「オキアミ」の版間の差分

タグ: モバイル編集 モバイルウェブ編集 |

|||

| (他の1人の利用者による、間の1版が非表示) | |||

| 1行目: | 1行目: | ||

{{出典の明記|date=2016年6月17日 (金) 11:35 (UTC)}} |

|||

{{生物分類表 |

{{生物分類表 |

||

|名称 = オキアミ目 |

|名称 = オキアミ目 |

||

|色 = 動物界 |

|色 = 動物界 |

||

|画像 =[[ファイル:Meganyctiphanes norvegica2.jpg|250px]] |

|画像 = [[ファイル:Meganyctiphanes norvegica2.jpg|250px]] |

||

|画像キャプション = ''Meganyctiphanes norvegica'' |

|画像キャプション = [[w:Northern krill|Northern krill]] ''Meganyctiphanes norvegica'' |

||

|界 = [[動物界]] [[w:Animalia|Animalia]] |

|界 = [[動物界]] [[w:Animalia|Animalia]] |

||

|門 = [[節足動物門]] [[w:Arthropoda|Arthropoda]] |

|門 = [[節足動物門]] [[w:Arthropoda|Arthropoda]] |

||

| 11行目: | 10行目: | ||

|亜綱 = [[真軟甲亜綱]] [[w:Eumalacostraca|Eumalacostraca]] |

|亜綱 = [[真軟甲亜綱]] [[w:Eumalacostraca|Eumalacostraca]] |

||

|上目 = [[ホンエビ上目]] [[:w:Eucarida|Eucarida]] |

|上目 = [[ホンエビ上目]] [[:w:Eucarida|Eucarida]] |

||

|目 = '''オキアミ目''' [[:w:Euphausiacea|Euphausiacea]]<br/ |

|目 = '''オキアミ目''' [[:w:Euphausiacea|Euphausiacea]] |

||

|学名 = [[:w:Euphausiacea|Euphausiacea]]<br/>[[ジェームズ・デーナ|Dana]], [[1852年|1852]] |

|||

|英名 = [[w:Krill|Krill]] |

|||

|下位分類名 = [[科 (分類学)|科]] |

|下位分類名 = [[科 (分類学)|科]] |

||

|下位分類 = |

|下位分類 = |

||

* [[オキアミ科]] [[:w:Euphausiidae|Euphausiidae]] |

* [[オキアミ科]] [[:w:Euphausiidae|Euphausiidae]] |

||

* [[ソコオキアミ科]] [[:w:Bentheuphausiidae|Bentheuphausiidae]] |

* [[ソコオキアミ科]] [[:w:Bentheuphausiidae|Bentheuphausiidae]] |

||

|和名 = オキアミ |

|||

|英名 = Krill |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

'''オキアミ'''(沖醤蝦、{{lang-en-short|krill}})は、[[軟甲綱]] [[真軟甲亜綱]] [[ホンエビ上目]] |

'''オキアミ'''(沖醤蝦、{{lang-en-short|krill}})は、[[軟甲綱]] [[真軟甲亜綱]] [[ホンエビ上目]] '''オキアミ目'''に属する[[甲殻類]]の総称。学名から Euphausiids とも呼ばれる<ref name="Euphausiids (Krill)">{{cite web |title=Euphausiids (Krill) |url=https://parks.canada.ca/amnc-nmca/qc/saguenay/info/plan/gestion-management#section8-0 |website=Government of Canada |publisher=Fisheries and Oceans Canada |access-date=2024-12-07 |date=2022-04-06 |quote=Many different species of euphausiids are found on Canada's east and west coasts.}}</ref>。英名の「Krill」は[[ノルウェー語]]で「[[稚魚]]」を意味する<ref>{{cite encyclopedia|url=http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?search=krill|title=Krill|dictionary=Online Etymology Dictionary|access-date=2024-12-07}}</ref>。世界中の海洋に生息する小型甲殻類である<ref>{{Cite book |title=Crustacea: Euphausiacea |url=https://academic.oup.com/book/25513/chapter/192772141 |publisher=Oxford University Press |date=2017-10-19 |volume=1 |doi=10.1093/oso/9780199233267.003.0030 |language=en |first=Alistair J. |last=Lindley}}</ref>。形態は[[エビ]]に似るが、胸肢の付け根に[[鰓]]が露出している点で[[エビ目]]とは区別できる<ref>大塚攻・駒井智幸 「3.甲殻亜門」 『節足動物の多様性と系統』 [[石川良輔]]編、岩槻邦男・馬渡峻輔監修、裳華房、2008年、172-268頁</ref>。[[プランクトン|プランクトン(浮遊生物)]]であるが、体長3-6cmなのでプランクトンとしてはかなり大きい。 |

||

[[食物連鎖]]の底辺に近く、重要な栄養段階を占めると考えられている。[[植物プランクトン]]や[[動物プランクトン]]を食べ、多くの大型動物の主な食料源でもある。[[南極海]]における[[ナンキョクオキアミ]]の推定バイオマス量は約3億7900万トンで<ref>{{cite journal|author1=A. Atkinson |author2=V. Siegel |author3=E.A. Pakhomov |author4=M.J. Jessopp |author5=V. Loeb |title=A re-appraisal of the total biomass and annual production of Antarctic krill |journal=Deep-Sea Research Part I |year=2009 |volume=56 |issue=5 |pages=727–740 |url=http://www.iced.ac.uk/documents/Atkinson%20et%20al,%20Deep%20Sea%20Research%20I,%202009.pdf |doi=10.1016/j.dsr.2008.12.007|bibcode=2009DSRI...56..727A }}</ref>、総バイオマス量が最も大きい種の1つとなっている。ナンキョクオキアミの半分以上は、毎年[[クジラ]]、[[アザラシ]]、[[ペンギン]]、[[海鳥]]、[[イカ]]、[[魚類]]に食べられている。ほとんどのオキアミは毎日大規模な{{仮リンク|日周鉛直移動|en|Diel vertical migration}}を行い、夜間は海面近くで、日中は[[深海]]で生活する。 |

|||

漁獲されたオキアミは漁業用の飼料や釣り餌などとして市販されており、日本で販売されているのは、三陸沖などで漁獲される[[ツノナシオキアミ]](イサダ)と、南極海に生息する[[ナンキョクオキアミ]]である。 後者は[[ヒゲクジラ]]類の主要な餌料である。 |

|||

南極海と日本近海では商業的に漁獲されている。世界全体の漁獲量は年間15万-20万トンで、そのほとんどは[[スコシア海]]で漁獲される。漁獲されたオキアミのほとんどは[[養殖]]や[[水族館]]の餌、[[スポーツフィッシング]]の餌、または[[製薬]]において使われる。日本で販売されているのは、三陸沖などで漁獲される[[ツノナシオキアミ]](イサダ)と、南極海に生息する[[ナンキョクオキアミ]]である。 後者は[[シロナガスクジラ]]など[[ヒゲクジラ]]類の主要な餌料である。オキアミはいくつかの国で食用にもされている。[[スペイン]]と[[フィリピン]]では ''camarones'' として知られている。フィリピンでは ''alamang'' とも呼ばれ、[[バゴーン]]と呼ばれる塩辛いペーストを作るのに使われている。日本で「アミエビ」の名で[[塩辛]]などの食品として売られているものは本種ではなく、より小型の名称の似たエビの一種である「[[アキアミ]]」である。 |

|||

「アミエビ」の名で[[塩辛]]などの食品として売られているものは本種ではなく、もっと小型の名称の似たエビの一種である「[[アキアミ]]」である。 |

|||

== |

== 分類 == |

||

オキアミ目には2科が知られている。オキアミ科には10属に約85種が分類され、オキアミ属には最多の31種が属する<ref>{{Cite WoRMS|id=110671|title=Euphausiidae Dana, 1852|db=krill|year=2024|access-date=2024-12-07|last=Siegel|first=Volker}}</ref>。ソコオキアミ科には水深1000m以上の深海に生息するソコオキアミ1種のみが分類され、現存するオキアミの中で最も原始的な種と考えられている<ref>{{cite journal |author=E. Brinton |title=The distribution of Pacific euphausiids |journal=Bull. Scripps Inst. Oceanogr. |volume=8 |issue=2 |pages=51–270 |year=1962 |url=http://escholarship.org/uc/item/6db5n157}}</ref>。ナンキョクオキアミ、ツノナシオキアミ、Northern krillなどは商業漁業の対象となる<ref name="nicol">{{cite journal |author1=S. Nicol |author2=Y. Endo |year=1999 |title=Krill fisheries: Development, management and ecosystem implications |journal=Aquatic Living Resources |volume=12 |issue=2 |pages=105–120 |doi=10.1016/S0990-7440(99)80020-5|s2cid=84158071 |url=https://www.alr-journal.org/10.1016/S0990-7440(99)80020-5/pdf }}</ref>。 |

|||

外見的には遊泳生の[[エビ]]類によく似ており、[[頭胸部]]は背甲に覆われ、腹部は6節からなる腹節と尾節からなる。胸部には8節があり、それぞれに附属肢があるが、エビを含む[[十脚類]]ではその前3対が顎脚となっているのに対して、オキアミ類ではそのような変形が見られない。第2,第3節が鋏脚として発達する例や、最後の1-2対が退化する例もある。それらの胸部附属肢の基部の節には外に向けて発達した樹枝状の鰓がある。これが背甲に覆われないのもエビ類との違いである。 |

|||

=== 系統 === |

|||

なお、よく似たものに[[アミ目]]のものがあるが、胸脚の基部に鰓がないこと、尾肢に[[平衡胞]]がある点などで区別される。分類上はアミ目はフクロエビ上目とされ、系統的にもやや遠いと考えられている。 |

|||

{{cladogram |

|||

|title=オキアミ目の系統分類<ref name="Maas"/> |

|||

|caption=系統分類は形態学に基づき、(♠) はMaas & Waloszek(2001)内で提唱された分類群で<ref name="Maas"/>、(♣) はネマトブラキオン属と関連する[[側系統群]]であり<ref name="Maas"/>、(♦) はCasanova (1984)とは異なり<ref name="casanova">{{cite journal |author=Bernadette Casanova |year=1984 |title=Phylogénie des Euphausiacés (Crustacés Eucarides) |language=fr |trans-title=Phylogeny of the Euphausiacea (Crustacea: Eucarida) |journal=Bulletin du Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle |volume=4 |pages=1077–1089}}</ref>、カクエリオキアミ属は ''Nyctiphanes'' の[[姉妹群]]、オキアミ属はチサノポーダ属の姉妹群、ネマトブラキオン属はスティロケイロン属の姉妹群である。 |

|||

|align=right |

|||

|cladogram= |

|||

{{clade| style=font-size:75%;line-height:75% |

|||

|label1=オキアミ目 |

|||

|1={{clade |

|||

|label1=ソコオキアミ科 |

|||

|1=[[ソコオキアミ]] |

|||

|label2= オキアミ科 |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|1=[[チサノポーダ属]] (♣) |

|||

|2=[[ネマトブラキオン属]] (♦) |

|||

|label3=Euphausiinae |

|||

|3={{clade |

|||

|1={{snamei||Meganyctiphanes}} |

|||

|label2=Euphausiini (♠)(♦) |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|1=[[カクエリオキアミ属]] |

|||

|2=[[オキアミ属]] |

|||

}} |

|||

|label3=Nematoscelini (♠) |

|||

|3={{clade |

|||

|1={{snamei||Nyctiphanes}} |

|||

|label2=Nematoscelina (♠) |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|1={{snamei||Nematoscelis}} |

|||

|2=[[チサノエッサ属]] |

|||

|3=[[テッサラブラキオン属]] |

|||

|4=[[スティロケイロン属]] |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

オキアミ目は裸出した樹枝状の鰓や細い胸脚など、いくつかの独特な[[固有派生形質]]を持つため、[[単系統群]]であると考えられており<ref name="casanova03">{{cite journal |author=Bernadette Casanova |title=Ordre des Euphausiacea Dana, 1852 |journal=Crustaceana |volume=76 |issue=9 |year=2003 |pages=1083–1121 |doi=10.1163/156854003322753439 |jstor=20105650}}</ref>、分子生物学的研究によっても同様の結果が得られている<ref>{{cite journal |author1=M. Eugenia D'Amato |author2=Gordon W. Harkins |author3=Tulio de Oliveira |author4=Peter R. Teske |author5=Mark J. Gibbons |year=2008 |title=Molecular dating and biogeography of the neritic krill ''Nyctiphanes'' |url=http://www.bioafrica.net/manuscripts/AmatoMarineBiology.pdf |journal=[[w:Marine Biology (journal)|Marine Biology]] |volume=155 |issue=2 |pages=243–247 |doi=10.1007/s00227-008-1005-0 |s2cid=17750015 |access-date=2010-07-04 |archive-date=2012-03-17 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120317023748/http://www.bioafrica.net/manuscripts/AmatoMarineBiology.pdf |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref name="Jarman">{{cite journal |author=Simon N. Jarman |year=2001 |title=The evolutionary history of krill inferred from nuclear large subunit rDNA sequence analysis |journal=Biological Journal of the Linnean Society |volume=73 |issue=2 |pages=199–212 |doi=10.1111/j.1095-8312.2001.tb01357.x|doi-access=free }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author1=Xin Shen |author2=Haiqing Wang |author3=Minxiao Wang |author4=Bin Liu |year=2011 |title=The complete mitochondrial genome sequence of ''Euphausia pacifica'' (Malacostraca: Euphausiacea) reveals a novel gene order and unusual tandem repeats |journal=[[w:Genome (journal)|Genome]] |volume=54 |issue=11 |pages=911–922 |doi=10.1139/g11-053 |pmid=22017501}}</ref>。 |

|||

== 生殖と発生 == |

|||

雌雄異体で、雄は雌の第6胸脚の基部にある生殖孔に精胞をつける。[[精子]]はここに侵入して、一時的に貯精嚢に蓄えられる。[[受精卵]]は普通、そのまま海中に放出される。この点も、保育嚢を持つアミ類とは異なる。一部では胸脚の一部が広がって抱卵肢のようになることが知られる。 |

|||

オキアミ目の位置については多くの説がある。1830年に[[アンリ・ミルヌ=エドワール]]が初めて ''Thysanopode tricuspide'' を記載し、どちらも二枝に分かれた胸脚を持つため、当時の学者はオキアミ目と[[アミ目]]を裂脚目 Schizopoda に分類したが、1883年に{{仮リンク|ヨハン・エリック・ヴェスティ・ボアズ|en|Johan Erik Vesti Boas}}は裂脚目を2つの目に分割した<ref name="Boas">{{cite journal |author=Johan Erik Vesti Boas |year=1883 |title=Studien über die Verwandtschaftsbeziehungen der Malacostraken |language=de |trans-title=Studies on the relationships of the Malacostraca |journal=Morphologisches Jahrbuch |volume=8 |pages=485–579}}</ref>。1904年に{{仮リンク|ウィリアム・トーマス・カルマン|en|William Thomas Calman}}はアミ目を[[フクロエビ上目]]、オキアミ目をホンエビ上目に分類したが、1930年代までは裂脚目を認める意見もあった<ref name="casanova03"/>。その後は{{仮リンク|ロバート・ガーニー|en|Robert Gurney}}と{{仮リンク|イザベラ・ゴードン|en|Isabella Gordon}}が指摘したように、発達段階の類似性に基づき、[[十脚目]]の[[クルマエビ科]]と同じグループに分類されるべきであると提案された<ref name="Gurney">{{cite book |author=Robert Gurney |year=1942 |publisher=Ray Society |title=Larvae of Decapod Crustacea |url=http://decapoda.arthroinfo.org/pdfs/12852/12852.pdf }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Isabella Gordon |year=1955 |title=Systematic position of the Euphausiacea |journal=[[w:Nature (journal)|Nature]] |volume=176 |issue=4489 |pages=934 |doi=10.1038/176934a0 |bibcode=1955Natur.176..934G|s2cid=4225121 |doi-access=free }}</ref>。オキアミは十脚目とアミ目の形態学的特徴の一部を共有しているため、こうした議論が起こったのである<ref name="casanova03"/>。 |

|||

孵化した幼生は三対の附属肢を持つ[[ノープリウス]]で、二期のノープリウスの後にメタノープリウス期となり、ほぼ体全体が背甲に覆われる。その後、腹部が伸長したカリプトピス期から複眼が柄を持って突き出すフルキリア期を経て、その間に附属肢が発達して成体に至る。生息域によっても異なるが、成熟までに1-3年を要すると考えられている。 |

|||

分子生物学的研究では、ソコオキアミや[[アンフィオニデス]]など重要な種が少ないためか、明確な分類が出来ていない。ある研究では基底的なアミ目を含むホンエビ上目の単系統性を支持しており<ref name="Spears, T. 2005">{{cite journal |author=Trisha Spears, Ronald W. DeBry, Lawrence G. Abele & Katarzyna Chodyl |year=2005 |title=Peracarid monophyly and interordinal phylogeny inferred from nuclear small-subunit ribosomal DNA sequences (Crustacea: Malacostraca: Peracarida) |journal=Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington |volume=118 |issue=1 |pages=117–157 |doi=10.2988/0006-324X(2005)118[117:PMAIPI]2.0.CO;2 |s2cid=85557065 |url=http://decapoda.nhm.org/pdfs/10231/10231.pdf |editor1-last=Boyko |editor1-first=Christopher B.}}</ref>、別の研究ではオキアミ目をアミ目と分類し<ref name="Jarman"/>、さらに別の研究ではオキアミ目を{{仮リンク|トゲエビ亜綱|en|Hoplocarida}}と分類している<ref>{{cite journal |author1=K. Meland |author2=E. Willassen |year=2007 |title=The disunity of "Mysidacea" (Crustacea) |journal=Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution |volume=44 |pages=1083–1104 |doi=10.1016/j.ympev.2007.02.009 |pmid=17398121 |issue=3|citeseerx=10.1.1.653.5935 }}</ref>。 |

|||

== 生態 == |

|||

オキアミは全て海産で、その大部分が外洋の表層から中深層を遊泳して生活する[[プランクトン]]である。多くの場合、幼生はやや表層で生活し、成熟に連れて次第に深いところへ移動する傾向がある。また、浅海生のものは日周鉛直運動をする。プランクトン食とされ、種によって動物プランクトンか植物プランクトンのどちらを主食とするかが決まっているらしい。 |

|||

=== 進化 === |

|||

[[ナンキョクオキアミ]]は南極海において非常に大きな現存量を持ち、[[生態系]]全体に大きな影響を持つ[[キーストーン種]]である。 |

|||

オキアミ目と明確に特定できる化石は現在知られていない。絶滅した[[真軟甲亜綱]]の中には、''Anthracophausia''、現在は{{仮リンク|奇泳目|en|Aeschronectida}}に分類されている {{snamei||Crangopsis}} <ref name="Maas">{{cite journal |author1=Andreas Maas |author2=Dieter Waloszek |year=2001 |title=Larval development of ''Euphausia superba'' Dana, 1852 and a phylogenetic analysis of the Euphausiacea |url=http://biosys-serv.biologie.uni-ulm.de/Downloadfolder/PDFs%20Team/2001_Maas&Waloszek_Euphausia.pdf |journal=Hydrobiologia |volume=448 |pages=143–169 |doi=10.1023/A:1017549321961 |s2cid=32997380 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110718095311/http://biosys-serv.biologie.uni-ulm.de/Downloadfolder/PDFs%20Team/2001_Maas%26Waloszek_Euphausia.pdf |archive-date=18 July 2011 }}</ref>、''Palaeomysis'' など、オキアミ目に分類されてきた属も存在する<ref name="Schram86">{{cite book |author=Frederick R. Schram |year=1986 |title=Crustacea |isbn=978-0-19-503742-5 |publisher=Oxford University Press}}</ref>。種分化の年代は[[分子時計]]によって推定されており、オキアミ科の最後の共通祖先は、約1億3千万年前の[[前期白亜紀]]に生息していたとされる<ref name="Jarman"/>。 |

|||

== |

=== 下位分類 === |

||

主に和名のある種を挙げる。和名と種数は佐々木(2023)を参考<ref>佐々木潤 (2023) [https://www.researchgate.net/publication/376519923_The_Species_List_of_Decapoda_Euphausiacea_and_Stomatopoda_all_of_the_World_Version_07-812-Worldwide_species_list_of_Decapoda_Euphausiacea_and_Stomatopoda- 世界大型甲殻類目録 The Species List of Decapoda,Euphausiacea, and Stomatopoda,all of the World. Version. 07-8.12] 2024年12月6日閲覧。</ref>。 |

|||

漁獲されたオキアミは未加工もしくは[[フリーズドライ]]加工され、または粉末状で販売され、養殖漁業の飼料用、[[釣り餌]]、観賞魚の餌などに利用される。飼料としてのオキアミには、魚の耐病性向上や、観賞魚の体色の発色向上などの効果があって人気が高い。日本では[[ナンキョクオキアミ]]の34%、[[ツノナシオキアミ]]の50%が魚の飼料として消費される。また日本では70年代に海釣りの撒きえさとして導入され、[[黒鯛]]や[[メジナ]]、また[[サビキ釣り]]のテクニックに革命を起こした。ナンキョクオキアミの4分の1、ツノナシオキアミの半分は釣りえさ用である。 |

|||

* [[オキアミ科]] {{sname||Euphausiidae}} |

|||

オキアミは[[蛋白質]]や[[ビタミン類]]を多く含み、[[魚肉ソーセージ]]など[[加工食品]]の原料になり<ref>{{Cite web|和書|url=https://mdinfo.jccu.coop/bb/shohindetail/4902220146468/psspu:013553 |title=コープ商品検索トップ > 惣菜・デイリー > 魚肉ソーセージ > チルドおさかなソーセージ 8本入(160g) |access-date=2022-12-25 |publisher=coop}}</ref>、また調味料として塩辛も作られている。これは朝鮮半島や日本で[[キムチ]]の[[発酵]]に[[アキアミ]]の塩辛同様に使われる事がある<ref>[http://www.bingotukemono.jp/blog/489.html 吉野家白菜キムチ 200g - キムチ、大根のお漬物なら備後漬物株式会社]</ref>。以前は漁獲後の劣化が早く風味落ちがするため、人間の食用としての消費はきわめて少なかったが、近年加工技術の進化により、ツノナシオキアミは[[サクラエビ]]の安価な代用品として[[お好み焼き]]などに利用されている。 |

|||

** [[オキアミ属]] ''{{sname||Euphausia}}'' - 34種 |

|||

*** [[コオリオキアミ]] ''Euphausia crystallorophias'' |

|||

*** [[ツノナシオキアミ]] ''Euphausia pacifica'' |

|||

*** [[ナンキョクオキアミ]] ''Euphausia superba'' |

|||

** {{snamei||Hansarsia}} - 7種 |

|||

*** [[ホソテナガオキアミ]] ''Hansarsia tenella'' |

|||

** {{snamei||Meganyctiphanes}} - 1種 |

|||

** [[ネマトブラキオン属]] {{snamei||Nematobrachion}} - 3種 |

|||

** {{snamei||Nyctiphanes}} - 4種 |

|||

** [[カクエリオキアミ属]] {{snamei||Pseudeuphausia}} - 3種 |

|||

*** [[カクエリオキアミ]] ''Pseudeuphausia latifrons'' |

|||

** [[スティロケイロン属]] {{snamei||Stylocheiron}} - 12種 |

|||

*** [[ヒゲブトテナガオキアミ]] ''Stylocheiron carinatum'' |

|||

** [[テッサラブラキオン属]] {{snamei||Tessarabrachion}} - 1種 |

|||

** [[チサノエッサ属]] ''Thysanoessa'' - 10種 |

|||

*** [[ノコギリテナガオキアミ]] ''Thysanoessa gregaria'' |

|||

*** [[トゲホクヨウオキアミ]] (シャコタンオキアミ) ''Thysanoessa inermis'' |

|||

** [[チサノポーダ属]] {{snamei||Thysanopoda}} - 14種 |

|||

*** [[マルエリオキアミ]] ''Thysanopoda obtusifrons'' |

|||

*** [[ミツツノオキアミ]] ''Thysanopoda tricuspida'' |

|||

* '''ソコオキアミ科''' Bentheuphausiidae - 1属1種 |

|||

釣りえさ用として販売されているオキアミの食用は、控えるべきである。原料鮮度や製造過程の衛生管理が食品加工法規の適用外であり、また食品に適さない薬品が添加されている可能性もあるからである。 |

|||

** '''ソコオキアミ属''' ''Bentheuphausia'' |

|||

*** [[ソコオキアミ]] {{snamei||Bentheuphausia amblyops}} |

|||

== 分布 == |

|||

[[ドコサヘキサエン酸|DHA]]・EPA・[[アスタキサンチン]]の摂取を目的に南極オキアミから採取した油脂'''クリルオイル''' |

|||

世界中の海域に分布し、多くの種は特定の地域の沿岸の[[固有種]]である。ソコオキアミは世界中の深海に分布する[[汎存種]]である<ref>{{cite journal|author1=J. J. Torres|author2=J. J. Childress|year=1985|title=Respiration and chemical composition of the bathypelagic euphausiid ''Bentheuphausia amblyops''|journal=[[w:Marine Biology (journal)|Marine Biology]]|volume=87|issue=3|pages=267–272|doi=10.1007/BF00397804|s2cid=84486097}}</ref>。チサノエッサ属は[[大西洋]]と[[太平洋]]に分布する<ref>{{cite WoRMS |author=Volker Siegel |year=2024 |title=''Thysanoessa'' Brandt, 1851 |id=110679 |access-date=2024-12-07}}</ref>。ツノナシオキアミは太平洋に分布する。Northern krillは[[地中海]]から大西洋にかけて分布する。''Nyctiphanes'' 属の4種は沿岸域に分布する<ref name=damato>{{Cite journal|last=D’Amato|first=M. Eugenia|last2=Harkins|first2=Gordon W.|last3=de Oliveira|first3=Tulio|last4=Teske|first4=Peter R.|last5=Gibbons|first5=Mark J.|date=2008-08|title=Molecular dating and biogeography of the neritic krill Nyctiphanes|url=http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00227-008-1005-0|journal=Marine Biology|volume=155|issue=2|pages=243–247|language=en|doi=10.1007/s00227-008-1005-0|issn=0025-3162}}</ref>。[[カリフォルニア海流]]、[[フンボルト海流]]、[[ベンゲラ海流]]、[[カナリア海流]]の[[湧昇]]域に非常に豊富である<ref>{{cite web |author=Volker Siegel |year=2024 |title=''Nyctiphanes'' Sars, 1883 |editor=V. Siegel |work=World Euphausiacea database |publisher=[[World Register of Marine Species]] |url=http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=110677 |access-date=2024-12-07}}</ref><ref name="mauchline"/><ref name="gut2005">{{cite journal|author1=Jaime Gómez-Gutiérrez|author2=Carlos J. Robinson|year=2005|title=Embryonic, early larval development time, hatching mechanism and interbrood period of the sac-spawning euphausiid ''Nyctiphanes simplex'' Hansen|journal=Journal of Plankton Research|volume=27|issue=3|pages=279–295|doi=10.1093/plankt/fbi003|doi-access=free}}</ref>。コオリオキアミは[[南極大陸]]の沿岸に固有である<ref name="jarman2002">{{cite journal |author1=S. N. Jarman |author2=N. G. Elliott |author3=S. Nicol |author4=A. McMinn |year=2002 |title=Genetic differentiation in the Antarctic coastal krill ''Euphausia crystallorophias'' |journal=[[w:Heredity (journal)|Heredity]] |volume=88 |pages=280–287 |pmid=11920136 |doi=10.1038/sj.hdy.6800041 |issue=4|doi-access=free }}</ref>。その他にも {{snamei||Nyctiphanes capensis}} はベンゲラ海流に<ref name="damato"/>、{{snamei||Euphausia mucronata}} はフンボルト海流に<ref name="escribano">{{cite journal |author1=R. Escribano |author2=V. Marin |author3=C. Irribarren |year=2000 |title=Distribution of ''Euphausia mucronata'' at the upwelling area of Peninsula Mejillones, northern Chile: the influence of the oxygen minimum layer |journal=Scientia Marina |volume=64 |issue=1 |pages=69–77 |url=http://scientiamarina.revistas.csic.es/index.php/scientiamarina/article/viewFile/741/758 |doi=10.3989/scimar.2000.64n169|doi-access=free }}</ref>、オキアミ属の6種は[[南極海]]に固有である。 |

|||

を原料として製造される健康食品もある。 |

|||

南極からは7種が知られており<ref>{{cite web |author=P. Brueggeman |url=http://www.peterbrueggeman.com/nsf/fguide/arthropoda10.html |title=''Euphausia crystallorophias'' |work=Underwater Field Guide to Ross Island & McMurdo Sound, Antarctica |publisher=University of California, San Diego |accessdate=2008-05-11|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080511171653/http://www.peterbrueggeman.com/nsf/fguide/arthropoda10.html |archive-date=2008-05-11}}</ref>、チサノエッサ属の {{snamei||Thysanoessa macrura}}、オキアミ属の6種が知られる。ナンキョクオキアミは一般に水深100mに生息し<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.marinebio.org/species/krill/euphausia-superba/ |title=Krill, ''Euphausia superba'' |publisher=MarineBio.org |access-date=2024-12-07}}</ref>、コオリオキアミは通常水深300-600m、最大4,000mに生息する<ref>{{cite journal |author=J. A. Kirkwood |title=A Guide to the Euphausiacea of the Southern Ocean |journal=ANARE Research Notes |year=1984 |volume=1 |pages=1–45}}</ref>。大群で{{仮リンク|日周鉛直移動|en|Diel vertical migration}}を行い、音響測定によると水深400mまで移動することが分かっている<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Bianchi |first1=Daniele |last2=Mislan |first2=K.A.S. |title=Global patterns of diel vertical migration times and velocities from acoustic data |journal=Limnology and Oceanography |date=January 2016 |volume=61 |issue=1 |doi=10.1002/lno.10219|doi-access=free }}</ref>。ナンキョクオキアミとコオリオキアミはともに[[南緯55度線]]以南に分布し、コオリオキアミは[[南緯74度線]]以南で[[優占]]しており<ref>{{cite journal |author1=A. Sala |author2=M. Azzali |author3=A. Russo |url=http://www.icm.csic.es/scimar/download.php/Cd/c6d5ca7c8572ce508582edcd1793cf93/IdArt/3031 |title=Krill of the Ross Sea: distribution, abundance and demography of ''Euphausia superba'' and ''Euphausia crystallorophias'' during the Italian Antarctic Expedition (January–February 2000) |journal=Scientia Marina |volume=66 |issue=2 |pages=123–133 |year=2002 |doi=10.3989/scimar.2002.66n2123|doi-access=free }}</ref>、[[流氷]]域にも分布する。その他にも {{snamei||Euphausia frigida}}、{{snamei||Euphausia longirostris}}、{{snamei||Euphausia triacantha}}、{{snamei||Euphausia vallentini}} などの種が南極海に分布する<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Hosie|first=G.W|last2=Fukuchi|first2=M|last3=Kawaguchi|first3=S|date=2003-08|title=Development of the Southern Ocean Continuous Plankton Recorder survey|url=https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0079661103001320|journal=Progress in Oceanography|volume=58|issue=2-4|pages=263–283|language=en|doi=10.1016/j.pocean.2003.08.007}}</ref>。 |

|||

[[カップヌードル]]の具材に使われるエビがオキアミであるとされることがあるが、使用されているのは[[プーバラン]]である。 |

|||

== |

== 形態 == |

||

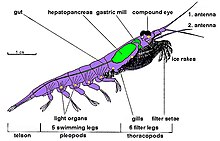

[[File:Krillanatomykils.jpg|thumb|ナンキョクオキアミの解剖学的特徴]] |

|||

=== オキアミ科 Euphausiidae === |

|||

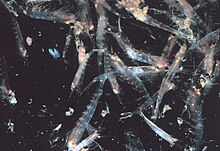

[[File:Euphausia gills.jpg|thumb|鰓は外部から見える]] |

|||

[[オキアミ科]] {{sname||Euphausiidae}} |

|||

* [[オキアミ属]] ''{{sname||Euphausia}}''<!-- |

|||

他の甲殻類と同様に、[[キチン質]]から成る[[外骨格]]を持つ。外見的には遊泳生の[[エビ]]類によく似ており、[[頭胸部]]は背甲に覆われ、腹部は6節からなる腹節と尾節からなる。腹部には10本の遊泳脚と[[尾扇]]がある。胸部には8節があり、それぞれに附属肢があるが、エビを含む[[十脚類]]ではその前3対が顎脚となっているのに対して、オキアミ類ではそのような変形が見られない。第2,第3節が鋏脚として発達する例や、最後の1-2対が退化する例もある。それらの胸部附属肢の基部の節には外に向けて発達した樹枝状の鰓がある。これが背甲に覆われないのもエビ類との違いである。よく似た[[アミ目]]とは胸脚の基部に鰓がないこと、尾肢に[[平衡胞]]がある点などで区別される。分類上はアミ目はフクロエビ上目とされ、系統的にもやや遠いと考えられている。2本の触角と、数対の胸脚を持つ。胸脚の数は属や種によって異なる。胸脚には摂食の為の脚と、体の手入れのための脚が含まれる。十脚目と共通して遊泳脚を持っており、これは[[ロブスター]]や[[ザリガニ]]のものと類似している。このためオキアミは十脚目の姉妹群と考えられることがある。 |

|||

** ''Euphausia americana'' |

|||

** ''Euphausia brevis''--> |

|||

外殻はほとんどの種で透明である。複雑な[[複眼]]を持ち、一部の種は色素を遮蔽することでさまざまな照度に適応している<ref>{{cite web |author=E. Gaten |url=http://www.le.ac.uk/biology/gat/northernkrill.html |title=''Meganyctiphanes norvegica'' |access-date=2009-02-25 |publisher=University of Leicester |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090701132500/http://www.le.ac.uk/biology/gat/northernkrill.html |archive-date=2009-07-01 }}</ref>。ほとんどのオキアミは成体でも約1-2cmで、いくつかの種は6-15cmに成長する。最大種である {{snamei||Thysanopoda cornuta}} は外洋の深海に生息する<ref>{{cite journal |author=E. Brinton |title=''Thysanopoda spinicauda'', a new bathypelagic giant euphausiid crustacean, with comparative notes on ''T. cornuta'' and ''T. egregia'' |journal=Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences |volume=43 |pages=408–412 |year=1953}}</ref>。外部から見える鰓によって、他の甲殻類と簡単に区別できる<ref name="tafi2008">{{cite web |publisher=Tasmanian Aquaculture & Fisheries Institute |url=http://www.tafi.org.au/zooplankton/imagekey/malacostraca/euphausiacea/ |title=Euphausiacea |access-date=2010-06-06 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090930075356/http://www.tafi.org.au/zooplankton/imagekey/malacostraca/euphausiacea/ |archive-date=2009-09-30}}</ref>。 |

|||

** [[コオリオキアミ]] ''Euphausia crystallorophias''<!-- |

|||

** ''Euphausia diomedeae'' |

|||

ソコオキアミは発光しないが、オキアミ科は[[発光器]]を持ち、[[生物発光]]を行う。[[ルシフェリン]]が[[ルシフェラーゼ]]によって活性化され、[[酵素]]を[[触媒]]とした[[化学発光]]が起こる。研究によると多くのオキアミのルシフェリンは、[[渦鞭毛藻]]のルシフェリンに似ているが異なる蛍光[[ポリピロール|テトラピロール]]であり<ref>{{cite journal |author=O. Shimomura |pmid=7676855 |title=The roles of the two highly unstable components F and P involved in the bioluminescence of euphausiid shrimps |journal=Journal of Bioluminescence and Chemiluminescence |volume=10 |issue=2 |pages=91–101 |year=1995 |doi=10.1002/bio.1170100205|doi-access= }}</ref>、オキアミはおそらくこの物質を渦鞭毛藻を含む食事から獲得している<ref>{{cite journal |author1=J. C. Dunlap |author2=J. W. Hastings |author3=O. Shimomura |year=1980 |title=Crossreactivity between the light-emitting systems of distantly related organisms: novel type of light-emitting compound |journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences |volume=77 |issue=3 |pages=1394–1397 |doi=10.1073/pnas.77.3.1394 |pmid=16592787 |jstor=8463 |pmc=348501|bibcode=1980PNAS...77.1394D |doi-access=free }}</ref>。オキアミの発光器は[[レンズ]]と焦点を合わせる能力を備えた複雑な器官であり、筋肉によって回転させることができる<ref>{{cite book |author1=P. J. Herring |author2=E. A. Widder |chapter-url=http://www.isbc.unibo.it/Files/BC_PlanktonNekton.htm |chapter=Bioluminescence in Plankton and Nekton |editor1=J. H. Steele |editor2=S. A. Thorpe |editor3=K. K. Turekian |title=Encyclopedia of Ocean Science |volume=1 |pages=[https://archive.org/details/encyclopediaofoc0000unse/page/308 308–317] |publisher=Academic Press, San Diego |year=2001 |isbn=978-0-12-227430-5 |url-access=registration |url=https://archive.org/details/encyclopediaofoc0000unse/page/308 }}</ref>。これらの器官の正確な機能は未だ不明だが、繁殖など他個体との相互作用、方向感覚の調節、[[カウンターシェーディング]]などの機能が考えられる<ref>{{cite conference|author1=S. M. Lindsay |author2=M. I. Latz |title=Experimental evidence for luminescent countershading by some euphausiid crustaceans |conference=American Society of Limnology and Oceanography (ASLO) Aquatic Sciences Meeting |location=Santa Fe |year=1999}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Sönke Johnsen |title=The Red and the Black: bioluminescence and the color of animals in the deep sea |journal=Integrative and Comparative Biology |volume=4 |issue=2 |pages=234–246 |year=2005 |url=http://www.biology.duke.edu/johnsenlab/pdfs/pubs/blcolor.pdf |doi=10.1093/icb/45.2.234 |pmid=21676767 |s2cid=247718 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20051002164113/http://www.biology.duke.edu/johnsenlab/pdfs/pubs/blcolor.pdf |archive-date=2005-10-02 |doi-access=free }}</ref>。 |

|||

** ''Euphausia distinguenda'' |

|||

** ''Euphausia eximia'' |

|||

== 生態系内の役割 == |

|||

** ''Euphausia fallax'' |

|||

=== 生物ポンプ === |

|||

** ''Euphausia frigida'' |

|||

[[File:Processes in the biological pump.webp|thumb|380x380px|生物ポンプの模式図。白枠内の数字は炭素フラックス(Gt C yr−1)、黒枠内の数字は炭素質量(Gt C)を表す<ref name=Cavan2019/>。]] |

|||

** ''Euphausia gibba'' |

|||

オキアミは[[生物ポンプ]]による[[炭素隔離#海洋隔離|海洋隔離]]の一端を担っており、まず植物プランクトンが大気から海洋表層に溶解した[[二酸化炭素]](90 Gt yr−1)を一時生産の過程で粒子状有機炭素(~ 50 Gt C yr−1)に変換する。その後植物プランクトンはオキアミや動物プランクトンに消費され、それらもさらに高次の捕食者によって消費される。残った植物プランクトンは凝集体を形成し、動物プランクトンの糞とともに急速に沈み、混合層から排出される(< 12 Gt C yr−1 14)。オキアミ、動物プランクトン、微生物は表層の植物プランクトンや深層の堆積粒子を消費し、呼吸によって有機炭素を[[溶存無機炭素]]である二酸化炭素に変換するため、表層で生成された炭素のうち、1000m以上の深海へ沈むものはごくわずかである。オキアミや小型の動物プランクトンは摂餌や排泄によって粒子を小さく断片化し、粒子状有機炭素の排出を遅らせる。これにより溶存有機炭素が細胞から直接、またはバクテリアの可溶化を介して間接的に放出される。その後細菌は溶存有機炭素を溶存無機炭素に再ミネラル化する。日周鉛直移動をするオキアミ、小型動物プランクトン、魚類は夜間に表層の溶存有機炭素を消費し、昼間に中深層で代謝することで、炭素を深層まで能動的に輸送する。能動輸送は生物の生態に応じて季節的に発生する可能性もある<ref name=Cavan2019/>。 |

|||

** ''Euphausia gibboides'' |

|||

** ''Euphausia hanseni'' |

|||

=== 食性 === |

|||

** ''Euphausia hemigibba'' |

|||

多くのオキアミは[[濾過摂食]]を行う<ref name="mauchline"/>。胸脚には細かい櫛があり、水を吸い込んで餌を濾過することができる。植物プランクトン、特に[[珪藻]]を餌とする種では非常に細かい。ほとんどが[[雑食性]]であるが<ref name="cripps">{{cite journal |author1=G. C. Cripps |author2=A. Atkinson |year=2000 |title=Fatty acid composition as an indicator of carnivory in Antarctic krill, ''Euphausia superba'' |journal=Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences |volume=57 |issue=S3 |pages=31–37 |doi=10.1139/f00-167}}</ref>、少数の種は[[肉食性]]で、動物プランクトンや[[仔魚]]を捕食する<ref name="saether">{{cite journal |author1=Olav Saether |author2=Trond Erling Ellingsen |author3=Viggo Mohr |year=1986 |title=Lipids of North Atlantic krill |journal=Journal of Lipid Research |volume=27 |pages=274–285 |pmid=3734626 |url=http://www.jlr.org/content/27/3/274.full.pdf |issue=3}}</ref>。[[食物連鎖]]の重要な要素であり、一次生産者である[[微細藻類]]を大型動物が食べられる形に変換している。Northern krillや他のいくつかの種は濾過器が比較的小さく、[[カイアシ類]]や大型の動物プランクトンを積極的に捕食する<ref name="saether"/>。直径5mm以下の[[マイクロプラスチック]]を消化し、分解して環境中に排出することができる<ref>{{cite journal|doi=10.1038/s41467-018-03465-9|pmid=29520086|pmc=5843626|title=Turning microplastics into nanoplastics through digestive fragmentation by Antarctic krill|journal=Nature Communications|volume=9|issue=1|pages=1001|year=2018|last1=Dawson|first1=Amanda L|last2=Kawaguchi|first2=So|last3=King|first3=Catherine K|last4=Townsend|first4=Kathy A|last5=King|first5=Robert|last6=Huston|first6=Wilhelmina M|last7=Bengtson Nash|first7=Susan M|bibcode=2018NatCo...9.1001D}}</ref>。 |

|||

** ''Euphausia krohnii'' |

|||

** ''Euphausia lamelligera'' |

|||

=== 天敵 === |

|||

** ''Euphausia longirostris'' |

|||

魚や[[ペンギン]]のような小型動物から[[アザラシ]]や[[ヒゲクジラ]]のような大型動物まで、多くの動物がオキアミを捕食する<ref name="noaa_krill">{{cite web |author=M. J. Schramm |url=http://sanctuaries.noaa.gov/news/features/1007_krill.html |title=Tiny Krill: Giants in Marine Food Chain |publisher=NOAA National Marine Sanctuary Program |date=2007-10-10 |access-date=2024-12-07}}</ref>。生態系の撹乱によりオキアミの個体数が減少すると、広範囲に影響を及ぼす可能性がある。例えば1998年に[[ベーリング海]]で[[円石藻]]が大量発生した際<ref>{{cite web |author=J. Weier |url=http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/Features/Coccoliths/bering_sea.php |title=Changing currents color the Bering Sea a new shade of blue |publisher=[[National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration|NOAA]] Earth Observatory |year=1999 |access-date=2024-12-07}}</ref>、珪藻の濃度が低下した。オキアミは小さな円石藻を食べることができないため、特にツノナシオキアミの個体数が急激に減少した。これにより他の種にも影響を及ぼし、[[ミズナギドリ]]の個体数が減少した。オキアミの減少はそのシーズンに[[サケ科|サケ]]が産卵しなかった理由の1つであると考えられている<ref>{{cite book |author1=R. D. Brodeur |author2=G. H. Kruse |author3=P. A. Livingston |author4=G. Walters |author5=J. Ianelli |author6=G. L. Swartzman |author7=M. Stepanenko |author8=T. Wyllie-Echeverria |title=Draft Report of the FOCI International Workshop on Recent Conditions in the Bering Sea |pages=22–26 |publisher=[[National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration|NOAA]] |year=1998}}</ref>。 |

|||

** ''Euphausia lucens'' |

|||

** ''Euphausia mucronata'' |

|||

[[寄生]]性の[[繊毛虫]]である {{snamei|Collinia}} 属はオキアミに感染し、感染した個体群を壊滅させる可能性がある。感染はベーリング海のトゲホクヨウオキアミや、北米太平洋岸沖のツノナシオキアミ、{{snamei||Thysanoessa spinifera}}、ノコギリテナガオキアミから報告されている<ref>{{cite news |author=J. Roach |url=http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2003/07/0717_030717_krillkiller.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20030724074903/http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2003/07/0717_030717_krillkiller.html |url-status=dead |archive-date=2003-07-24 |title=Scientists discover mystery krill killer |publisher=National Geographic News |date=2003-07-17}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author1=J. Gómez-Gutiérrez |author2=W. T. Peterson |author3=A. de Robertis |author4=R. D. Brodeur |title=Mass mortality of krill caused by parasitoid ciliates |journal=[[w:Science (journal)|Science]] |volume=301 |issue=5631 |page=339 |year=2003 |pmid=12869754 |doi=10.1126/science.1085164 |s2cid=28471713 }}</ref>。{{仮リンク|アミヤドリムシ科|en|Dajidae}}に寄生されることもある。{{snamei||Oculophryxus bicaulis}} は {{snamei||Stylocheiron affine}} や {{snamei||Stylocheiron longicorne}} の眼柄に付着し、頭部から血を吸うことが判明している。寄生されたオキアミは成熟しなかったことから、宿主の繁殖を阻害していると考えられる<ref>{{cite journal |author1=J. D. Shields |author2=J. Gómez-Gutiérrez |doi=10.1016/0020-7519(95)00126-3 |title=''Oculophryxus bicaulis'', a new genus and species of dajid isopod parasitic on the euphausiid ''Stylocheiron affine'' Hansen |journal=International Journal for Parasitology |volume=26 |issue=3 |pages=261–268 |year=1996|pmid=8786215 }}</ref>。気候変動もオキアミの個体群にとって脅威となっている<ref>{{cite news |author=Rusty Dornin |url=http://www.cnn.com/EARTH/9707/06/krill.kill/ |title=Antarctic krill populations decreasing |publisher=CNN |date=1997-07-06 |access-date=2011-06-18 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231014005627/http://www.cnn.com/EARTH/9707/06/krill.kill/ |archive-date=2023-10-14}}</ref>。 |

|||

** ''Euphausia mutica'' |

|||

** ''Euphausia nana''--> |

|||

== 生態と行動 == |

|||

** [[ツノナシオキアミ]] ''[[:en:Euphausia pacifica|Euphausia pacifica]]'' Pacific krill<!-- |

|||

[[File:Nauplius Hatching.jpg|thumb|ツノナシオキアミの孵化の様子]] |

|||

** ''Euphausia paragibba'' |

|||

** ''Euphausia pseudogibba'' |

|||

オキアミの生態は種によって若干の違いはあるものの、比較的よく理解されている<ref name="Gurney"/><ref name="mauchline">{{cite book|和書 |author1=J. Mauchline |author2=L. R. Fisher |year=1969 |title=The Biology of Euphausiids |series=Advances in Marine Biology |volume=7 |publisher=Academic Press |isbn=978-7-7708-3615-2}}</ref>。孵化した幼生は三対の附属肢を持つ[[ノープリウス]]であり、その後ほぼ体全体が背甲に覆われる[[メタノープリウス]]期、腹部が伸長したカリプトピス期、複眼が柄を持って突き出すフルシリア期を経て、附属肢が発達した成体となる。生息域によっても異なるが、成熟までに1-3年を要すると考えられている。卵嚢内に卵を産む種では、ノープリウスとメタノープリウスの間にpseudometanaupliusという独自の期間がある。成長と脱皮を繰り返し、小型個体は脱皮の頻度が高い。体内に蓄えられた[[卵黄]]により、メタノープリウス幼生は栄養を得る。 |

|||

** ''Euphausia recurva'' |

|||

** ''Euphausia sanzoi'' |

|||

カリプトピス期までに[[細胞分化]]が進み、口と消化管が発達し、植物プランクトンを食べ始める。その頃には卵黄が尽き、藻類の多い海洋表層に到達する。フルシリア期には最前部の節から遊泳脚を持つ節が生まれる。新しい遊泳脚は、次の脱皮時にのみ機能する。フルシリア期に追加される節の数は、環境条件に応じて同種であっても異なる場合がある<ref>{{cite journal |author=M. D. Knight |url=http://calcofi.org/publications/calcofireports/v25/Vol_25_Knight.pdf |title=Variation in larval morphogenesis within the Southern California Bight population of ''Euphausia pacifica'' from Winter through Summer, 1977–1978 |journal=CalCOFI Report |volume=XXV |year=1984 |access-date=2017-11-05 |archive-date=2019-08-03 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190803044000/http://www.calcofi.org/publications/calcofireports/v25/Vol_25_Knight.pdf |url-status=dead }}</ref>。フルシリア期を経て成体と同様の形となり、生殖腺が発達して[[性成熟]]する<ref name="fao_factsheet">{{cite web |publisher=[[Food and Agriculture Organization]] |url=http://www.fao.org/fishery/species/3393/en |work=Species factsheet |title=''Euphausia superba'' |access-date=2010-06-04 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211025070815/http://www.fao.org/fishery/species/3393/en |archive-date=2021-10-25}}</ref>。高緯度に生息するナンキョクオキアミのように6年以上生きるものもあれば、中緯度に生息するツノナシオキアミのように2年しか生きない種もある<ref name="nicol"/>。低緯度に生息する種の寿命はさらに短く、{{snamei||Nyctiphanes simplex}} の寿命は通常6-8ヶ月である<ref>{{cite journal|doi=10.3354/meps119063 |author=J. G. Gómez |title=Distribution patterns, abundance and population dynamics of the euphausiids''Nyctiphanes simplex'' and ''Euphausia eximia'' off the west coast of Baja California, Mexico |journal=Marine Ecology Progress Series |volume=119 |pages=63–76 |year=1995 |url=https://www.int-res.com/articles/meps/119/m119p063.pdf |bibcode=1995MEPS..119...63G |doi-access=free }}</ref>。 |

|||

** ''Euphausia sibogae'' |

|||

** ''Euphausia similis'' |

|||

=== 繁殖 === |

|||

** ''Euphausia spinifera''--> |

|||

[[File:Nematoscelis difficilis female.jpg|thumb|left|抱卵した{{snamei||Hansarsia difficilis}}。卵の直径は0.3–0.4mm。]] |

|||

** [[ナンキョクオキアミ]] ''Euphausia superba'' Antarctic krill<!-- |

|||

** ''Euphausia tenera'' |

|||

繁殖期は種や気候によって異なり、一般に雄は雌の第6胸脚の基部にある生殖孔に[[精莢]]を産み付ける。侵入した[[精子]]は一時的に貯精嚢に蓄えられる。雌は卵巣に数千個の卵子を持ち、その量は体重の3分の1にもなる<ref>{{cite journal |author1=R. M. Ross |author2=L. B. Quetin |title=How productive are Antarctic krill? |journal=BioScience |volume=36 |issue=4 |pages=264–269 |year=1986 |doi=10.2307/1310217 |jstor=1310217}}</ref>。1回の繁殖期の間に複数回の繁殖を行うこともあり、その間隔は数日程度である<ref name="gut2005"/><ref name="cuzin">{{cite journal |author=Janine Cuzin-Roudy |year=2000 |title=Seasonal reproduction, multiple spawning, and fecundity in northern krill, ''Meganyctiphanes norvegica'', and Antarctic krill, ''Euphausia superba'' |journal=Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences |volume=57 |issue=S3 |pages=6–15 |doi=10.1139/f00-165}}</ref>。 |

|||

** ''Euphausia triacantha'' |

|||

** ''Euphausia vallentini''--> |

|||

2種類の産卵方法が知られている<ref name="gut2005"/>。ソコオキアミ、オキアミ属、''Meganyctiphanes'' 属、チサノエッサ属、チサノポーダ属の57種は「broadcast spawners (放出産卵)」であり、雌が[[受精卵]]を水中に放出し、卵は通常沈んで分散する。これらの種は通常ノープリウス期で孵化するが、メタノープリウス期やカリプトピス期で孵化する例も発見されている<ref>{{cite journal |author=J. Gómez-Gutiérrez |title=Hatching mechanism and delayed hatching of the eggs of three broadcast spawning euphausiid species under laboratory conditions |journal=Journal of Plankton Research |volume=24 |issue=12 |pages=1265–1276 |year=2002 |doi=10.1093/plankt/24.12.1265|doi-access=free }}</ref>。残りの29種は「sac spawners (嚢産卵)」であり、雌が卵を胸脚の一部が広がった抱卵肢に付着させてメタノープリウス期に孵化するまで運ぶが、''Hansarsia difficilis'' などの一部の種はノープリウス期またはpseudometanauplius期に孵化することもある<ref>{{cite book |author1=E. Brinton |author2=M. D. Ohman |author3=A. W. Townsend |author4=M. D. Knight |author5=A. L. Bridgeman |url=http://species-identification.org/species.php?species_group=euphausiids&menuentry=inleiding |title=Euphausiids of the World Ocean |publisher=World Biodiversity Database CD-ROM Series, Springer Verlag |year=2000 |isbn=978-3-540-14673-5 |access-date=4 December 2009 |archive-date=26 February 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120226200322/http://species-identification.org/species.php?species_group=euphausiids&menuentry=inleiding |url-status=dead }}</ref>。 |

|||

* ''Meganyctiphanes'' |

|||

** ''Meganyctiphanes norvegica'' [[:en:Northern krill|Northern krill]] |

|||

=== 脱皮 === |

|||

* ''Nematobrachion''<!-- |

|||

外骨格よりも大きく成長し、窮屈になると[[脱皮]]する。若い個体は成長が早く、大型個体よりも頻繁に脱皮する。脱皮の頻度は種によって大きく異なり、同じ種の中でも緯度、水温、餌の入手可能性など多くの外的要因の影響を受ける。亜熱帯の種である {{snamei||Nyctiphanes simplex}} は、脱皮間隔が2-7日である。幼生は平均4日ごとに脱皮し、幼体と成体は平均6日ごとに脱皮する。南極海に生息するナンキョクオキアミでは、脱皮間隔は-1から4℃の水温に応じて9-28日であることが観察されており、[[北海]]に生息する {{snamei||Meganyctiphanes norvegica}} でも脱皮間隔は9-28日であるが、水温は2.5-15℃である<ref>{{cite journal|author=F. Buchholz|year=2003|title=Experiments on the physiology of Southern and Northern krill, ''Euphausia superba'' and ''Meganyctiphanes norvegica'', with emphasis on moult and growth – a review|journal=Marine and Freshwater Behaviour and Physiology|volume=36|issue=4|pages=229–247|bibcode=2003MFBP...36..229B|doi=10.1080/10236240310001623376|s2cid=85121989}}</ref>。ナンキョクオキアミは餌が足りないときには体の大きさを小さくすることができ、外骨格が大きくなりすぎると脱皮する<ref>{{cite journal |author1=H.-C. Shin |author2=S. Nicol |title=Using the relationship between eye diameter and body length to detect the effects of long-term starvation on Antarctic krill ''Euphausia superba'' |journal=Marine Ecology Progress Series |volume=239 |pages=157–167 |year=2002 |doi=10.3354/meps239157|bibcode=2002MEPS..239..157S |doi-access=free }}</ref>。同様の能力は、極地から温帯にかけての太平洋に生息するツノナシオキアミでも、高水温への適応として観察されている。他の温帯のオキアミにも同様の能力があると予測されている<ref>{{cite journal |author1=B. Marinovic |author2=M. Mangel |url=http://people.ucsc.edu/~msmangel/MM.pdf |title=Krill can shrink as an ecological adaptation to temporarily unfavourable environments |journal=Ecology Letters |volume=2 |pages=338–343 |year=1999}}</ref>。 |

|||

** ''Nematobrachion boopis'' |

|||

** ''Nematobrachion flexipes'' |

|||

=== 群れ === |

|||

** ''Nematobrachion sexspinosus''--> |

|||

[[File:Krill swarm.jpg|thumb|群れ]] |

|||

* ''Nematoscelis''<!-- |

|||

** ''Nematoscelis atlantica'' |

|||

ほとんどのオキアミは[[群れ]]を作るが、その大きさと密度は種と地域によって異なる。ナンキョクオキアミの場合、群れの密度は1m<sup>3</sup>あたり10,000-60,000匹に達する<ref>{{cite book|author1=U. Kils |author2=P. Marshall |chapter=Der Krill, wie er schwimmt und frisst – neue Einsichten mit neuen Methoden ("''The Antarctic krill – how it swims and feeds – new insights with new methods''") |editor1=I. Hempel |editor2=G. Hempel |title=Biologie der Polarmeere – Erlebnisse und Ergebnisse (''Biology of the Polar Oceans Experiences and Results'') |publisher=Fischer Verlag|year=1995 |pages=201–210 |isbn=978-3-334-60950-7}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |author=R. Piper |title=Extraordinary Animals: An Encyclopedia of Curious and Unusual Animals |url=https://archive.org/details/extraordinaryani0000pipe |url-access=registration |publisher=[[w:Greenwood Press (publisher)|Greenwood Press]] |year=2007 |isbn=978-0-313-33922-6}}</ref>。群れを作ることは防御になり、小型の捕食者を混乱させる。2012年に発表された研究では、オキアミの群れの行動がモデル化され。他の個体の存在によって引き起こされる動き、摂餌、ランダムな移動が考慮された<ref name=kha2012>{{cite journal |first1=A.H. |last1= Gandomi |first2=A.H. |last2=Alavi |title= Krill Herd: A New Bio-Inspired Optimization Algorithm |journal= Communications in Nonlinear Science and Numerical Simulation |doi=10.1016/j.cnsns.2012.05.010|year=2012 |volume=17 |issue=12 |pages=4831–4845 |bibcode=2012CNSNS..17.4831G }}</ref>。群れが密集すると、特に水面近くでは魚、鳥、哺乳類の捕食者の間で餌を巡る激しい争いを引き起こす可能性がある。群れは襲撃されると散り散りになり、中には瞬時に脱皮し、殻を囮にする個体も観察されている<ref>{{cite web |author=D. Howard |url=http://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/explorations/02quest/background/krill/krill.html|title=Krill in Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary |publisher=National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration|access-date=2024-12-07}}</ref>。 |

|||

** ''Nematoscelis difficilis'' |

|||

** ''Nematoscelis gracilis'' |

|||

=== 移動 === |

|||

** ''Nematoscelis lobata'' |

|||

[[File:Pleopods euphausia superba.jpg|right|thumb|ナンキョクオキアミの遊泳]] |

|||

** ''Nematoscelis megalops'' |

|||

** ''Nematoscelis microps'' |

|||

日中は深海で過ごし、夜間に水面に浮上する{{仮リンク|日周鉛直移動|en|Diel vertical migration}}を行う。深く潜るほど活動は鈍くなるが<ref>{{cite journal |author1=J. S. Jaffe |author2=M. D. Ohmann |author3=A. de Robertis |url=http://jaffeweb.ucsd.edu/files/pubs/Sonar%20estimates%20of%20daytime%20activity%20levels%20of%20Euphausia%20pacifica%20in%20Saanich%20Inlet.pdf |title=Sonar estimates of daytime activity levels of ''Euphausia pacifica'' in Saanich Inlet |journal=Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences |volume=56 |pages=2000–2010 |year=1999 |doi=10.1139/cjfas-56-11-2000 |issue=11 |s2cid=228567512 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110720075623/http://jaffeweb.ucsd.edu/files/pubs/Sonar%20estimates%20of%20daytime%20activity%20levels%20of%20Euphausia%20pacifica%20in%20Saanich%20Inlet.pdf |archive-date=2011-07-20 }}</ref>、捕食者との遭遇を減らし、エネルギーを節約することができる。オキアミの遊泳活動は胃の満腹度によって変化する。水面で餌を食べた満腹のオキアミは泳ぎが鈍くなり、混合層の下に沈んでいく<ref>{{cite journal|author1=Geraint A. Tarling |author2=Magnus L. Johnson |year=2006 |title=Satiation gives krill that sinking feeling |journal=Current Biology |volume=16 |issue=3 |pages=83–84 |doi=10.1016/j.cub.2006.01.044 |pmid=16461267|doi-access=free }}</ref>。沈む際には排泄物を出すため、これが南極の炭素循環に関与している。胃が空のオキアミはより活発に泳ぐため、水面に向かう。垂直移動は1日に2-3回起こることがある。ナンキョクオキアミ、ツノナシオキアミ、{{snamei||Euphausia hanseni}}、カクエリオキアミ、{{snamei||Thysanoessa spinifera}} など一部の種は、捕食される危険が高いにもかかわらず、摂餌と繁殖の目的で日中に水面に群れを形成する<ref name="howard">{{cite book |author=Dan Howard |chapter=Krill|chapter-url=http://pubs.usgs.gov/circ/c1198/chapters/133-140_Krill.pdf |pages=133–140 |editor1=Herman A. Karl |editor2=John L. Chin |editor3=Edward Ueber |editor4=Peter H. Stauffer |editor5=James W. Hendley II |url=http://pubs.usgs.gov/circ/c1198/ |title=Beyond the Golden Gate – Oceanography, Geology, Biology, and Environmental Issues in the Gulf of the Farallones |publisher=United States Geological Survey |id=Circular 1198 |year=2001 |access-date=2011-10-08}}</ref>。[[アルテミア]]をモデルにした実験では、オキアミが集団で垂直移動することにより下向きの水流を作り出し、海洋の混合に大きな影響を与える可能性があることが示された<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Wishart|first=Skye|date=July–August 2018|title=The krill effect|url=https://www.nzgeo.com/stories/the-krill-effect/|journal=New Zealand Geographic|issue=152|pages=24}}</ref>。 |

|||

** ''Nematoscelis tenella''--> |

|||

* ''Nyctiphanes''<!-- |

|||

毎秒5-10cmの速度で泳ぎ<ref>{{cite journal |journal=ICES Journal of Marine Science |year=2005 |volume=62 |issue=1 |pages=25–32 |doi=10.1016/j.icesjms.2004.07.027 |title=New target-strength model indicates more krill in the Southern Ocean |author1=David A. Demer |author2=Stéphane G. Conti |doi-access=free }}</ref>、推進力として遊泳脚を使用する。より長い距離を移動すると海流の影響を受ける。脅威を感じると尾を振り回して比較的素早く水中を後進し、遊泳の10-27倍の速度に達する。ナンキョクオキアミのような大型種の場合、約0.8m/sに相当する<ref>{{cite journal|author=U. Kils|title=Swimming behavior, swimming performance and energy balance of Antarctic krill ''Euphausia superba''|url=http://ecoscope.com/biomass3.htm|journal=BIOMASS Scientific Series 3, BIOMASS Research Series|pages=1–122|year=1982|access-date=2017-11-11|archive-date=2020-06-02|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200602170105/http://ecoscope.com/biomass3.htm|url-status=dead}}</ref>。オキアミの遊泳能力から、多くの研究者は成体のオキアミを弱い流れに逆らって移動する[[ネクトン]]に分類している。幼生は一般に[[プランクトン]]とされる<ref>{{cite journal |author1=S. Nicol |author2=Y. Endo |url=http://www.fao.org/docrep/003/w5911e/w5911e00.htm |title=Krill Fisheries of the World |journal=FAO Fisheries Technical Paper |volume=367 |year=1997}}</ref>。 |

|||

** ''Nyctiphanes australis'' |

|||

** ''Nyctiphanes capensis'' |

|||

== 海洋循環における影響 == |

|||

** ''Nyctiphanes couchii'' |

|||

ナンキョクオキアミは[[生物地球化学的循環]]と<ref name=Cavan2019/><ref>Ratnarajah, L., Bowie, A.R., Lannuzel, D., Meiners, K.M. and Nicol, S. (2014) "The biogeochemical role of baleen whales and krill in Southern Ocean nutrient cycling". ''PLOS ONE'', '''9'''(12): e114067. {{doi|10.1371/journal.pone.0114067}}</ref>と南極の食物連鎖<ref>Hopkins, T.L., Ainley, D.G., Torres, J.J., Lancraft, T.M., 1993. Trophic structure in open waters of the Marginal Ice Zone in the Scotia Weddell Confluence region during spring (1983). Polar Biology 13, 389–397.</ref><ref>Lancraft, T.M., Relsenbichler, K.R., Robinson, B.H., Hopkins, T.L., Torres, J.J., 2004. A krill-dominated micronekton and macrozooplankton community in Croker Passage, Antarctica with an estimate of fish predation. Deep-Sea Research II 51, 2247–2260.</ref>において重要な種で、栄養素を循環させ、ペンギンやヒゲクジラ、シロナガスクジラに餌を供給する。 |

|||

** ''Nyctiphanes simplex''--> |

|||

* ''Pseudeuphausia''<!-- |

|||

=== 生物地球科学的循環における役割 === |

|||

** ''Pseudeuphausia latifrons'' |

|||

[[File:Role of Antarctic krill in biogeochemical cycles.webp|thumb|450x450px|生物地球科学的循環におけるナンキョクオキアミの役割を示した図]] |

|||

** ''Pseudeuphausia sinica''--> |

|||

* ''Stylocheiron''<!-- |

|||

オキアミは表層で植物プランクトンを食べ(図の①)、その一部が植物分解物の集合体として沈む(図の②)。これは簡単に分解されるため、水温躍層よりも下に沈まない可能性がある。オキアミは糞も放出し(図の③)、これは深海に沈むこともあるが、通常は沈む途中でオキアミ、バクテリア、動物プランクトンによって消費され、分解される(図の④)。氷縁域では糞がより深いところまで達することがある(図の⑤)。オキアミの脱皮殻は沈んで炭素フラックスに寄与する(図の⑥)。[[鉄]]や[[アンモニウム]]などの栄養素は、オキアミの摂餌や排泄に伴って放出される(図の⑦)。これが表層近くで放出されると、植物プランクトンの生成を刺激し、大気中の二酸化炭素のさらなる減少につながる可能性がある。成体のオキアミの中には、より深いところに生息し、深海にある有機物を食べるものもいる(図の⑧)。水温躍層の下に有機物または二酸化炭素の形で沈んだ炭素は、季節的な混合の影響を受けなくなり、少なくとも1年間は深海に貯蔵される(図の⑨)。成体のオキアミの回遊により、深海の栄養豊富な水が混合され(図の⑩)、一次生産がさらに刺激される。また成体のオキアミは海底で餌を探し、呼吸によって二酸化炭素を深海に放出し、底生捕食者に消費される可能性がある(図の⑪)。南極海の海氷の下に生息する幼生は、広範囲にわたる日中鉛直移動を行い(図の⑫)、水温躍層の下に二酸化炭素を移動させる可能性がある。ヒゲクジラを含む多くの捕食者に消費されるため(図の⑬)、オキアミの炭素の一部はクジラが死んで海底に沈み、深海生物に消費されるまでの数十年間、バイオマスとして貯蔵される<ref name=Cavan2019/>。 |

|||

** ''Stylocheiron abbreviatum'' |

|||

** ''Stylocheiron affine'' |

|||

=== 個体レベルの栄養素の循環 === |

|||

** ''Stylocheiron armatum'' |

|||

[[File:Cycling of nutrients by an individual krill.webp|thumb|個体内での栄養素の循環を示した図|320x320ピクセル]] |

|||

** ''Stylocheiron carinatum'' |

|||

** ''Stylocheiron elongatum'' |

|||

オキアミは脱皮時に、溶解した[[カルシウム]]、[[フッ化物]]、[[リン]]を[[外骨格]]から放出する(図の①)。外骨格を形成する[[キチン]]は有機物であり、深海の沈降粒子フラックスに寄与する。オキアミは植物プランクトンや他の動物を消費して得たエネルギーの一部を呼吸によって二酸化炭素に変換する(図の②)。中深層から大群で水面まで泳ぐとき(図の③)、栄養分の少ない表層水に栄養をもたらす可能性があり、アンモニウムと[[リン酸]]が鰓から放出され、排泄の際には溶解した有機炭素、[[窒素]]、[[尿素]]、[[リン]](DOC、DON、DOP)が放出される(図の②および④)。粒子状の有機炭素、窒素、リン(POC、PON、POP)と鉄を含む沈みやすい糞を放出する。鉄はDOC、DON、DOP とともに周囲の水に浸出すると生体利用が可能になる(図の⑤)<ref name=Cavan2019>Cavan, E.L., Belcher, A., Atkinson, A., Hill, S.L., Kawaguchi, S., McCormack, S., Meyer, B., Nicol, S., Ratnarajah, L., Schmidt, K. and Steinberg, D.K. (2019) "The importance of Antarctic krill in biogeochemical cycles". ''Nature communications'', '''10'''(1): 1–13. {{doi|10.1038/s41467-019-12668-7}}. [[File:CC-BY icon.svg|50px]] Material was copied from this source, which is available under a [https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License].</ref>。 |

|||

** ''Stylocheiron indicus'' |

|||

** ''Stylocheiron insulare'' |

|||

== 人との関わり == |

|||

** ''Stylocheiron longicorne'' |

|||

=== 漁業の歴史 === |

|||

** ''Stylocheiron maximum'' |

|||

[[File:Krillmeatkils.jpg|thumb|冷凍されたナンキョクオキアミ]] |

|||

** ''Stylocheiron microphthalma'' |

|||

** ''Stylocheiron robustum'' |

|||

オキアミは少なくとも19世紀から人間や家畜の食料として採取されてきたが、日本ではおそらくそれ以前から知られていた。大規模な漁業は1960年代後半から1970年代前半にかけて発展し、現在は南極海と日本近海でのみ行われている。歴史的にオキアミ漁業が盛んな国は日本と[[ソ連]]、ソ連崩壊後は[[ロシア]]と[[ウクライナ]]であった<ref name="pri">{{cite web|author1=Grossman, Elizabeth|title=Scientists consider whether krill need to be protected from human over-hunting|url=https://www.pri.org/stories/2015-07-14/scientists-consider-whether-krill-need-be-protected-human-over-hunting|publisher=Public Radio International (PRI)|access-date=2024-12-07|date=2015-07-14}}</ref>。漁獲量がピークを迎えた1983年には南極海だけで約52万8千トン(うちソ連が93%を漁獲)が漁獲され、現在は乱獲防止のために管理されている<ref>{{cite web|title=Krill fisheries and sustainability: Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba)|url=https://www.ccamlr.org/en/fisheries/krill-fisheries-and-sustainability|publisher=Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources|access-date=2024-12-07|date=2015-04-23}}</ref>。1993年、ロシアがオキアミ漁業から撤退したことと、{{仮リンク|南極の海洋生物資源の保存に関する委員会|en|Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources}}がナンキョクオキアミの持続可能な利用のために最大漁獲量を定めたことにより、オキアミ漁業は衰退した。2011年10月の見直しの後、委員会は漁獲量を変更しないことを決定した<ref name=nature/>。南極での年間漁獲量は10万トン前後で安定しており、これは委員会の漁獲割当量のおよそ50分の1に相当する<ref name=ccamlr/>。おそらくコストの高さと政治的および法的問題により、漁獲量は制限されている<ref>{{cite journal|author=Minturn J. Wright |title=The Ownership of Antarctica, its Living and Mineral Resources |journal=Journal of Law and the Environment |year=1987 |volume=4 |issue=2 |pages=49–78 |url=http://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/jlen4&div=14&collection=journals&set_as_cursor=0&men_tab=srchresults}}</ref>。日本の漁業は約7万トンで飽和状態になった<ref name="nicol2">{{cite journal |author1=S. Nicol |author2=J. Foster |title=Recent trends in the fishery for Antarctic krill |journal=Aquatic Living Resources |volume=16 |pages=42–45 |year=2003 |doi=10.1016/S0990-7440(03)00004-4|url=http://www.alr-journal.org/10.1016/S0990-7440(03)00004-4/pdf }}</ref>。オキアミは世界中に生息しているが、南極海では個体数が豊富で漁獲しやすいため、操業が好まれている。南極海のオキアミは「クリーンな製品」とみなされている<ref name=pri/>。2018年には、南極で操業しているほぼ全てのオキアミ漁会社が、ペンギンの繁殖コロニー周辺を含む南極半島周辺の広大な海域での操業を2020年から中止すると発表した<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.independent.co.uk/environment/antarctica-krill-fishing-industry-marine-protected-zone-greenpeace-whales-seals-penguins-a8439311.html|title=Krill fishing industry backs massive Antarctic ocean sanctuary to protect penguins, seals and whales|last=Josh|first=Gabbatiss|date=2018-07-10|work=The Independent|access-date=2024-12-07}}</ref>。 |

|||

** ''Stylocheiron suhmii''--> |

|||

* ''Tessarabrachion''<!-- |

|||

=== 消費 === |

|||

** ''Tessarabrachion oculatus''--> |

|||

[[File:08634jfPamarawan, Malolos City, Bulacan River Districtfvf 27.jpg|thumb|バゴーンの材料となる乾燥した発酵オキアミ]] |

|||

* ''Thysanoessa''<!-- |

|||

** ''Thysanoessa gregaria'' |

|||

ナンキョクオキアミの総バイオマス量は4億トンにも達するが、この[[キーストーン種]]に対する人間の影響は増大しており、2010年から2014年にかけて総漁獲量は39%増加して294,000トンとなった。オキアミの漁獲を行う主な国は、[[ノルウェー]](2014年の総漁獲量の56%)、[[韓国]](19%)、[[中国]](18%)である<ref name="ccamlr">{{cite web|title=Krill – biology, ecology and fishing|url=https://www.ccamlr.org/en/fisheries/krill-%E2%80%93-biology-ecology-and-fishing|publisher=Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources|access-date=2024-12-07|date=2015-04-28}}</ref>。 |

|||

** ''Thysanoessa inspinata'' |

|||

** ''Thysanoessa longicaudata'' |

|||

漁獲されたオキアミは未加工もしくは[[フリーズドライ]]加工され、または粉末状で販売され、養殖漁業の飼料用、[[釣り餌]]、観賞魚の餌などに利用される。飼料としてのオキアミには、魚の耐病性向上や、観賞魚の体色の発色向上などの効果があって人気が高い。日本では[[ナンキョクオキアミ]]の34%、[[ツノナシオキアミ]]の50%が魚の飼料として消費される。また日本では70年代に海釣りの撒きえさとして導入され、[[黒鯛]]や[[メジナ]]、また[[サビキ釣り]]のテクニックに革命を起こした。ナンキョクオキアミの4分の1、ツノナシオキアミの半分は釣りえさ用である。オキアミは[[タンパク質]]と[[ω-3脂肪酸]]を豊富に含んでおり、21世紀初頭からは人間の食料、オイルカプセルなどの[[サプリメント]]、家畜の餌、[[ペットフード]]として開発が進められている<ref name=pri/><ref name="nature">{{cite journal|pmid=20811427|year=2010|last=Schiermeier|first=Q|title=Ecologists fear Antarctic krill crisis|journal=Nature|volume=467|issue=7311|pages=15|doi=10.1038/467015a|doi-access=free}}</ref><ref name="noaa">{{cite web|url=https://swfsc.noaa.gov/textblock.aspx?Division=AERD&id=11462|title=Why krill?|publisher=Southwest Fisheries Science Center, US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration|date=2016-11-22|access-date=2017-04-01|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200803051943/https://swfsc.noaa.gov/textblock.aspx?Division=AERD&id=11462 |archive-date=2020-08-03}}</ref>。 |

|||

** ''Thysanoessa longipes'' |

|||

** ''Thysanoessa macrura'' |

|||

[[魚肉ソーセージ]]など[[加工食品]]の原料にもなり<ref>{{Cite web|和書|url=https://mdinfo.jccu.coop/bb/shohindetail/4902220146468/psspu:013553 |title=コープ商品検索トップ > 惣菜・デイリー > 魚肉ソーセージ > チルドおさかなソーセージ 8本入(160g) |access-date=2022-12-25 |publisher=coop}}</ref>、また調味料として塩辛も作られている。これは朝鮮半島や日本で[[キムチ]]の[[発酵]]に[[アキアミ]]の塩辛同様に使われる事がある<ref>[http://www.bingotukemono.jp/blog/489.html 吉野家白菜キムチ 200g - キムチ、大根のお漬物なら備後漬物株式会社]</ref>。以前は漁獲後の劣化が早く風味落ちがするため、人間の食用としての消費はきわめて少なかったが、近年加工技術の進化により、ツノナシオキアミは[[サクラエビ]]の安価な代用品として[[お好み焼き]]などに利用されている。オキアミは塩辛く、エビよりも魚の風味がやや強い。市販の製品として大量に消費するためには、食べられない殻を剥く必要がある<ref name=noaa/>。釣りえさ用として販売されているオキアミの食用は、控えるべきである。原料鮮度や製造過程の衛生管理が食品加工法規の適用外であり、また食品に適さない薬品が添加されている可能性もあるからである。 |

|||

** ''Thysanoessa parva'' |

|||

** ''Thysanoessa raschii'' |

|||

[[ドコサヘキサエン酸|DHA]]・EPA・[[アスタキサンチン]]の摂取を目的に南極オキアミから採取した油脂'''クリルオイル'''を原料として製造される健康食品もある。2011年、[[アメリカ食品医薬品局]]は、製造されたクリルオイル製品が人間の消費に安全であると発表した<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.fda.gov/Food/IngredientsPackagingLabeling/GRAS/NoticeInventory/ucm267323.htm |publisher=US FDA |author=Cheeseman MA |date=2011-07-22 |title=Krill oil: Agency Response Letter GRAS Notice No. GRN 000371 |access-date=2015-06-03 |archive-date=2017-03-10 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171031011417/https://www.fda.gov/Food/IngredientsPackagingLabeling/GRAS/NoticeInventory/ucm267323.htm}}</ref>。 |

|||

** ''Thysanoessa spinifera'' |

|||

** ''Thysanoessa vicina''--> |

|||

オキアミを含む小型甲殻類は[[東南アジア]]で最も広く消費されており、殻付きのまま[[発酵]]させ、細かく挽いて[[シュリンプペースト]]を作ることが多い。炒めて[[白米]]と一緒に食べたり、様々な伝統料理に[[うま味]]を加えるために使用したりする<ref>{{cite journal |last=Omori |first=M. |title=Zooplankton fisheries of the world: A review |journal=Marine Biology |date=1978 |volume=48 |issue=3 |pages=199–205 |doi=10.1007/BF00397145|s2cid=86540101 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Pongsetkul |first1=Jaksuma |last2=Benjakul |first2=Soottawat |last3=Sampavapol |first3=Punnanee |last4=Osako |first4=Kazufumi |last5=Faithong |first5=Nandhsha |title=Chemical composition and physical properties of salted shrimp paste (Kapi) produced in Thailand |journal=International Aquatic Research |date=17 September 2014 |volume=6 |issue=3 |pages=155–166 |doi=10.1007/s40071-014-0076-4|doi-access=free }}</ref>。発酵過程で得られる液体は[[魚醤]]としても使用される<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Abe |first1=Kenji |last2=Suzuki |first2=Kenji |last3=Hashimoto |first3=Kanehisa |title=Utilization of Krill as a Fish Sauce Material |journal=Nippon Suisan Gakkaishi |date=1979 |volume=45 |issue=8 |pages=1013–1017 |doi=10.2331/suisan.45.1013|doi-access=free }}</ref>。[[カップヌードル]]の具材に使われるエビがオキアミであるとされることがあるが、使用されているのは[[プーバラン]]である。 |

|||

* ''Thysanopoda''<!-- |

|||

** ''Thysanopoda acutifrons'' |

|||

** ''Thysanopoda aequalis'' |

|||

** ''Thysanopoda astylata'' |

|||

** ''Thysanopoda cornuta'' |

|||

** ''Thysanopoda cristata'' |

|||

** ''Thysanopoda egregia'' |

|||

** ''Thysanopoda microphthalma'' |

|||

** ''Thysanopoda minyops'' |

|||

** ''Thysanopoda monacantha'' |

|||

** ''Thysanopoda obtusifrons'' |

|||

** ''Thysanopoda orientalis'' |

|||

** ''Thysanopoda pectinata'' |

|||

** ''Thysanopoda spinicaudata'' |

|||

** ''Thysanopoda tricuspida''--> |

|||

=== 食料以外での利用 === |

|||

=== ソコオキアミ科 Bentheuphausiidae === |

|||

オキアミは中程度の[[レイノルズ数]]の領域で機敏に泳ぐが、この領域では無人水中ロボットの移動が難しく、オキアミの移動を研究することで、水中ロボットの設計に応用する試みが進められている<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Oliveira Santos |first1=Sara |last2=Tack |first2=Nils |last3=Su |first3=Yunxing |last4=Cuenca-Jimenez |first4=Francisco |last5=Morales-Lopez |first5=Oscar |last6=Gomez-Valdez |first6=P. Antonio |last7=M Wilhelmus |first7=Monica |title=Pleobot: a modular robotic solution for metachronal swimming |journal=Scientific Reports |date=June 13, 2023 |volume=13 |issue=1 |page=9574 |doi=10.1038/s41598-023-36185-2 |pmid=37311777 |pmc=10264458 |bibcode=2023NatSR..13.9574O }}</ref>。 |

|||

[[ファイル:Bentheuphausia amblyops.png|thumb|right|200px|ソコオキアミ]] |

|||

[[ソコオキアミ科]] {{sname||Bentheuphausiidae}} |

|||

* ''Bentheuphausia''(一属一種) |

|||

** [[ソコオキアミ]] ''Bentheuphausia amblyops'' |

|||

== 出典 == |

== 出典 == |

||

{{Reflist|2}} |

|||

<references /> |

|||

== 参考文献 == |

== 参考文献 == |

||

| 167行目: | 208行目: | ||

{{Commonscat|Krill}} |

{{Commonscat|Krill}} |

||

{{Wikispecies|Euphausia}} |

|||

{{Taxonbar|from=Q29498}} |

|||

{{Animal-stub}} |

|||

{{Normdaten}} |

{{Normdaten}} |

||

{{DEFAULTSORT:おきあみ}} |

{{DEFAULTSORT:おきあみ}} |

||

2024年12月9日 (月) 09:33時点における最新版

| オキアミ目 | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Northern krill Meganyctiphanes norvegica

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| 分類 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| 学名 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Euphausiacea Dana, 1852 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 英名 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Krill | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 科 | |||||||||||||||||||||

オキアミ(沖醤蝦、英: krill)は、軟甲綱 真軟甲亜綱 ホンエビ上目 オキアミ目に属する甲殻類の総称。学名から Euphausiids とも呼ばれる[1]。英名の「Krill」はノルウェー語で「稚魚」を意味する[2]。世界中の海洋に生息する小型甲殻類である[3]。形態はエビに似るが、胸肢の付け根に鰓が露出している点でエビ目とは区別できる[4]。プランクトン(浮遊生物)であるが、体長3-6cmなのでプランクトンとしてはかなり大きい。

食物連鎖の底辺に近く、重要な栄養段階を占めると考えられている。植物プランクトンや動物プランクトンを食べ、多くの大型動物の主な食料源でもある。南極海におけるナンキョクオキアミの推定バイオマス量は約3億7900万トンで[5]、総バイオマス量が最も大きい種の1つとなっている。ナンキョクオキアミの半分以上は、毎年クジラ、アザラシ、ペンギン、海鳥、イカ、魚類に食べられている。ほとんどのオキアミは毎日大規模な日周鉛直移動を行い、夜間は海面近くで、日中は深海で生活する。

南極海と日本近海では商業的に漁獲されている。世界全体の漁獲量は年間15万-20万トンで、そのほとんどはスコシア海で漁獲される。漁獲されたオキアミのほとんどは養殖や水族館の餌、スポーツフィッシングの餌、または製薬において使われる。日本で販売されているのは、三陸沖などで漁獲されるツノナシオキアミ(イサダ)と、南極海に生息するナンキョクオキアミである。 後者はシロナガスクジラなどヒゲクジラ類の主要な餌料である。オキアミはいくつかの国で食用にもされている。スペインとフィリピンでは camarones として知られている。フィリピンでは alamang とも呼ばれ、バゴーンと呼ばれる塩辛いペーストを作るのに使われている。日本で「アミエビ」の名で塩辛などの食品として売られているものは本種ではなく、より小型の名称の似たエビの一種である「アキアミ」である。

分類

[編集]オキアミ目には2科が知られている。オキアミ科には10属に約85種が分類され、オキアミ属には最多の31種が属する[6]。ソコオキアミ科には水深1000m以上の深海に生息するソコオキアミ1種のみが分類され、現存するオキアミの中で最も原始的な種と考えられている[7]。ナンキョクオキアミ、ツノナシオキアミ、Northern krillなどは商業漁業の対象となる[8]。

系統

[編集]| オキアミ目の系統分類[9] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 系統分類は形態学に基づき、(♠) はMaas & Waloszek(2001)内で提唱された分類群で[9]、(♣) はネマトブラキオン属と関連する側系統群であり[9]、(♦) はCasanova (1984)とは異なり[10]、カクエリオキアミ属は Nyctiphanes の姉妹群、オキアミ属はチサノポーダ属の姉妹群、ネマトブラキオン属はスティロケイロン属の姉妹群である。 |

オキアミ目は裸出した樹枝状の鰓や細い胸脚など、いくつかの独特な固有派生形質を持つため、単系統群であると考えられており[11]、分子生物学的研究によっても同様の結果が得られている[12][13][14]。

オキアミ目の位置については多くの説がある。1830年にアンリ・ミルヌ=エドワールが初めて Thysanopode tricuspide を記載し、どちらも二枝に分かれた胸脚を持つため、当時の学者はオキアミ目とアミ目を裂脚目 Schizopoda に分類したが、1883年にヨハン・エリック・ヴェスティ・ボアズは裂脚目を2つの目に分割した[15]。1904年にウィリアム・トーマス・カルマンはアミ目をフクロエビ上目、オキアミ目をホンエビ上目に分類したが、1930年代までは裂脚目を認める意見もあった[11]。その後はロバート・ガーニーとイザベラ・ゴードンが指摘したように、発達段階の類似性に基づき、十脚目のクルマエビ科と同じグループに分類されるべきであると提案された[16][17]。オキアミは十脚目とアミ目の形態学的特徴の一部を共有しているため、こうした議論が起こったのである[11]。

分子生物学的研究では、ソコオキアミやアンフィオニデスなど重要な種が少ないためか、明確な分類が出来ていない。ある研究では基底的なアミ目を含むホンエビ上目の単系統性を支持しており[18]、別の研究ではオキアミ目をアミ目と分類し[13]、さらに別の研究ではオキアミ目をトゲエビ亜綱と分類している[19]。

進化

[編集]オキアミ目と明確に特定できる化石は現在知られていない。絶滅した真軟甲亜綱の中には、Anthracophausia、現在は奇泳目に分類されている Crangopsis [9]、Palaeomysis など、オキアミ目に分類されてきた属も存在する[20]。種分化の年代は分子時計によって推定されており、オキアミ科の最後の共通祖先は、約1億3千万年前の前期白亜紀に生息していたとされる[13]。

下位分類

[編集]主に和名のある種を挙げる。和名と種数は佐々木(2023)を参考[21]。

- オキアミ科 Euphausiidae

- オキアミ属 Euphausia - 34種

- Hansarsia - 7種

- ホソテナガオキアミ Hansarsia tenella

- Meganyctiphanes - 1種

- ネマトブラキオン属 Nematobrachion - 3種

- Nyctiphanes - 4種

- カクエリオキアミ属 Pseudeuphausia - 3種

- カクエリオキアミ Pseudeuphausia latifrons

- スティロケイロン属 Stylocheiron - 12種

- ヒゲブトテナガオキアミ Stylocheiron carinatum

- テッサラブラキオン属 Tessarabrachion - 1種

- チサノエッサ属 Thysanoessa - 10種

- ノコギリテナガオキアミ Thysanoessa gregaria

- トゲホクヨウオキアミ (シャコタンオキアミ) Thysanoessa inermis

- チサノポーダ属 Thysanopoda - 14種

- ソコオキアミ科 Bentheuphausiidae - 1属1種

- ソコオキアミ属 Bentheuphausia

分布

[編集]世界中の海域に分布し、多くの種は特定の地域の沿岸の固有種である。ソコオキアミは世界中の深海に分布する汎存種である[22]。チサノエッサ属は大西洋と太平洋に分布する[23]。ツノナシオキアミは太平洋に分布する。Northern krillは地中海から大西洋にかけて分布する。Nyctiphanes 属の4種は沿岸域に分布する[24]。カリフォルニア海流、フンボルト海流、ベンゲラ海流、カナリア海流の湧昇域に非常に豊富である[25][26][27]。コオリオキアミは南極大陸の沿岸に固有である[28]。その他にも Nyctiphanes capensis はベンゲラ海流に[24]、Euphausia mucronata はフンボルト海流に[29]、オキアミ属の6種は南極海に固有である。

南極からは7種が知られており[30]、チサノエッサ属の Thysanoessa macrura、オキアミ属の6種が知られる。ナンキョクオキアミは一般に水深100mに生息し[31]、コオリオキアミは通常水深300-600m、最大4,000mに生息する[32]。大群で日周鉛直移動を行い、音響測定によると水深400mまで移動することが分かっている[33]。ナンキョクオキアミとコオリオキアミはともに南緯55度線以南に分布し、コオリオキアミは南緯74度線以南で優占しており[34]、流氷域にも分布する。その他にも Euphausia frigida、Euphausia longirostris、Euphausia triacantha、Euphausia vallentini などの種が南極海に分布する[35]。

形態

[編集]

他の甲殻類と同様に、キチン質から成る外骨格を持つ。外見的には遊泳生のエビ類によく似ており、頭胸部は背甲に覆われ、腹部は6節からなる腹節と尾節からなる。腹部には10本の遊泳脚と尾扇がある。胸部には8節があり、それぞれに附属肢があるが、エビを含む十脚類ではその前3対が顎脚となっているのに対して、オキアミ類ではそのような変形が見られない。第2,第3節が鋏脚として発達する例や、最後の1-2対が退化する例もある。それらの胸部附属肢の基部の節には外に向けて発達した樹枝状の鰓がある。これが背甲に覆われないのもエビ類との違いである。よく似たアミ目とは胸脚の基部に鰓がないこと、尾肢に平衡胞がある点などで区別される。分類上はアミ目はフクロエビ上目とされ、系統的にもやや遠いと考えられている。2本の触角と、数対の胸脚を持つ。胸脚の数は属や種によって異なる。胸脚には摂食の為の脚と、体の手入れのための脚が含まれる。十脚目と共通して遊泳脚を持っており、これはロブスターやザリガニのものと類似している。このためオキアミは十脚目の姉妹群と考えられることがある。

外殻はほとんどの種で透明である。複雑な複眼を持ち、一部の種は色素を遮蔽することでさまざまな照度に適応している[36]。ほとんどのオキアミは成体でも約1-2cmで、いくつかの種は6-15cmに成長する。最大種である Thysanopoda cornuta は外洋の深海に生息する[37]。外部から見える鰓によって、他の甲殻類と簡単に区別できる[38]。

ソコオキアミは発光しないが、オキアミ科は発光器を持ち、生物発光を行う。ルシフェリンがルシフェラーゼによって活性化され、酵素を触媒とした化学発光が起こる。研究によると多くのオキアミのルシフェリンは、渦鞭毛藻のルシフェリンに似ているが異なる蛍光テトラピロールであり[39]、オキアミはおそらくこの物質を渦鞭毛藻を含む食事から獲得している[40]。オキアミの発光器はレンズと焦点を合わせる能力を備えた複雑な器官であり、筋肉によって回転させることができる[41]。これらの器官の正確な機能は未だ不明だが、繁殖など他個体との相互作用、方向感覚の調節、カウンターシェーディングなどの機能が考えられる[42][43]。

生態系内の役割

[編集]生物ポンプ

[編集]

オキアミは生物ポンプによる海洋隔離の一端を担っており、まず植物プランクトンが大気から海洋表層に溶解した二酸化炭素(90 Gt yr−1)を一時生産の過程で粒子状有機炭素(~ 50 Gt C yr−1)に変換する。その後植物プランクトンはオキアミや動物プランクトンに消費され、それらもさらに高次の捕食者によって消費される。残った植物プランクトンは凝集体を形成し、動物プランクトンの糞とともに急速に沈み、混合層から排出される(< 12 Gt C yr−1 14)。オキアミ、動物プランクトン、微生物は表層の植物プランクトンや深層の堆積粒子を消費し、呼吸によって有機炭素を溶存無機炭素である二酸化炭素に変換するため、表層で生成された炭素のうち、1000m以上の深海へ沈むものはごくわずかである。オキアミや小型の動物プランクトンは摂餌や排泄によって粒子を小さく断片化し、粒子状有機炭素の排出を遅らせる。これにより溶存有機炭素が細胞から直接、またはバクテリアの可溶化を介して間接的に放出される。その後細菌は溶存有機炭素を溶存無機炭素に再ミネラル化する。日周鉛直移動をするオキアミ、小型動物プランクトン、魚類は夜間に表層の溶存有機炭素を消費し、昼間に中深層で代謝することで、炭素を深層まで能動的に輸送する。能動輸送は生物の生態に応じて季節的に発生する可能性もある[44]。

食性

[編集]多くのオキアミは濾過摂食を行う[26]。胸脚には細かい櫛があり、水を吸い込んで餌を濾過することができる。植物プランクトン、特に珪藻を餌とする種では非常に細かい。ほとんどが雑食性であるが[45]、少数の種は肉食性で、動物プランクトンや仔魚を捕食する[46]。食物連鎖の重要な要素であり、一次生産者である微細藻類を大型動物が食べられる形に変換している。Northern krillや他のいくつかの種は濾過器が比較的小さく、カイアシ類や大型の動物プランクトンを積極的に捕食する[46]。直径5mm以下のマイクロプラスチックを消化し、分解して環境中に排出することができる[47]。

天敵

[編集]魚やペンギンのような小型動物からアザラシやヒゲクジラのような大型動物まで、多くの動物がオキアミを捕食する[48]。生態系の撹乱によりオキアミの個体数が減少すると、広範囲に影響を及ぼす可能性がある。例えば1998年にベーリング海で円石藻が大量発生した際[49]、珪藻の濃度が低下した。オキアミは小さな円石藻を食べることができないため、特にツノナシオキアミの個体数が急激に減少した。これにより他の種にも影響を及ぼし、ミズナギドリの個体数が減少した。オキアミの減少はそのシーズンにサケが産卵しなかった理由の1つであると考えられている[50]。

寄生性の繊毛虫である Collinia 属はオキアミに感染し、感染した個体群を壊滅させる可能性がある。感染はベーリング海のトゲホクヨウオキアミや、北米太平洋岸沖のツノナシオキアミ、Thysanoessa spinifera、ノコギリテナガオキアミから報告されている[51][52]。アミヤドリムシ科に寄生されることもある。Oculophryxus bicaulis は Stylocheiron affine や Stylocheiron longicorne の眼柄に付着し、頭部から血を吸うことが判明している。寄生されたオキアミは成熟しなかったことから、宿主の繁殖を阻害していると考えられる[53]。気候変動もオキアミの個体群にとって脅威となっている[54]。

生態と行動

[編集]

オキアミの生態は種によって若干の違いはあるものの、比較的よく理解されている[16][26]。孵化した幼生は三対の附属肢を持つノープリウスであり、その後ほぼ体全体が背甲に覆われるメタノープリウス期、腹部が伸長したカリプトピス期、複眼が柄を持って突き出すフルシリア期を経て、附属肢が発達した成体となる。生息域によっても異なるが、成熟までに1-3年を要すると考えられている。卵嚢内に卵を産む種では、ノープリウスとメタノープリウスの間にpseudometanaupliusという独自の期間がある。成長と脱皮を繰り返し、小型個体は脱皮の頻度が高い。体内に蓄えられた卵黄により、メタノープリウス幼生は栄養を得る。

カリプトピス期までに細胞分化が進み、口と消化管が発達し、植物プランクトンを食べ始める。その頃には卵黄が尽き、藻類の多い海洋表層に到達する。フルシリア期には最前部の節から遊泳脚を持つ節が生まれる。新しい遊泳脚は、次の脱皮時にのみ機能する。フルシリア期に追加される節の数は、環境条件に応じて同種であっても異なる場合がある[55]。フルシリア期を経て成体と同様の形となり、生殖腺が発達して性成熟する[56]。高緯度に生息するナンキョクオキアミのように6年以上生きるものもあれば、中緯度に生息するツノナシオキアミのように2年しか生きない種もある[8]。低緯度に生息する種の寿命はさらに短く、Nyctiphanes simplex の寿命は通常6-8ヶ月である[57]。

繁殖

[編集]

繁殖期は種や気候によって異なり、一般に雄は雌の第6胸脚の基部にある生殖孔に精莢を産み付ける。侵入した精子は一時的に貯精嚢に蓄えられる。雌は卵巣に数千個の卵子を持ち、その量は体重の3分の1にもなる[58]。1回の繁殖期の間に複数回の繁殖を行うこともあり、その間隔は数日程度である[27][59]。

2種類の産卵方法が知られている[27]。ソコオキアミ、オキアミ属、Meganyctiphanes 属、チサノエッサ属、チサノポーダ属の57種は「broadcast spawners (放出産卵)」であり、雌が受精卵を水中に放出し、卵は通常沈んで分散する。これらの種は通常ノープリウス期で孵化するが、メタノープリウス期やカリプトピス期で孵化する例も発見されている[60]。残りの29種は「sac spawners (嚢産卵)」であり、雌が卵を胸脚の一部が広がった抱卵肢に付着させてメタノープリウス期に孵化するまで運ぶが、Hansarsia difficilis などの一部の種はノープリウス期またはpseudometanauplius期に孵化することもある[61]。

脱皮

[編集]外骨格よりも大きく成長し、窮屈になると脱皮する。若い個体は成長が早く、大型個体よりも頻繁に脱皮する。脱皮の頻度は種によって大きく異なり、同じ種の中でも緯度、水温、餌の入手可能性など多くの外的要因の影響を受ける。亜熱帯の種である Nyctiphanes simplex は、脱皮間隔が2-7日である。幼生は平均4日ごとに脱皮し、幼体と成体は平均6日ごとに脱皮する。南極海に生息するナンキョクオキアミでは、脱皮間隔は-1から4℃の水温に応じて9-28日であることが観察されており、北海に生息する Meganyctiphanes norvegica でも脱皮間隔は9-28日であるが、水温は2.5-15℃である[62]。ナンキョクオキアミは餌が足りないときには体の大きさを小さくすることができ、外骨格が大きくなりすぎると脱皮する[63]。同様の能力は、極地から温帯にかけての太平洋に生息するツノナシオキアミでも、高水温への適応として観察されている。他の温帯のオキアミにも同様の能力があると予測されている[64]。

群れ

[編集]

ほとんどのオキアミは群れを作るが、その大きさと密度は種と地域によって異なる。ナンキョクオキアミの場合、群れの密度は1m3あたり10,000-60,000匹に達する[65][66]。群れを作ることは防御になり、小型の捕食者を混乱させる。2012年に発表された研究では、オキアミの群れの行動がモデル化され。他の個体の存在によって引き起こされる動き、摂餌、ランダムな移動が考慮された[67]。群れが密集すると、特に水面近くでは魚、鳥、哺乳類の捕食者の間で餌を巡る激しい争いを引き起こす可能性がある。群れは襲撃されると散り散りになり、中には瞬時に脱皮し、殻を囮にする個体も観察されている[68]。

移動

[編集]

日中は深海で過ごし、夜間に水面に浮上する日周鉛直移動を行う。深く潜るほど活動は鈍くなるが[69]、捕食者との遭遇を減らし、エネルギーを節約することができる。オキアミの遊泳活動は胃の満腹度によって変化する。水面で餌を食べた満腹のオキアミは泳ぎが鈍くなり、混合層の下に沈んでいく[70]。沈む際には排泄物を出すため、これが南極の炭素循環に関与している。胃が空のオキアミはより活発に泳ぐため、水面に向かう。垂直移動は1日に2-3回起こることがある。ナンキョクオキアミ、ツノナシオキアミ、Euphausia hanseni、カクエリオキアミ、Thysanoessa spinifera など一部の種は、捕食される危険が高いにもかかわらず、摂餌と繁殖の目的で日中に水面に群れを形成する[71]。アルテミアをモデルにした実験では、オキアミが集団で垂直移動することにより下向きの水流を作り出し、海洋の混合に大きな影響を与える可能性があることが示された[72]。

毎秒5-10cmの速度で泳ぎ[73]、推進力として遊泳脚を使用する。より長い距離を移動すると海流の影響を受ける。脅威を感じると尾を振り回して比較的素早く水中を後進し、遊泳の10-27倍の速度に達する。ナンキョクオキアミのような大型種の場合、約0.8m/sに相当する[74]。オキアミの遊泳能力から、多くの研究者は成体のオキアミを弱い流れに逆らって移動するネクトンに分類している。幼生は一般にプランクトンとされる[75]。

海洋循環における影響

[編集]ナンキョクオキアミは生物地球化学的循環と[44][76]と南極の食物連鎖[77][78]において重要な種で、栄養素を循環させ、ペンギンやヒゲクジラ、シロナガスクジラに餌を供給する。

生物地球科学的循環における役割

[編集]

オキアミは表層で植物プランクトンを食べ(図の①)、その一部が植物分解物の集合体として沈む(図の②)。これは簡単に分解されるため、水温躍層よりも下に沈まない可能性がある。オキアミは糞も放出し(図の③)、これは深海に沈むこともあるが、通常は沈む途中でオキアミ、バクテリア、動物プランクトンによって消費され、分解される(図の④)。氷縁域では糞がより深いところまで達することがある(図の⑤)。オキアミの脱皮殻は沈んで炭素フラックスに寄与する(図の⑥)。鉄やアンモニウムなどの栄養素は、オキアミの摂餌や排泄に伴って放出される(図の⑦)。これが表層近くで放出されると、植物プランクトンの生成を刺激し、大気中の二酸化炭素のさらなる減少につながる可能性がある。成体のオキアミの中には、より深いところに生息し、深海にある有機物を食べるものもいる(図の⑧)。水温躍層の下に有機物または二酸化炭素の形で沈んだ炭素は、季節的な混合の影響を受けなくなり、少なくとも1年間は深海に貯蔵される(図の⑨)。成体のオキアミの回遊により、深海の栄養豊富な水が混合され(図の⑩)、一次生産がさらに刺激される。また成体のオキアミは海底で餌を探し、呼吸によって二酸化炭素を深海に放出し、底生捕食者に消費される可能性がある(図の⑪)。南極海の海氷の下に生息する幼生は、広範囲にわたる日中鉛直移動を行い(図の⑫)、水温躍層の下に二酸化炭素を移動させる可能性がある。ヒゲクジラを含む多くの捕食者に消費されるため(図の⑬)、オキアミの炭素の一部はクジラが死んで海底に沈み、深海生物に消費されるまでの数十年間、バイオマスとして貯蔵される[44]。

個体レベルの栄養素の循環

[編集]

オキアミは脱皮時に、溶解したカルシウム、フッ化物、リンを外骨格から放出する(図の①)。外骨格を形成するキチンは有機物であり、深海の沈降粒子フラックスに寄与する。オキアミは植物プランクトンや他の動物を消費して得たエネルギーの一部を呼吸によって二酸化炭素に変換する(図の②)。中深層から大群で水面まで泳ぐとき(図の③)、栄養分の少ない表層水に栄養をもたらす可能性があり、アンモニウムとリン酸が鰓から放出され、排泄の際には溶解した有機炭素、窒素、尿素、リン(DOC、DON、DOP)が放出される(図の②および④)。粒子状の有機炭素、窒素、リン(POC、PON、POP)と鉄を含む沈みやすい糞を放出する。鉄はDOC、DON、DOP とともに周囲の水に浸出すると生体利用が可能になる(図の⑤)[44]。

人との関わり

[編集]漁業の歴史

[編集]

オキアミは少なくとも19世紀から人間や家畜の食料として採取されてきたが、日本ではおそらくそれ以前から知られていた。大規模な漁業は1960年代後半から1970年代前半にかけて発展し、現在は南極海と日本近海でのみ行われている。歴史的にオキアミ漁業が盛んな国は日本とソ連、ソ連崩壊後はロシアとウクライナであった[79]。漁獲量がピークを迎えた1983年には南極海だけで約52万8千トン(うちソ連が93%を漁獲)が漁獲され、現在は乱獲防止のために管理されている[80]。1993年、ロシアがオキアミ漁業から撤退したことと、南極の海洋生物資源の保存に関する委員会がナンキョクオキアミの持続可能な利用のために最大漁獲量を定めたことにより、オキアミ漁業は衰退した。2011年10月の見直しの後、委員会は漁獲量を変更しないことを決定した[81]。南極での年間漁獲量は10万トン前後で安定しており、これは委員会の漁獲割当量のおよそ50分の1に相当する[82]。おそらくコストの高さと政治的および法的問題により、漁獲量は制限されている[83]。日本の漁業は約7万トンで飽和状態になった[84]。オキアミは世界中に生息しているが、南極海では個体数が豊富で漁獲しやすいため、操業が好まれている。南極海のオキアミは「クリーンな製品」とみなされている[79]。2018年には、南極で操業しているほぼ全てのオキアミ漁会社が、ペンギンの繁殖コロニー周辺を含む南極半島周辺の広大な海域での操業を2020年から中止すると発表した[85]。

消費

[編集]

ナンキョクオキアミの総バイオマス量は4億トンにも達するが、このキーストーン種に対する人間の影響は増大しており、2010年から2014年にかけて総漁獲量は39%増加して294,000トンとなった。オキアミの漁獲を行う主な国は、ノルウェー(2014年の総漁獲量の56%)、韓国(19%)、中国(18%)である[82]。

漁獲されたオキアミは未加工もしくはフリーズドライ加工され、または粉末状で販売され、養殖漁業の飼料用、釣り餌、観賞魚の餌などに利用される。飼料としてのオキアミには、魚の耐病性向上や、観賞魚の体色の発色向上などの効果があって人気が高い。日本ではナンキョクオキアミの34%、ツノナシオキアミの50%が魚の飼料として消費される。また日本では70年代に海釣りの撒きえさとして導入され、黒鯛やメジナ、またサビキ釣りのテクニックに革命を起こした。ナンキョクオキアミの4分の1、ツノナシオキアミの半分は釣りえさ用である。オキアミはタンパク質とω-3脂肪酸を豊富に含んでおり、21世紀初頭からは人間の食料、オイルカプセルなどのサプリメント、家畜の餌、ペットフードとして開発が進められている[79][81][86]。

魚肉ソーセージなど加工食品の原料にもなり[87]、また調味料として塩辛も作られている。これは朝鮮半島や日本でキムチの発酵にアキアミの塩辛同様に使われる事がある[88]。以前は漁獲後の劣化が早く風味落ちがするため、人間の食用としての消費はきわめて少なかったが、近年加工技術の進化により、ツノナシオキアミはサクラエビの安価な代用品としてお好み焼きなどに利用されている。オキアミは塩辛く、エビよりも魚の風味がやや強い。市販の製品として大量に消費するためには、食べられない殻を剥く必要がある[86]。釣りえさ用として販売されているオキアミの食用は、控えるべきである。原料鮮度や製造過程の衛生管理が食品加工法規の適用外であり、また食品に適さない薬品が添加されている可能性もあるからである。

DHA・EPA・アスタキサンチンの摂取を目的に南極オキアミから採取した油脂クリルオイルを原料として製造される健康食品もある。2011年、アメリカ食品医薬品局は、製造されたクリルオイル製品が人間の消費に安全であると発表した[89]。

オキアミを含む小型甲殻類は東南アジアで最も広く消費されており、殻付きのまま発酵させ、細かく挽いてシュリンプペーストを作ることが多い。炒めて白米と一緒に食べたり、様々な伝統料理にうま味を加えるために使用したりする[90][91]。発酵過程で得られる液体は魚醤としても使用される[92]。カップヌードルの具材に使われるエビがオキアミであるとされることがあるが、使用されているのはプーバランである。

食料以外での利用

[編集]オキアミは中程度のレイノルズ数の領域で機敏に泳ぐが、この領域では無人水中ロボットの移動が難しく、オキアミの移動を研究することで、水中ロボットの設計に応用する試みが進められている[93]。

出典

[編集]- ^ “Euphausiids (Krill)”. Government of Canada. Fisheries and Oceans Canada (2022年4月6日). 2024年12月7日閲覧。 “Many different species of euphausiids are found on Canada's east and west coasts.”

- ^ "Krill". Online Etymology Dictionary. 2024年12月7日閲覧。

- ^ Lindley, Alistair J. (2017-10-19) (英語). Crustacea: Euphausiacea. 1. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780199233267.003.0030

- ^ 大塚攻・駒井智幸 「3.甲殻亜門」 『節足動物の多様性と系統』 石川良輔編、岩槻邦男・馬渡峻輔監修、裳華房、2008年、172-268頁

- ^ A. Atkinson; V. Siegel; E.A. Pakhomov; M.J. Jessopp; V. Loeb (2009). “A re-appraisal of the total biomass and annual production of Antarctic krill”. Deep-Sea Research Part I 56 (5): 727–740. Bibcode: 2009DSRI...56..727A. doi:10.1016/j.dsr.2008.12.007.

- ^ Siegel V (2024). Siegel V (ed.). "Euphausiidae Dana, 1852". World Euphausiacea database. World Register of Marine Species. 2024年12月7日閲覧。

- ^ E. Brinton (1962). “The distribution of Pacific euphausiids”. Bull. Scripps Inst. Oceanogr. 8 (2): 51–270.

- ^ a b S. Nicol; Y. Endo (1999). “Krill fisheries: Development, management and ecosystem implications”. Aquatic Living Resources 12 (2): 105–120. doi:10.1016/S0990-7440(99)80020-5.

- ^ a b c d Andreas Maas; Dieter Waloszek (2001). “Larval development of Euphausia superba Dana, 1852 and a phylogenetic analysis of the Euphausiacea”. Hydrobiologia 448: 143–169. doi:10.1023/A:1017549321961. オリジナルの18 July 2011時点におけるアーカイブ。.

- ^ Bernadette Casanova (1984). “Phylogénie des Euphausiacés (Crustacés Eucarides) [Phylogeny of the Euphausiacea (Crustacea: Eucarida)]” (フランス語). Bulletin du Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle 4: 1077–1089.

- ^ a b c Bernadette Casanova (2003). “Ordre des Euphausiacea Dana, 1852”. Crustaceana 76 (9): 1083–1121. doi:10.1163/156854003322753439. JSTOR 20105650.

- ^ M. Eugenia D'Amato; Gordon W. Harkins; Tulio de Oliveira; Peter R. Teske; Mark J. Gibbons (2008). “Molecular dating and biogeography of the neritic krill Nyctiphanes”. Marine Biology 155 (2): 243–247. doi:10.1007/s00227-008-1005-0. オリジナルの2012-03-17時点におけるアーカイブ。 2010年7月4日閲覧。.

- ^ a b c Simon N. Jarman (2001). “The evolutionary history of krill inferred from nuclear large subunit rDNA sequence analysis”. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 73 (2): 199–212. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2001.tb01357.x.

- ^ Xin Shen; Haiqing Wang; Minxiao Wang; Bin Liu (2011). “The complete mitochondrial genome sequence of Euphausia pacifica (Malacostraca: Euphausiacea) reveals a novel gene order and unusual tandem repeats”. Genome 54 (11): 911–922. doi:10.1139/g11-053. PMID 22017501.

- ^ Johan Erik Vesti Boas (1883). “Studien über die Verwandtschaftsbeziehungen der Malacostraken [Studies on the relationships of the Malacostraca]” (ドイツ語). Morphologisches Jahrbuch 8: 485–579.

- ^ a b Robert Gurney (1942). Larvae of Decapod Crustacea. Ray Society

- ^ Isabella Gordon (1955). “Systematic position of the Euphausiacea”. Nature 176 (4489): 934. Bibcode: 1955Natur.176..934G. doi:10.1038/176934a0.

- ^ Trisha Spears, Ronald W. DeBry, Lawrence G. Abele & Katarzyna Chodyl (2005). Boyko, Christopher B.. ed. “Peracarid monophyly and interordinal phylogeny inferred from nuclear small-subunit ribosomal DNA sequences (Crustacea: Malacostraca: Peracarida)”. Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington 118 (1): 117–157. doi:10.2988/0006-324X(2005)118[117:PMAIPI]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ K. Meland; E. Willassen (2007). “The disunity of "Mysidacea" (Crustacea)”. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 44 (3): 1083–1104. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2007.02.009. PMID 17398121.

- ^ Frederick R. Schram (1986). Crustacea. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-503742-5

- ^ 佐々木潤 (2023) 世界大型甲殻類目録 The Species List of Decapoda,Euphausiacea, and Stomatopoda,all of the World. Version. 07-8.12 2024年12月6日閲覧。

- ^ J. J. Torres; J. J. Childress (1985). “Respiration and chemical composition of the bathypelagic euphausiid Bentheuphausia amblyops”. Marine Biology 87 (3): 267–272. doi:10.1007/BF00397804.

- ^ Volker Siegel (2024). "Thysanoessa Brandt, 1851". World Register of Marine Species. 2024年12月7日閲覧。

- ^ a b D’Amato, M. Eugenia; Harkins, Gordon W.; de Oliveira, Tulio; Teske, Peter R.; Gibbons, Mark J. (2008-08). “Molecular dating and biogeography of the neritic krill Nyctiphanes” (英語). Marine Biology 155 (2): 243–247. doi:10.1007/s00227-008-1005-0. ISSN 0025-3162.

- ^ Volker Siegel (2024年). V. Siegel: “Nyctiphanes Sars, 1883”. World Euphausiacea database. World Register of Marine Species. 2024年12月7日閲覧。

- ^ a b c J. Mauchline、L. R. Fisher『The Biology of Euphausiids』 7巻、Academic Press〈Advances in Marine Biology〉、1969年。ISBN 978-7-7708-3615-2。

- ^ a b c Jaime Gómez-Gutiérrez; Carlos J. Robinson (2005). “Embryonic, early larval development time, hatching mechanism and interbrood period of the sac-spawning euphausiid Nyctiphanes simplex Hansen”. Journal of Plankton Research 27 (3): 279–295. doi:10.1093/plankt/fbi003.

- ^ S. N. Jarman; N. G. Elliott; S. Nicol; A. McMinn (2002). “Genetic differentiation in the Antarctic coastal krill Euphausia crystallorophias”. Heredity 88 (4): 280–287. doi:10.1038/sj.hdy.6800041. PMID 11920136.

- ^ R. Escribano; V. Marin; C. Irribarren (2000). “Distribution of Euphausia mucronata at the upwelling area of Peninsula Mejillones, northern Chile: the influence of the oxygen minimum layer”. Scientia Marina 64 (1): 69–77. doi:10.3989/scimar.2000.64n169.

- ^ P. Brueggeman. “Euphausia crystallorophias”. Underwater Field Guide to Ross Island & McMurdo Sound, Antarctica. University of California, San Diego. 2008年5月11日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年5月11日閲覧。

- ^ “Krill, Euphausia superba”. MarineBio.org. 2024年12月7日閲覧。

- ^ J. A. Kirkwood (1984). “A Guide to the Euphausiacea of the Southern Ocean”. ANARE Research Notes 1: 1–45.

- ^ Bianchi, Daniele; Mislan, K.A.S. (January 2016). “Global patterns of diel vertical migration times and velocities from acoustic data”. Limnology and Oceanography 61 (1). doi:10.1002/lno.10219.

- ^ A. Sala; M. Azzali; A. Russo (2002). “Krill of the Ross Sea: distribution, abundance and demography of Euphausia superba and Euphausia crystallorophias during the Italian Antarctic Expedition (January–February 2000)”. Scientia Marina 66 (2): 123–133. doi:10.3989/scimar.2002.66n2123.

- ^ Hosie, G.W; Fukuchi, M; Kawaguchi, S (2003-08). “Development of the Southern Ocean Continuous Plankton Recorder survey” (英語). Progress in Oceanography 58 (2-4): 263–283. doi:10.1016/j.pocean.2003.08.007.

- ^ E. Gaten. “Meganyctiphanes norvegica”. University of Leicester. 2009年7月1日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2009年2月25日閲覧。

- ^ E. Brinton (1953). “Thysanopoda spinicauda, a new bathypelagic giant euphausiid crustacean, with comparative notes on T. cornuta and T. egregia”. Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences 43: 408–412.

- ^ “Euphausiacea”. Tasmanian Aquaculture & Fisheries Institute. 2009年9月30日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2010年6月6日閲覧。

- ^ O. Shimomura (1995). “The roles of the two highly unstable components F and P involved in the bioluminescence of euphausiid shrimps”. Journal of Bioluminescence and Chemiluminescence 10 (2): 91–101. doi:10.1002/bio.1170100205. PMID 7676855.

- ^ J. C. Dunlap; J. W. Hastings; O. Shimomura (1980). “Crossreactivity between the light-emitting systems of distantly related organisms: novel type of light-emitting compound”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 77 (3): 1394–1397. Bibcode: 1980PNAS...77.1394D. doi:10.1073/pnas.77.3.1394. JSTOR 8463. PMC 348501. PMID 16592787.

- ^ P. J. Herring; E. A. Widder (2001). “Bioluminescence in Plankton and Nekton”. In J. H. Steele; S. A. Thorpe; K. K. Turekian. Encyclopedia of Ocean Science. 1. Academic Press, San Diego. pp. 308–317. ISBN 978-0-12-227430-5

- ^ S. M. Lindsay; M. I. Latz (1999). Experimental evidence for luminescent countershading by some euphausiid crustaceans. American Society of Limnology and Oceanography (ASLO) Aquatic Sciences Meeting. Santa Fe.

- ^ Sönke Johnsen (2005). “The Red and the Black: bioluminescence and the color of animals in the deep sea”. Integrative and Comparative Biology 4 (2): 234–246. doi:10.1093/icb/45.2.234. PMID 21676767. オリジナルの2005-10-02時点におけるアーカイブ。.

- ^ a b c d e Cavan, E.L., Belcher, A., Atkinson, A., Hill, S.L., Kawaguchi, S., McCormack, S., Meyer, B., Nicol, S., Ratnarajah, L., Schmidt, K. and Steinberg, D.K. (2019) "The importance of Antarctic krill in biogeochemical cycles". Nature communications, 10(1): 1–13. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-12668-7.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.