利用者:Smilesworth/sandbox5

- モルディブでゴーストネットに絡まったヒメウミガメ(左上)Olive ridley sea turtle entangled in a ghost net in the Maldives

- エジプト・サファガ近郊、Sharm el-Nagaビーチに打ち上げられたプラスチック廃棄物(右上)Plastic pollution of Sharm el-Naga beach, near Safaga, Egypt

- カメルーン・ドゥアラ、プラスチックで完全に閉塞したウォリ川の支流(左下)A tributary of the Wouri River in Douala, Cameroon, completely clogged with plastic

- モルディブ・ティラフシ島、政府公認の「ゴミの島」のプラスチック廃棄物の山(右下)Piles of plastic waste on the government-authorized "garbage island" of Thilafushi

プラスチック汚染(プラスチックおせん、英: plastic pollution)とは、プラスチック製品やプラスチック粒子(ペットボトル、ポリ袋、マイクロビーズなど)が環境中に蓄積し、ヒトや野生生物、その生息地に悪影響を与えることを指す[1][2]。汚染物質としてのプラスチックは、マイクロデブリ(micro debris、直径<2 mm)、メソデブリ(meso debris、2–20 mm)、マクロデブリ(macro debris、>20 mm)のように、そのサイズによって分類する方法がとられる場合があるが、統一的な分類基準が存在するわけではない[3]。プラスチックは安価で耐久性が高く、さまざまな用途への応用が可能である。こうした理由により、製造者は他の素材よりもプラスチックを選択する[4]。しかしながら、大部分のプラスチックの化学構造は自然界の多くの分解過程に対する耐性が高く、そのため分解には時間がかかる[5]。こうした2つの要因により、大量のプラスチックが不適切な処理が行われた廃棄物として環境に流入し、生態系に残留することとなっている。

Plastic pollution is the accumulation of plastic objects and particles (e.g. plastic bottles, bags and microbeads) in the Earth's environment that adversely affects humans, wildlife and their habitat.[1][2] Plastics that act as pollutants are categorized by size into micro-, meso-, or macro debris.[3] Plastics are inexpensive and durable, making them very adaptable for different uses; as a result, manufacturers choose to use plastic over other materials.[4] However, the chemical structure of most plastics renders them resistant to many natural processes of degradation and as a result they are slow to degrade.[5] Together, these two factors allow large volumes of plastic to enter the environment as mismanaged waste and for it to persist in the ecosystem.

プラスチック汚染は土地、河川、海洋に悪影響を与える場合がある。毎年、沿岸地域から海洋へ流入するプラスチック廃棄物は110万トンから880万トンと推計されている[6]。2013年末の時点で、世界中の海洋のプラスチックごみは8600万トンと推計されており、1950年から2013年にかけて世界中で生産されたプラスチックの1.4%が海洋に流入し、蓄積していると推定されている[7]。一部の研究者は、2050年までに海洋中のプラスチックの重量が魚類の重量を上回る可能性があることを示唆している[8]。生物、特に海洋動物は、プラスチック製品が絡みつくといった機械的影響、プラスチック廃棄物の摂取と関係した問題、プラスチックに含まれる化学物質への曝露による生理への影響などの被害を受ける可能性がある。分解されたプラスチック廃棄物は、直接的消費(水道水など)、間接的消費(動物の食用など)、さまざまなホルモン機構の破壊の両方を通じて、ヒトに直接的な影響を与える場合がある。

Plastic pollution can afflict land, waterways and oceans. It is estimated that 1.1 to 8.8 million tonnes of plastic waste enters the ocean from coastal communities each year.[6] It is estimated that there is a stock of 86 million tons of plastic marine debris in the worldwide ocean as of the end of 2013, with an assumption that 1.4% of global plastics produced from 1950 to 2013 has entered the ocean and has accumulated there.[9] Some researchers suggest that by 2050 there could be more plastic than fish in the oceans by weight.[8] Living organisms, particularly marine animals, can be harmed either by mechanical effects such as entanglement in plastic objects, problems related to ingestion of plastic waste, or through exposure to chemicals within plastics that interfere with their physiology. Degraded plastic waste can directly affect humans through both direct consumption (i.e. in tap water), indirect consumption (by eating animals), and disruption of various hormonal mechanisms.

2019年時点で、毎年3億6800万トンのプラスチックが生産されている。51%はアジアで生産されており、中国は世界最大の生産国である[10]。1950年代から2018年までに世界中で63億トンのプラスチックが生産され、そのうち9%がリサイクルされ、12%が焼却処分されたと推計されている[11]。大量のプラスチック廃棄物は環境中に流入し、生態系のあらゆる部分で問題を引き起こしている。一例として、90%の海鳥の体内にプラスチックごみが含まれていることが研究から示唆されている[12][13]。一部の地域では、プラスチック消費の削減、ゴミの清掃、リサイクルの推進など、野放図なプラスチック汚染を食い止めるための大きな取り組みが行われている[14][15]。

As of 2019, 368 million tonnes of plastic is produced each year; 51% in Asia, where China is the world's largest producer.[10] From the 1950s up to 2018, an estimated 6.3 billion tonnes of plastic has been produced worldwide, of which an estimated 9% has been recycled and another 12% has been incinerated.[11] This large amount of plastic waste enters the environment and causes problems throughout the ecosystem; for example, studies suggest that the bodies of 90% of seabirds contain plastic debris.[12][13] In some areas there have been significant efforts to reduce the prominence of free range plastic pollution, through reducing plastic consumption, litter cleanup, and promoting plastic recycling.[14][15]

2020年時点で、世界中で生産されたプラスチックの重量は全ての陸上動物と海洋動物を合計した重量を超えている[16]。2019年5月のバーゼル条約の改正ではプラスチック廃棄物の輸出入が規制されることとなったが、これは主に先進国から開発途上国へのプラスチック廃棄物の運搬の防止を意図したものである。ほぼすべての国家がこの協定に参加ている[17][18][19][20]。2022年3月2日にナイロビにおいて、プラスチック汚染を終結させることを目標にした法的拘束力のある協定を2024年末までに作成することを175か国が誓約した[21]。

As of 2020, the global mass of produced plastic exceeds the biomass of all land and marine animals combined.[16] A May 2019 amendment to the Basel Convention regulates the exportation/importation of plastic waste, largely intended to prevent the shipping of plastic waste from developed countries to developing countries. Nearly all countries have joined this agreement.[17][18][19][20] On 2 March 2022 in Nairobi, 175 countries pledged to create a legally binding agreement by the end of the year 2024 with a goal to end plastic pollution.[21]

COVID-19によるパンデミックの間、防護具や梱包材の需要の増加のためプラスチック廃棄物の量は増加した[22]。最終的に海洋に流出するプラスチックの量は増加し、特に医療廃棄物やマスクなどのプラスチックが増加した[23][24]。一部のニュースでは、プラスチック産業は健康への懸念や使い捨てのマスクや梱包材への要求を利用して、使い捨てプラスチック製品の生産を増やそうとしていることが指摘されている[25][26][27][28]。

The amount of plastic waste produced increased during the COVID-19 pandemic due to increased demand for protective equipment and packaging materials.[22] Higher amounts of plastic ended up in the ocean, especially plastic from medical waste and masks.[23][24] Several news reports point to a plastic industry trying to take advantage of the health concerns and desire for disposable masks and packaging to increase production of single use plastic.[25][26][27][28]

原因Causes

[編集]

20世紀中に生み出されたプラスチック廃棄物の量にかんしてはさまざまな推計がなされている。その1つでは、1950年代以降に10億トンのプラスチックが廃棄されたとされる[29]。他の推計では、累積生産量は83億トン、そのうち63億トンが廃棄物となり、リサイクルされたのはわずか9%であるとされる[30][31]。

There are differing estimates of how much plastic waste has been produced in the last century. By one estimate, one billion tons of plastic waste have been discarded since the 1950s.[29] Others estimate a cumulative human production of 8.3 billion tons of plastic, of which 6.3 billion tons is waste, with only 9% getting recycled.[30][31]

2018年までに生み出された廃棄物の81%はポリマー樹脂、13%はポリマー繊維、5.8%がプラスチック添加剤である[32]。2018年には3億4300万トンのプラスチック廃棄物が生み出され、その90%は使用済みプラスチック廃棄物(工業、農業、商業、一般廃棄物)である。残りは、樹脂生産やプラスチック製品の製造工程など、消費者に渡る前の工程で発生したもの(色、硬さや加工特性の不適合による廃棄物など)である[31]。

It is estimated that this waste is made up of 81% polymer resin, 13% polymer fibres and 32% additives. In 2018 more than 343 million tonnes of plastic waste were generated, 90% of which was composed of post-consumer plastic waste (industrial, agricultural, commercial and municipal plastic waste). The rest was pre-consumer waste from resin production and manufacturing of plastic products (e.g. materials rejected due to unsuitable colour, hardness, or processing characteristics).[31]

プラスチック梱包材は使用済みプラスチック廃棄物の大部分を占める。アメリカ合衆国では、プラスチック梱包材は都市廃棄物の5%を占めると推計されている。こうした梱包材には、ペットボトル、プラスチック製の鉢、桶、トレイ、フィルム、買い物袋、ごみ袋、気泡緩衝材、ラップ、発泡プラスチック(発泡スチロールなど)が含まれる。プラスチック廃棄物は、農業(灌漑パイプ、温室カバー、柵、ペレット、マルチ)、建築(パイプ、ペンキ、床材や屋根材、断熱材、シーリング材)、輸送(タイヤ、舗装、路面標示)、電気・電子機器(E-waste)、製薬・ヘルスケアなどの産業でも生み出される。これらの分野から生み出されるプラスチック廃棄物の総量は不明確である[31]。

A large proportion of post-consumer plastic waste consists of plastic packaging. In the United States plastic packaging has been estimated to make up 5% of MSW. This packaging includes plastic bottles, pots, tubs and trays, plastic films shopping bags, rubbish bags, bubble wrap, and plastic or stretch wrap and plastic foams e.g. expanded polystyrene (EPS). Plastic waste is generated in sectors including agriculture (e.g. irrigation pipes, greenhouse covers, fencing, pellets, mulch; construction (e.g. pipes, paints, flooring and roofing, insulants and sealants); transport (e.g. abraded tyres, road surfaces and road markings); electronic and electric equipment (e-waste); and pharmaceuticals and healthcare. The total amounts of plastic waste generated by these sectors is uncertain.[31]

国家や世界レベルで環境中へのプラスチック漏出の定量を試みた研究はいくつか行われているが、すべてのプラスチック漏出の発生源とその量を明らかにすることの困難さが浮き彫りとなっている。世界レベルで行われた1つの研究では2015年に不適切な処理がなされたプラスチック廃棄物は6000万トンから9900万トンと推計されている。また、2016年に水圏生態系に流入したプラスチック廃棄物は1900万トンから2300万トンと推計されている。一方、他の研究では毎年海洋に流入するプラスチック廃棄物は900万トンから1400万トンと推計されている[31]。

Several studies have attempted to quantify plastic leakage into the environment at both national and global levels which have highlight the difficulty of determining the sources and amounts of all plastic leakage. One global study has estimated that between 60 and 99 million tonnes of mismanaged plastic waste were produced in 2015. Borrelle et al. 2020 has estimated that 19–23 million tonnes of plastic waste entered aquatic ecosystems in 2016. while the Pew Charitable Trusts and SYSTEMIQ (2020) have estimated that 9–14 million tonnes of plastic waste ended up in the oceans the same year.

プラスチック廃棄物を削減するための国際的な取り組みが行われているものの、環境に対する損失は増加することが予測されている。大規模な介入が行われない限り、2040年頃には毎年2300万トンから3700万トンのプラスチック廃棄物が海洋に流入する可能性があり、2060年頃には毎年1億5500万トンから2億6500万トンが環境中に放出される可能性があることがモデリングから示されている。従来通りのシナリオでは、こうした増加は消費者の需要によってプラスチック製品の生産が増え続けること、そして廃棄物管理の改善が不十分であることが原因となる可能性が高い。環境中に放出されたプラスチック廃棄物は生態系に既に重大な影響を及ぼしており、こうした規模での増加によって劇的な結果がもたらされる可能性がある[31]。

Despite global efforts to reduce the generation of plastic waste, losses to the environment are predicted to increase. Modelling indicates that, without major interventions, between 23 and 37 million tonnes per year of plastic waste could enter the oceans by 2040 and between 155 and 265 million tonnes per year could be discharged into the environment by 2060. Under a business as usual scenario, such increases would likely be attributable to a continuing rise in production of plastic products, driven by consumer demand, accompanied by insufficient improvements in waste management. As the plastic waste released into the environment already has a significant impact on ecosystems, an increase of this magnitude could have dramatic consequences.[31]

プラスチック廃棄物の取引は海洋ごみの発生の元凶であるとされている。廃棄プラスチックを輸入する国家は、素材の処理能力が不足していることが多い。そのため国連は、特定の基準を満たさない限り、プラスチック廃棄物の取引を禁止している。

The trade in plastic waste has been identified as "a main culprit" of marine litter.[注釈 1] Countries importing the waste plastics often lack the capacity to process all the material. As a result, the United Nations has imposed a ban on waste plastic trade unless it meets certain criteria.[注釈 2]

プラスチックごみの種類Types of plastic debris

[編集]

マクロデブリ(直径>20 mm)やメガデブリ(>100 mm)は北半球で最も密度が高く、中心市街地や海岸・河岸地域周辺に密集している。プラスチックごみは海流によって運搬されるため、プラスチックは一部の島の沖合でもみられる。マクロプラスチックやメガプラスチックは、梱包材や履物のほか、船から流れ出たり、埋立地に捨てられたりした日用品に含まれている。漁業関連のものは、離島の周辺で発見される可能性が高い[34][35]。

There are three major forms of plastic that contribute to plastic pollution: micro-, macro-, and mega-plastics. Mega- and micro plastics have accumulated in highest densities in the Northern Hemisphere, concentrated around urban centers and water fronts. Plastic can be found off the coast of some islands because of currents carrying the debris. Both mega- and macro-plastics are found in packaging, footwear, and other domestic items that have been washed off of ships or discarded in landfills. Fishing-related items are more likely to be found around remote islands.[34][35] These may also be referred to as micro-, meso-, and macro debris.

プラスチックごみは、一次(primary)、二次(secondary)に分類されることもある。一次プラスチックは集められた際に当初の形態を保っているものであり、ボトルキャップ、たばこのフィルター、マイクロビーズなどがその例として挙げられる。二次プラスチックは一次プラスチックの分解によって生じた、より小さなプラスチックを指す[36]。

Plastic debris is categorized as either primary or secondary. Primary plastics are in their original form when collected. Examples of these would be bottle caps, cigarette butts, and microbeads.[37] Secondary plastics, on the other hand, account for smaller plastics that have resulted from the degradation of primary plastics.[36]

マイクロデブリMicrodebris

[編集]

マイクロデブリはサイズが2 mmから5 mmのプラスチック片である[35]。メソデブリまたはマクロデブリとして廃棄されたプラスチックごみは、分解や衝突によってより小さな破片となってマイクロデブリとなる[3]。マイクロデブリはナードルとも呼ばれる[3]。ナードルは新たなプラスチック製品へリサイクルされるが、サイズが小さいため生産過程で容易に環境中へ放出される。そして多くの場合、河川などを介して海洋へ流出する[3]。洗浄製品や化粧品に由来するマイクロデブリはスクラブとも呼ばれる。マイクロデブリやスクラブは非常に小さいため、濾過摂食を行う生物に取り込まれることが多い[3]。

Microdebris are plastic pieces between 2 mm and 5 mm in size.[35] Plastic debris that starts off as meso- or macrodebris can become microdebris through degradation and collisions that break it down into smaller pieces.[3] Microdebris is more commonly referred to as nurdles.[3] Nurdles are recycled to make new plastic items, but they easily end up released into the environment during production because of their small size. They often end up in ocean waters through rivers and streams.[3] Microdebris that come from cleaning and cosmetic products are also referred to as scrubbers. Because microdebris and scrubbers are so small in size, filter-feeding organisms often consume them.[3]

ナードルは輸送時に海洋へこぼれ出たり、また陸上からも海洋へ流入する。Ocean Conservancyによる報告では、中国、インドネシア、タイ、ベトナムによるプラスチックの海洋への投棄量は、他のすべての国家の合計よりも多いとされている[38]。海洋中のプラスチックの10%がナードルであり、ポリ袋や食品容器とともに最も一般的なプラスチック汚染種の1つとなっている[39]。こうしたマイクロプラスチックは海洋に蓄積し、ビスフェノールA、ポリスチレン、DDT、PCBなどの難分解性・生物蓄積性・有害性物質の蓄積を引き起こす。これらの物質は疎水的性質を持ち、健康に悪影響を与える場合がある[39][40]。

Nurdles enter the ocean by means of spills during transportation or from land based sources. The Ocean Conservancy reported that China, Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam dump more plastic in the sea than all other countries combined.[38] It is estimated that 10% of the plastics in the ocean are nurdles, making them one of the most common types of plastic pollution, along with plastic bags and food containers.[41][42] These micro-plastics can accumulate in the oceans and allow for the accumulation of Persistent Bio-accumulating Toxins such as bisphenol A, polystyrene, DDT, and PCB's which are hydrophobic in nature and can cause adverse health affects.[43][40]

Amounts, locations, tracking, and correlations of the microdebris

[編集]A 2004 study by Richard Thompson from the University of Plymouth, UK, found a great amount of microdebris on beaches and in waters in Europe, the Americas, Australia, Africa, and Antarctica.[5] Thompson and his associates found that plastic pellets from both domestic and industrial sources were being broken down into much smaller plastic pieces, some having a diameter smaller than human hair.[5] If not ingested, this microdebris floats instead of being absorbed into the marine environment. Thompson predicts there may be 300,000 plastic items per square kilometre of sea surface and 100,000 plastic particles per square kilometre of seabed.[5] International Pellet Watch collected samples of polythene pellets from 30 beaches in 17 countries which were analysed for organic micro-pollutants. It was found that pellets found on beaches in the US, Vietnam and southern Africa contained compounds from pesticides suggesting a high use of pesticides in the areas.[44] In 2020 scientists created what may be the first scientific estimate of how much microplastic currently resides in Earth's seafloor, after investigating six areas of ~3 km depth ~300 km off the Australian coast. They found the highly variable microplastic counts to be proportionate to plastic on the surface and the angle of the seafloor slope. By averaging the microplastic mass per cm3, they estimated that Earth's seafloor contains ~14 million tons of microplastic – about double the amount they estimated based on data from earlier studies – despite calling both estimates "conservative" as coastal areas are known to contain much more microplastic. These estimates are about one to two times the amount of plastic thought – per Jambeck et al., 2015 – to currently enter the oceans annually.[45][46][47]

Macrodebris

[編集]Plastic debris is categorized as macrodebris when it is larger than 20 mm. These include items such as plastic grocery bags.[3] Macrodebris are often found in ocean waters, and can have a serious impact on the native organisms. Fishing nets have been prime pollutants. Even after they have been abandoned, they continue to trap marine organisms and other plastic debris. Eventually, these abandoned nets become too difficult to remove from the water because they become too heavy, having grown in weight up to 6 tonnes.[3]

Plastic production

[編集]9.2 billion tonnes of plastic are estimated to have been made between 1950 and 2017. More than half this plastic has been produced since 2004. Of all the plastic discarded so far, 14% has been incinerated and less than 10% has been recycled.[31]

Decomposition of plastics

[編集]

Plastics themselves contribute to approximately 10% of discarded waste. Many kinds of plastics exist depending on their precursors and the method for their polymerization. Depending on their chemical composition, plastics and resins have varying properties related to contaminant absorption and adsorption. Polymer degradation takes much longer as a result of saline environments and the cooling effect of the sea. These factors contribute to the persistence of plastic debris in certain environments.[35] Recent studies have shown that plastics in the ocean decompose faster than was once thought, due to exposure to sun, rain, and other environmental conditions, resulting in the release of toxic chemicals such as bisphenol A. However, due to the increased volume of plastics in the ocean, decomposition has slowed down.[48] The Marine Conservancy has predicted the decomposition rates of several plastic products. It is estimated that a foam plastic cup will take 50 years, a plastic beverage holder will take 400 years, a disposable nappy will take 450 years, and fishing line will take 600 years to degrade.[5]

Persistent organic pollutants

[編集]It was estimated that global production of plastics is approximately 250 mt/yr. Their abundance has been found to transport persistent organic pollutants, also known as POPs. These pollutants have been linked to an increased distribution of algae associated with red tides.[35]

Commercial pollutants

[編集]In 2019, the group Break Free From Plastic organized over 70,000 volunteers in 51 countries to collect and identify plastic waste. These volunteers collected over "59,000 plastic bags, 53,000 sachets and 29,000 plastic bottles," as reported by The Guardian. Nearly half of the items were identifiable by consumer brands. The most common brands were Coca-Cola, Nestlé, and Pepsico.[49][50] According to the global campaign coordinator for the project Emma Priestland in 2020, the only way to solve the problem is stopping production of single use plastic and using reusable products instead.[51][52] China is the biggest consumer of single-use plastics.[53]

Coca-Cola answered that "more than 20% of our portfolio comes in refillable or fountain packaging", they are decreasing the amount of plastic in secondary packaging.[54]

Nestlé responded that 87% of their packaging and 66% of their plastic packaging can be reused or recycled and by 2025 they want to make it 100%. By that year they want to reduce the consumption of virgin plastic by one third.[要出典][55]

Pepsico responded that they want to decrease "virgin plastic in our beverage business by 35% by 2025” and also expanding reuse and refill practices what should prevent 67 billion single use bottles by 2025.[55]

Major plastic polluter countries

[編集]

The United States National Academy of Sciences estimated in 2022 that the worldwide entry of plastic into the ocean was 8 million metric tons of plastic per year.[56] A 2021 study by The Ocean Cleanup estimated that rivers convey between 0.8 and 2.7 million metric tons of plastic into the ocean, and ranked these river's countries. The top ten were, from the most to the least: Philippines, India, Malaysia, China, Indonesia, Myanmar, Brazil, Vietnam, Bangladesh, and Thailand.[57]

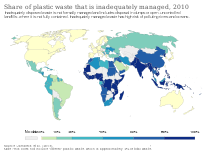

Mismanaged plastic waste polluters

[編集]Top 12 mismanaged plastic waste polluters

In 2018 approximately 513 million tonnes of plastics wind up in the oceans every year out of which the 83,1% is from the following 20 countries: China is the most mismanaged plastic waste polluter leaving in the sea the 27.7% of the world total, second Indonesia with the 10.1%, third Philippines with 5.9%, fourth Vietnam with 5.8%, fifth Sri Lanka 5.0%, sixth Thailand with 3.2%, seventh Egypt with 3.0%, eighth Malaysia with 2.9%, ninth Nigeria with 2.7%, tenth Bangladesh with 2.5%, eleventh South Africa with 2.0%, twelfth India with 1.9%, thirteenth Algeria with 1.6%, fourteenth Turkey with 1.5%, fifteenth Pakistan with 1.5%, sixteenth Brazil with 1.5%, seventeenth Myanmar with 1.4%, eighteenth Morocco with 1.0%, nineteenth North Korea with 1.0%, twentieth United States with 0.9%. The rest of world's countries combined wind up the 16.9% of the mismanaged plastic waste in the oceans, according to a study published by Science in 2015.[6][58][59]

All the European Union countries combined would rank eighteenth on the list.[6][58]

In 2020, a new study revised the potential 2016 U.S. contribution to mismanaged plastic.[17] It estimated an annual 0.15–0.99 metric tons was mismanaged in the countries to which the U.S. exported plastics for recycling, and an 0.14 and 0.41 metric tons was illegally dumped in the U.S. itself. Thus the amount of U.S.-generated plastic estimated to enter the ocean environment could range as high as 1.45 Mt, placing the U.S. behind Indonesia and India in oceanic pollution, or as low as 0.51 Mt, placing the U.S. behind Indonesia, India, Thailand, China, Brazil, Philippines, Egypt, Japan, Russia, and Vietnam. Since 2016 China ceased importing plastics for recycling and since 2019 international treaties signed by 187 countries restricted the export of plastics for recycling.[60][61]

A 2019 study calculated the mismanaged plastic waste, in millions of metric tonnes (Mt) per year:

- 52 Mt – Asia

- 17 Mt – Africa

- 7.9 Mt – Latin America & Caribbean

- 3.3 Mt – Europe

- 0.3 Mt – US & Canada

- 0.1 Mt – Oceania (Australia, New Zealand, etc.)[62]

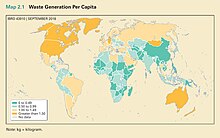

Total plastic waste polluters

[編集]Around 275 million tonnes of plastic waste is generated each year around the world; between 4.8 million and 12.7 million tonnes is dumped into the sea. About 60% of the plastic waste in the ocean comes from the following top 5 countries.[63] The table below list the top 20 plastic waste polluting countries in 2010 according to a study published by Science, Jambeck et al (2015).[6][58]

| Position | Country | Plastic pollution (in 1000 tonnes per year) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | China | 8820 |

| 2 | Indonesia | 3220 |

| 3 | Philippines | 1880 |

| 4 | Vietnam | 1830 |

| 5 | Sri Lanka | 1590 |

| 6 | Thailand | 1030 |

| 7 | Egypt | 970 |

| 8 | Malaysia | 940 |

| 9 | Nigeria | 850 |

| 10 | Bangladesh | 790 |

| 11 | South Africa | 630 |

| 12 | India | 600 |

| 13 | Algeria | 520 |

| 14 | Turkey | 490 |

| 15 | Pakistan | 480 |

| 16 | Brazil | 470 |

| 17 | Myanmar | 460 |

| 18 | Morocco | 310 |

| 19 | North Korea | 300 |

| 20 | United States | 280 |

All the European Union countries combined would rank eighteenth on the list.[6][58]

In a study published by Environmental Science & Technology, Schmidt et al (2017) calculated that 10 rivers: two in Africa (the Nile and the Niger) and eight in Asia (the Ganges, Indus, Yellow, Yangtze, Hai He, Pearl, Mekong and Amur) "transport 88–95% of the global plastics load into the sea.".[64][65][66][67]

The Caribbean Islands are the biggest plastic polluters per capita in the world. Trinidad and Tobago produces 1.5 kilograms of waste per capita per day, is the biggest plastic polluter per capita in the world. At least 0.19 kg per person per day of Trinidad and Tobago's plastic debris end up in the ocean, or for example Saint Lucia which generates more than four times the amount of plastic waste per capita as China and is responsible for 1.2 times more improperly disposed plastic waste per capita than China. Of the top thirty global polluters per capita, ten are from the Caribbean region. These are Trinidad and Tobago, Antigua and Barbuda, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Guyana, Barbados, Saint Lucia, Bahamas, Grenada, Anguilla and Aruba, according to a set of studies summarized by Forbes (2019).[68]

Effects

[編集]Effects on the environment

[編集]The distribution of plastic debris is highly variable as a result of certain factors such as wind and ocean currents, coastline geography, urban areas, and trade routes. Human population in certain areas also plays a large role in this. Plastics are more likely to be found in enclosed regions such as the Caribbean. It serves as a means of distribution of organisms to remote coasts that are not their native environments. This could potentially increase the variability and dispersal of organisms in specific areas that are less biologically diverse. Plastics can also be used as vectors for chemical contaminants such as persistent organic pollutants and heavy metals.[35]

Plastic pollution has also greatly negatively affected our environment. "The pollution is significant and widespread, with plastic debris found on even the most remote coastal areas and in every marine habitat".[69] This information tells us about how much of a consequential change plastic pollution has made on the ocean and even the coasts.

In January 2022 a group of scientists defined a planetary boundary for "novel entities" (pollution, including plastic pollution) and found it has already been exceeded. According to co-author Patricia Villarubia-Gómez from the Stockholm Resilience Centre, "There has been a 50-fold increase in the production of chemicals since 1950. This is projected to triple again by 2050". There are at least 350,000 artificial chemicals in the world. They have mostly "negative effects on planetary health". Plastic alone contain more than 10,000 chemicals and create large problems. The researchers are calling for limit on chemical production and shift to circular economy, meaning to products that can be reused and recycled.[70]

In the marine environment, plastic pollution causes "Entanglement, toxicological effects via ingestion of plastics, suffocation, starvation, dispersal, and rafting of organisms, provision of new habitats, and introduction of invasive species are significant ecological effects with growing threats to biodiversity and trophic relationships. Degradation (changes in the ecosystem state) and modifications of marine systems are associated with loss of ecosystem services and values. Consequently, this emerging contaminant affects the socio-economic aspects through negative impacts on tourism, fishery, shipping, and human health".[71]

Plastic pollution as a cause of climate change

[編集]In 2019 a new report "Plastic and Climate" was published. According to the report, in 2019, production and incineration of plastic will contribute greenhouse gases in the equivalent of 850 million tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) to the atmosphere. In current trend, annual emissions from these sources will grow to 1.34 billion tonnes by 2030. By 2050 plastic could emit 56 billion tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions, as much as 14 percent of the earth's remaining carbon budget.[72] By 2100 it will emit 260 billion tonnes, more than half of the carbon budget. Those are emission from production, transportation, incineration, but there are also releases of methane and effects on phytoplankton.[73]

Effects of plastic on land

[編集]Plastic pollution on land poses a threat to the plants and animals – including humans who are based on the land.[74] Estimates of the amount of plastic concentration on land are between four and twenty three times that of the ocean. The amount of plastic poised on the land is greater and more concentrated than that in the water.[75] Mismanaged plastic waste ranges from 60 percent in East Asia and Pacific to one percent in North America. The percentage of mismanaged plastic waste reaching the ocean annually and thus becoming plastic marine debris is between one third and one half the total mismanaged waste for that year.[76][77]

In 2021 a report conducted by the Food and Agriculture Organization stated that plastic is often used in agriculture. There is more plastic in the soil that in the oceans. The presence of plastic in the environment hurt ecosystems and human health and pose a threat to food safety.[78] Chlorinated plastic can release harmful chemicals into the surrounding soil, which can then seep into groundwater or other surrounding water sources and also the ecosystem of the world.[79] This can cause serious harm to the species that drink the water.

Effect on flooding

[編集]

Plastic waste can clog storm drains, and such clogging can increase flood damage, particularly in urban areas.[80] A buildup of plastic garbage at trash cans raises the water level upstream and may enhance the risk of urban flooding.[81] For example, in Bangkok flood risk increases substantially because of plastic waste clogging the already overburdened sewer system.[82]

In tap water

[編集]A 2017 study found that 83% of tap water samples taken around the world contained plastic pollutants.[83][84] This was the first study to focus on global drinking water pollution with plastics,[85] and showed that with a contamination rate of 94%, tap water in the United States was the most polluted, followed by Lebanon and India. European countries such as the United Kingdom, Germany and France had the lowest contamination rate, though still as high as 72%.[83] This means that people may be ingesting between 3,000 and 4,000 microparticles of plastic from tap water per year.[85] The analysis found particles of more than 2.5 microns in size, which is 2500 times bigger than a nanometer. It is currently unclear if this contamination is affecting human health, but if the water is also found to contain nano-particle pollutants, there could be adverse impacts on human well-being, according to scientists associated with the study.[86]

However, plastic tap water pollution remains under-studied, as are the links of how pollution transfers between humans, air, water, and soil.[87]

In terrestrial ecosystems

[編集]Mismanaged plastic waste leads to plastic directly or indirectly entering terrestrial ecosystems.[88] There has been a significant increase of microplastic pollution due to the poor handling and disposal of plastic materials.[89] In particular, plastic pollution in the form of microplastics now can be found extensively in soil. It enters the soil by settling on the surface and eventually making its way into subsoils.[90] These microplastics find their way into plants and animals.[91]

Effluent and sludge of wastewater contain large amounts of plastics. Wastewater treatment plants don't have a treatment process to remove microplastics which results in plastics being transferred into water and soil when effluent and sludge are applied to land for agricultural purposes.[91] Several researchers have found plastic microfibers that are released when fleece and other polyester textiles are cleaned in washing machines.[92] These fibers can be transferred through effluent to land which pollutes soil environments.[90]

The increase in plastic and microplastic pollution in soils can cause adverse impacts on plants and microorganisms in the soil, which can in turn affect soil fertility. Microplastics affect soil ecosystems that are important for plant growth. Plants are important for the environment and ecosystems so the plastics are damaging to plants and organisms living in these ecosystems.[89]

Microplastics alter soil biophysical properties which affect the quality of the soil. This affects soil biological activity, biodiversity and plant health. Microplastics in the soil alter a plant's growth. It decreases seedling germination, affects the number of leaves, stem diameter and chlorophyll content in these plants.[89]

Microplastics in the soil are a risk not only to soil biodiversity but also food safety and human health. Soil biodiversity is important for plant growth in agricultural industries. Agricultural activities such as plastic mulching and application of municipal wastes contribute to the microplastic pollution in the soil. Human-modified soils are commonly used to improve crop productivity but the effects are more damaging than helpful.[89]

Plastics also release toxic chemicals into the environment and cause physical, chemical harm and biological damage to organisms. Ingestion of plastic doesn't only lead to death in animals through intestinal blockage but it can also travel up the food chain which affects humans.[88]

Effects of plastic on oceans and seabirds

[編集]

Marine life is one of the most important when one is affected by plastic pollution. Plastic pollution puts animals' lives in danger and is in constant fear of extinction. Marine wildlife such as seabirds, whales, fish and turtles mistake plastic waste for prey; most then die of starvation as their stomachs become filled with plastic. They also suffer from lacerations, infections, reduced ability to swim, and internal injuries.[93] This evidence tells us how damaged marine wildlife is being affected by plastic pollution, they bring up how many animals mistake plastic for prey and eat it without knowing. "Globally, 100,000 marine mammals die every year as a result of plastic pollution. This includes whales, dolphins, porpoises, seals and sea lions".[94] This evidence tells us the statistics of how many marine mammals really are negatively affected enough to die from plastic pollution.

Effects on freshwater ecosystems

[編集]Research into freshwater plastic pollution has been largely ignored over marine ecosystems, comprising only 13% of published papers on the topic.[95]

Plastics make their way into bodies of freshwater, underground aquifers, and moving freshwaters through runoff and erosion of mismanaged plastic waste (MMPW). In some areas, the direct waste disposal into rivers is a remaining factor of historical practices, and has only been somewhat limited by modern legislation.[96] Rivers are the primary transport of plastics into marine ecosystems, sourcing potentially 80% of the plastic pollution in the oceans.[97] Research on the top ten river catchments ranked by annual amount of MMPW showed that some rivers contribute as high as 88–95% of ocean-bound plastics, the highest being the Yangtze River into the East China Sea.[98] Asian rivers contribute nearly 67% of plastic waste found in the ocean annually, largely influenced by the high density coastal populations all throughout the continent as well as relatively intense bouts of seasonal rainfall.[99]

Impacts on freshwater biodiversity

[編集]Invertebrates

[編集]A study analyzing ingestion of plastics across a variety of previously published experiments showed that out of the 206 species covered, the majority of papers documented ingestion in fish.[96] This doesn't quite mean that fish ingest plastic more than other organisms, but instead highlights the underrepresentation of plastic effects in equally important organisms, like aquatic plants, amphibians and invertebrates. Despite this disparity, controlled experiments analyzing microplastic impact on aquatic plants like the algae Chlorella spp and common duckweed Lemna minor have yielded significant results. Between microplastics of polypropylene (PP) and polyvinyl chloride (PVC), PVC demonstrated greater toxicity to Chlorella pyrenoidosa, overall negatively impacting their photosynthetic ability. This effect on photosynthesis is likely due to the 60% reduction of algal chlorophyll a associated with high PVC concentrations found in the same study.[100] When analyzing the effect of polyethylene microbeads (origin: cosmetic exfoliants) on the aquatic macrophyte L. minor, no effect on photosynthetic pigments & productivity was found, but root growth and root cell viability decreased.[101] These results are concerning as plants and algae are integral to nutrient and gas cycling within an aquatic system, and have the capacity to create significant changes in water composition due to their sheer density. Crustaceans have also been analyzed for their response to plastic presence. There is proof that freshwater crustaceans, specifically European crabs and crayfish, suffer entanglement in polyamide ghost nets used in lake fishing.[102] When exposed to plastic nanoparticles of polystyrene, Daphnia galeata (common water flea) experienced reduced survival within 48 hours as well as reproductive issues. Over a span of 5 days, the amount of pregnant Daphnia decreased by nearly 50%, and less than 20% of exposed embryos survived without any immediate repercussions.[103] Other arthropods, like juvenile stages of insects are susceptible to similar plastic exposure as some spend part of their adolescence fully submerged in a freshwater resource. This similarity in lifestyle to other aquatic invertebrates indicates that insects may experience similar side effects of plastic exposure.

Vertebrates

[編集]Plastic exposure in amphibians has mostly been studied in adolescent life stages, when the test subjects are still dependent on an aquatic environment where it can be easier to manipulate variables experimentally. Studies on a common South American freshwater frog, Physalaemus cuvieri indicated that plastics may have the potential to induce mutagenic and cytotoxic morphological changes.[104] Much more research needs to be done on amphibian response to plastic pollution, especially since amphibians can serve as initial indicator species of environmental decline.[105] Freshwater mammals and birds have long been known to have negative interactions with plastic pollution, often resulting in entanglement or suffocation/choking after ingesting. While inflammation within the gastrointestinal tract in both groups has been noted, unfortunately there is little to no data on the toxicological effects of plastic pollutants in these organisms.[96] Fish have been studied the most regarding plastic pollution in freshwater organisms, with the majority of studies indicating evidence of plastic ingestion in wild-caught samples and lab specimens.[96] There have been some attempts to look at lethality of plastics in a common freshwater model species, Danio rerio, aka zebrafish. Increased mucus production and inflammation response in the D. rerio GI-tract was noted, but additionally, researchers noted a distinct shift in the microbial communities within the zebrafish intestinal microbiome.[106] This finding is significant, as research within the last few decades has increasingly revealed how much power intestinal microbiomes have regarding their host's nutrient absorption and endocrine systems.[107] Because of this, plastics may have a far more drastic effect on individual organism health than is currently known so far, thus warranting the need for further research as soon as possible. Many of these findings also have been found in a laboratory setting, so more effort needs to be channeled into measuring plastic abundance & toxicology in wild populations.

Effects on humans

[編集]

Compounds that are used in manufacturing pollute the environment by releasing chemicals into the air and water. Some compounds that are used in plastics, such as phthalates, bisphenol A (BRA), polybrominated diphenyl ether (PBDE), are under close statute and might be very hurtful. Even though these compounds are unsafe, they have been used in the manufacturing of food packaging, medical devices, flooring materials, bottles, perfumes, cosmetics and much more. Inhalation of microplastics (MPs) have been shown to be one of the major contributors to MP uptake in humans. MPs in the form of dust particles are circulated constantly through ventilation and air conditioning systems indoors.[108] The large dosage of these compounds are hazardous to humans, destroying the endocrine system. BRA imitates the female's hormone called estrogen. PBD destroys and causes damage to thyroid hormones, which are vital hormone glands that play a major role in the metabolism, growth and development of the human body. MPs can also have a detrimental effect on male reproductive success. MPs such as BPA can interfere with steroid biosynthesis in the male endocrine system and with early stages of spermatogenesis.[109] MPs in men can also create oxidative stress and DNA damage in spermatozoa, causing reduced sperm viability.[109] Although the level of exposure to these chemicals varies depending on age and geography, most humans experience simultaneous exposure to many of these chemicals. Average levels of daily exposure are below the levels deemed to be unsafe, but more research needs to be done on the effects of low dose exposure on humans. A lot is unknown on how severely humans are physically affected by these chemicals. Some of the chemicals used in plastic production can cause dermatitis upon contact with human skin. In many plastics, these toxic chemicals are only used in trace amounts, but significant testing is often required to ensure that the toxic elements are contained within the plastic by inert material or polymer. Children and women during their reproduction age are at most at risk and more prone to damaging their immune as well as their reproductive system from these hormone-disrupting chemicals. Pregnancy and nursing products such as baby bottles, pacifiers, and plastic feeding utensils place infants and children at a very high risk of exposure.[108]

Human health has also been negatively impacted by plastic pollution. "Almost a third of groundwater sites in the US contain BPA. BPA is harmful at very low concentrations as it interferes with our hormone and reproductive systems.[110] This quote tells us how much of a percentage of our water is contaminated and should not be drunk on a daily basis. "At every stage of its lifecycle, plastic poses distinct risks to human health, arising from both exposure to plastic particles themselves and associated chemicals".[111] This quote is an intro to numerous points of why plastic is damaging to us, such as the carbon that is released when it is being made and transported which is also related to how plastic pollution harms our environment.

A 2022 study published in Environment International found microplastic in the blood of 80% of people tested in the study, and such microplastic has the potential to become embedded in human organs.[112]

Clinical significance

[編集]Due to the pervasiveness of plastic products, most of the human population is constantly exposed to the chemical components of plastics. In the United States, 95% of adults have had detectable levels of BPA in their urine. Exposure to chemicals such as BPA have been correlated with disruptions in fertility, reproduction, sexual maturation, and other health effects.[113] Specific phthalates have also resulted in similar biological effects.

Thyroid hormone axis

[編集]Bisphenol A affects gene expression related to the thyroid hormone axis, which affects biological functions such as metabolism and development. BPA can decrease thyroid hormone receptor (TR) activity by increasing TR transcriptional corepressor activity. This then decreases the level of thyroid hormone binding proteins that bind to triiodothyronine. By affecting the thyroid hormone axis, BPA exposure can lead to hypothyroidism.[13]

Sex hormones

[編集]BPA can disrupt normal, physiological levels of sex hormones. It does this by binding to globulins that normally bind to sex hormones such as androgens and estrogens, leading to the disruption of the balance between the two. BPA can also affect the metabolism or the catabolism of sex hormones. It often acts as an antiandrogen or as an estrogen, which can cause disruptions in gonadal development and sperm production.[13]

Reduction efforts

[編集]

Efforts to reduce the use of plastics, to promote plastic recycling and to reduce mismanaged plastic waste or plastic pollution have occurred or are ongoing. The first scientific review in the professional academic literature about global plastic pollution in general found that the rational response to the "global threat" would be "reductions in consumption of virgin plastic materials, along with internationally coordinated strategies for waste management" – such as banning export of plastic waste unless it leads to better recycling – and describes the state of knowledge about "poorly reversible" impacts which are one of the rationales for its reduction.[114][115]

Some supermarkets charge their customers for plastic bags, and in some places more efficient reusable or biodegradable materials are being used in place of plastics. Some communities and businesses have put a ban on some commonly used plastic items, such as bottled water and plastic bags.[116] Some non-governmental organizations have launched voluntary plastic reduction schemes like certificates that can be adapted by restaurants to be recognized as eco-friendly among customers.[117]

In January 2019 a "Global Alliance to End Plastic Waste" was created by companies in the plastics industry. The alliance aims to clean the environment from existing waste and increase recycling, but it does not mention reduction in plastic production as one of its targets.[118]

On 2 March 2022 in Nairobi, representatives of 175 countries pledged to create a legally binding agreement to end plastic pollution. The agreement should address the full lifecycle of plastic and propose alternatives including reusability. An Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) that should conceive the agreement by the end of the year 2024 was created. The agreement should facilitate the transition to a circular economy, which will reduce GHG emissions by 25%. Inger Andersen, executive director of UNEP called the decision "a triumph by planet earth over single-use plastics".[21][119]

Biodegradable and degradable plastics

[編集]The use of biodegradable plastics has many advantages and disadvantages. Biodegradables are biopolymers that degrade in industrial composters. Biodegradables do not degrade as efficiently in domestic composters, and during this slower process, methane gas may be emitted.[120]

There are also other types of degradable materials that are not considered to be biopolymers, because they are oil-based, similar to other conventional plastics. These plastics are made to be more degradable through the use of different additives, which help them degrade when exposed to UV rays or other physical stressors.[120] yet, biodegradation-promoting additives for polymers have been shown not to significantly increase biodegradation.[121]

Although biodegradable and degradable plastics have helped reduce plastic pollution, there are some drawbacks. One issue concerning both types of plastics is that they do not break down very efficiently in natural environments. There, degradable plastics that are oil-based may break down into smaller fractions, at which point they do not degrade further.[120]

A parliamentary committee in the United Kingdom also found that compostable and biodegradable plastics could add to marine pollution because there is a lack of infrastructure to deal with these new types of plastic, as well as a lack of understanding about them on the part of consumers.[122] For example, these plastics need to be sent to industrial composting facilities to degrade properly, but no adequate system exists to make sure waste reaches these facilities.[122] The committee thus recommended to reduce the amount of plastic used rather than introducing new types of it to the market.[122]

Also worth noting is the evolution of new enzymes allowing microorganisms living in polluted locations to digest normal, hard-to-degrade plastic. An 2021 study looking for homologs of 95 known plastic-degrading enzymes spanning 17 plastic types found a further 30,000 possible enzymes. Despite their apparent ubiquity, there is no current evidence that these novel enzymes are breaking down any meaningful amount of plastic to reduce pollution.[123]

Incineration

[編集]Up to 60% of used plastic medical equipment is incinerated rather than deposited in a landfill as a precautionary measure to lessen the transmission of disease. This has allowed for a large decrease in the amount of plastic waste that stems from medical equipment.[113]

At a large scale, plastics, paper, and other materials provides waste-to-energy plants with useful fuel. About 12% of total produced plastic has been incinerated.[124] Many studies have been done concerning the gaseous emissions that result from the incineration process.[125] Incinerated plastics release a number of toxins in the burning process, including Dioxins, Furans, Mercury and Polychlorinated Biphenyls.[125] When burned outside of facilities designed to collect or process the toxins, this can have significant health effects and create significant air pollution.[125]

Policy

[編集]

Agencies such as the US Environmental Protection Agency and US Food and Drug Administration often do not assess the safety of new chemicals until after a negative side effect is shown. Once they suspect a chemical may be toxic, it is studied to determine the human reference dose, which is determined to be the lowest observable adverse effect level. During these studies, a high dose is tested to see if it causes any adverse health effects, and if it does not, lower doses are considered to be safe as well. This does not take into account the fact that with some chemicals found in plastics, such as BPA, lower doses can have a discernible effect.[126] Even with this often complex evaluation process, policies have been put into place in order to help alleviate plastic pollution and its effects. Government regulations have been implemented that ban some chemicals from being used in specific plastic products.

In Canada, the United States, and the European Union, BPA has been banned from being incorporated in the production of baby bottles and children's cups, due to health concerns and the higher vulnerability of younger children to the effects of BPA.[113] Taxes have been established in order to discourage specific ways of managing plastic waste. The landfill tax, for example, creates an incentive to choose to recycle plastics rather than contain them in landfills, by making the latter more expensive.[120] There has also been a standardization of the types of plastics that can be considered compostable.[120] The European Norm EN 13432, which was set by the European Committee for Standardization (CEN), lists the standards that plastics must meet, in terms of compostability and biodegradability, in order to officially be labeled as compostable.[120][127]

Given the significant threat that oceans face, the European Investment Bank Group aims to increase its funding and advisory assistance for ocean cleanup. For example, the Clean Oceans Initiative (COI) was established in 2018. The European Investment Bank, the German Development Bank, and the French Development Agency (AFD) agreed to invest a total of €2 billion under the COI from October 2018 to October 2023 in initiatives aimed at reducing pollution discharge into the oceans, with a special focus on plastics.[128][129][130]

Voluntary reduction efforts failing

[編集]Major plastic producers continue to lobby governments to refrain from imposing restrictions on plastic production and to advocate for voluntary corporate targets to reduce new plastic output. However, the world's top 10 plastic producers, including The Coca-Cola Company, Nestle SA and PepsiCo have been failing to meet even their own minimum targets for virgin plastic use.[131]

There have been several international covenants which address marine plastic pollution, such as the Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter 1972, the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, 1973 and the Honolulu Strategy, there is nothing around plastics which infiltrate the ocean from the land.[132]

In 2020, 180 countries agreed to limit the amount of plastic waste that rich countries export to poorer countries, using rules from the Basel Convention. However, during January 2021, the first month that the agreement was in effect, trade data showed that overall scrap exports actually increased.[133]

Legally binding plastics treaty

[編集]Some academics and NGOs believe that a legally binding international treaty to deal with plastic pollution is necessary. They think this because plastic pollution is an international problem, moving between maritime borders, and also because they believe there needs to be a cap on plastic production.[134][135][136] Lobbyists were hoping that UNEA-5 would lead to a plastics treaty, but the session ended without a legally binding agreement.[137][138]

In 2022, countries agreed to devise a Global plastic pollution treaty by 2024.[139][140]

Waste import bans

[編集]Since around 2017, China,[141] Turkey,[142] Malaysia,[143] Cambodia,[144] and Thailand[145] have banned certain waste imports. It has been suggested that such bans may increase automation[146] and recycling, decreasing negative impacts on the environment.[147]

According to an analysis of global trade data by the nonprofit Basel Action Network, violations of the Basel Convention, active since January 1, 2021, have been rampant during 2021. The U.S., Canada, and the European Union have sent hundreds of millions of tons of plastic to countries with insufficient waste management infrastructure, where much of it is landfilled, burned, or littered into the environment.[148]

Circular economy policies

[編集]Laws related to recyclability, waste management, domestic materials recovery facilities, product composition, biodegradability and prevention of import/export of specific wastes may support prevention of plastic pollution.[要出典] A study considers producer/manufacturer responsibility "a practical approach toward addressing the issue of plastic pollution", suggesting that "Existing and adopted policies, legislations, regulations, and initiatives at global, regional, and national level play a vital role".[71]

Standardization of products, especially of packaging[149][150]Template:Additional citation needed which are, as of 2022, often composed of different materials (each and across products) that are hard or currently impossible to either separate or recycle together in general or in an automated way[151][152] could support recyclability and recycling.

For instance, there are systems that can theoretically distinguish between and sort 12 types of plastics such as PET using hyperspectral imaging and algorithms developed via machine learning[153][154] while only an estimated 9% of the estimated 6.3 billion tonnes of plastic waste from the 1950s up to 2018 has been recycled (12% has been incinerated and the rest reportedly being "dumped in landfills or the natural environment").[11]

Collection, recycling and reduction

[編集]The two common forms of waste collection include curbside collection and the use of drop-off recycling centers. About 87 percent of the population in the United States (273 million people) have access to curbside and drop-off recycling centers. In curbside collection, which is available to about 63 percent of the United States population (193 million people), people place designated plastics in a special bin to be picked up by a public or private hauling company.[155] Most curbside programs collect more than one type of plastic resin, usually both PETE and HDPE.[156] At drop-off recycling centers, which are available to 68 percent of the United States population (213 million people), people take their recyclables to a centrally located facility.[155] Once collected, the plastics are delivered to a materials recovery facility (MRF) or handler for sorting into single-resin streams to increase product value. The sorted plastics are then baled to reduce shipping costs to reclaimers.[156]

There are varying rates of recycling per type of plastic, and in 2017, the overall plastic recycling rate was approximately 8.4% in the United States. Approximately 2.7 millionメトリックトン (3.0 millionショートトン) of plastics were recycled in the U.S. in 2017, while 24.3 millionメトリックトン (26.8 millionショートトン) plastic were dumped in landfills the same year. Some plastics are recycled more than others; in 2017 about 31.2 percent of HDPE bottles and 29.1 percent of PET bottles and jars were recycled.[157]

Reusable packaging refers to packaging that is manufactured of durable materials and is specifically designed for multiple trips and extended life. There are zero-waste stores and refill shops[158][159] for selected products as well as conventional supermarkets that enable refilling of selected plastics-packaged products or voluntarily sell products with no or more sustainable packaging.[160]

On 21 May 2019, a new service model called "Loop" to collect packaging from consumers and reuse it, began to function in the New York region, US, supported by multiple larger companies. Consumers drop packages in special shipping totes and then a pick up collect, clean, refill and return them.[161] It has begun with several thousand households and aims to not only stop single use plastic, but to stop single use generally by recycling consumer product containers of various materials.[162]

Another effective strategy, that could be supported by policies, is eliminating the need for plastic bottles such as by using refillable e.g. steel bottles,[163] and water carbonators,[164]Template:Additional citation needed which may also prevent potential negative impacts on human health due to microplastics release.[165][166][167]

Reducing plastic waste could support recycling and is often taken together with recycling: the "3R" refer to Reduce, Reuse and Recycle.[71][168][169][170]

Ocean cleanup

[編集]The organization "The Ocean Cleanup" is trying to collect plastic waste from the oceans by nets. There are concerns from harm to some forms of sea organisms, especially neuston.[171]

Great Bubble Barrier

[編集]In the Netherlands, plastic litter from some rivers is collected by a bubble barrier, to prevent plastics from floating into the sea. This so-called 'Great Bubble Barrier’ catches plastics bigger than 1 mm.[172][24] The bubble barrier is implemented in the River IJssel (2017) and in Amsterdam (2019)[173][174] and will be implemented in Katwijk at the end of the river Rhine.[175][176]

Mapping and tracking

[編集]Our World In Data provides graphics about some analyses, including maps, to show sources of plastic pollution[177][178] – including that of oceans in specific.[179]

Identifying largest sources of ocean plastics in high fidelity may help to discern causes, to measure progress and to develop effective countermeasures.

A large fraction of ocean plastics may come from – also non-imported Template:See above – plastic waste of coastal cities[177] as well as from rivers (with top 1000 rivers estimated by one 2021 study to account for 80% of global annual emissions).[180] These two sources may be interlinked.[181] The Yangtze river into the East China Sea is identified by some studies that use sampling evidence as the highest plastic-emitting (sampled) river,[98][182] in contrast to the beforementioned 2021 study that ranks it at place 64.[180] Management interventions at the local level at coastal areas were found to be crucial to the global success of reducing plastic pollution.[183]

There is one global, interactive machine learning- and satellite monitoring-based, map of plastic waste sites which could help identify who and where mismanages plastic waste, dumping it into oceans.[184][185]

By country/region

[編集]Albania

[編集]In July 2018, Albania became the first country in Europe to ban lightweight plastic bags.[186][187][188] Albania's environment minister Blendi Klosi said that businesses importing, producing or trading plastic bags less than 35 microns in thickness risk facing fines between 1 million to 1.5 million lek (€7,900 to €11,800).[187]

Australia

[編集]It has been estimated that each year, Australia produces around 2.5m tonnes of plastic waste annually, of which about 84% ends up as landfill, and around 130,000 tonnes of plastic waste leaks into the environment.[189] Six of the eight states and territories had by December 2021 committed to banning a range of plastics. The federal government's National Packaging Targets created the goal of phasing out the worst of single-use plastics by 2025,[190] and under the National Plastics Plan 2021,[191] it has committed "to phase out loose fill and moulded polystyrene packaging by July 2022, and various other products by December 2022.[190]

Canada

[編集]In the year 2022 Canada announced a ban on producing and importing single use plastic from December 2022. The sale of those items will be banned from December 2023 and the export from 2025. The prime minister of Canada Justin Trudeau pledged to ban single use plastic in 2019.[192]

China

[編集]China is the biggest consumer of single-use plastics.[53] In 2020 China published a plan to cut 30% of plastic waste in 5 years. As part of this plan, single use plastic bags and straws will be banned[193][194]

European Union

[編集]In 2015 the European Union adopted a directive requiring a reduction in the consumption of single use plastic bags per person to 90 by 2019 and to 40 by 2025.[195] In April 2019, the EU adopted a further directive banning almost all types of single use plastic, except bottles, from the beginning of the year 2021.[196][197]

On 3 July 2021, the EU Single-Use Plastics Directive (SUPD, EU 2019/904) went into effect in EU member states. The directive aims to reduce plastic pollution from single-use disposable plastics. It focuses on the 10 most commonly found disposable plastics at beaches, which make up 43% of marine litter (fishing gear another 27%). According to the SUP directive, there is a ban on: plastic cotton buds and balloon sticks; plastic plates, cutlery, stirrers and straws; Styrofoam drinks and food packaging (f.e. disposable cups, one-person meals); products made of oxo-degradable plastics, which degrade into microplastics. cigarette filters, drinking cups, wet wipes, sanitary towels and tampons receive a label indicating the product contains plastic, that it belongs in the trash, and that litter has negative effects on the environment.[198][199]

India[edit source]

[編集]Say no to polythene. Sign. Nako, Himachal Pradesh, India. The government of India decided to ban single use plastics and take a number of measures to recycle and reuse plastic, from 2 October 2019

The Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation, Government of India, has requested various governmental departments to avoid the use of plastic bottles to provide drinking water during governmental meetings, etc., and to instead make arrangements for providing drinking water that do not generate plastic waste. The state of Sikkim has restricted the usage of plastic water bottles (in government functions and meetings) and styrofoam products. The state of Bihar has banned the usage of plastic water bottles in governmental meetings.

The 2015 National Games of India, organised in Thiruvananthapuram, was associated with green protocols. This was initiated by Suchitwa Mission that aimed for "zero-waste" venues. To make the event "disposable-free", there was ban on the usage of disposable water bottles. The event witnessed the usage of reusable tableware and stainless steel tumblers. Athletes were provided with refillable steel flasks. It is estimated that these green practices stopped the generation of 120 tonnes of disposable waste.

The city of Bangalore in 2016 banned the plastic for all purpose other than for few special cases like milk delivery etc.

The state of Maharashtra, India effected the Maharashtra Plastic and Thermocol Products ban 23 June 2018, subjecting plastic users to fines and potential imprisonment for repeat offenders.

In the year 2022 India has begun to implement a country wide ban on different sorts of plastic. This is necessary also for achieving the climate targets of the country as in plastic production are used more than 8,000 additives, part of them are thousands times more powerful greenhouse gases than CO2.

Indonesia

[編集]In Bali, one of the many islands of Indonesia, two sisters, Melati and Isabel Wijsen, made efforts to ban plastic bags in 2019.[200][201] January 2022年現在[update] their organization Bye Bye Plastic Bags had spread to over 50 locations around the world.[202]

Israel

[編集]In Israel, two cities: Eilat and Herzliya, decided to ban the usage of single use plastic bags and cutlery on the beaches.[203] In 2020 Tel Aviv joined them, banning also the sale of single use plastic on the beaches.[204]

Kenya

[編集]In August 2017, Kenya has one of the world's harshest plastic bag bans. Fines of $38,000 or up to four years in jail to anyone that was caught producing, selling, or using a plastic bag.[205]

New Zealand

[編集]New Zealand announced a ban on many types of hard-to-recycle single use plastic by 2025.[206]

Nigeria

[編集]In 2019, The House of Representatives of Nigeria banned the production, import and usage of plastic bags in the country.[207]

Taiwan

[編集]In February 2018, Taiwan restricted the use of single-use plastic cups, straws, utensils and bags; the ban will also include an extra charge for plastic bags and updates their recycling regulations and aiming by 2030 it would be completely enforced.[205]

United Kingdom

[編集]In January 2019, the Iceland supermarket chain, which specializes in frozen foods, pledged to "eliminate or drastically reduce all plastic packaging for its store-brand products by 2023."[208]

As of 2020, 104 communities achieved the title of "Plastic free community" in United Kingdom, 500 want to achieve it.[209]

After two schoolgirls Ella and Caitlin launched a petition about it, Burger King and McDonald's in the United Kingdom and Ireland pledged to stop sending plastic toys with their meals. McDonald's pledged to do it from the year 2021. McDonald's also pledged to use a paper wrap for it meals and books that will be sent with the meals. The transmission will begin already in March 2020.[210]

United States

[編集]In 2009, Washington University in St. Louis became the first university in the United States to ban the sale of plastic, single-use water bottles.[211]

In 2009, the District of Columbia required all businesses that sell food or alcohol to charge an additional 5 cents for each carryout plastic or paper bag.[212]

In 2011 and 2013, Kauai, Maui and Hawaii prohibit non-biodegradable plastic bags at checkout as well as paper bags containing less than 40 percent recycled material. In 2015, Honolulu was the last major county approving the ban.[212]

In 2015, California prohibited large stores from providing plastic bags, and if so a charge of $0.10 per bag and has to meet certain criteria.[212]

In 2016, Illinois adopted the legislation and established “Recycle Thin Film Friday” in effort toe reclaim used thin-film plastic bags and encourage reusable bags.[212]

In 2019, the state New York banned single use plastic bags and introduced a 5-cent fee for using single use paper bags. The ban will enter into force in 2020. This will not only reduce plastic bag usage in New York state (23 billion every year until now), but also eliminate 12 million barrels of oil used to make plastic bags used by the state each year.[213][214]

The state of Maine ban Styrofoam (polystyrene) containers in May 2019.[215]

In 2019 the Giant Eagle retailer became the first big US retailer that committed to completely phase out plastic by 2025. The first step – stop using single use plastic bags – will begun to be implemented already on January 15, 2020.[216]

In 2019, Delaware, Maine, Oregon and Vermont enacted on legislation. Vermont also restricted single-use straws and polystyrene containers.[212]

In 2019, Connecticut imposed a $0.10 charge on single-use plastic bags at point of sale, and is going to ban them on July 1, 2021.[212]

Vanuatu

[編集]On July 30, 2017, Vanuatu's Independence Day, made an announcement of stepping towards the beginning of not using plastic bags and bottles. Making it one of the first Pacific nations to do so and will start banning the importation of single-use plastic bottles and bags.[205]

Obstruction by major plastic producers

[編集]The ten corporations that produce the most plastic on the planet, The Coca-Cola Company, Colgate-Palmolive, Danone, Mars, Incorporated, Mondelēz International, Nestlé, PepsiCo, Perfetti Van Melle, Procter & Gamble, and Unilever, formed a well-financed network that has sabotaged for decades government and community efforts to address the plastic pollution crisis, according to a detailed investigative report by the Changing Markets Foundation. The investigation documents how these companies delay and derail legislation so that they can continue to inundate consumers with disposable plastic packaging. These large plastic producers have exploited public fears of the COVID-19 pandemic to work toward delaying and reversing existing regulation of plastic disposal. Big ten plastic producers have advanced voluntary commitments for plastic waste disposal as a stratagem to deter governments from imposing additional regulations.[217]

Deception of the public about recycling

[編集]As early as the early 1970s, petrochemical industry leaders understood that the vast majority of plastic they produced would never be recycled. For example, an April 1973 report written by industry scientists for industry executive states that sorting the hundreds of different kinds plastic is "infeasible" and cost-prohibitive. By the late 1980s, industry leaders also knew that the public must be kept feeling good about purchasing plastic products if their industry was to continue to prosper, and needed to quell proposed legislation to regulate the plastic being sold. So the industry launched a $50 million/year corporate propaganda campaign targeting the American public with the message that plastic can be, and is being, recycled, and lobbied American municipalities to launch expensive plastic waste collection programs, and lobbied U.S. states to require the labeling of plastic products and containers with recycling symbols. They were confident, however, that the recycling initiatives would not end up recovering and reusing plastic in amounts anywhere near sufficient to hurt their profits in selling new "virgin" plastic products because they understood that the recycling efforts that they were promoting were likely to fail. Industry leaders more recently have planned 100% recycling of the plastic they produce by 2040, calling for more efficient collection, sorting and processing.[218][219]

Action for creating awareness

[編集]Earth Day

[編集]In 2019, the Earth Day Network partnered with Keep America Beautiful and National Cleanup Day for the inaugural nationwide Earth Day CleanUp. Cleanups were held in all 50 states, five US territories, 5,300 sites and had more than 500,000 volunteers.[220][221]

Earth Day 2020 is the 50th Anniversary of Earth Day. Celebrations will include activities such as the Great Global CleanUp, Citizen Science, Advocacy, Education, and art. This Earth Day aims to educate and mobilize more than one billion people to grow and support the next generation of environmental activists, with a major focus on plastic waste[222][223]

World Environment Day

[編集]Every year, 5 June is observed as World Environment Day to raise awareness and increase government action on the pressing issue. In 2018, India was host to the 43rd World Environment Day and the theme was "Beat Plastic Pollution", with a focus on single-use or disposable plastic. The Ministry of Environment, Forest, and Climate Change of India invited people to take care of their social responsibility and urged them to take up green good deeds in everyday life. Several states presented plans to ban plastic or drastically reduce their use.[224]

Other actions

[編集]On 11 April 2013 in order to create awareness, artist Maria Cristina Finucci founded The Garbage Patch State at UNESCO[225] headquarters in Paris, France, in front of Director General Irina Bokova. This was the first of a series of events under the patronage of UNESCO and of the Italian Ministry of the Environment.[226]

See also

[編集]- Eddy pumping – The role of mesoscale eddies in trapping and transporting plastic in the ocean

- Great Pacific garbage patch – an area with concentrations of pelagic plastics, chemical sludge, and other debris

- Plastic-eating organisms

- Marine plastic pollution

- Plasticulture

- Refill (scheme)

- Reverse vending machine

- Rubber pollution

Notes

[編集]- ^ "Campaigners have identified the global trade in plastic waste as a main culprit in marine litter, because the industrialised world has for years been shipping much of its plastic “recyclables” to developing countries, which often lack the capacity to process all the material."[33]

- ^ "The new UN rules will effectively prevent the US and EU from exporting any mixed plastic waste, as well plastics that are contaminated or unrecyclable – a move that will slash the global plastic waste trade when it comes into effect in January 2021."[33]

References

[編集]- ^ a b "Plastic pollution". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2013年8月1日閲覧。

- ^ a b Laura Parker (June 2018). “We Depend on Plastic. Now We're Drowning in It.”. NationalGeographic.com. 25 June 2018閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Hammer, J; Kraak, MH; Parsons, JR (2012). “Plastics in the marine environment: the dark side of a modern gift”. Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 220: 1–44. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-3414-6_1. ISBN 978-1461434139. PMID 22610295.

- ^ a b Hester, Ronald E. (2011) (英語). Marine Pollution and Human Health. Royal Society of Chemistry. ISBN 978-1-84973-240-6

- ^ a b c d e f “When The Mermaids Cry: The Great Plastic Tide”. Coastal Care (March 2018). 5 April 2018時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。10 November 2018閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f Jambeck, Jenna R.; Geyer, Roland; Wilcox, Chris; Siegler, Theodore R.; Perryman, Miriam; Andrady, Anthony; Narayan, Ramani; Law, Kara Lavender (2015-02-13). “Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean” (英語). Science 347 (6223): 768–771. Bibcode: 2015Sci...347..768J. doi:10.1126/science.1260352. PMID 25678662.

- ^ Jang, Yong Chang; Lee, Jongmyoung; Hong, Sunwook; Choi, Hyun Woo; Shim, Won Joon; Hong, Su Yeon (2015-11). “Estimating the Global Inflow and Stock of Plastic Marine Debris Using Material Flow Analysis :a Preliminary Approach” (朝鮮語). 한국해양환경·에너지학회지 18 (4): 263–273. doi:10.7846/jkosmee.2015.18.4.263.

- ^ a b Sutter, John D. (12 December 2016). “How to stop the sixth mass extinction”. CNN. 18 September 2017閲覧。

- ^ Jang, Y. C., Lee, J., Hong, S., Choi, H. W., Shim, W. J., & Hong, S. Y. 2015. "Estimating the global inflow and stock of plastic marine debris using material flow analysis: a preliminary approach". Journal of the Korean Society for Marine Environment and Energy, 18(4), 263–273.[1]

- ^ a b “Archived copy”. 1 September 2021時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。6 October 2021閲覧。

- ^ a b c “The known unknowns of plastic pollution”. The Economist. (3 March 2018) 17 June 2018閲覧。

- ^ a b Nomadic, Global (29 February 2016). “Turning rubbish into money – environmental innovation leads the way”. 2022年8月21日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d Mathieu-Denoncourt, Justine; Wallace, Sarah J.; de Solla, Shane R.; Langlois, Valerie S. (November 2014). “Plasticizer endocrine disruption: Highlighting developmental and reproductive effects in mammals and non-mammalian aquatic species”. General and Comparative Endocrinology 219: 74–88. doi:10.1016/j.ygcen.2014.11.003. PMID 25448254.

- ^ a b Walker, Tony R.; Xanthos, Dirk (2018). “A call for Canada to move toward zero plastic waste by reducing and recycling single-use plastics”. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 133: 99–100. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2018.02.014.

- ^ a b “Picking up litter: Pointless exercise or powerful tool in the battle to beat plastic pollution?”. unenvironment.org (18 May 2018). 19 July 2019閲覧。

- ^ a b Laville, Sandra (December 9, 2020). “Human-made materials now outweigh Earth's entire biomass – study”. The Guardian December 9, 2020閲覧。

- ^ a b c “U.S. generates more plastic trash than any other nation, report finds” (英語). Environment (2020年10月30日). 2022年8月21日閲覧。

- ^ a b “Governments agree landmark decisions to protect people and planet from hazardous chemicals and waste, including plastic waste” (英語). UN Environment (2019年5月12日). 2022年8月21日閲覧。

- ^ a b “Nearly all countries agree to stem flow of plastic waste into poor nations” (英語). the Guardian (2019年5月10日). 2022年8月21日閲覧。

- ^ a b “180 nations agree UN deal to regulate export of plastic waste” (英語). phys.org. 2022年8月21日閲覧。

- ^ a b c “Historic day in the campaign to beat plastic pollution: Nations commit to develop a legally binding agreement”. UN Environment Programme (UNEP) (2 March 2022). 11 March 2022閲覧。

- ^ a b Shams, Mehnaz; Alam, Iftaykhairul; Mahbub, Md Shahriar (October 2021). “Plastic pollution during COVID-19: Plastic waste directives and its long-term impact on the environment”. Environmental Advances 5: 100119. doi:10.1016/j.envadv.2021.100119. ISSN 2666-7657. PMC 8464355. PMID 34604829.

- ^ a b Ana, Silva (2021). “Increased Plastic Pollution Due to Covid-19 Pandemic: Challenges and Recommendations.”. Chemical Engineering Journal 405: 126683. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2020.126683. PMC 7430241. PMID 32834764.

- ^ a b c “The Great Bubble Barrier: How bubbles are keeping plastic out of the sea”. euronews.com. Euronews.green (22 September 2021). November 26, 2021閲覧。

- ^ a b “Plastics industry adapts to business during COVID-19” (英語). Plastics News (2020年3月13日). 2021年12月18日閲覧。

- ^ a b “Plastic in the time of a pandemic: protector or polluter?” (英語). World Economic Forum. 2021年12月18日閲覧。

- ^ a b Monella, Lillo Montalto (2020年5月12日). “Will plastic pollution get worse after the COVID-19 pandemic?” (英語). euronews. 2021年12月18日閲覧。

- ^ a b Westervelt, Amy (2020年1月14日). “Big Oil Bets Big on Plastic” (英語). Drilled News. 2021年12月18日閲覧。

- ^ a b The world without us. New York: Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin's Press. (2007). ISBN 978-1443400084

- ^ a b “Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made”. Science Advances 3 (7): e1700782. (July 2017). Bibcode: 2017SciA....3E0782G. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1700782. PMC 5517107. PMID 28776036.