 | 307 |

| 女 | 925 | 12 | 30 | 86 | 222 | 263 | 184 | 46 | 6 | - | 76 | |

| 公職選挙法 | 男 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| 軽犯罪法 | 男 | 11 | 1 | - | 2 | 3 | - | - | 1 | - | - | 4 |

| 銃砲刀剣類所持等取締法 | 男 | 161 | 13 | 11 | 24 | 29 | 40 | 24 | 8 | 1 | - | 11 |

| 女 | 3 | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | |

| 売春防止法 | 男 | 27 | - | - | 1 | 3 | 11 | 10 | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| 女 | 12 | - | - | 4 | 3 | 4 | - | - | - | - | 1 | |

| 児童福祉法 | 男 | 74 | - | 2 | 6 | 9 | 20 | 20 | 8 | 2 | - | 7 |

| 麻薬及び向精神薬取締法 | 男 | 51 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 11 | 8 | 14 | 2 | 2 | - | 9 |

| 女 | 6 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | |

| 覚せい剤取締法 | 男 | 5,297 | 60 | 134 | 513 | 1,211 | 1,654 | 1,126 | 388 | 59 | 10 | 142 |

| 女 | 789 | 9 | 27 | 70 | 187 | 234 | 165 | 41 | 6 | - | 50 | |

| 職業安定法 | 男 | 2 | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 道路交通法 | 男 | 1,508 | 60 | 99 | 178 | 371 | 403 | 258 | 71 | 5 | 2 | 61 |

| 女 | 55 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 18 | 10 | 11 | 3 | - | - | 8 | |

| 出入国管理及び難民認定法 | 男 | 95 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 20 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 31 |

| 女 | 30 | - | 1 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 1 | - | - | 13 | |

| その他の特別法犯 | 男 | 1,113 | 19 | 57 | 104 | 228 | 303 | 224 | 112 | 21 | 4 | 41 |

| 女 | 30 | 1 | - | 5 | 7 | 8 | 5 | 1 | - | - | 3 |

健康と死亡率

スコットランドで行われた複数の研究では、早期の高いIQは、後の人生における死亡率と罹患率の低下に関連していることが分かっている[194][195]。

学歴との関係

これらのカテゴリー内およびカテゴリー間には、かなりのばらつきと重複がある。高いIQの人は、すべての教育レベルと職業カテゴリーに見られる。最も大きな差は低いIQで生じ、90未満のスコアを持つ大学卒業者や専門職はごくまれにしかいない[30]。

| 業績 | IQ | テスト/研究 | 年 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 医学博士、法学博士、哲学博士 | 125 | WAIS-R | 1987 |

| 大学卒業生 | 112 | KAIT | 2000 |

| K-BIT | 1992 | ||

| 115 | WAIS-R | ||

| 大学1-3年 | 104 | KAIT | |

| K-BIT | |||

| 105–110 | WAIS-R | ||

| 事務職および販売職 | 100–105 | ||

| 高校卒業、熟練工(電気技師、家具職人など) | 100 | KAIT | |

| WAIS-R | |||

| 97 | K-BIT | ||

| 高校1-3年(9-11年の学校教育修了) | 94 | KAIT | |

| 90 | K-BIT | ||

| 95 | WAIS-R | ||

| 半熟練工(トラック運転手、工場労働者など) | 90–95 | ||

| 小学校卒業(8年生修了) | 90 | ||

| 小学校中退(0-7年の学校教育修了) | 80–85 | ||

| 高校に進学する可能性が50/50 | 75 |

また、アメリカの政治学者であるチャールズ・マレーは、米国青年パネル調査(National Longitudianl Survey of Youth,NLSY)の調査対象である1979年のコーホート[111]と1997年のコーホート[198]のデータを基にして、対象者が25歳に達した年の白人の学歴別平均IQの表を作成した[199]。

| 以下の学位まで取得した人々の平均IQ | 1982-89 | 2005-09 |

|---|---|---|

| 学位なし | 88 | 87 |

| 高校卒業証書あるいは一般教育修了検定(GED) | 99 | 99 |

| 準学士 | 105 | 104 |

| 学士 | 113 | 113 |

| 修士 | 117 | 117 |

| 博士(PhD,LDD,MD,DDS) | 126 | 124 |

職業との関係

IQは職業上の成功に必要とされる数多くある資質の中の一つに過ぎないが、知能検査と勤務成績との相関が心理テスト関係では最大(0.51)である[200][201]など、重要な資質であることには変わりない。社会学者のスティーブン・ゴールドバーグはNFL(プロフットボール・リーグ)の比喩を用いて説明する[202]。NFLの選手の攻めのタックルに重い体重が必要とされるように、知的職業やクリエイティブな仕事、大組織の管理職には高い知能が必要とされる。体重が重ければいいタックルを決められるとは限らないが、選手としてのチャンスを掴むためには136kg以上あったほうがいい。同じように、弁護士、脚本家、生化学者などの場合も、IQが高いからと言って成功するとは限らないが、IQがあまり高くないと、これらの職業での成功はおぼつかないのである。

また、米軍はIQ85未満の志願者を採用していない[203]。

職業集団とWAIS-Rの全検査IQ

レイノルズ、チャスティン、カウフマン、マクリーンによると、アメリカのWAIS-R標準化集団20-54歳では、下記の表に示すように職業とIQとの明確な関係があった[204]。

| 職業集団 | 全検査IQの平均 |

|---|---|

| 専門的・技術的職業(医者、弁護士) | 112.4 |

| 経営者・役員(事務職員、販売員) | 103.6 |

| 熟練労働者(職人、職長) | 100.7 |

| 半熟練労働者(サービス業、農業) | 92.3 |

| 非熟練労働者(肉体労働者、農場労働者) | 87.1 |

職業カテゴリー別のg因子負荷量とIQ

アメリカの政治学者であるチャールズ・マレーは、労働統計局(BLS)の1990年の職業分類を基にして、職業を8つにカテゴリーに分類した[206]。なお、総合社会調査(GSS)と米国パネル調査(NLS)のデータは、1960年、1970年、1980年、2000年の分類を、BLSの1990年の分類に変換されている[206]。

- 地位の高い専門的職業及びシンボリック・アナリスト的職業

- 医師、弁護士、建築士、エンジニア、大学教職員、科学者、テレビ・映画・出版・ニュース報道のコンテンツ制作者など

- 管理職

- 企業、政府機関、教育機関、財団、非営利団体、公共団体等の経営管理職

- 中級ホワイトカラー職

- 保険業者、バイヤー、事務官、検査官、不動産業者、広告販売業、人事専門家など

- 高度な技術を要する専門職

- K-12の教員、警察官、看護師、薬剤師、理学療法士、科学・エンジニアリング部門の専門技術者など

- ブルーカラー専門職

- 農場のオーナー・管理者、電気技師、配管工、工具・金型製作者、工作機械熟練工、家具職人など

- 技術を要するその他のブルーカラー職

- 機械工、重機オペレーター、修理工、料理人、溶接工、壁紙貼り職人、ガラス工、石油採掘者など

- 下級ホワイトカラー職

- 文書係、タイピスト、書類配達係、銀行の出納係、受付係など

- 高度な技術を必要としないサービスおよびブルーカラー職

- レジ係、警備員、炊事従業員、病院の用務員、荷物運搬人、駐車場係、運転手、建設作業員など

マレーは上記の職業カテゴリーの順位付けを行った。職業の順位付けを行うにあたって、職業威信尺度や教育水準による職業の順位付けでは妥当性が得られないとして、計量心理学者のアール・ハントとタラ・マドゥエスタの研究を応用し、職業に関する「g因子負荷量」(g-loading)を職業別の認知能力要件の尺度として用いた[207]。そして、NLSY-79[111]の白人をサンプルにして、このコーホートの全員が30代後半から40代半ばであったデータから、職業カテゴリー別の平均g因子負荷量と平均IQの表を作成した[208]。

| 職業カテゴリー | 平均g因子負荷量 | 平均IQ |

|---|---|---|

| 地位の高い専門的職業 | 120 | 117 |

| 管理職 | 116 | 107 |

| 中級ホワイトカラー職 | 111 | 107 |

| 高度な技術を要する専門職 | 107 | 109 |

| ブルーカラー専門職 | 109 | 100 |

| 下級ホワイトカラー職 | 92 | 103 |

| 技術を要するその他のブルーカラー職 | 89 | 98 |

| 高度な技術を必要としないサービスおよびブルーカラー職 | 83 | 94 |

その他

| 業績 | IQ | テスト/研究 | 年 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 大人は野菜を収穫し、家具を修理できる | 60 | ||

| 大人は家事労働ができる | 50 |

様々な要素との相関

アメリカの進化心理学者のジェフリー・ミラーによると、次に挙げる項目と一般知性が正の相関を示すという[209]。

- 脳全体の大きさ(構造MRIで生きている人を計測した際の大きさ)[210][139][211][212][98]

- 特定の皮質領域の大きさ(外側・内側の前頭前野や高頭頂葉などのサイズ)[139][213][214][215][216]

- 特定の神経化学物質(N-アセチルアスパラギン塩酸など)の脳内濃度[217]

- 子供の時に大脳皮質が最も分厚くなる年齢[218]

- 基本的な感覚運動タスクをこなす速さ(例として点灯したボタンを出来るだけ早く押すタスクなど)[219][220][221]

- 神経繊維がインパルスを腕や脚へ伝達する速さ[222][223]

- 身長[224][225]

- 顔や体の左右対称[226][227][228][229][98][230]

- 身体的な健康と寿命[231][232][219][233][234][235]

- 男性の場合、精液の質(精子の数、濃度、運動性)[236]

- 心の健康(統合失調症。外傷後ストレスその他の精神機能障害の発症率は、「知性が高いほど」低くなる)[237][238][239]

- 恋愛対象としての魅力(少なくとも長期的な関係の場合)[240][241][242][243][244][245][246][247][248]

グループ間の差異

知能研究に関連する最も議論の的となっている問題の1つは、IQスコアが民族集団や人種集団の間で平均的に異なるという観察であり、これらの差は変動し、多くの場合、時間とともに着実に減少している[249]。これらの差の一部が現在も存在していることについては学術的な議論は少ないが、現在の科学的コンセンサスは、これらの差は遺伝的な原因ではなく環境的な原因から生じているというものである[250][251][252]。性別間のIQの差の存在については議論があり、主にどのようなテストを行うかに依存している[253][254]。

人種

「人種」の概念は現代のアメリカの人類学者の間では社会的構築物であるとされているが[255]、人種と知能の関係に関する議論や、人種に沿った遺伝的知能差の主張は、現代の人種概念が初めて導入されて以来、通俗科学と学術研究の両方に登場してきた。このトピックに関する膨大な量の研究にもかかわらず、異なる集団のIQスコアの平均値の差が、それらの集団間の遺伝的差異に起因するという科学的証拠は出ていない[256][257][258]。環境要因が人種間のIQ差を説明し、遺伝的要因ではないという証拠が増えている[219][259][252]。

アメリカ心理学会が1996年に実施した知能に関するタスクフォース調査では、人種間でIQに有意な差があると結論付けている[15]。しかし、ウィリアム・ディケンズとジェームズ・フリンによる2006年の体系的分析では、1972年から2002年の間に、黒人アメリカ人と白人アメリカ人のIQの差が劇的に縮小したことが示され、彼らの言葉を借りれば、「黒人と白人のIQ差の不変性は神話である」ことが示唆された[260]。

人種間の差異の原因を決定する問題は、例えばアラン・S・カウフマン[261]やネイサン・ブロディ[262]によって、「生得か育ちか」の典型的な問題として長々と議論されてきた。バーニー・デブリンのような研究者は、黒人と白人のIQ差が遺伝的影響によるものだと結論付けるには不十分なデータしかないと主張している[263]。ディケンズとフリンは、より積極的に、彼らの結果は遺伝的起源の可能性を反証しており、観察された差は「環境が責任を負っている」と結論付けている[260]。2012年に発表された人間の知能に関する主要な研究者によるレビュー論文でも、これまでの研究文献をレビューした結果、IQの集団差は環境的起源として理解するのが最適であるという同様の結論に達している[264]。最近では、遺伝学者・神経科学者のケビン・ミッチェルが、集団遺伝学の基本原理に基づいて、「大規模で古い集団間の体系的な知能の遺伝的差異」は「本質的に深く信じがたい」と主張している[265]。

ステレオタイプ脅威の影響は、人種集団間のIQテストの成績差の説明として提唱されており[266][267]、文化的差異や教育へのアクセスに関連する問題も指摘されている[268][269]。

性別

長年研究者によって議論されており、数多くの研究が存在する。

一般知能つまり"g"の概念の登場により、多くの研究者は、一般知能には有意な性差はないが[254][270][271]、特定の種類の知能では差があることを発見した[253][271]。したがって、一部のテストバッテリーでは男性の知能がわずかに高く、他のテストバッテリーでは女性の知能が高くなっている[253][271]。特に、言語能力に関連するタスクでは女性被験者の方が優れており[254]、物体の空間的回転に関連するタスクでは男性の方が優れていることが多く、空間能力として分類されることが多い[272]。Hunt (2011)が指摘するように、これらの差は、「男女の一般知能がほぼ等しいにもかかわらず」存在する。

認知能力と脳の大きさの関連について、同様の研究の中で過去最大規模の13,600人以上のデータを使用し2018年に発表された調査では、体格に比例する男女の脳の大きさの違いは認知能力の差には繋がらなかった[48]。他の研究では、女性は男性より脳の皮質が厚くなる傾向が確認されており[273][274][275]、男女間で認知能力に有意な差が見られない事実は、これらの脳の質の違いによる可能性を示している[48][276]。

一部の研究では、社会経済的要因を統制すると、一部の認知テストにおける男性の優位性が最小化されることが示されている[253][270]。他の研究では、特定の領域において、女性のスコアと比較して男性のスコアの変動性がわずかに大きいため、IQ分布の上位と下位で男性が女性をわずかに上回ると結論付けられている[277]。

数学関連のテストにおける男女の成績差の存在については議論があり[278]、数学の成績における平均的な性差に焦点を当てたメタ分析では、男女の成績がほぼ同一であることが分かった[279]。過去数十年間の比較によると、米国では男女の数学の分布上部の差は縮まっており、国によっては分布に男女差は見られない[280]。一部の国では分布の上部で男女比が逆転している場合がある[281]。2008年に発表された調査では、白人系米国人のグループでは数学のスコアの分布は男性のほうが最上部と最下部へ広く、一方アジア系米国人のグループでは分布の最上部で女性の比率が高かった[282]。SATのスコアを比較した調査では、数学のスコア最上位0.01%の女子の比率は80年代には7%であったが、2010年には28%へと変化している。SATの言語科目ではスコア最上位0.01%の男女比は80年代には等しかったが、2010年には女子の比率は60%へと変化していることが発見されている[283]。数学や認知能力の変動に関する研究では、米国では男性のほうが分布が広いことが報告されているが、女性の分布が広い国も報告されており、米国の結果は国や文化を超えて不変でないことが発見された[284]。現在、WAISやWISC-Rなどの一般的なバッテリーを含むほとんどのIQテストは、女性と男性の全体的なスコアに差がないように構成されている[15][285][286]。

時代や文化を超えて普遍的な性質だと考えられてきたこの違いには、社会や文化的な要因も影響することが報告されている[280]。分布の男女差がジェンダーギャップ指数とも比例し、ギャップの小さな国では女性の変動性が増大し、女性の能力分布を広げることが発見された[287][281][288]。

リンとアーウィングはレーヴン漸進的マトリックスにおいて10代前半までは性差はなく、10代後半から男性のスコアが高くなるという報告をしたが[289]、他の研究者達は男女差について矛盾する結果を発見している。ロヤーンの研究では、知能発達の性差はリンとアーウィングの予測よりも非常に小さく、どの年代においても有意差が見られないため実用的見地からの重要性がほとんどないことが判明した[290]。ほとんどの研究では知能の男女差は非常に小さいか全く見られないことが分かっているが、いくつかの調査では一部の国で男性が数ポイントの僅かな優位性を示し、一方で女性が僅かな優位性を示す研究も報告されている[291][292]。成人約1万人を対象としたコロンによる研究では、性差は非常に小さく無視できる程度であり、有意差がないことが報告されている[293]。

公共政策

アメリカ合衆国では、公共の秩序に関する特定の法律や政策において、兵役[294][295]、教育、公的給付[296]、死刑[105]、雇用などの判断に個人のIQが組み込まれている。しかし、1971年のグリッグス対デューク・パワー社事件では、人種的マイノリティに不均衡な影響を与える雇用慣行を最小限に抑えるため、アメリカ合衆国最高裁判所は、職務分析を通じて職務遂行に関連付けられている場合を除き、雇用におけるIQテストの使用を禁止した。国際的には、栄養改善や神経毒性物質の禁止など、特定の公共政策の目標の1つとして、知能の向上または低下の防止が掲げられている。

イギリスでは、1945年から知能検査を組み込んだイレブンプラスが、11歳の時点でどのタイプの学校に進学するかを決定するために使用されてきた。総合制学校の広範な導入以降、この試験の使用は大幅に減少している。

障害者認定

知的障害の診断は、一部IQテストの結果に基づいている。境界知能機能は、知的障害(70以下)ほどではないが、平均以下の認知能力(IQ71~85)の個人の分類である。知的障害の定義は「IQ70未満で社会性に障害があること」であり、この定義で約2%の人が知的障害に該当している[269]。厚生労働省はIQと生活能力をもとに知的障害の程度を分類しており、生活能力が平均的ならばIQ51–70は軽度、36–50は中度、21–35は重度、20以下は最重度となる[297][298]。IQ40未満を測れない検査も多い。

IQ65または75以下の人は知的障害があると認定され、また療育手帳の交付対象となる。50 - 69相当では心理的要因などの理由で、精神障害者保健福祉手帳3級(合併症は除く)の取得もできる。なお70以下の人は理論的には2.27%だが、そのうち知的障害者認定を受けているのは6人ないし7人に1人程度である。実用的かつ正確な方法などで分かることとしては重度な言語の狂いがあることやあまりにも逸脱している文法の狂い等やCT検査で図面的に見ることで分かるケースが圧倒的に多いのでIQだけで判断できることはないという考えも増えてきている。また、DIQを結果表示に用いる知能検査では、IQ40未満が実質的に測定できず、障害者手帳の交付時の診断で齟齬をきたす場合がある。

DSM-Ⅳによれば、精神遅滞の診断には、およそIQ70以下で、現在の適応機能が意思伝達、自己管理、家庭生活、社会的技能等の2つ以上の領域で欠陥か不全があるという条件が必要となっている[299]。

約14%を占めるIQ70-84は境界知能(グレーゾーン)と呼ばれ、知能指数が平均未満であるが知的障害とは見なさない層であるが[278][269]、過去のICD第8版(1965年-1974年)ではIQ70-84の人々は境界線精神遅滞とされていた[269]。

就学時健康診断

就学時健康診断の際にも、知的障害の存在可能性などを調べるために知能検査が行われる。その多くはあまり精密でない簡単な検査だが、一部では健常児と障害児を分離し、統合教育に逆行するものだとして批判されている。なお、2002年の法改正により、知能検査以外の適切な検査を使用することも可能となった。

分類

IQの分類は、IQテストの出版社が、「優秀」や「平均」などのラベルを用いてIQスコアの範囲をさまざまなカテゴリーに指定するために使用している手法である[197]。IQの分類は、歴史的に、他の形態の行動観察に基づいて人間を一般的な能力によって分類しようとする試みが先行していた。これらの他の形態の行動観察は、IQテストに基づく分類の妥当性を検証するために今でも重要である。

高IQ

文献等に現れた正式の知能検査による数値例

- 平均128(ニュルンベルク裁判におけるナチス戦犯21名のウェクスラーベルビュー知能尺度のドイツ語翻訳版による)

- 平均126.5(ケンブリッジ大学の自然科学系の教授会メンバー148人のウェクスラーテストによる。ギブソンとライト 1967年)

- 平均133.7(旧制浪速高等学校尋常科に進学した生徒25人の小学生時代の鈴木ビネーテストによる。鈴木治太郎 1936年)

- 平均112.0(大阪府における中等学校進学者1675名の小学校時代の鈴木ビネーテストによる。同上)

- 平均122.4 標準偏差6.97(富山大学生33人のWAISによる。村上・村上 1981)

- 平均116.8 標準偏差8.1(関西大学生100人の京大NX知能検査による。石川啓 1965)

高IQ団体

IQテストまたは同等のテストで98パーセンタイル(平均より2標準偏差上)以上のスコアを持つ人に会員資格を制限している社会組織があり、その中にはいくつかの国際的な組織もある。国際メンサは、おそらくこの中で最もよく知られている。99.9パーセンタイル(平均より3標準偏差上)の最大の団体は、トリプルナイン・ソサエティである。

脚注

注釈

- ^ マレーは、平均への回帰の大きさを予測しするため、標準的な線形回帰の方程式である次の式を使う。 親子のIQの関係の場合には、 子供のIQの期待値は、。 その父母のIQの中間値は、。 父母のIQの標本平均は、。 子供のIQの標本平均は、。 父母のIQの中間値と子供のIQの標本相関は、。 そして父母のIQの中間値と子供のIQの標本標準偏差は、と である。 これらのパラメーターには、白人の平均IQ103と標準偏差14.5が使用され、平均IQは次の各試験の基準化算定のために実施された標本平均の平均が基にされた。スタンフォード=ビネ知能検査、ウェクスラー成人知能検査、ウェクスラー児童知能検査、そして米軍入隊試験ASVABである。これらのデータセットの平均標準偏差は14.5であり、父母のIQ中間値の分散を計算するにあたっては、(方程式はHumphreys 1978の付録に載っている)夫婦のIQの相関係数を+0.5としたので、白人の標準偏差14.5に対して、父母のIQ中間値の標準偏差期待値は12.6となる。

- ^ 法務省矯正局の調査による。また、女子78人、男子880人は未調査で除外してある。

出典

- ^ Braaten, Ellen B.; Norman, Dennis (1 November 2006). "Intelligence (IQ) Testing". Pediatrics in Review. 27 (11): 403–408. doi:10.1542/pir.27-11-403. ISSN 0191-9601. PMID 17079505. 2020年1月22日閲覧。

- ^ Stern 1914, pp. 70–84 (1914 English translation), pp. 48–58 (1912 original German edition).

- ^ "intelligence quotient (IQ)". Glossary of Important Assessment and Measurement Terms. Philadelphia, PA: National Council on Measurement in Education. 2016. 2017年7月22日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2017年7月1日閲覧。

- ^ a b Gottfredson 2009, pp. 31–32

- ^ Neisser, Ulrich (1997). "Rising Scores on Intelligence Tests". American Scientist. 85 (5): 440–447. Bibcode:1997AmSci..85..440N. 2016年11月4日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2017年12月1日閲覧。

- ^ Hunt 2011, p. 5 "As mental testing expanded to the evaluation of adolescents and adults, however, there was a need for a measure of intelligence that did not depend upon mental age. Accordingly the intelligence quotient (IQ) was developed. ... The narrow definition of IQ is a score on an intelligence test ... where 'average' intelligence, that is the median level of performance on an intelligence test, receives a score of 100, and other scores are assigned so that the scores are distributed normally about 100, with a standard deviation of 15. Some of the implications are that: 1. Approximately two-thirds of all scores lie between 85 and 115. 2. Five percent (1/20) of all scores are above 125, and one percent (1/100) are above 135. Similarly, five percent are below 75 and one percent below 65."

- ^ Haier, Richard (28 December 2016). The Neuroscience of Intelligence. Cambridge University Press. pp. 18–19. ISBN 9781107461437。

- ^ Cusick, Sarah E.; Georgieff, Michael K. (1 August 2017). "The Role of Nutrition in Brain Development: The Golden Opportunity of the 'First 1000 Days'". The Journal of Pediatrics. 175: 16–21. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.05.013. PMC 4981537. PMID 27266965。

- ^ Saloojee, Haroon; Pettifor, John M (15 December 2001). "Iron deficiency and impaired child development". British Medical Journal. 323 (7326): 1377–1378. doi:10.1136/bmj.323.7326.1377. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 1121846. PMID 11744547。

- ^ Qian, Ming; Wang, Dong; Watkins, William E.; Gebski, Val; Yan, Yu Qin; Li, Mu; Chen, Zu Pei (2005). "The effects of iodine on intelligence in children: a meta-analysis of studies conducted in China". Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 14 (1): 32–42. ISSN 0964-7058. PMID 15734706。

- ^ Poh, Bee Koon; Lee, Shoo Thien; Yeo, Giin Shang; Tang, Kean Choon; Noor Afifah, Ab Rahim; Siti Hanisa, Awal; Parikh, Panam; Wong, Jyh Eiin; Ng, Alvin Lai Oon; SEANUTS Study Group (13 June 2019). "Low socioeconomic status and severe obesity are linked to poor cognitive performance in Malaysian children". BMC Public Health. 19 (Suppl 4): 541. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-6856-4. ISSN 1471-2458. PMC 6565598. PMID 31196019。

- ^ Galván, Marcos; Uauy, Ricardo; Corvalán, Camila; López-Rodríguez, Guadalupe; Kain, Juliana (September 2013). "Determinants of cognitive development of low SES children in Chile: a post-transitional country with rising childhood obesity rates". Maternal and Child Health Journal. 17 (7): 1243–1251. doi:10.1007/s10995-012-1121-9. ISSN 1573-6628. PMID 22915146. S2CID 19767926。

- ^ Markus Jokela; G. David Batty; Ian J. Deary; Catharine R. Gale; Mika Kivimäki (2009). "Low Childhood IQ and Early Adult Mortality: The Role of Explanatory Factors in the 1958 British Birth Cohort". Pediatrics. 124 (3): e380–e388. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-0334. PMID 19706576. S2CID 25256969。

- ^ a b Deary & Batty 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Neisser et al. 1995.

- ^ Ronfani, Luca; Vecchi Brumatti, Liza; Mariuz, Marika; Tognin, Veronica (2015). "The Complex Interaction between Home Environment, Socioeconomic Status, Maternal IQ and Early Child Neurocognitive Development: A Multivariate Analysis of Data Collected in a Newborn Cohort Study". PLOS ONE. 10 (5): e0127052. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1027052R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0127052. PMC 4440732. PMID 25996934。

- ^ Johnson, Wendy; Turkheimer, Eric; Gottesman, Irving I.; Bouchard, Thomas J. (August 2009). "Beyond Heritability". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 18 (4): 217–220. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01639.x. PMC 2899491. PMID 20625474。

- ^ Turkheimer 2008.

- ^ Devlin, B.; Daniels, Michael; Roeder, Kathryn (1997). "The heritability of IQ". Nature. 388 (6641): 468–71. Bibcode:1997Natur.388..468D. doi:10.1038/41319. PMID 9242404. S2CID 4313884。

- ^ a b c d Schmidt, Frank L.; Hunter, John E. (1998). "The validity and utility of selection methods in personnel psychology: Practical and theoretical implications of 85 years of research findings" (PDF). Psychological Bulletin. 124 (2): 262–74. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.172.1733. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.124.2.262. S2CID 16429503. 2014年6月2日時点のオリジナル (PDF)よりアーカイブ。2017年10月25日閲覧。

- ^ Strenze, Tarmo (2007-09). “Intelligence and socioeconomic success: A meta-analytic review of longitudinal research”. Intelligence 35 (5): 401–426. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2006.09.004. ISSN 0160-2896.

- ^ Terman 1916, p. 79 "What do the above IQ's imply in such terms as feeble-mindedness, border-line intelligence, dullness, normality, superior intelligence, genius, etc.? When we use these terms two facts must be born in mind: (1) That the boundary lines between such groups are absolutely arbitrary, a matter of definition only; and (2) that the individuals comprising one of the groups do not make up a homogeneous type."

- ^ Wechsler 1939, p. 37 "The earliest classifications of intelligence were very rough ones. To a large extent they were practical attempts to define various patterns of behavior in medical-legal terms."

- ^ Bulmer, M (1999). "The development of Francis Galton's ideas on the mechanism of heredity". Journal of the History of Biology. 32 (3): 263–292. doi:10.1023/a:1004608217247. PMID 11624207. S2CID 10451997。

- ^ Cowan, R. S. (1972). "Francis Galton's contribution to genetics". Journal of the History of Biology. 5 (2): 389–412. doi:10.1007/bf00346665. PMID 11610126. S2CID 30206332。

- ^ Burbridge, D (2001). "Francis Galton on twins, heredity and social class". British Journal for the History of Science. 34 (3): 323–340. doi:10.1017/s0007087401004332. PMID 11700679。

- ^ Fancher, R. E. (1983). "Biographical origins of Francis Galton's psychology". Isis. 74 (2): 227–233. doi:10.1086/353245. PMID 6347965. S2CID 40565053。

- ^ Kaufman 2009, p. 21 "Galton's so-called intelligence test was misnamed."

- ^ Gillham, Nicholas W. (2001). "Sir Francis Galton and the birth of eugenics". Annual Review of Genetics. 35 (1): 83–101. doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.35.102401.090055. PMID 11700278。

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Kaufman 2009

- ^ Nicolas, S.; Andrieu, B.; Croizet, J.-C.; Sanitioso, R. B.; Burman, J. T. (2013). "Sick? Or slow? On the origins of intelligence as a psychological object". Intelligence. 41 (5): 699–711. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2013.08.006。 (これはオープンアクセスの記事であり、エルゼビアによって自由に利用できるようになっている)

- ^ Terman et al. 1915.

- ^ Wallin, J. E. W. (1911). "The new clinical psychology and the psycho-clinicist". Journal of Educational Psychology. 2 (3): 121–32. doi:10.1037/h0075544。

- ^ Richardson, John T. E. (2003). "Howard Andrew Knox and the origins of performance testing on Ellis Island, 1912-1916". History of Psychology. 6 (2): 143–70. doi:10.1037/1093-4510.6.2.143. PMID 12822554。

- ^ Deary 2001, pp. 6–12.

- ^ a b c d e Gould 1996

- ^ Kennedy, Carrie H.; McNeil, Jeffrey A. (2006). "A history of military psychology". In Kennedy, Carrie H.; Zillmer, Eric (eds.). Military Psychology: Clinical and Operational Applications. New York: Guilford Press. pp. 1–17. ISBN 978-1-57230-724-7。

- ^ Katzell, Raymond A.; Austin, James T. (1992). "From then to now: The development of industrial-organizational psychology in the United States". Journal of Applied Psychology. 77 (6): 803–35. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.77.6.803。

- ^ Kevles, D. J. (1968). "Testing the Army's Intelligence: Psychologists and the Military in World War I". The Journal of American History. 55 (3): 565–81. doi:10.2307/1891014. JSTOR 1891014。

- ^ Spektorowski, Alberto; Ireni-Saban, Liza (2013). Politics of Eugenics: Productionism, Population, and National Welfare. London: Routledge. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-203-74023-1. 2017年1月16日閲覧。

As an applied science, thus, the practice of eugenics referred to everything from prenatal care for mothers to forced sterilization and euthanasia. Galton divided the practice of eugenics into two types—positive and negative—both aimed at improving the human race through selective breeding.

- ^ "Eugenics". Unified Medical Language System (Psychological Index Terms). National Library of Medicine. 26 September 2010. 2024年3月14日閲覧。

- ^ Galton, Francis (July 1904). "Eugenics: Its Definition, Scope, and Aims". The American Journal of Sociology. X (1): 82, 1st paragraph. Bibcode:1904Natur..70...82.. doi:10.1038/070082a0. 2007年11月3日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2010年12月27日閲覧。

Eugenics is the science which deals with all influences that improve the inborn qualities of a race; also with those that develop them to the utmost advantage.

- ^ Susan Currell; Christina Cogdell [in 英語] (2006). Popular Eugenics: National Efficiency and American Mass Culture in the 1930s. Ohio University Press. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-0-8214-1691-4。

- ^ "Eugenics and Economics in the Progressive Era" (PDF) (英語). 2024年3月14日閲覧。

- ^ "Origins of Eugenics: From Sir Francis Galton to Virginia's Racial Integrity Act of 1924". University of Virginia: Historical Collections at the Claude Moore Health Sciences Library. 2019年10月25日閲覧。

- ^ Norrgard, K. (2008). "Human testing, the eugenics movement, and IRBs". Nature Education. 1: 170.

- ^ Galton, Francis (1869). "Hereditary Genius" (PDF). p. 64. 2019年10月1日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d "The birth of American intelligence testing". 2017年11月11日閲覧。

- ^ "America's Hidden History: The Eugenics Movement | Learn Science at Scitable". www.nature.com (英語). 2017年11月11日閲覧。

- ^ "Social Origins of Eugenics". www.eugenicsarchive.org. 2017年11月11日閲覧。

- ^ a b "The Horrifying American Roots of Nazi Eugenics". hnn.us. September 2003. 2017年11月11日閲覧。

- ^ Vizcarrondo, Felipe E. (August 2014). "Human Enhancement: The New Eugenics". The Linacre Quarterly. 81 (3): 239–243. doi:10.1179/2050854914Y.0000000021. PMC 4135459. PMID 25249705。

- ^ Regalado, Antonio. "Eugenics 2.0: We're at the Dawn of Choosing Embryos by Health, Height, and More". Technology Review. 2019年11月20日閲覧。

- ^ LeMieux, Julianna (1 April 2019). "Polygenic Risk Scores and Genomic Prediction: Q&A with Stephen Hsu". Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology News. 2019年11月20日閲覧。

- ^ Lubinski, David (2004). "Introduction to the Special Section on Cognitive Abilities: 100 Years After Spearman's (1904) "'General Intelligence,' Objectively Determined and Measured"". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 86 (1): 96–111. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.86.1.96. PMID 14717630. S2CID 6024297。

- ^ Carroll 1993, p. [要ページ番号].

- ^ Mindes, Gayle (2003). Assessing Young Children. Merrill/Prentice Hall. p. 158. ISBN 9780130929082。

- ^ Haywood, H. Carl; Lidz, Carol S. (2006). Dynamic Assessment in Practice: Clinical and Educational Applications. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 9781139462075。

- ^ Vygotsky, L.S. (1934). "The Problem of Age". The Collected Works of L. S. Vygotsky, Volume 5 (published 1998). pp. 187–205.

- ^ Chaiklin, S. (2003). "The Zone of Proximal Development in Vygotsky's analysis of learning and instruction". In Kozulin, A.; Gindis, B.; Ageyev, V.; Miller, S. (eds.). Vygotsky's educational theory and practice in cultural context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 39–64.

- ^ Zaretskii, V.K. (November–December 2009). "The Zone of Proximal Development What Vygotsky Did Not Have Time to Write". Journal of Russian and East European Psychology. 47 (6): 70–93. doi:10.2753/RPO1061-0405470604. S2CID 146894219。

- ^ Sternberg, R.S.; Grigorenko, E.L. (2001). "All testing is dynamic testing". Issues in Education. 7 (2): 137–170.

- ^ Sternberg, R.J. & Grigorenko, E.L. (2002). Dynamic testing: The nature and measurement of learning potential. Cambridge: University of Cambridge

- ^ Haywood & Lidz 2006, p. [要ページ番号].

- ^ Dodge, Kenneth A. (2006). Foreword. Dynamic Assessment in Practice: Clinical And Educational Applications. By Haywood, H. Carl; Lidz, Carol S. Cambridge University Press. pp. xiii–xv.

- ^ Kozulin, A. (2014). "Dynamic assessment in search of its identity". In Yasnitsky, A.; van der Veer, R.; Ferrari, M. (eds.). The Cambridge Handbook of Cultural-Historical Psychology. Cambridge University Press. pp. 126–147.

- ^ Das, J.P.; Kirby, J.; Jarman, R.F. (1975). "Simultaneous and successive synthesis: An alternative model for cognitive abilities". Psychological Bulletin. 82: 87–103. doi:10.1037/h0076163。

- ^ Das, J.P. (2000). "A better look at intelligence". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 11: 28–33. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.00162. S2CID 146129242。

- ^ Naglieri, J.A.; Das, J.P. (2002). "Planning, attention, simultaneous, and successive cognitive processes as a model for assessment". School Psychology Review. 19 (4): 423–442. doi:10.1080/02796015.1990.12087349。

- ^ Urbina 2011, Table 2.1 Major Examples of Current Intelligence Tests

- ^ Flanagan & Harrison 2012, chapters 8–13, 15–16 (discussing Wechsler, Stanford–Binet, Kaufman, Woodcock–Johnson, DAS, CAS, and RIAS tests)

- ^ Stanek, Kevin C.; Ones, Deniz S. (2018), “Taxonomies and Compendia of Cognitive Ability and Personality Constructs and Measures Relevant to Industrial, Work and Organizational Psychology”, The SAGE Handbook of Industrial, Work and Organizational Psychology: Personnel Psychology and Employee Performance (1 Oliver's Yard, 55 City Road London EC1Y 1SP: SAGE Publications Ltd): pp. 366–407, doi:10.4135/9781473914940.n14, ISBN 978-1-4462-0721-5 2024年1月8日閲覧。

- ^ "Primary Mental Abilities Test | psychological test". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2015年11月26日閲覧。

- ^ "Defining and Measuring Psychological Attributes". homepages.rpi.edu. 2018年10月15日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2015年11月26日閲覧。

- ^ Bain, Sherry K.; Jaspers, Kathryn E. (1 April 2010). "Test Review: Review of Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test, Second Edition Kaufman, A. S., & Kaufman, N. L. (2004). Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test, Second Edition. Bloomington, MN: Pearson, Inc". Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment. 28 (2): 167–174. doi:10.1177/0734282909348217. ISSN 0734-2829. S2CID 143961429。

- ^ Mussen, Paul Henry (1973). Psychology: An Introduction. Lexington, MA: Heath. p. 363. ISBN 978-0-669-61382-7.

The I.Q. is essentially a rank; there are no true "units" of intellectual ability.

- ^ Truch, Steve (1993). The WISC-III Companion: A Guide to Interpretation and Educational Intervention. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-89079-585-9.

An IQ score is not an equal-interval score, as is evident in Table A.4 in the WISC-III manual.

- ^ Bartholomew, David J. (2004). Measuring Intelligence: Facts and Fallacies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-521-54478-8.

When we come to quantities like IQ or g, as we are presently able to measure them, we shall see later that we have an even lower level of measurement—an ordinal level. This means that the numbers we assign to individuals can only be used to rank them—the number tells us where the individual comes in the rank order and nothing else.

- ^ Mackintosh 1998, pp. 30–31 "In the jargon of psychological measurement theory, IQ is an ordinal scale, where we are simply rank-ordering people. ... It is not even appropriate to claim that the 10-point difference between IQ scores of 110 and 100 is the same as the 10-point difference between IQs of 160 and 150"

- ^ Stevens, S. S. (1946). "On the Theory of Scales of Measurement". Science. 103 (2684): 677–680. Bibcode:1946Sci...103..677S. doi:10.1126/science.103.2684.677. PMID 17750512. S2CID 4667599。

- ^ Kaufman 2009, Figure 5.1 IQs earned by preadolescents (ages 12–13) who were given three different IQ tests in the early 2000s

- ^ Kaufman 2013, Figure 3.1 "Source: Kaufman (2009). Adapted with permission."

- ^ Mackintosh 2011, p. 169 "8~10歳以降は、IQスコアは比較的安定している。8歳から18歳までのIQスコアと40歳時のIQの相関は0.70を超える"

- ^ a b c d e f Weiten W (2016). Psychology: Themes and Variations. Cengage Learning. p. 281. ISBN 978-1305856127。

- ^ "WISC-V Interpretive Report Sample" (PDF). Pearson. p. 18. 2020年9月29日閲覧。

- ^ Kaufman, Alan S.; Raiford, Susan Engi; Coalson, Diane L. (2016). Intelligent testing with the WISC-V. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. pp. 683–702. ISBN 978-1-118-58923-6.

表4.1の信頼性推定値と表4.4の測定の標準誤差は、一時的な誤差、実施上の誤差、採点上の誤差(Hanna, Bradley, & Holen, 1981)など、臨床評価でテストスコアに影響を与える他の主要な誤差源を考慮していないため、最良の推定値と見なすべきである。考慮すべきもう1つの要因は、下位検査のスコアが、階層的な一般知能因子によって真のスコア分散の一部を反映している程度と、特定の集団因子によって分散を反映している程度である。これらの真のスコア分散の源は混同されているためである。

- ^ Whitaker, Simon (April 2010). "Error in the estimation of intellectual ability in the low range using the WISC-IV and WAIS-III". Personality and Individual Differences. 48 (5): 517–521. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2009.11.017. 2020年1月22日閲覧。

- ^ Lohman & Foley Nicpon 2012, p. [要ページ番号]. "SEMs[測定の標準誤差]に関連する懸念は、実際には分布の両端、特にスコアが検査で可能な最大値に近づく場合に、かなり悪化する...生徒がほとんどの項目に正しく答える場合。このような場合、尺度スコアの測定誤差は分布の両端で大幅に増加する。一般的に、SEMは平均付近のスコアよりも非常に高いスコアの方が2~4倍大きい(Lord, 1980)"

- ^ Urbina 2011, p. 20 "[曲線あてはめ]は、160をはるかに超えるIQスコアの報告を疑う理由の1つに過ぎない"

- ^ Gould 1981, p. 24. Gould 1996, p. 56.

- ^ Kaplan, Jonathan Michael; Pigliucci, Massimo; Banta, Joshua Alexander (2015). "Gould on Morton, Redux: What can the debate reveal about the limits of data?" (PDF). Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences. 30: 1–10.

- ^ Weisberg, Michael; Paul, Diane B. (19 April 2016). "Morton, Gould, and Bias: A Comment on "The Mismeasure of Science"". PLOS Biology. 14 (4). e1002444. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1002444. ISSN 1544-9173. PMC 4836680. PMID 27092558。

- ^ "25 Greatest Science Books of All Time". Discover. 7 December 2006.

- ^ ブルックス、デビッド(2007年9月14日)。"The Waning of I.Q."。ニューヨーク・タイムズ.

- ^ Sternberg, Robert J., and Richard K. Wagner. "The g-ocentric view of intelligence and job performance is wrong." Current directions in psychological science (1993): 1–5.

- ^ Anastasi & Urbina 1997, pp. 326–327.

- ^ Embretson, S. E., Reise, S. P. (2000).Item Response Theory for Psychologists. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- ^ a b c d Zumbo, B.D. (2007). "Three generations of differential item functioning (DIF) analyses: Considering where it has been, where it is now, and where it is going". Language Assessment Quarterly. 4 (2): 223–233. doi:10.1080/15434300701375832. S2CID 17426415。

- ^ Verney, SP; Granholm, E; Marshall, SP; Malcarne, VL; Saccuzzo, DP (2005). "Culture-Fair Cognitive Ability Assessment: Information Processing and Psychophysiological Approaches". Assessment. 12 (3): 303–19. doi:10.1177/1073191105276674. PMID 16123251. S2CID 31024437。

- ^ Shuttleworth-Edwards, Ann; Kemp, Ryan; Rust, Annegret; Muirhead, Joanne; Hartman, Nigel; Radloff, Sarah (2004). "Cross-cultural Effects on IQ Test Performance: AReview and Preliminary Normative Indications on WAIS-III Test Performance". Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 26 (7): 903–20. doi:10.1080/13803390490510824. PMID 15742541. S2CID 16060622。

- ^ Cronshaw, Steven F.; Hamilton, Leah K.; Onyura, Betty R.; Winston, Andrew S. (2006). "Case for Non-Biased Intelligence Testing Against Black Africans Has Not Been Made: A Comment on Rushton, Skuy, and Bons (2004)". International Journal of Selection and Assessment. 14 (3): 278–87. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2389.2006.00346.x. S2CID 91179275。

- ^ Edelson, M. G. (2006). "Are the Majority of Children With Autism Mentally Retarded?: A Systematic Evaluation of the Data". Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 21 (2): 66–83. doi:10.1177/10883576060210020301. S2CID 145809356。

- ^ Ulric Neisser; James R. Flynn; Carmi Schooler; Patricia M. Greenfield; Wendy M. Williams; Marian Sigman; Shannon E. Whaley; Reynaldo Martorell; et al. (1998). Neisser, Ulric (ed.). The Rising Curve: Long-Term Gains in IQ and Related Measures. APA Science Volume Series. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. ISBN 978-1-55798-503-3。[要ページ番号]

- ^ Mackintosh 1998, p. [要ページ番号].

- ^ a b Flynn 2009, p. [要ページ番号].

- ^ Flynn, James R. (1984). "The mean IQ of Americans: Massive gains 1932 to 1978". Psychological Bulletin. 95 (1): 29–51. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.95.1.29. S2CID 51999517。

- ^ Flynn, James R. (1987). "Massive IQ gains in 14 nations: What IQ tests really measure". Psychological Bulletin. 101 (2): 171–91. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.101.2.171。

- ^ Zhou, Xiaobin; Grégoire, Jacques; Zhu, Jianjin (2010). "The Flynn Effect and the Wechsler Scales". In Weiss, Lawrence G.; Saklofske, Donald H.; Coalson, Diane; Raiford, Susan (eds.). WAIS-IV Clinical Use and Interpretation: Scientist-Practitioner Perspectives. Practical Resources for the Mental Health Professional. Amsterdam: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-375035-8。[要ページ番号]

- ^ Mackintosh 2011, pp. 25–27.

- ^ Schacter, Daniel L.; Gilbert, Daniel T.; Wegner, Daniel M. (2011). Psychology. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 384. ISBN 978-0230579835。

- ^ a b c d Bratsberg, Bernt; Rogeberg, Ole (26 June 2018). "Flynn effect and its reversal are both environmentally caused". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 115 (26): 6674–6678. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115.6674B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1718793115. PMC 6042097. PMID 29891660。

- ^ Kaufman 2009, pp. 220–222.

- ^ Kaufman 2009, p. [要ページ番号], "Chapter 8".

- ^ Desjardins, Richard; Warnke, Arne Jonas (2012). "Ageing and Skills". OECD Education Working Papers. doi:10.1787/5k9csvw87ckh-en. hdl:10419/57089。

- ^ 辰野1995

- ^ a b Underwood, E. (2014-10-31). “Starting young” (英語). Science 346 (6209): 568–571. doi:10.1126/science.346.6209.568. ISSN 0036-8075.

- ^ D.K.Detterman (2003年8月3日). “MSN Learning & Research - Intelligence”. web.archive.org. 2019年8月30日閲覧。

- ^ 原典に版の表記はないが、出版の時期から見て第4版と思われる。

- ^ a b c 日本版WISC-III刊行委員会

- ^ 田中教育研究所2003

- ^ Tucker-Drob, Elliot M; Briley, Daniel A (2014), “Continuity of Genetic and Environmental Influences on Cognition across the Life Span: A Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Twin and Adoption Studies”, Psychological Bulletin 140 (4): 949–979, doi:10.1037/a0035893, PMC 4069230, PMID 24611582

- ^ Bouchard, Thomas J. (7 August 2013). "The Wilson Effect: The Increase in Heritability of IQ With Age". Twin Research and Human Genetics. 16 (5): 923–930. doi:10.1017/thg.2013.54. PMID 23919982. S2CID 13747480。

- ^ Panizzon, Matthew S.; Vuoksimaa, Eero; Spoon, Kelly M.; Jacobson, Kristen C.; Lyons, Michael J.; Franz, Carol E.; Xian, Hong; Vasilopoulos, Terrie; Kremen, William S. (March 2014). "Genetic and environmental influences on general cognitive ability: Is g a valid latent construct?". Intelligence. 43: 65–76. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2014.01.008. PMC 4002017. PMID 24791031。

- ^ Huguet, Guillaume; Schramm, Catherine; Douard, Elise; Jiang, Lai; Labbe, Aurélie; Tihy, Frédérique; Mathonnet, Géraldine; Nizard, Sonia; et al. (May 2018). "Measuring and Estimating the Effect Sizes of Copy Number Variants on General Intelligence in Community-Based Samples". JAMA Psychiatry. 75 (5): 447–457. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.0039. PMC 5875373. PMID 29562078。

- ^ Bouchard, TJ Jr. (1998). "Genetic and environmental influences on adult intelligence and special mental abilities". Human Biology; an International Record of Research. 70 (2): 257–79. PMID 9549239。

- ^ a b Plomin, R; Asbury, K; Dunn, J (2001). "Why are children in the same family so different? Nonshared environment a decade later". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 46 (3): 225–33. doi:10.1177/070674370104600302. PMID 11320676。

- ^ Harris 2009, p. [要ページ番号].

- ^ Pietropaolo, S.; Crusio, W. E. (2010). "Genes and cognition". Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science. 2 (3): 345–352. doi:10.1002/wcs.135. PMID 26302082。

- ^ Deary, Johnson & Houlihan 2009.

- ^ Davies G, Tenesa A, Payton A, Yang J, Harris SE, Liewald D, Ke X, Le Hellard S, et al. (2011). "Genome-wide association studies establish that human intelligence is highly heritable and polygenic". Mol Psychiatry. 16 (10): 996–1005. doi:10.1038/mp.2011.85. PMC 3182557. PMID 21826061。

- ^ Benyamin B, Pourcain B, Davis OS, Davies G, Hansell NK, Brion MJ, Kirkpatrick RM, Cents RA, et al. (2013). "Childhood intelligence is heritable, highly polygenic and associated with FNBP1L". Mol Psychiatry. 19 (2): 253–258. doi:10.1038/mp.2012.184. PMC 3935975. PMID 23358156。

- ^ Sniekers S, Stringer S, Watanabe K, Jansen PR, Coleman JRI, Krapohl E, Taskesen E, Hammerschlag AR, Okbay A, Zabaneh D, Amin N, Breen G, Cesarini D, Chabris CF, Iacono WG, Ikram MA, Johannesson M, Koellinger P, Lee JJ, Magnusson PKE, McGue M, Miller MB, Ollier WER, Payton A, Pendleton N, Plomin R, Rietveld CA, Tiemeier H, van Duijn CM, Posthuma D. Genome-wide association meta-analysis of 78,308 individuals identifies new loci and genes influencing human intelligence. Nat Genet. 2017 Jul;49(7):1107-1112. doi: 10.1038/ng.3869. Epub 2017 May 22. Erratum in: Nat Genet. 2017 Sep 27;49(10 ):1558. PMID 28530673; PMCID: PMC5665562.

- ^ Benyamin B, Pourcain B, Davis OS, Davies G, Hansell NK, Brion MJ, Kirkpatrick RM, Cents RA, Franić S, Miller MB, Haworth CM, Meaburn E, Price TS, Evans DM, Timpson N, Kemp J, Ring S, McArdle W, Medland SE, Yang J, Harris SE, Liewald DC, Scheet P, Xiao X, Hudziak JJ, de Geus EJ; Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 2 (WTCCC2); Jaddoe VW, Starr JM, Verhulst FC, Pennell C, Tiemeier H, Iacono WG, Palmer LJ, Montgomery GW, Martin NG, Boomsma DI, Posthuma D, McGue M, Wright MJ, Davey Smith G, Deary IJ, Plomin R, Visscher PM. Childhood intelligence is heritable, highly polygenic and associated with FNBP1L. Mol Psychiatry. 2014 Feb;19(2):253-8. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.184. Epub 2013 Jan 29. PMID 23358156; PMCID: PMC3935975.

- ^ Rowe, D. C.; Jacobson, K. C. (1999). "Genetic and environmental influences on vocabulary IQ: parental education level as moderator". Child Development. 70 (5): 1151–62. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00084. PMID 10546338. S2CID 10959764。

- ^ Tucker-Drob, E. M.; Rhemtulla, M.; Harden, K. P.; Turkheimer, E.; Fask, D. (2011). "Emergence of a Gene x Socioeconomic Status Interaction on Infant Mental Ability Between 10 Months and 2 Years". Psychological Science. 22 (1): 125–33. doi:10.1177/0956797610392926. PMC 3532898. PMID 21169524。

- ^ Turkheimer, E.; Haley, A.; Waldron, M.; D'Onofrio, B.; Gottesman, I. I. (2003). "Socioeconomic status modifies heritability of IQ in young children". Psychological Science. 14 (6): 623–628. doi:10.1046/j.0956-7976.2003.psci_1475.x. PMID 14629696. S2CID 11265284。

- ^ Harden, K. P.; Turkheimer, E.; Loehlin, J. C. (2005). "Genotype environment interaction in adolescents' cognitive ability". Behavior Genetics. 35 (6): 804. doi:10.1007/s10519-005-7287-9. S2CID 189842802。

- ^ Bates, Timothy C.; Lewis, Gary J.; Weiss, Alexander (3 September 2013). "Childhood Socioeconomic Status Amplifies Genetic Effects on Adult Intelligence" (PDF). Psychological Science. 24 (10): 2111–2116. doi:10.1177/0956797613488394. hdl:20.500.11820/52797d10-f0d4-49de-83e2-a9cc3493703d. PMID 24002887. S2CID 1873699。

- ^ a b c d Tucker-Drob, Elliot M.; Bates, Timothy C. (15 December 2015). "Large Cross-National Differences in Gene × Socioeconomic Status Interaction on Intelligence". Psychological Science. 27 (2): 138–149. doi:10.1177/0956797615612727. PMC 4749462. PMID 26671911。

- ^ Hanscombe, K. B.; Trzaskowski, M.; Haworth, C. M.; Davis, O. S.; Dale, P. S.; Plomin, R. (2012). "Socioeconomic Status (SES) and Children's Intelligence (IQ): In a UK-Representative Sample SES Moderates the Environmental, Not Genetic, Effect on IQ". PLOS ONE. 7 (2): e30320. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...730320H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0030320. PMC 3270016. PMID 22312423。

- ^ Dickens, William T.; Flynn, James R. (2001). "Heritability estimates versus large environmental effects: The IQ paradox resolved" (PDF). Psychological Review. 108 (2): 346–69. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.139.2436. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.108.2.346. PMID 11381833。