利用者:Bluesnow/サブページ

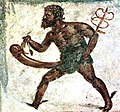

ポンペイとヘルクラネウムのエロチック・アート(Erotic art in Pompeii and Herculaneum)とは、18世紀に始まった広範囲にわたる発掘調査の結果、ナポリ湾周辺の古代遺跡(特にポンペイとヘルクラネウム(en))で発見された壁画群をいう。

The city was found to be full of erotic artとフレスコ, symbols, and inscriptions regarded by its excavators as ポルノグラフィ. Even many recovered household items had a sexual theme. The ubiquity of such imagery and items indicates that the sexual 慣習(en) of 古代ローマ文化(en) of the time were much more liberal than most present-day cultures, although much of what might seem to us to be erotic imagery (eg oversized phalluses) was in fact fertility-imagery. This カルチャーショック led to an unknown number of discoveries being hidden away again. For example, a フレスコ壁画 which depicted プリアポス(en), the ancient god of sex and fertility, with his extremely enlarged ペニス, was covered with plaster (and, as カール・シェフォールト(en explains (p. 134), even the older reproduction below was locked away "out of prudishness" and only opened on request) and only rediscovered in 1998年 due to rainfall [1].

In 1819年, when 両シチリア王フランチェスコ1世 visited the Pompeii exhibition at ナポリ国立考古学博物館(en) with his wife and daughter, he was so embarrassed by the erotic artwork that he decided to have it locked away in a secret cabinet, accessible only to "people of mature age and respected morals". Re-opened, closed, re-opened again and then closed again for nearly 100 years, it was briefly made accessible again at the end of the 1960年代 (the time of the 性の革命) and was finally re-opened for viewing in 2000年. Minors are still only allowed entry to the once secret cabinet in the presence of a guardian or with written permission.

有名な例

[編集]ファロス

[編集]-

壁に描かれたメルクリウスもしくはプリアポス

銅像 wind chimes of "ファロス(en)-animals" were common household items. Note the child on one of the wind chimes -- the large phallus (whether on Pan, Priapus or a similar deity, or on its own) was not seen as threatening or erotic, but as a fertility symbol.

売春宿

[編集]-

ポンペイのエロチックな壁画

It is unclear whether the images on the walls were advertisements for the services offered or merely intended to heighten the pleasure of the visitors. As previously mentioned, some of the paintings and frescoes became immediately famous because they represented erotic, sometimes explicit, sexual scenes. One of the most curious buildings recovered was in fact a Lupanare (売春), which had many erotic paintings and graffiti inside. The erotic paintings seem to present an idealised vision of sex at odds with the reality of the function of the lupanare. 売春宿(Lupanar (Pompeii)) had 10 rooms (cubicula, 5 per floor), a balcony, and a latrina. It was one of the larger houses, perhaps the largest, but not the only brothel. The town seems to have been oriented to a warm consideration of sensual matters: on a wall of the バシリカ (sort of a civil tribunal, thus frequented by many Roman tourists and travelers), an immortal inscription tells the foreigner, If anyone is looking for some tender love in this town, keep in mind that here all the girls are very friendly (loose translation). Other inscriptions reveal some pricing information for various services: Athenais 2 アス(en), Sabina 2 As (CIL IV, 4150), The house slave Logas, 8 As (CIL IV, 5203) or Maritimus licks your 女性器 for 4 As. He is ready to serve virgins as well. (CIL IV, 8940). The amounts vary from one to two As up to several Sesterces. In the lower price range the service was not more expensive than a loaf of bread. Prostitution was relatively inexpensive for the Roman male but it is important to note that even a low priced prostitute earned more than three times the wages of an unskilled urban laborer. However, it was unlikely a freed woman would enter the profession in hopes for wealth because most women declined in their economic status and standard of living due to demands on their appearance as well as their health. Prostitution was overwhelmingly an urban creation. Within the brothel it is said prostitutes worked in a small room usually with an entrance marked by a patchwork curtain. Sometimes the woman's name and price would be placed above her door. Sex was generally the cheapest in Pompeii, compared to other parts of the Empire. Although an estimation of price is difficult to guess, one should suspect the prostitute's age, appearance, and skill level would play a part in the price. All services were paid for with cash.

郊外の浴場

[編集]Also, in the Thermae suburbanae (near Porta Marina - [1]), the only known Roman artwork describing a サッポー風 (レズビアン) scene was recently discovered.

These pictures were found in a changing room at one side of the newly excavated Suburban Baths in the early 1990s. The function of these pictures is not yet clear: some authors say that they indicate that the services of prostitutes were available on the upper floor of the bathhouse and could perhaps be a sort of advertising, while others prefer the hypothesis that their only purpose was to decorate the walls with joyful scenes (as these were in Roman culture). The most widely accepted theory, that of the original archaeologist, Luciana Jacobelli, is that they served as reminders of where one had left one's clothes. The Thermae were, however, used in common by males and females, although baths in other areas (even within Pompeii) were often segregated by sex.

Collected below are high quality images of erotic frescoes, mosaics, statues and other objects from Pompeii and Herculaneum.

片方の貝殻の中のウェヌス

[編集]

The mural of ウェヌス from Pompeii was never seen by ボッティチェッリ, the painter of ヴィーナスの誕生, but may have been a Roman copy of the then famous painting by アペレス(en) which Lucian mentioned. In classical antiquity, the 貝殻 was a メタファー for a 女性の性器.

発見された作品

[編集]画像

[編集]-

From Casa del Centenario. Note that the woman is wearing a primitive ブラジャー.

-

Marble sculpture, Pan & goat, Herculaneum

関連項目

[編集]脚註

[編集]外部リンク

[編集]参考文献とさらに知りたい人のために

[編集]- Michael Grant and Antonia Mulas, Eros in Pompeii: The Erotic Art Collection of the Museum of Naples. New York: Stewart, Tabori and Chang, 1997.

- Thomas A.J. McGinn, The Economy of Prostitution in the Roman World. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2004.

- Antonio Varone, Eroticism in Pompeii. Getty Trust Publications: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2001.

![郊外の浴場のフレスコ壁画より[2]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e1/Sexual_scene_on_pompeian_mural.jpg/120px-Sexual_scene_on_pompeian_mural.jpg)