前骨髄球性白血病タンパク質

前骨髄球性白血病タンパク質(ぜんこつずいきゅうせいはっけつびょうタンパクしつ、英: promyelocytic leukemia protein、略称: PML)は、PML遺伝子のタンパク質産物であり、 MYL、RNF71、PP8675、TRIM19[5]の名称でも知られる。PMLタンパク質はがん抑制タンパク質であり、PMLボディ(PML体)と呼ばれる核内構造体の組み立てに必要とされる。PMLボディは細胞核のクロマチン間に形成される。これらの構造体は哺乳類の核に存在し、1つの核には1から30個程度存在する[5]。PMLボディは多くの細胞調節機能を持っており、プログラム細胞死、ゲノム安定性、抗ウイルス機能、細胞分裂の制御などに関与している[5][6]。PMLの変異や欠失、それに伴うこれらの過程の調節異常は、多くの種類のがんと関係している[5]。

歴史

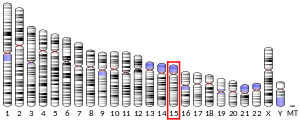

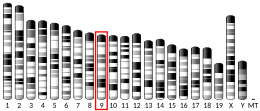

[編集]急性前骨髄球性白血病(APL)の患者を対象としたGrignaniらによる1996年の研究での知見まで、PMLの機能はあまり理解されていなかった。この研究においてAPLの患者の90%の核型で相互転座が起きており、17番染色体のレチノイン酸受容体(RARα)遺伝子と15番染色体のPML遺伝子が融合していることが初めて明らかにされた。その結果生じたPML/RARα融合遺伝子は正常なPMLとRARαの機能を妨げ、血液の前駆細胞の最終分化を阻害して、がんの進行のための未分化細胞の蓄えが維持されるようになることが示された[7]。この病理学的文脈への示唆によって、PML遺伝子は大きく注目されることとなった。

構造

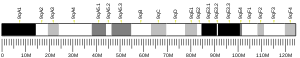

[編集]PML遺伝子はおよそ53kbの長さで、15番染色体の長腕(q)上に位置している。10個のエクソンから構成され、選択的スプライシングによって15種類以上のアイソフォームが生じることが知られている[8][9]。アイソフォーム間ではC末端ドメインに差異が存在する一方、遺伝子の最初の3つのエクソンによってコードされているtripartiteモチーフはすべてのアイソフォームに共通している[10]。tripartiteモチーフは、亜鉛結合性のRINGフィンガードメイン、B1、B2ボックスと名付けられた2つの亜鉛結合ドメイン、そしてRBCC二量体化ドメインと呼ばれる2本のαヘリックスからなるコイルドコイルドメインを含んでいる[9]。

PML遺伝子は、転写、翻訳、翻訳後の段階で制御されている。遺伝子のプロモーター領域は、STAT、インターフェロン調節因子、p53の標的配列を含んでおり、細胞機能への関与の複雑さが示唆される[11]。選択的スプライシングによる調節に加え、タンパク質産物はアセチル化やリン酸化といった翻訳後修飾を受ける。C末端はカゼインキナーゼによってリン酸化されるセリン残基を含んでおり、他にもリン酸化の標的となるチロシン残基やスレオニン残基がいくつか存在する[9]。PMLのリン酸化は、SUMO結合酵素(SUMO-conjugating enzyme)UBC9によるRINGドメインへのSUMOタンパク質の付加を引き起こす[5]。このSUMO化は細胞周期依存的に行われる。PMLは自身や他のSUMO化タンパク質との相互作用に必要なSUMO結合ドメインを含んでいる[9]。PMLのユビキチン化とSUMO化の双方がプロテアソームによる分解を誘導し、PMLの細胞内における不安定性の調節の手段として用いられている[11]。

PMLは細胞質で翻訳されるが、N末端に核局在化配列が存在するため核内へ輸送される[9]。核内では、SUMO化されたPMLはRBCCドメインどうしの相互作用によって多量体化する。これによって核マトリックスに結合するリング状の構造が形成され、PMLボディが形成される。リング状のタンパク質多量体の端からはタンパク質の糸がリングから伸びてクロマチン繊維と接触しており[5]、PMLボディの核内での位置とタンパク質の安定性が維持されている。アポトーシス時のようにクロマチンがストレスを受けると、PMLボディは不安定となり微小な構造へと再配置される。これらの微小構造はPMLタンパク質を含んでいるが、通常PMLボディに結合している相互作用タンパク質の多くは含まれていない[5][12]。

PMLボディは核内でランダムに分布しているのではなく、他の核内構造体であるスプライシングスペックルや核小体、または遺伝子に富み転写が活発に行われている領域と結合しているのが一般的である。特に、PMLボディはMHCクラスI遺伝子クラスターやp53などの遺伝子と結合することが示されている。この結合の正確な意義は不明であるが、PMLボディが特定の遺伝子部位の転写に影響を与えている可能性が示唆されている[13]。

機能

[編集]PMLボディはさまざまな機能を持っており、細胞の調節機能に大きな役割を果たす。PMLボディはそこに局在するさまざまなタンパク質との相互作用を通じて広範囲の機能を果たす。PMLボディで行われる特異的な生化学的機能は、他のタンパク質のSUMO化のためのE3リガーゼとしての機能であると考えられている[5]。しかしながら実際の機能はいまだ不明であり、PMLボディの機能については、核内のタンパク質の貯蔵、タンパク質が蓄積して翻訳後修飾が行われる場、転写への直接的な関与、クロマチンの調節など、いくつかのモデルが提唱されている[5]。

PMLボディによる転写調節機能としては、PMLボディはいくつかの遺伝子の転写を増加させ、一方で他の遺伝子については転写を抑制することが示されている[5]。PMLボディはクロマチンのリモデリングの過程を通じてこれらの機能を果たしていることが示唆されているが、不確実である[5]。PMLボディが核内における位置や、核内の特定の領域で相互作用するタンパク質、またはPMLボディに含まれるアイソフォームによって機能が異なる構造体である可能性もある。

この転写調節に加えて、タンパク質複合体がDNA損傷反応を媒介することがPMLボディの観察から強く示唆されている。例えば、PMLボディの数とサイズはDNA損傷を感知するATMやATRの活性の増加とともに増加する。この核内構造体はDNA損傷部位に局在し、そこにはその後DNA修復や細胞周期チェックポイントに関係するタンパク質が共局在する[5][13]。PMLボディがDNA修復機構と相互作用する目的はいまだ不明であるが、DNA修復タンパク質とPMLボディの共局在はDNAが損傷してからしばらく経ってからであるため、PMLボディがDNAの修復に直接関与しているとは考えにくい。むしろ、PMLボディはDNA修復に関与するタンパク質の貯蔵部位としての機能、直接的な修復の調節、またはDNA修復とチェックポイント反応との媒介によって、DNA損傷への反応を調節している可能性がある[5]。しかし、PMLボディがチェックポイント反応の媒介、特にアポトーシスの誘導において役割を果たしていることは明らかである。

PMLはp53依存的・非依存的アポトーシス経路の双方において重要な役割を果たす。PMLはp53タンパク質をPMLボディに呼び寄せて活性化を促進するとともに、MDM2やHAUSP(Herpes virus associated ubiquitin-specific protease)といったp53の調節因子を阻害する[5]。アポトーシスの誘導にp53を利用しない経路においては、PMLはCHK2と相互作用し、自己リン酸化による活性化を誘導する[5]。これらの2つのアポトーシス経路に加えて、Fasによって誘導されるアポトーシスもFLASH(FLICE-associated huge protein)の放出に関してPMLボディに依存している。FLASHはその後ミトコンドリアに局在し、カスパーゼ8の活性化を促進する[5]。

他の研究ではPMLボディの細胞老化(senescence)、特にその誘導への関与が示唆されている[5]。PMLボディは、細胞老化特異的ヘテロクロマチン構造(senescence-associated heterochromatin foci、SAHF)など、老化した細胞における特定のクロマチンの構造的特徴の形成に関与していることが示されており、これらは成長促進因子や遺伝子の発現を抑制すると考えられている。これらの特徴の形成はヒストンシャペロンであるHIRAとASF1によるものであり、ここでのクロマチンリモデリング活性はPMLボディによって媒介されている。HIRAはDNAとのいかなる相互作用よりも前にPMLボディに局在している[5]。

がんにおける役割

[編集]PMLの機能喪失変異、特にAPLにおけるPML遺伝子とRARα遺伝子の融合によるものは、がん抑制性のいくつかのアポトーシス経路、特に上述したp53依存的経路との関係が示唆されている[5][14]。PMLの機能喪失は、細胞の生存と増殖に有利となり、SAHFの喪失を通して細胞老化を妨げ、細胞分化をブロックする[14]。

ヒトとマウスの双方において、PMLの機能喪失によって腫瘍形成能が増大することが示されている。PMLの破壊は広範な種類のがんで生じており、より転移性の高い腫瘍となり、それに応じて予後も悪化する[14]。アポトーシスにおける重要性の他、PMLの不活性化は細胞にさらなる遺伝的損傷の蓄積させることによって、腫瘍の進行を促進する可能性があると考えられている。ゲノムの安定性に関与する多くのタンパク質が損傷部位への標的化をPMLボディに依存しており、そのためPMLの喪失は細胞内での修復効率の低下をもたらす[14]。

細胞周期における役割

[編集]PMLボディの分布と濃度は細胞周期の進行によって変化する。G0期では、SUMO化されたPMLボディはほとんど存在しないが、G1期からS期、G2期へと進行するにつれて、その数は増加する。有糸分裂中のクロマチン凝縮の際、PMLの脱SUMO化によって多くの結合タンパク質の解離が引き起こされ、PMLは自己凝集し、MAPP(mitotic accumulations of PML proteins)と名付けられたいくつかの巨大な凝集体を形成する[5]。数の変化に加え、PMLボディは周期の段階に応じて異なるタンパク質を結合しており、その構成に関しては生化学的に大きな変化が起こっている[5]。

細胞周期のS期の間、クロマチンの足場がDNA複製を通じて変化するためPMLボディはばらばらになる。PMLボディの小断片への物理的な解体はG2期においてPMLボディがより多く形成されるよう促進するが、一方でPMLの発現レベルは上昇していない[5]。この過程はPMLボディが結合している染色分体の方向性の維持、またはDNA複製フォークの完全性の監視に役立っている可能性があると考えられている[5]。

抗ウイルス機能

[編集]インターフェロンα/β、γの存在下でPMLの転写は増加する。このPMLの発現上昇に伴うPMLボディの数の増加は、PMLボディへのウイルスタンパク質の隔離をもたらすと考えられている。PMLボディに取り込まれたタンパク質はその後SUMO化され、ビリオンは恒久的に不活化される[6]。

相互作用

[編集]PMLタンパク質は以下のタンパク質と相互作用することが示されている。

- ANKRD2[15]

- CREB結合タンパク質[16][17][18]

- サイクリンT1[19]

- DAXX[20][21][22][23]

- GATA2[24]

- HDAC1[25][26]

- HDAC3[26]

- HHEX[27]

- MAPK11[28]

- MYB[29]

- Mdm2[30][31][32][33]

- 神経成長因子IB[34]

- 核内受容体コリプレッサー1[25]

- 核内受容体コリプレッサー2[25][35]

- p53[30][36][37]

- 60Sリボソームタンパク質L11[31]

- Rb[38]

- レチノイン酸受容体α[16]

- SIN3A[25]

- SKI[25]

- STAT3[39]

- 血清応答因子[17]

- SUMO1[40][41]

- Sp1[42]

- TOPBP1[43]

- チミンDNAグリコシラーゼ[44]

- ZBTB16[45]

出典

[編集]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000140464 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000036986 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ Human PubMed Reference:

- ^ Mouse PubMed Reference:

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w “Structure, dynamics and functions of promyelocytic leukaemia nuclear bodies”. Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology 8 (12): 1006–16. (December 2007). doi:10.1038/nrm2277. PMID 17928811.

- ^ a b “PML nuclear bodies: regulation, function and therapeutic perspectives” (英語). The Journal of Pathology 234 (3): 289–91. (November 2014). doi:10.1002/path.4426. PMID 25138686.

- ^ “Effects on differentiation by the promyelocytic leukemia PML/RARalpha protein depend on the fusion of the PML protein dimerization and RARalpha DNA binding domains”. The EMBO Journal 15 (18): 4949–58. (September 1996). doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb00875.x. PMC 452232. PMID 8890168.

- ^ “PML promyelocytic leukemia [Homo sapiens (human) - Gene - NCBI]”. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. 2016年12月6日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e “PML interaction with p53 and its role in apoptosis and replicative senescence”. Oncogene 20 (49): 7250–6. (2001). doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1204856. PMID 11704853.

- ^ “Promyelocytic leukemia (PML) protein plays important roles in regulating cell adhesion, morphology, proliferation and migration”. PLOS ONE 8 (3): e59477. (2013-03-21). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0059477. PMC 3605454. PMID 23555679.

- ^ a b “PML-mediated signaling and its role in cancer stem cells” (英語). Oncogene 33 (12): 1475–84. (March 2014). doi:10.1038/onc.2013.111. PMID 23563177.

- ^ “PML bodies: a meeting place for genomic loci?” (英語). Journal of Cell Science 118 (Pt 5): 847–54. (March 2005). doi:10.1242/jcs.01700. PMID 15731002.

- ^ a b “PML nuclear bodies: dynamic sensors of DNA damage and cellular stress” (英語). BioEssays 26 (9): 963–77. (September 2004). doi:10.1002/bies.20089. PMID 15351967.

- ^ a b c d “Loss of the tumor suppressor PML in human cancers of multiple histologic origins” (英語). Journal of the National Cancer Institute 96 (4): 269–79. (February 2004). doi:10.1093/jnci/djh043. PMID 14970276.

- ^ “The Ankrd2 protein, a link between the sarcomere and the nucleus in skeletal muscle”. Journal of Molecular Biology 339 (2): 313–25. (May 2004). doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2004.03.071. PMID 15136035.

- ^ a b “A RA-dependent, tumour-growth suppressive transcription complex is the target of the PML-RARalpha and T18 oncoproteins”. Nature Genetics 23 (3): 287–95. (November 1999). doi:10.1038/15463. PMID 10610177.

- ^ a b “PML-nuclear bodies are involved in cellular serum response”. Genes to Cells 8 (3): 275–86. (March 2003). doi:10.1046/j.1365-2443.2003.00632.x. PMID 12622724.

- ^ “Modulation of CREB binding protein function by the promyelocytic (PML) oncoprotein suggests a role for nuclear bodies in hormone signaling”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 96 (6): 2627–32. (March 1999). doi:10.1073/pnas.96.6.2627. PMC 15819. PMID 10077561.

- ^ “Recruitment of human cyclin T1 to nuclear bodies through direct interaction with the PML protein”. The EMBO Journal 22 (9): 2156–66. (May 2003). doi:10.1093/emboj/cdg205. PMC 156077. PMID 12727882.

- ^ “PML is critical for ND10 formation and recruits the PML-interacting protein daxx to this nuclear structure when modified by SUMO-1”. The Journal of Cell Biology 147 (2): 221–34. (October 1999). doi:10.1083/jcb.147.2.221. PMC 2174231. PMID 10525530.

- ^ “Sequestration and inhibition of Daxx-mediated transcriptional repression by PML”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 20 (5): 1784–96. (March 2000). doi:10.1128/mcb.20.5.1784-1796.2000. PMC 85360. PMID 10669754.

- ^ “Regulation of Pax3 transcriptional activity by SUMO-1-modified PML”. Oncogene 20 (1): 1–9. (January 2001). doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1204063. PMID 11244500.

- ^ “Promyelocytic leukemia protein (PML) and Daxx participate in a novel nuclear pathway for apoptosis”. The Journal of Experimental Medicine 191 (4): 631–40. (February 2000). doi:10.1084/jem.191.4.631. PMC 2195846. PMID 10684855.

- ^ “Potentiation of GATA-2 activity through interactions with the promyelocytic leukemia protein (PML) and the t(15;17)-generated PML-retinoic acid receptor alpha oncoprotein”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 20 (17): 6276–86. (September 2000). doi:10.1128/mcb.20.17.6276-6286.2000. PMC 86102. PMID 10938104.

- ^ a b c d e “Role of PML and PML-RARalpha in Mad-mediated transcriptional repression”. Molecular Cell 7 (6): 1233–43. (June 2001). doi:10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00257-x. PMID 11430826.

- ^ a b “The growth suppressor PML represses transcription by functionally and physically interacting with histone deacetylases”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 21 (7): 2259–68. (April 2001). doi:10.1128/MCB.21.7.2259-2268.2001. PMC 86860. PMID 11259576.

- ^ “The promyelocytic leukemia protein PML interacts with the proline-rich homeodomain protein PRH: a RING may link hematopoiesis and growth control”. Oncogene 18 (50): 7091–100. (November 1999). doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1203201. PMID 10597310.

- ^ “Promyelocytic leukemia is a direct inhibitor of SAPK2/p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 279 (39): 40994–1003. (September 2004). doi:10.1074/jbc.M407369200. PMID 15273249.

- ^ “c-Myb associates with PML in nuclear bodies in hematopoietic cells”. Experimental Cell Research 297 (1): 118–26. (July 2004). doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.03.014. PMID 15194430.

- ^ a b “Cellular stress and DNA damage invoke temporally distinct Mdm2, p53 and PML complexes and damage-specific nuclear relocalization”. Journal of Cell Science 116 (Pt 19): 3917–25. (October 2003). doi:10.1242/jcs.00714. PMID 12915590.

- ^ a b “PML regulates p53 stability by sequestering Mdm2 to the nucleolus”. Nature Cell Biology 6 (7): 665–72. (July 2004). doi:10.1038/ncb1147. PMID 15195100.

- ^ “MDM2 and promyelocytic leukemia antagonize each other through their direct interaction with p53”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 278 (49): 49286–92. (December 2003). doi:10.1074/jbc.M308302200. PMID 14507915.

- ^ “Physical and functional interactions between PML and MDM2”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 278 (31): 29288–97. (August 2003). doi:10.1074/jbc.M212215200. PMID 12759344.

- ^ “Promyelocytic leukemia protein PML inhibits Nur77-mediated transcription through specific functional interactions”. Oncogene 21 (24): 3925–33. (May 2002). doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1205491. PMID 12032831.

- ^ “Arsenic trioxide is a potent inhibitor of the interaction of SMRT corepressor with Its transcription factor partners, including the PML-retinoic acid receptor alpha oncoprotein found in human acute promyelocytic leukemia”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 21 (21): 7172–82. (November 2001). doi:10.1128/MCB.21.21.7172-7182.2001. PMC 99892. PMID 11585900.

- ^ “Regulation of p53 activity in nuclear bodies by a specific PML isoform”. The EMBO Journal 19 (22): 6185–95. (November 2000). doi:10.1093/emboj/19.22.6185. PMC 305840. PMID 11080164.

- ^ “The function of PML in p53-dependent apoptosis”. Nature Cell Biology 2 (10): 730–6. (October 2000). doi:10.1038/35036365. PMID 11025664.

- ^ “The promyelocytic leukemia gene product (PML) forms stable complexes with the retinoblastoma protein”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 18 (2): 1084–93. (February 1998). doi:10.1128/mcb.18.2.1084. PMC 108821. PMID 9448006.

- ^ “Opposing effects of PML and PML/RAR alpha on STAT3 activity”. Blood 101 (9): 3668–73. (May 2003). doi:10.1182/blood-2002-08-2474. PMID 12506013.

- ^ “Essential role of the 58-kDa microspherule protein in the modulation of Daxx-dependent transcriptional repression as revealed by nucleolar sequestration”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 277 (28): 25446–56. (July 2002). doi:10.1074/jbc.M200633200. PMID 11948183.

- ^ “Covalent modification of PML by the sentrin family of ubiquitin-like proteins”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 273 (6): 3117–20. (February 1998). doi:10.1074/jbc.273.6.3117. PMID 9452416.

- ^ “The promyelocytic leukemia protein interacts with Sp1 and inhibits its transactivation of the epidermal growth factor receptor promoter”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 18 (12): 7147–56. (December 1998). doi:10.1128/MCB.18.12.7147. PMC 109296. PMID 9819401.

- ^ “PML colocalizes with and stabilizes the DNA damage response protein TopBP1”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 23 (12): 4247–56. (June 2003). doi:10.1128/mcb.23.12.4247-4256.2003. PMC 156140. PMID 12773567.

- ^ “Noncovalent SUMO-1 binding activity of thymine DNA glycosylase (TDG) is required for its SUMO-1 modification and colocalization with the promyelocytic leukemia protein”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 280 (7): 5611–21. (February 2005). doi:10.1074/jbc.M408130200. PMID 15569683.

- ^ “Leukemia-associated retinoic acid receptor alpha fusion partners, PML and PLZF, heterodimerize and colocalize to nuclear bodies”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 94 (19): 10255–60. (September 1997). doi:10.1073/pnas.94.19.10255. PMC 23349. PMID 9294197.

- ^ a b c “Interactive Organization of the Circadian Core Regulators PER2, BMAL1, CLOCK and PML”. Scientific Reports 6: 29174. (July 2016). doi:10.1038/srep29174. PMC 4935866. PMID 27383066.

関連文献

[編集]- “The transcriptional role of PML and the nuclear body”. Nature Cell Biology 2 (5): E85–90. (May 2000). doi:10.1038/35010583. PMID 10806494.

- “PML protein isoforms and the RBCC/TRIM motif”. Oncogene 20 (49): 7223–33. (October 2001). doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1204765. PMID 11704850.

- “PML interaction with p53 and its role in apoptosis and replicative senescence”. Oncogene 20 (49): 7250–6. (October 2001). doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1204856. PMID 11704853.

- “The role of PML in tumor suppression”. Cell 108 (2): 165–70. (January 2002). doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00626-8. PMID 11832207.

- “An assessment of progress in the use of alternatives in toxicity testing since the publication of the report of the second FRAME Toxicity Committee (1991)”. Alternatives to Laboratory Animals 30 (4): 365–406. (2002). doi:10.1177/026119290203000403. PMID 12234245.

- “Role of PML and the PML-nuclear body in the control of programmed cell death”. Oncogene 22 (56): 9048–57. (December 2003). doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1207106. PMID 14663483.

- “Targeting the acute promyelocytic leukemia-associated fusion proteins PML/RARα and PLZF/RARα with interfering peptides”. PLOS ONE 7 (11): e48636. (2012). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0048636. PMC 3494703. PMID 23152790.

関連項目

[編集]外部リンク

[編集]- PML protein, human - MeSH・アメリカ国立医学図書館・生命科学用語シソーラス