利用者:Sarandora/試訳中記事1

| {{{人名}}} | |

|---|---|

| |

| 在位 | 1529年7月26日 - 1541年6月26日 |

| 在位 | 1529年7月26日 - 1541年6月26日 |

| 出生 |

諸説有(1471年説、1476年説) |

| 死去 |

1541年6月26日(満65歳没或いは70歳没) |

| 王朝 | ピサロ家 |

| 父親 |

ゴンサロ・ピサロ・ロドリゲス・デ・アギラール Gonzalo Pizarro Rodríguez de Aguilar |

| 母親 |

フランシスカ・ゴンザレス・マテオス Francisca González Mateos |

フランシスコ・ピサロ・ゴンザレス (Francisco Pizarro González 1471年或いは1476年 - 1541年6月26日)はイベリア半島の南西部に位置するエストラマドゥーラ地方の小村トルヒーリョ出身の貴族、軍人、政治家。いわゆるコンキスタドール(南米の植民地化を主導した探検家、冒険家、征服者)の一人として、現在のペルー地方などを征服した事で知られている。また同じコンキスタドールのエルナン・コルテスは親族にあたる。

略歴

[編集]カスティーリャ王冠領に領地を持つ小貴族の息子として生まれる。母は父の召使であり、妾の子として私生児の身分であった事から貴族の子弟としての教育を与えて貰えず[1]、母の元で貧しい生活を送っていた。アロンソ・デ・オヘーダ卿の新大陸航海に加わった事を契機に探検家の道を選び、やがて同郷の冒険者バスコ・ヌーニェス・デ・バルボアの部下として太平洋航海を経て南米到達に成功した[1]。バルボアとその一団は故国で栄誉を受けるが、中南米探検で次第にバルボアが本国の反感を買い始める。ピサロは本国から派遣された監督役のペドロ・アリアス・デ・アビラと手を結び、バルボアを暗殺した。この功績によって占領地にカスティーリャ・デ・オロ総督領(後のパナマ総督領)が設置され、総督になったアリアス・デ・アビラからパナマ行政官の地位を与えられた。

1524年、中南米に存在する原住民勢力の中でも大国であったアステカ帝国をエルナン・コルテスが滅ぼし、またその際に膨大な金銀財宝を獲得したとの噂が広まる。自らもバルボアやコルテスの様に独立したコンキスタドールとしての大きな成功を望んでいたピサロは軍と資金を集め、別の原住民による国家であるインカ帝国の領域に侵入した。しかし最初の遠征は悪路や天候に阻まれて思う様に進まず、1526年の第二次遠征も不調に終った。後任のパナマ総督ペドロ・デ・リオスからは遠征を断念する様に説得され、ピサロが提案を拒絶すると三度目の遠征については総督領からの援助を拒否された。

遠征再開を望むピサロは総督達の上に立つ国王への直談判を決意、神聖ローマ皇帝及びカスティーリャ王カルロス5世に謁見を許され、三度目の遠征支援を嘆願した。カルロス5世はピサロの願いを聞き入れ、遠征についての許可証と資金援助を与えた。更には占領地の管理についてもピサロの裁量に任せるという布告まで与えられ、占領地に設置する事となったヌエバ・カスティーリャ総督領の総督に任命された。一族や友人から志願者を募ると再び中南米へと帰還した。

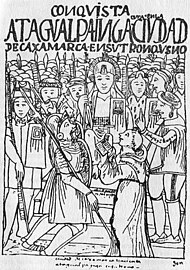

三度目の遠征でペルー沿岸部に上陸したピサロの軍勢は抵抗の激しい沿岸部を通り抜け、海岸から少し離れた場所に最初の入植地サン・ミゲル・デ・ピウラを建設した。程なくインカ皇帝アタワルパは異国人の入植は許可できないと通告し、ピサロはインカ帝国側との交渉の場に向かったが、同時に戦いの準備も行わせた。1532年11月16日、ピサロとアタワルパの会見が決裂すると戦いが始まり、約200名のピサロ軍は油断していた数千名のインカ兵を壊滅に追い込んだ(カハマルカの戦い)。アタワルパも玉座から引き摺り下ろして捕らえ、賠償金として王家の財宝を差し出させ、更にキリスト教に改宗させた上で絞首刑にした。決戦での勝利で勢いを得たピサロは進軍を続け、1535年にペルー地方全域を占領すると入植地の中核となる都市としてリマ市を建都した。

その後もペルー地方の実質的な支配者として君臨したが、1541年6月26日に粛清した臣下の息子によって暗殺された。遺骸は彼が作り上げたリマ市の大聖堂に葬られ、現在も同地に埋葬されている。ヌエバ・カスティーリャ総督領はペルー副王領に再編され、現在のペルー共和国の直接的な起源となった。

ピサロについては他のコンキスタドールと同様に現代的な価値観から批判される植民地支配の実行者として否定的に評価される傾向にある。軍事的な側面からはコルテスとアステカ帝国の場合よりも遥かに少ない手勢でありながら、インカ帝国内の情勢などを利用しながら征服を成し遂げた点が異なると評される。ペルー国内では植民者や混血者の勢力においてはそのルーツとして讃えられる一方、先住民勢力などからは原住文化の破壊を齎したと批判されるなど評価は一定していない。1990年代には反ピサロの機運が高まり、故郷のエストラマドゥーラから贈られたピサロ像の撤去を求める動きが起きている。しかし2000年代に入って先進国であるヨーロッパやアメリカとの植民地時代を通じた繋がりを誇りとする風潮が生まれており、逆にピサロを再評価する流れも生じているという。

生涯

[編集]出自

[編集]フランシスコ・ピサロ・ゴンザレス(Francisco Pizarro González)はエストレマドゥーラ地方トルヒーリョで、カスティーリャ王冠領の小貴族ゴンサロ・ピサロ・ロドリゲス・デ・アギラール(Gonzalo Pizarro Rodríguez de Aguilar)の私生児として生まれた。生年については諸説あるが、1471年或いは1476年に生まれたと考えられている。父ピサロ・アギラールはカスティーリャ王軍の縦隊長を務め、イタリア戦争でゴンサロ・フェルナンデス・デ・コルドバ将軍の配下として戦っている。母フランシスカ・ゴンザレス・マテオス(Francisca González Mateos)は父の召使で、妾として父の子を儲けた。

ピサロは弟のゴンサロ・ピサロら兄弟と母方の一族で育てられ、生まれ故郷のトルヒーリョで貧しい少年期を過ごした。後に母が再婚すると異母弟フランシスコ・マルティン・デ・アルカンタラが兄弟に加わったが、彼も後に兄達とコンキスタドールの道を選んでいる[2]。また継父の血縁にはかのエルナン・コルテスが含まれている為、ピサロ兄弟とコルテスは親族の間柄となる[3]。ピサロは苦しい生活の中で貴族の子弟としての教育を受けられず、無骨な人物として育った[1]。Governor of Veragua

青年期のピサロについては少年期と同じく余り資料が残っておらず、航海士として歴史の表舞台に現れるまでの足取りは定かではない。現在でも諸説が存在する状態にあるが、特に歴史家アーサー・ヘルプスのイタリア戦争に参加していたという説が広く知られている。アーサーはピサロが武器の扱いや兵士の指揮などに手馴れていた点から航海以前に従軍経験を持っていたとするのが自然であるとし、その上で父の伝手からイタリア戦争に参加した可能性があると考えた。

中米での政争

[編集]ピサロが明確に歴史の表舞台に現れるのは1509年11月10日、カスティーリャ王国の騎士アロンソ・デ・オヘーダが新大陸航海を行った際、船団の航海者として記録された事による。航海の経験から冒険家に将来性を感じたピサロは航海士の道を選び、同郷出身で新大陸を南北に結ぶパナマ市などを支配下に治めていたベラグア属州領の総督バスコ・ヌーニェス・デ・バルボアの配下として新大陸での探検に参加した[1]。バルボアとピサロらは各地で先住民と接触しつつパナマ運河を越え、最終的に太平洋を発見するなど功績を残した。

1514年、パナマの支配に影響を及ぼすバルボアの存在はカスティーリャ王にとって疎ましい存在となっていた。国王の命令によってべラグア総督領はカスティーリャ・デ・オロ総督領に再編され、同時にバルボアは総督の地位を追われた。そして後任の総督としてペドロ・アリアス・デ・アビラが本国から派遣される事態になると、パナマ付近の有力者達はバルボア派とアビラ派に分かれて争いを始めた。当然ながらバルボア派に属していたピサロは密かに総督側と手を結び、エンコメンダール(殖民事業の許可)を得て独立したコンキスタドール(冒険家)としての一歩を踏み出した。

1519年、挽回を望むバルボアは大規模な征服事業に乗り出そうとしていたが、パナマ市に召還された際に総督側の騙し討ちにより捕らえられた。この時、バルボアを捕らえた総督側の軍勢を率いていたのは他でもないピサロであった。彼はかつての上司であり友人であるバルボアの首を刎ね、総督への反逆者として見せしめにした。一連の騒動で重要な役割を果たしたピサロは見返りとしてパナマ行政官の地位を与えられ、総督領の統治に関わる様になった。

対インカ戦争

[編集]南米征服への意欲

[編集]最初に南米西部に対する領土的野心を行動に移したのはバスク人の冒険家パスカル・デ・アンダゴヤによる1522年の遠征であると考えられている。パスカルは遠征の中で豊富な金山に恵まれた地域が南米にあり、その土地はヴィル(Viru)と呼ばれているとの噂を書き残した。パスカル自身は病に倒れて途中でパナマに引き返したが、南米の金山を巡る逸話はエル・ドラード(黄金郷)の伝説として取り分けコンキスタドール達の間で語り草になっていった。

自らの親族でもあるエルナン・コルテスが中米で先住民の大国アステカを滅ぼし、栄誉以上に莫大な金銀財宝を手にしたという話を聞いていたピサロにとっては特に興味深い話であった可能性はある。彼はコンキスタドール仲間でバルボアの配下時代からの友人であるディエゴ・デ・アルマグロ、総督領での改宗事業を行っていたヘルマンド・デ・ルクエ司教らと密議を交わし、具体的な遠征計画を立てた。三者は遠征での取り分を決め、争いを避ける為に遠征・殖民事業や利益分配についてはEmpresa del Levanteという会社組織を通じて行うものとする契約書も定められた。また遠征中の役割も話し合われ、指導者格のピサロが指揮官を務め、アルマグロが兵士や物資の調達を担当し、ルクエが財源管理を請負う事になった。

第一次遠征 (1524年)

[編集]On 13 September 1524, the first of three expeditions left from Panama for the conquest of Peru with about 80 men and 40 horses. Diego de Almagro was left behind because he was to recruit men, gather additional supplies, and join Pizarro later. The Governor of Panama, Pedro Arias Dávila, at first approved in principle of exploring South America. Pizarro's first expedition, however, turned out to be a failure as his conquistadors, sailing down the Pacific coast, reached no farther than Colombia before succumbing to such hardships as bad weather, lack of food, and skirmishes with hostile natives, one of which caused Almagro to lose an eye by arrow-shot. Moreover, the place names the Spanish bestowed along their route, including Puerto deseado (desired port), Puerto del hambre (port of hunger), and Puerto quemado (burned port), only confirm their straits. Fearing subsequent hostile encounters like the one the expedition endured at the Battle of Punta Quemada, Pizarro chose to end his tentative first expedition and return to Panama.

第二次遠征 (1526年)

[編集]Two years after the first very unsuccessful expedition, Pizarro, Almagro, and Luque started the arrangements for a second expedition with permission from Pedrarias Dávila. The Governor, who himself was preparing an expedition north to Nicaragua, was reluctant to permit another expedition, having lost confidence in the outcome of Pizarro's expeditions. The three associates, however, eventually won his trust and he acquiesced. Also by this time, a new governor was to arrive and succeed Pedrarias Dávila. This was Pedro de los Ríos, who took charge of the post in July 1526 and had manifested his initial approval of Pizarro's expeditions (he would later join him several years later in Peru).

In August 1526, after all preparations were ready, Pizarro left Panama with two ships with 160 men and several horses, reaching as far as the Colombian San Juan River. Soon after arriving the party separated, with Pizarro staying to explore the new and often perilous territory off the swampy Colombian coasts, while the expedition's second-in-command, Almagro, was sent back to Panama for reinforcements. Pizarro's Piloto Mayor (main pilot), Bartolomé Ruiz, continued sailing south and, after crossing the equator, found and captured a balsa (raft) of natives from Tumbes who were supervising the area. To everyone's surprise, these carried a load of textiles, ceramic objects, and some much-desired pieces of gold, silver, and emeralds, making Ruiz's findings the central focus of this second expedition which only served to pique the conquistadors' interests for more gold and land. Some of the natives were also taken aboard Ruiz's ship to serve later as interpreters.

He then set sail north for the San Juan river, arriving to find Pizarro and his men exhausted from the serious difficulties they had faced exploring the new territory. Soon Almagro also sailed into the port with his vessel laden with supplies, and a considerable reinforcement of at least eighty recruited men who had arrived at Panama from Spain with the same expeditionary spirit. The findings and excellent news from Ruiz along with Almagro's new reinforcements cheered Pizarro and his tired followers. They then decided to sail back to the territory already explored by Ruiz and, after a difficult voyage due to strong winds and currents, reached Atacames in the Ecuadorian coast. Here they found a very large native population recently brought under Inca rule. Unfortunately for the conquistadors, the warlike spirit of the people they had just encountered seemed so defiant and dangerous in numbers that the Spanish decided not to enter the land.

第三次遠征 (1526年)

[編集]After much wrangling between Pizarro and Almagro, it was decided that Pizarro would stay at a safer place, the Isla de Gallo, near the coast, while Almagro would return yet again to Panama with Luque for more reinforcements – this time with proof of the gold they had just found and the news of the discovery of an obvious wealthy land they had just explored. The new governor of Panama, Pedro de los Ríos, had learned of the mishaps of Pizarro's expeditions and the deaths of various settlers who had gone with him. Fearing an unsuccessful outcome, he outright rejected Almagro's application for a third expedition in 1527.

In addition, he ordered two ships commanded by Juan Tafur to be sent immediately with the intention of bringing Pizarro and everyone back to Panama. The leader of the expedition had no intention of returning, and when Tafur arrived at the now famous Isla de Gallo, Pizarro drew a line in the sand, saying: "There lies Peru with its riches; Here, Panama and its poverty. Choose, each man, what best becomes a brave Castilian."

Only thirteen men decided to stay with Pizarro and later became known as "The Famous Thirteen" (Los trece de la fama), while the rest of the expeditioners left back with Tafur aboard his ships. Ruiz also left in one of the ships with the intention of joining Almagro and Luque in their efforts to gather more reinforcements and eventually return to aid Pizarro. Soon after the ships left, the 13 men and Pizarro constructed a crude boat and left nine miles (14 km) north for La Isla Gorgona, where they would remain for seven months before the arrival of new provisions.

Back in Panama, Pedro de los Ríos (after much convincing by Luque) had finally acquiesced to the requests for another ship, but only to bring Pizarro back within six months and completely abandon the expedition. Both Almagro and Luque quickly grasped the opportunity and left Panama (this time without new recruits) for La Isla Gorgona to once again join Pizarro. On meeting with Pizarro, the associates decided to continue sailing south on the recommendations of Ruiz's Indian interpreters. By April 1528, they finally reached the northwestern Peruvian Tumbes Region. Tumbes became the territory of the first fruits of success the Spanish had so long desired, as they were received with a warm welcome of hospitality and provisions from the Tumpis, the local inhabitants. On subsequent days two of Pizarro's men reconnoitered the territory and both, on separate accounts, reported back the incredible riches of the land, including the decorations of silver and gold around the chief's residence and the hospitable attentions which they were received with by everyone. The Spanish also saw, for the first time, the Peruvian Llama which Pizarro called the "little camels". The natives also began calling the Spanish the "Children of the Sun" due to their fair complexion and brilliant armor. Pizarro, meanwhile, continued receiving the same accounts of a powerful monarch who ruled over the land they were exploring. These events only served as evidence to convince the expedition of the wealth and power displayed at Tumbes as an example of the riches the Peruvian territory had awaiting to conquer. The conquistadors decided to return to Panama to prepare the final expedition of conquest with more recruits and provisions. Before leaving, however, Pizarro and his followers sailed south not so far along the coast to see if anything of interest could be found. Historian William H. Prescott recounts that after passing through territories they named such as Cabo Blanco, port of Payta, Sechura, Punta de Aguja, Santa Cruz, and Trujillo (founded by Almagro years later), they finally reached for the first time the ninth degree of the southern latitude in South America. On their return towards Panama, Pizarro briefly stopped at Tumbes, where two of his men had decided to stay to learn the customs and language of the natives. Pizarro was also offered a native or two himself, one of which was later baptized as Felipillo and served as an important interpreter, the equivalent of Cortés' La Malinche of Mexico. Their final stop was at La Isla Gorgona, where two of his ill men (one had died) had stayed before. After at least eighteen months away, Pizarro and his followers anchored off the coasts of Panama to prepare for the final expedition.

トレド占領

[編集]When the new governor of Panama, Pedro de los Ríos, had refused to allow for a third expedition to the south, the associates resolved for Pizarro to leave for Spain and appeal to the sovereign in person. Pizarro sailed from Panama for Spain in the spring of 1528, reaching Seville in early summer. King Charles I, who was at Toledo, had an interview with Pizarro and heard of his expeditions in South America, a territory the conquistador described as very rich in gold and silver which he and his followers had bravely explored "to extend the empire of Castile." The King, who was soon to leave for Italy, was impressed at the accounts of Pizarro and promised to give his support for the conquest of Peru. It would be Queen Isabel, however, who, in the absence of the King, would sign the Capitulación de Toledo,[4] a license document which authorized Francisco Pizarro to proceed with the conquest of Peru. Pizarro was officially named the Governor, Captain General, and the "Adelantado" of the New Castile for the distance of 200 leagues along the newly discovered coast, and invested with all the authority and prerogatives, his associates being left in wholly secondary positions (a fact which later incensed Almagro and would lead to eventual discords with Pizarro). One of the conditions of the grant was that within six months Pizarro should raise a sufficiently equipped force of two hundred and fifty men, of whom one hundred might be drawn from the colonies.

This gave Pizarro time to leave for his native Trujillo and convince his brother Hernando Pizarro and other close friends to join him on his third expedition. Along with him also came Francisco de Orellana, who would later discover and explore the entire length of the Amazon River. Two more of his brothers, Juan Pizarro and Gonzalo Pizarro, would later decide to also join him as well as his cousin Pedro Pizarro who served as his page. When the expedition was ready and left the following year, it numbered three ships, one hundred and eighty men, and twenty-seven horses.

Since Pizarro could not meet the number of men the Capitulación had required, he sailed clandestinely from the port of Sanlúcar de Barrameda for the Canary Island of La Gomera in January 1530. He was there to be joined by his brother Hernando and the remaining men in two vessels that would sail back to Panama. Pizarro's third and final expedition left Panama for Peru on 27 December 1530.

インカ帝国滅亡

[編集]Template:Campaignbox Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire In 1532 Pizarro once again landed in the coasts near Ecuador, where some gold, silver, and emeralds were procured and then dispatched to Almagro, who had stayed in Panama to gather more recruits. Though Pizarro's main objective was then to set sail and dock at Tumbes like his previous expedition, he was forced to confront the Punian natives in the Battle of Puná, leaving three Spaniards dead and 400 dead or wounded Punians. Soon after, Hernando de Soto, another conquistador that had joined the expedition, arrived to aid Pizarro and with him sailed towards Tumbes, only to find the place deserted and destroyed. Their two fellow conquistadors expected they had disappeared or died under murky circumstances. The chiefs explained the fierce tribes of Punians had attacked them and ransacked the place.

As Tumbes no longer afforded the safe accommodations Pizarro sought, he decided to lead an excursion into the interior of the land and established the first Spanish settlement in Peru (third in South America after Santa Marta, Colombia in 1526), calling it San Miguel de Piura in July 1532. The first repartimiento in Peru was established here. After these events, Hernando de Soto was dispatched to explore the new lands and, after various days away, returned with an envoy from the Inca himself and a few presents with an invitation for a meeting with the Spaniards.

Following the defeat of his brother, Huáscar, Atahualpa had been resting in the Sierra of northern Peru, near Cajamarca, in the nearby thermal baths known today as the Baños del Inca (Incan Baths). After marching for almost two months towards Cajamarca, Pizarro and his force of just 106 foot-soldiers and 62 horsemen arrived and initiated proceedings for a meeting with Atahualpa. Pizarro sent Hernando de Soto, friar Vicente de Valverde and native interpreter Felipillo to approach Atahualpa at Cajamarca's central plaza. Atahualpa, however, refused the Spanish presence in his land by saying he would "be no man's tributary." His complacency, because there were fewer than 200 Spanish as opposed to his 80,000 soldiers sealed his fate and that of the Incan empire.

Atahualpa's refusal led Pizarro and his force to attack the Incan army in what became the Battle of Cajamarca on 16 November 1532. The Spanish were successful and Pizarro executed Atahualpa's 12-man honor guard and took the Inca captive at the so-called ransom room. Despite fulfilling his promise of filling one room (22フィート (7 m) by 17フィート (5 m))[5] with gold and two with silver, Atahualpa was convicted of killing his brother and plotting against Pizarro and his forces, and was executed by garrote on 26 July 1533. Pizarro wished to find a reason for executing Atahualpa without angering the people he was attempting to subdue. Pizarro's brother Hernando and de Soto opposed Atahualpa's execution, considering it an injustice. They objected to the evidence as wholly insufficient and were of the opinion that Pizzaro had no competence to sentence a sovereign prince in his own dominions.[6] King Charles wrote to Pizarro: "We have been displeased by the death of Atahualpa, since he was a monarch, and particularly as it was done in the name of justice."

A year later, Pizarro invaded Cuzco with indigenous troops and with it sealed the conquest of Peru. It is argued by some historians that the growing resistance from the new Inca, Manco Inca Yupanqui, prolonged the conquest. Manco Inca Yupanqui was the brother of the puppet ruler, Túpac Huallpa.

During the exploration of Cuzco, Pizarro was impressed and through his officers wrote back to King Charles I of Spain, saying:

"This city is the greatest and the finest ever seen in this country or anywhere in the Indies... We can assure your Majesty that it is so beautiful and has such fine buildings that it would be remarkable even in Spain."

After the Spanish had sealed the conquest of Peru by taking Cuzco in 1533, Jauja in the fertile Mantaro Valley was established as Peru's provisional capital in April 1534. But it was too far up in the mountains and far from the sea to serve as the Spanish capital of Peru. Pizarro thus founded the city of Lima in Peru's central coast on 18 January 1535, a foundation that he considered as one of the most important things he had created in life.

After the final effort of the Inca to recover Cuzco had been defeated by Almagro, a dispute occurred between him and Pizarro respecting the limits of their jurisdiction; both claimed the city of Cuzco. The king of Spain had awarded the Governorate of New Toledo to Almagro and the Governorate of New Castile to Pizarro. The dispute had originated from a disagreement on how to interpret the limit between both governorates. This led to confrontations between the Pizarro brothers and Almagro, who was eventually defeated during the Battle of Las Salinas (1538) and executed. Almagro's son, also named Diego and known as "El Mozo", was later stripped of his lands and left bankrupt by Pizarro.

Atahualpa's wife, ten year old Cuxirimay Ocllo Yupanqui, was with Atahualpa's army in Cajamarca and had stayed with him while he was imprisoned. Following his execution she was taken to Cuzco and given the name Dona Angelina. By 1538 it was known she was Pizarro's mistress, having borne him two sons, Juan and Francisco.[7]

Pizarro's death

[編集]

In Lima, Peru on 26 June 1541 "a group of twenty heavily armed supporters of Diego Almagro II stormed Pizarro's palace, assassinated him, and then forced the terrified city council to appoint young Almagro as the new governor of Peru", according to Burkholder and Johnson.[8] "Most of Pizarro's guests fled, but a few fought the intruders, numbered variously between seven and 25. While Pizarro struggled to buckle on his breastplate, his defenders, including his half-brother Alcántara, were killed. For his part Pizarro killed two attackers and ran through a third. While trying to pull out his sword, he was stabbed in the throat, then fell to the floor where he was stabbed many times."[9] Pizarro (who now was maybe as old as 70 years, and at least 62), collapsed on the floor, alone, painted a cross in his own blood and cried for Jesus Christ. He reportedly cried: Come my faithful sword, companion of all my deeds.[要出典] He died moments after. Diego de Almagro the younger was caught and executed the following year after losing the battle of Chupas.

Pizarro's remains were briefly interred in the cathedral courtyard; at some later time his head and body were separated and buried in separate boxes underneath the floor of the cathedral. In 1892, in preparation for the anniversary of Columbus' discovery of the Americas, a body believed to be that of Pizarro was exhumed and put on display in a glass coffin. However, in 1977 men working on the cathedral's foundation discovered a lead box in a sealed niche, which bore the inscription "Here is the head of Don Francisco Pizarro Demarkes, Don Francisco Pizarro who discovered Peru and presented it to the crown of Castile." A team of forensic scientists from the United States, led by Dr. William Maples, was invited to examine the two bodies, and they soon determined that the body which had been honored in the glass case for nearly a century had been incorrectly identified. The skull within the lead box not only bore the marks of multiple sword blows, but the features bore a remarkable resemblance to portraits made of the man in life.[10][11]

Personal

[編集]Pizarro had three sons and one daughter. A son whose name and mother are unknown died in 1544. He had two children by an Indian girl named Inés Huaillas Yupanqui: Gonzalo who was legitimized in 1537 and died when he was fourteen, and a daughter, Francisca, who was legitimized by imperial decree on 10 October 1537. Another son, Francisco, was sired upon a relative of Atahuallpa's but was never legitimized, and died shortly after his arrival in Spain.[1]

Legacy

[編集]

By his marriage to N de Trujillo, Pizarro had a son also named Francisco, who married his relative Inés Pizarro, without issue. After Pizarro's death, Inés Yupanqui, whom he took as a mistress, favourite sister of Atahualpa, who had been given to Francisco in marriage by her brother, married a Spanish cavalier named Ampuero and left for Spain, taking her daughter who would later be legitimized by imperial decree. Francisca Pizarro Yupanqui eventually married her uncle Hernando Pizarro in Spain, on 10 October 1537; a third son of Pizarro who was never legitimized, Francisco, by Dona Angelina, a wife of Atahualpa that he had taken as a mistress, died shortly after reaching Spain.[12]

Historians have often compared Pizarro and Cortés' conquests in North and South America as very similar in style and career. Pizarro, however, faced the Incas with a smaller army and fewer resources than Cortés at a much greater distance from the Spanish Caribbean outposts that could easily support him, which has led some to rank Pizarro slightly ahead of Cortés in their battles for conquest. Based on sheer numbers alone, Pizarro's military victory was one of the most improbable in recorded history. For example, Pizarro had fewer soldiers than George Armstrong Custer did at the Battle of the Little Big Horn, while the Incas commanded forty times as many soldiers as Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull did.

Though Pizarro is well known in Peru for being the leader behind the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire, a growing number of Peruvians regard him negatively. By taking advantage of the natives, Pizarro ruled Peru for almost a decade and initiated the decline of Inca culture. The Incas’ polytheistic religion was replaced by Christianity and both Quechua and Aymara — the main Inca languages — were reduced to a marginal role in society for centuries, while Spanish became the official language of Peru, Ecuador, Bolivia and Chile. The cities of the Inca Empire were transformed into Spanish, Catholic cities. Pizarro is also vilified for having ordered Atahualpa's death despite his paid ransom of filling a room with gold and two with silver which was later split among all his closest Spanish associates after a fifth share had been set aside for the king.

Sculptures

[編集]In the early 1930s, sculptor Ramsey MacDonald created three copies of an anonymous European foot soldier resembling a conquistador with a helmet, wielding a sword and riding a horse. The first copy was offered to Mexico to represent Hernán Cortés, though it was rejected. Since the Spanish conquerors had the same appearance with helmet and beard, the statue was taken to Lima in 1934. One other copy of the statue resides in Wisconsin. The mounted statue of Pizarro in the Plaza Major in Trujillo, Spain was created by Charles Rumsey, an American sculptor. It was presented to the city by his widow in 1926.

In 2003, after years of lobbying by indigenous and mixed-raced majority requesting for the equestrian statue of Pizarro to be removed, the mayor of Lima, Luis Castañeda Lossio, approved the transfer of the statue to another location: an adjacent square to the country's Government Palace. Since 2004, however, Pizarro's statue has been placed in a rehabilitated park surrounded by the recently restored 17th century pre-Hispanic murals in the Rímac District. The statue faces the Rímac River and the Government Palace.

The Palace of the conquest

[編集]

After their return from Peru and notoriously rich, the Pizarro family erected a plateresque-style palace on the corner of the Plaza Mayor in Trujillo, Spain. It was said to have been constructed on the orders of Pizarros daughter, Francisca Pizarro Yupanqui. It became an instant recognizable symbol of the plaza.

The opulent palace is structured in four stands, giving it the significance of the coat of arms of the Pizarro family, which is situated at one of its corner balconies displaying its iconographic content. At one of its sides it displays Francisco Pizarro and, at the other, his wife, the Inca princess Inés Huaylas, along with their daughter Francisca Pizarro Yupanqui and her husband Hernando Pizarro. The building's decor includes plateresque ornaments and balustrades.

In popular culture

[編集]

- Pizarro is the title and subject of a dramatic tragedy by Richard Brinsley Sheridan, presented in 1799.[13] Sheridan based his work on the German tragedy by August von Kotzebue, Die Spanier in Peru.

- Francisco Pizarro is depicted as a villain in the 1980s animated series The Mysterious Cities of Gold. In it, Pizarro is a ruthless conqueror of the Incas who values gold above all else.

- Ron Pardo portrays Francisco Pizarro in an episode of History Bites as a parody of actor William Shatner's portrayal of James T. Kirk, captain of the starship Enterprise in the 1960s television series Star Trek.

- Francisco Pizarro is the main character in Peter Schaffer's play The Royal Hunt of the Sun.

- Pizarro is a character in the novel Inés of My Soul (Inés del alma mía) by Isabel Allende (HarperCollins, 2006).

- In Jared Diamond's Pulitzer Prize winning book, Guns, Germs, and Steel, the Battle of Cajamarca is used to introduce Diamond's theory: Eurasian hegemony stems from environmental factors alone.

- In the book Evil Star from the Power of Five series by Anthony Horowitz, a historian claims a monk travelled with Pizarro to Peru and discovered an alternate creation story recorded by the Incas.

- Analog Science Fiction and Fact, in Anthology 4, "Analog's Lighter Side", featured a story, "Despoilers of the Golden Empire", which recast the conquest of Peru as a sci-fi story.

| 官職 | ||

|---|---|---|

| 先代 Position founded |

Governor of New Castile 1528–1541 |

次代 Cristóbal Vaca de Castro |

Ancestry

[編集]| Sarandora/試訳中記事1の系譜 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Works of Pizarro

[編集]- Francisco Pizarro. “Cartas del Marqués Don Francisco Pizarro (1533-1541)”. www.bloknot.info (A.Skromnitsky). 2009年10月10日閲覧。

- Francisco Pizarro. “Cédula de encomienda de Francisco Pizarro a Diego Maldonado, Cuzco, 15 de abril de 1539”. www.bloknot.info (A.Skromnitsky). 2009年10月10日閲覧。

Footnotes

[編集]- ^ a b c d e “Francisco Pizarro”. The Catholic Encyclopedia. 11 January 2012閲覧。

- ^ “Pizarro”. Euskalnet.net. 2011年4月20日閲覧。

- ^ Machado, J. T. Montalvão, Dos Pizarros de Espanha aos de Portugal e Brasil, Author's Edition, 1st Edition, Lisbon, 1970.

- ^ college.hmco.com

- ^ Francisco Pizarro, Catholic Encyclopedia.

- ^ fullbooks.com

- ^ Juan de Betanzos Narratives of the Incas ed. Dana Buchanan, tr. Roland Hamilton University of Texas Press, 1996 Pg 265 ISBN 0-292-75559-7 Following Pizarro's assassination Dona Angelina married the interpreter Juan de Betanzos.

- ^ Burkholder, Mark A., Johnson, Lyman L. Colonial Latin America. Oxford University Press, USA, 5th edition (23 October 2003). p59 (ISBN 0-19-515685-4)

- ^ "Exploring the Inca Heartland: Pizarro's Family and His Head", Archaeology, Archaeological Institute of America. 1 September 1999.

- ^ Maples, WR; Gatliff, BP; Ludeña, H; Benfer, R; Goza, W (1989). “The death and mortal remains of Francisco Pizarro”. Journal of forensic sciences 34 (4): 1021–36. PMID 2668443.

- ^ Maxey, R. "The Misplaced Conquistador-Francisco Pizarro."

- ^ Prescott, William. History of the Conquest of Peru, chapter 28.

- ^ The New Cambridge Bibliography of English Literature: Volume 2; Volumes 1660-1800. Books.google.co.uk. (1971-07-30). ISBN 978-0-521-07934-1 2011年4月20日閲覧。

References

[編集]- ""Cajamarca o la Leyenda Negra, a Tragedy for the Theater in Spanish by Santiago Sevilla in Liceus El Portal de las Humanidades, Liceus.com

- Pizarro, a tragedy, by Richard Brinsley Sheridan, in Google books

- Conquest of the Incas, John Hemming, 1973. ISBN 0-15-602826-3

- Francisco Pizarro and the Conquést of the Inca by Gina DeAngelis, 2000. ISBN 0-613-32584-2

- The Discovery and Conquest of Peru by William H. Prescott ISBN 0-7607-6137-X

External links

[編集]- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1900). Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography (英語). New York: D. Appleton.

Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1900). Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography (英語). New York: D. Appleton. {{cite encyclopedia}}:|title=は必須です。 (説明)- PBS Special: Conquistadors — Pizarro and the conquest of the Incas

- Francisco Pizarro, a Head of His Time

- The Conquest of the Incas by Pizarro - UC Press

- The European Voyages of Exploration

- 図書館にあるSarandora/試訳中記事1に関係する蔵書一覧 - WorldCatカタログ

- "Francisco Pizarro", February 1992, National Geographic

- Relacion de los primeros descubrimientos de Francisco Pizarro y Diego de Almagro, 1526 In Spanish. BlokNOT (A. Skromnitsky). 2009-10-09. Colleccion de documentos ineditos para la historia de Espana. Tomo V. — Madrid, 1844

- 1470s births

- 1541 deaths

- 16th-century Spanish people

- Assassinated Spanish people

- Burials at the Cathedral of Lima

- City founders

- Explorers of North America

- Explorers of South America

- Extremaduran conquistadors

- History of Peru

- People from the Province of Cáceres

- People murdered in Peru

- Spanish conquistadors

- Spanish nobility

- Spanish people murdered abroad

- Spanish explorers