利用者:World ryoko/sandbox

|

ここはWorld ryokoさんの利用者サンドボックスです。編集を試したり下書きを置いておいたりするための場所であり、百科事典の記事ではありません。ただし、公開の場ですので、許諾されていない文章の転載はご遠慮ください。

登録利用者は自分用の利用者サンドボックスを作成できます(サンドボックスを作成する、解説)。 この利用者の下書き:1 2 3 4 5 6、作成したいページ その他のサンドボックス: 共用サンドボックス | モジュールサンドボックス 記事がある程度できあがったら、編集方針を確認して、新規ページを作成しましょう。 |

(17:15, 21 November 2012)

カナダは、その広い領域から資源を採掘し、輸出している先進国である。そのため、五大湖、セントローレンス海路や太平洋、大西洋、北極海にアクセスできる1,400,000キロメートル (870,000 mi)の道路、10の主要国際空港、300の小空港、72,093 km (44,797 mi)の現役鉄道路線、300の商業港及び湾を含む輸送路が整備されている[1]。2005年には、交通部門がカナダのGDPの4.2%、採鉱や石油・ガスの採掘の3.7%を占めた[2]。

トランスポート・カナダは、カナダの管轄内の多くの交通機関を監視・規制している。トランスポート・カナダは、連邦政府の運輸大臣の指揮下にある。カナダ交通安全協会は、事故を調査、安全対策を強化することにより、カナダの交通機関の安全維持の責任を負っている。

| 産業 | 交通のシェア GDP (%) |

|---|---|

| 航空 | 9 |

| 鉄道 | 13 |

| 水運 | 3 |

| トラック | 35 |

| 運輸・地上乗客輸送 | 12 |

| パイプライン | 11 |

| 観光交通/交通支援 | 17 |

| Total: | 100 |

道路

[編集]

カナダには、合計で1,042,300 km (647,700 mi)の道路があり、このうち高速道路の415,600 km (258,200 mi)(アメリカの州間高速道路、中国の高速道路システムに次ぎ、世界で3番目に長い)を含む415,600 km (258,200 mi)は舗装されている。2008年時点で626,700 km (389,400 mi)は未舗装[3]。

2009年時点で、カナダで登録された自動車は20,706,616台で、うち96%は4.5メトリックトン (4.4ロングトン; 5.0ショートトン)以下、2.4%は4.5メトリックトン (4.4ロングトン; 5.0ショートトン)と15メトリックトン (15ロングトン; 17ショートトン)の間、1.6%は15 t (15ロングトン; 17ショートトン)以上だった。これらの乗り物の走行距離の合計は3332億9千万㎞で、このうち3036億㎞は4.5 t (4.4ロングトン; 5.0ショートトン)以下の車、83億㎞は4.5 t (4.4ロングトン; 5.0ショートトン)と15 t (15ロングトン; 17ショートトン)の間の車、214億㎞は15 t (15ロングトン; 17ショートトン)以上の車である。4.5 t (4.4ロングトン; 5.0ショートトン)から15 t (15ロングトン; 17ショートトン)のトラックについては、距離の88.9%が州内、4.9%が州間、2.8%がカナダとアメリカの間、3.4%がカナダ国外の走行だった。また、 15 t (15ロングトン; 17ショートトン)以上のトラックは、距離の59.1%が州内、20%が州間、13.8%がカナダとアメリカの間、7.1%がカナダ国外の走行である[4]。

カナダでは、3140万立方メートル(198バレル)のガソリンと、991万立方メートル(62.3バレル)の軽油が消費されている[4]。GDPのうち35%はトラック輸送、25%は鉄道、水運、航空となっている(パイプライン、観光交通/交通支援以外)[2]。従って、道路は、カナダの乗客・貨物輸送の優勢な手段となっている。

道路やハイウェイは、ノースウエスト・ハイウェイ・システム(アラスカ・ハイウェイ)やトランスカナダハイウェイプロジェクトが開始されるまで、州や自治体によって管理されていた。第二次世界大戦中の1942年、アラスカ・ハイウェイは、フェアバンクス(アラスカ州)とフォート・セント・ジョン(ブリティッシュコロンビア州)を結ぶ軍事用の道路として開発された[5]。大陸横断ハイウェイ(国・州の運営)は、トランス・カナダ・ハイウェイ法のもと、1949年12月10日に始まった。7,821 km (4,860 mi)のハイウェイが完成したのは1962年で、14億$の予算がかかった[6]。

国際的に、カナダはアメリカ本土48州とアラスカ州にも道路が接続している。運輸省は、オンタリオ州の道路網を維持し、カナダ交通法及び関連法規を処理する目的で 執行官を雇用している[7][8]。ニューブランズウィック州の運輸省も、同様の業務を行っている。

カナダ・ハイウェイに対する法規には、1971年の自動車安全法[9]、1990年のハイウェイ・トラフィック法がある[10]。

カナダの道路の安全性は国際基準で比べて高く、人口1人当たり、走行距離10億㎞当たりの事故の両方の基準で改善している[11]。

航空

[編集]Air transportation made up 9% of the transport sector's GDP generation in 2005. Canada's largest air carrier and its flag carrier is Air Canada, which had 34 million customers in 2006 and, as of April 2010, operates 363 aircraft (including Air Canada Jazz).[12] CHC Helicopter, the largest commercial helicopter operator in the world, is second with 142 aircraft[12] and WestJet, a low-cost carrier formed in 1996, is third with 96 aircraft.[12] Canada's airline industry saw significant change following the signing of the US-Canada open skies agreement in 1995, when the marketplace became less regulated and more competitive.[13]

The Canadian Transportation Agency employs transportation enforcement officers to maintain aircraft safety standards, and conduct periodic aircraft inspections, of all air carriers.[14] The Canadian Air Transport Security Authority is charged with the responsibility for the security of air traffic within Canada. In 1994 the National Airports Policy was enacted[15]

主要空港

[編集]Of over 1,800 registered Canadian aerodromes, certified airports, heliports, and floatplane bases,[16] 26 are specially designated under Canada's National Airports System[17] (NAS): these include all airports that handle 200,000 or more passengers each year, as well as the principal airport serving each federal, provincial, and territorial capital. However, since the introduction of the policy only one, Iqaluit Airport, has been added and no airports have been removed despite dropping below 200,000 passengers.[18] The Government of Canada, with the exception of the three territorial capitals, retains ownership of these airports and leases them to local authorities. The next tier consists of 64 regional/local airports formerly owned by the federal government, most of which have now been transferred to other owners (most often to municipalities).[17]

Below is a table of Canada's ten biggest airports by passenger traffic in 2010.

| Rank | Airport | Location | Total Passengers |

Annual change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Toronto Pearson International Airport | Toronto | 31,842,413[19] | 4.9% |

| 2 | Vancouver International Airport | Vancouver | 16,779,709[20] | 3.7% |

| 3 | Montréal-Pierre Elliott Trudeau International Airport | Montreal | 12,971,229[21] | 6.1% |

| 4 | Calgary International Airport | Calgary | 12,630,695[22] | 3.7% |

| 5 | Edmonton International Airport | Edmonton | 6,089,099[23] | 0.0% |

| 6 | Ottawa Macdonald-Cartier International Airport | Ottawa | 4,473,894[24] | 5.7% |

| 7 | Halifax Stanfield International Airport | Halifax | 3,508,153[25] | 2.6% |

| 8 | Winnipeg James Armstrong Richardson International Airport | Winnipeg | 3,369,974[26] | -0.3% |

| 9 | Victoria International Airport | Victoria | 1,514,713[27] | −1.2% |

| 10 | Kelowna International Airport | Kelowna | 1,391,725[28] | 1.8% |

鉄道

[編集]

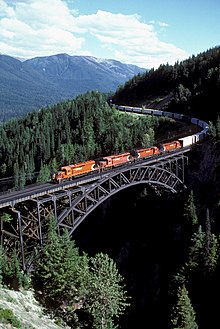

In 2007, Canada had a total of 72,212 km (44,870 mi)[29] of freight and passenger railway, of which 31 km (19 mi) is electrified.[要出典] While intercity passenger transportation by rail is now very limited, freight transport by rail remains common. Total revenues of rail services in 2006 was $10.4 billion, of which only 2.8% was from passenger services. The Canadian National and Canadian Pacific Railway are Canada's two major freight railway companies, each having operations throughout North America. In 2007, 357 billion tonne-kilometres of freight were transported by rail, and 4.33 million passengers travelled 1.44 billion passenger-kilometres (an almost negligible amount compared to the 491 billion passenger-kilometres made in light road vehicles). 34,281 people were employed by the rail industry in the same year.[30]

Nation-wide passenger services are provided by the federal crown corporation Via Rail. Three Canadian cities have commuter rail services: in the Montreal area by AMT, in the Toronto area by GO Transit, and in the Vancouver area by West Coast Express. Smaller railways such as Ontario Northland, Rocky Mountaineer, and Algoma Central also run passenger trains to remote rural areas.

In Canada railways are served by standard gauge, 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm), rails. See also track gauge in Canada.

Canada has rail links with the lower 48 US States, but no connection with Alaska other than a train ferry service from Prince Rupert, British Columbia, although a line has been proposed.[31] There are no other international rail connections.

水上交通

[編集]

In 2005, 139.2 million tonnes of cargo was loaded and unloaded at Canadian ports.[32] The Port of Vancouver is the busiest port in Canada, moving 68 million tonnes or 15% of Canada's total in domestic and international shipping in 2003.[33]

Transport Canada oversees most of the regulatory functions related to marine registration,[34] safety of large vessel,[35] and port pilotage duties.[36] Many of Canada's port facilities are in the process of being divested from federal responsibility to other agencies or municipalities.[37]

Inland waterways comprise 3,000 km (1,900 mi), including the St. Lawrence Seaway. Transport Canada enforces acts and regulations governing water transportation and safety.[38]

| Rank | Port | Province | TEUs | Boxes | Containerized Cargo (Tonnes) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Vancouver | British Columbia | 2,207,730 | 1,282,807 | 17,640,024 |

| 2 | Montreal | Quebec | 1,288,910 | 794,735 | 11,339316 |

| 3 | Halifax | Nova Scotia | 530,722 | 311,065 | 4,572,020 |

| 4 | St. John's | Newfoundland and Labrador | 118,008 | 55,475 | 512,787 |

| 5 | Fraser River | British Columbia | 94,651 | N/A | 742,783 |

| 6 | Saint John | New Brunswick | 44,566 | 24,982 | 259,459 |

| 7 | Toronto | Ontario | 24,585 | 24,585 | 292,834 |

Ferry services

[編集]

- Passenger ferry service

- Vancouver Island to the mainland

- several Sunshine Coast communities to the mainland and to Alaska.

- Internationally to St. Pierre and Miquelon

- Automobile ferry service

- Nova Scotia to Newfoundland and Labrador,

- Quebec to Newfoundland across the Strait of Belle Isle

- Labrador and the island of Newfoundland.

- Chandler to the Magdalen Islands, Quebec

- Prince Edward Island to the Magdalen Islands, Quebec

- Prince Edward Island to Nova Scotia

- Digby, Nova Scotia, to Saint John, New Brunswick

- Train ferry service

- British Columbia to Alaska or Washington state.

Canals

[編集]

The St. Lawrence waterway was at one time the world's greatest inland water navigation system. The main route canals of Canada are those of the St. Lawrence River and the Great Lakes. The others are subsidiary canals.

Ports and harbours

[編集]The National Harbours Board administered Halifax, Saint John, Chicoutimi, Trois-Rivières, Churchill, and Vancouver until 1983. Over 300 harbours across Canada were supervised by the Department of Transport.[5] After divestiture Transport Canada oversees only 17 Canada Port Authorities for the 17 largest shipping ports.[40]

West coast[編集]

East coast[編集]

|

Northern and central[編集]

|

Merchant marine

[編集]Canada's merchant marine comprised a total of 173 ships ( 1,000 総登録トン数 (GRT) or over) 2,129,243 GRT or 716,340 metric tons deadweight (DWT) at the end of 2007.[3]

パイプライン

[編集]

Pipelines are part of the energy extraction and transportation network of Canada and are used to transport natural gas, natural gas liquids, crude oil, synthetic crude and other petroleum based products. Canada has 23,564 km (14,642 mi) of pipeline for transportation of crude and refined oil, and 74,980 km (46,590 mi) for liquefied petroleum gas.[3]

都市交通

[編集]

Most Canadian cities have public transportation, if only a bus system. Six Canadian cities have rapid transit systems and three have commuter rail systems (see below). In 2006, 11% of Canadians used public transportation to get to work. This compares to 80.0% that got to work using a car (72.3% by driving, 7.7% as a passenger), 6.4% that walked and 1.3% that rode a bike.[41]

Rapid transit systems

[編集]There are six urban rapid transit systems operating in Canada: The Montreal Metro, the Toronto Subway, the Vancouver SkyTrain, the Calgary C-Train, the Edmonton Light Rail Transit and the O-Train in Ottawa.

| Location | Transit | Weekday Daily Ridership | Length/Stations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Montreal, Quebec | Montreal Metro | 1,111,700 (Q1 2011)[42] | 69.2 km/ 68 |

| Toronto, Ontario | Toronto Subway/RT* | 1,054,200 (Q4 2011) [43] | 68.3 km/ 69 |

| Vancouver, British Columbia | SkyTrain | 384,100 (Q3 2011)[42] | 68.7 km/ 47 |

| Calgary, Alberta | C-Train | 246,800 (Q3 2011)[42] | 48.8 km/ 37[44] |

| Edmonton, Alberta | Edmonton LRT | 93,600 (2010)[45] | 20.5 km/ 15 |

| Ottawa, Ontario | O-Train | 10,900 (Q3 2011)[42] | 8 km/ 5 |

There is also an Airport Circulator, the LINK Train at Toronto Pearson International Airport. It operates 24 hours a day, 7 days a week and is wheelchair-accessible. It is free of cost.

Commuter train systems

[編集]Commuter trains exist in Montreal, Toronto and Vancouver:

| Location | Transit | Daily Ridership | System Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| Toronto, Ontario | GO Transit | 175,500 (Q3 2011)[42] | 390 km[46] |

| Montreal, Quebec | Agence métropolitaine de transport | 66,600 (Q1 2011)[47] | 214 km |

| Vancouver, British Columbia | West Coast Express | 10,500 (as of 2008)[48] | 69 km[49] |

歴史

[編集]European contact

[編集]Aboriginal peoples in Canada, relied on canoes, kayaks, umiaks and Bull Boats, in addition to the snowshoe, toboggan and sled in winter for transportation prior to European contact. Europeans adopted these technologies as they pushed deeper into the continent's interior, and were thus able to travel via the waterways that fed from the St. Lawrence River and Hudson Bay.[50]

In the 19th century and early 20th century transportation relied on harnessing oxen to Red River ox carts or horse to waggon. Maritime transportation was via manual labour such as canoe or wind on sail. Water or land travel speeds was approximately 8 - 15 km/h (5 - 9 mph).[51]

Settlement was along river routes. Agricultural commodities were perishable, and trade centres were within 50 km (31 mi). Rural areas centred around villages, and they were approximately 10 km (6 mi) apart. The advent of steam railways and steamships connected resources and markets of vast distances in the late 19th century.[51] Railways also connected city centres, in such a way that the traveller went by sleeper, railway hotel, to the cities. Crossing the country by train took four or five days, as it still does by car. People generally lived within 5 mi (8 km) of the downtown core thus the train could be used for inter-city travel and the tram for commuting.

The advent of the interstate or Trans-Canada Highway in Canada in 1963 established ribbon development, truck stops, and industrial corridors along throughways.

Evolution

[編集]Different parts of the country are shut off from each other by Cabot Strait, the Strait of Belle Isle, by areas of rough, rocky forest terrain, such as the region lying between New Brunswick and Quebec, the areas north of Lakes Huron and Superior, dividing the industrial region of Ontario and Quebec from the agricultural areas of the prairies, and the barriers interposed by the mountains of British Columbia — The Canada Year Book 1956[5]

The Federal Department of Transport established November 2, 1936, supervised railways, canals, harbours, marine and shipping, civil aviation, radio and meteorology. The Transportation Act of 1938 and the amended Railway Act, placed control and regulation of carriers in the hands of the Board of Transport commissioners for Canada. The Royal Commission on Transportation was formed December 29, 1948, to examine transportation services to all areas of Canada to eliminate economic or geographic disadvantages. The Commission also reviewed the Railway Act to provide uniform yet competitive freight-rates.[5]

関連項目

[編集]- Royal tours of Canada: Transportation

- Royal Canadian Air Force VIP aircraft

- Royal Commission on Railways

- Transportation in the United States

- The Romance of Transportation in Canada, a National Film Board of Canada animated short

- Taxicabs of Canada

出典

[編集]- ^ “Transportation in Canada”. Statistics Canada. 2008年3月26日閲覧。

- ^ a b c “An Analysis of the Transportation Sector in 2005” (PDF). Statistics Canada. 2008年4月9日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年3月27日閲覧。

- ^ a b c “CIA - The World Factbook”. The World Factbook. CIA. 2011年1月13日閲覧。

- ^ a b “Canadian Vehicle Survey: Annual” (PDF). Statistics Canada (2009年). 2011年1月13日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d Howe, C.D., the Right Honourable Minister of Trade and Commerce; Canada Year Book Section, Information Services Division Dominion Bureau of Statistics (1956). "The Canada Year Book 1956 The Official Handbook of Present Conditions and Recent Progress" (Document). Ottawa, Ontario: Kings Printer and Controller of Stationery. page 713 to 791。

- ^ Coneghan, Daria (2006). "Trans-Canada Highway" (Document). Canadian Plains Research Center, University of Regina.

{{cite document}}: 不明な引数|accessdate=は無視されます。 (説明); 不明な引数|url=は無視されます。 (説明); 不明な引数|work=は無視されます。 (説明) - ^ “Regional Enforcement Officers”. Canadian Transportation Agency. 2007年10月1日閲覧。

- ^ “Enforcement blitz improves road safety”. Canada NewsWire. 2007年10月1日閲覧。 [リンク切れ]

- ^ “Motor Vehicle Safety Act”. 2007年12月28日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月18日閲覧。

- ^ “Highway Traffic Act”. 2008年1月18日閲覧。

- ^ “Transport in Canada”. International Transport Statistics Database. iRAP. 2008年10月6日閲覧。

- ^ a b c Transport Canada listing of aircraft owned by Air Canada and Air Canada Jazz (enter Air Canada (226 aircraft), Jazz Air LP (137 aircraft), Canadian Helicopters or Westjet in the box titled "Owner Name")

- ^ “Travelog - Volume 18, Number 3”. Statistics Canada. 2008年4月9日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年3月27日閲覧。

- ^ “Enforcement”. Canadian Transportation Agency. 2007年10月1日閲覧。

- ^ “National Airports Policy”. 2008年1月18日閲覧。

- ^ Canada Flight Supplement. Effective 0901Z 29 March 2018 to 0901Z 24 May 2018

- ^ a b “Airport Divestiture Status Report”. Tc.gc.ca (2011年1月12日). 2011年2月19日閲覧。

- ^ “Airports in the national airports category (Appendix A)”. Tc.gc.ca (2010年12月16日). 2011年2月19日閲覧。

- ^ Lester B. Pearson International Airport (Enplaned + Deplaned ) Passengers

- ^ YVR Passengers (Enplaned + Deplaned) 1992-2010

- ^ ENPLANED / DEPLANED PASSENGERS* (revenue and non-revenue)

- ^ Calgary International Airport Local E&D Passenger Statistics1

- ^ Edmonton International Airport Enplaned and Deplaned Passengers 2010 Actual Compared to 2009 Actual

- ^ Ottawa Macdonald-Cartier International Airport Total Passenger Volume (2006-2010)

- ^ Airport Statistics Halifax

- ^ Passenger Statistics Winnipeg

- ^ YYJ Passengers (Enplaned + Deplaned) 2004 - 2010

- ^ Facts and Statistics Kelowna

- ^ “Rail transportation, length of track operated for freight and passenger transportation, by province and territory”. statcan.ca. Statistics Canada. 2009年3月13日閲覧。 [リンク切れ]

- ^ “Railway carriers, operating statistics”. Statistics Canada. 2008年2月23日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年3月26日閲覧。

- ^ “AlaskaCanadaRail.org”. AlaskaCanadaRail.org (2005年7月1日). 2011年2月19日閲覧。

- ^ “Domestic and international cargo, tonnage loaded and unloaded by water transport, by province and territory.”. Statistics Canada. 2008年3月29日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年4月4日閲覧。

- ^ “Vancouver: Canada's busiest port”. Statistics Canada. 2008年4月9日閲覧。 [リンク切れ]

- ^ “Small Vessel Monitoring & Inspection Program”. Transport Canada. 2007年9月13日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2007年10月1日閲覧。

- ^ “Port State Control”. Transport Canada. 2007年10月1日閲覧。

- ^ “Marine Personnel Standards and Pilotage”. Transport Canada. 2007年10月1日閲覧。

- ^ “Airport and Port Programs”. Transport Canada. 2007年10月1日閲覧。

- ^ “Marine Acts and Regulations”. Transport Canada. Government of Canada. 2008年1月15日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月18日閲覧。

- ^ AAPA (May 14, 2007). “North American Port Container Traffic 2006”. 2009年3月23日閲覧。 [リンク切れ]

- ^ “Porst”. Transport Canada. 2010年2月2日閲覧。

- ^ “Commuting Patterns and Places of Work of Canadians, 2006 Census”. Statistics Canada. 2011年11月4日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e “APTA Public Transportation Ridership Report”. APTA (Third Quarter, 2011). December 8, 2011閲覧。

- ^ http://www.apta.com/resources/statistics/Documents/Ridership/2010_q1_ridership_APTA.pdf

- ^ LRT Technical Data Retrieved on 2009-01-17.

- ^ “LRT is the Way We Move”. City of Edmonton (2011年2月15日). 2011年2月15日閲覧。

- ^ GO by the numbers Retrieved on 2009-01-17.

- ^ “APTA Public Transportation Ridership Report”. APTA (First Quarter, 2011). December 8, 2011閲覧。

- ^ West Coast Express: Facts and Figures 2008 Retrieved 8 December 2009

- ^ West Coast Express: Stations and Parking Information Retrieved 9 December 2009

- ^ Virtual Vault, an online exhibition of Canadian historical art at Library and Archives Canada

- ^ a b Rodrigue, Dr. Jean-Paul (1998-2008). “Historical Geography of Transportation - Part I”. Dept. of Economics & Geography. Hofstra University. 2008年1月12日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月18日閲覧。

外部リンク

[編集]<nowiki>

- "Transportation and Maps" in Virtual Vault, an online exhibition of Canadian historical art at Library and Archives Canada

- North American transportation statistics

Template:Canada topic Template:Canada topics Template:Americas topic </nowki>