利用者:紅い目の女の子/下書き3

応用

[編集]

対数の概念は、数学の内外で広く応用される。これらの中には、スケール不変性に関連するものもある。例えば、オウムガイの貝の各区画は隣接する区画とほぼ相似で、一定の割合で拡縮されている。これによって対数らせんが生じる[1]。 ベンフォードの法則として知られる数値の最初の桁に現れる数の分布に関する規則性も、スケール不変性で説明できる[2]。 対数は、自己相似性の概念とも関連がある。例えば、分割統治法と呼ばれる、ある問題をより小さな2つの問題に分割して解き、その結果を併せることで元の問題を解くアルゴリズムについて解析すると、対数が現れる[3]。自己相似な幾何図形、すなわち一部分の構造が全体と相似であるようなものの次元は、対数を用いて定義される。

対数スケールは、絶対的な値の差よりも相対的な変化を定量的に測るのに有益である。また、対数函数log(x)はxが十分大きい時に緩やかにしか増加しないので、分布する値の幅が広いデータを圧縮して表すのにも用いられる。他にもツィオルコフスキーの公式やFenske方程式、ネルンストの式など、様々な科学の法則に認められる。

対数スケール

[編集]

科学的な数量は、しばしば対数スケールを用いて他の数量の対数で表されることがある。例えば、デシベルという単位は、レベル表現、すなわち対数スケールが用いられている。この単位は、基準値に対する比の常用対数によって定義される。電力であれば、電力の値の比の常用対数の10倍、電圧であれば電圧比の常用対数の20倍というようになる。 It is used to quantify the loss of voltage levels in transmitting electrical signals,[4] to describe power levels of sounds in acoustics,[5] and the absorbance of light in the fields of spectrometry and optics. The signal-to-noise ratio describing the amount of unwanted noise in relation to a (meaningful) signal is also measured in decibels.[6] In a similar vein, the peak signal-to-noise ratio is commonly used to assess the quality of sound and image compression methods using the logarithm.[7]

The strength of an earthquake is measured by taking the common logarithm of the energy emitted at the quake. This is used in the moment magnitude scale or the Richter magnitude scale. For example, a 5.0 earthquake releases 32 times (101.5) and a 6.0 releases 1000 times (103) the energy of a 4.0.[8] Apparent magnitude measures the brightness of stars logarithmically.[9] In chemistry the negative of the decimal logarithm, the decimal cologarithm, is indicated by the letter p.[10] For instance, pH is the decimal cologarithm of the activity of hydronium ions (the form hydrogen ions H+ take in water).[11] The activity of hydronium ions in neutral water is 10−7 mol·L−1, hence a pH of 7. Vinegar typically has a pH of about 3. The difference of 4 corresponds to a ratio of 104 of the activity, that is, vinegar's hydronium ion activity is about 10−3 mol·L−1.

Semilog (log–linear) graphs use the logarithmic scale concept for visualization: one axis, typically the vertical one, is scaled logarithmically. For example, the chart at the right compresses the steep increase from 1 million to 1 trillion to the same space (on the vertical axis) as the increase from 1 to 1 million. In such graphs, exponential functions of the form f(x) = a · bx appear as straight lines with slope equal to the logarithm of b. Log-log graphs scale both axes logarithmically, which causes functions of the form f(x) = a · xk to be depicted as straight lines with slope equal to the exponent k. This is applied in visualizing and analyzing power laws.[12]

Psychology

[編集]Logarithms occur in several laws describing human perception:[13][14] Hick's law proposes a logarithmic relation between the time individuals take to choose an alternative and the number of choices they have.[15] Fitts's law predicts that the time required to rapidly move to a target area is a logarithmic function of the distance to and the size of the target.[16] In psychophysics, the Weber–Fechner law proposes a logarithmic relationship between stimulus and sensation such as the actual vs. the perceived weight of an item a person is carrying.[17] (This "law", however, is less realistic than more recent models, such as Stevens's power law.[18])

Psychological studies found that individuals with little mathematics education tend to estimate quantities logarithmically, that is, they position a number on an unmarked line according to its logarithm, so that 10 is positioned as close to 100 as 100 is to 1000. Increasing education shifts this to a linear estimate (positioning 1000 10 times as far away) in some circumstances, while logarithms are used when the numbers to be plotted are difficult to plot linearly.[19][20]

Probability theory and statistics

[編集]

Logarithms arise in probability theory: the law of large numbers dictates that, for a fair coin, as the number of coin-tosses increases to infinity, the observed proportion of heads approaches one-half. The fluctuations of this proportion about one-half are described by the law of the iterated logarithm.[21]

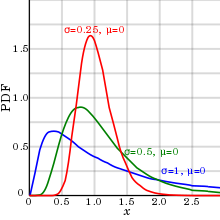

Logarithms also occur in log-normal distributions. When the logarithm of a random variable has a normal distribution, the variable is said to have a log-normal distribution.[22] Log-normal distributions are encountered in many fields, wherever a variable is formed as the product of many independent positive random variables, for example in the study of turbulence.[23]

Logarithms are used for maximum-likelihood estimation of parametric statistical models. For such a model, the likelihood function depends on at least one parameter that must be estimated. A maximum of the likelihood function occurs at the same parameter-value as a maximum of the logarithm of the likelihood (the "log likelihood"), because the logarithm is an increasing function. The log-likelihood is easier to maximize, especially for the multiplied likelihoods for independent random variables.[24]

Benford's law describes the occurrence of digits in many data sets, such as heights of buildings. According to Benford's law, the probability that the first decimal-digit of an item in the data sample is d (from 1 to 9) equals log10 (d + 1) − log10 (d), regardless of the unit of measurement.[25] Thus, about 30% of the data can be expected to have 1 as first digit, 18% start with 2, etc. Auditors examine deviations from Benford's law to detect fraudulent accounting.[26]

計算量

[編集]計算機科学の一分野であるアルゴリズム解析は、アルゴリズムの計算量を研究するものである[27]。対数は、分割統治法のような大きな問題を小さな問題に分割し、小さな問題の解を結合することで元の問題を解くようなアルゴリズムを評価するのに有用である[28]。

例えば、予め並び替えられている数列から、特定の数を探すことを考える。二分探索法は所望の数が見つかるまで、数列のちょうど中央の数と探している対象の数を比較し、数列の前半と後半のどちらに探している数が含まれるかを判定することを繰り返す方法である。このアルゴリズムは、数列の長さをNとすると、平均でlog2 (N)回の比較が必要になる[29]。 似たような例として、マージソートというソートアルゴリズムを考える。マージソートは、未ソートの数列を二分割し、それぞれをソートした上で最終的に分割した数列を結合するソートアルゴリズムである。マージソートの時間計算量はおおよそN · log(N)に比例する [30]。ここで対数の底を指定していないのは、底を取り換えても定数倍の差しか生じないからである。標準的な時間計算量の見積もりでは、通常定数係数は無視される[31]。

関数f(x)がxの対数に比例しているとき、f(x)は対数的に増加しているという。例えば、任意の自然数Nは、2進表現に変換するとlog2 N + 1ビットで表せる。言い換えると、自然数Nを保持するのに必要なメモリ量は、Nについて対数的に増加する。

Entropy and chaos

[編集]

エントロピーは、広義には系の乱雑さの度合いを測る尺度のことである。統計熱力学では、ある系のエントロピー S は次のように定義される。

ここで i はとりうる状態それぞれを表す添え字で、piはその系においてiが表す状態をとる確率、k はボルツマン定数を表す。エントロピーの定義で i について総和をとるのは、考えている系において取りうる全ての状態に対する和をとることに相当し、例えばある容器に入っている気体の気体分子の位置全てのパターンに対して総和をとることが挙げられる。 Entropy is broadly a measure of the disorder of some system. In statistical thermodynamics, the entropy S of some physical system is defined as

The sum is over all possible states i of the system in question, such as the positions of gas particles in a container. Moreover, pi is the probability that the state i is attained and k is the Boltzmann constant. Similarly, entropy in information theory measures the quantity of information. If a message recipient may expect any one of N possible messages with equal likelihood, then the amount of information conveyed by any one such message is quantified as log2 N bits.[32]

Lyapunov exponents use logarithms to gauge the degree of chaoticity of a dynamical system. For example, for a particle moving on an oval billiard table, even small changes of the initial conditions result in very different paths of the particle. Such systems are chaotic in a deterministic way, because small measurement errors of the initial state predictably lead to largely different final states.[33] At least one Lyapunov exponent of a deterministically chaotic system is positive.

Fractals

[編集]

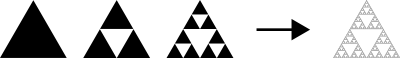

Logarithms occur in definitions of the dimension of fractals.[34] Fractals are geometric objects that are self-similar: small parts reproduce, at least roughly, the entire global structure. The Sierpinski triangle (pictured) can be covered by three copies of itself, each having sides half the original length. This makes the Hausdorff dimension of this structure ln(3)/ln(2) ≈ 1.58. Another logarithm-based notion of dimension is obtained by counting the number of boxes needed to cover the fractal in question.

Music

[編集]Logarithms are related to musical tones and intervals. In equal temperament, the frequency ratio depends only on the interval between two tones, not on the specific frequency, or pitch, of the individual tones. For example, the note A has a frequency of 440 Hz and B-flat has a frequency of 466 Hz. The interval between A and B-flat is a semitone, as is the one between B-flat and B (frequency 493 Hz). Accordingly, the frequency ratios agree:

Therefore, logarithms can be used to describe the intervals: an interval is measured in semitones by taking the base-21/12 logarithm of the frequency ratio, while the base-21/1200 logarithm of the frequency ratio expresses the interval in cents, hundredths of a semitone. The latter is used for finer encoding, as it is needed for non-equal temperaments.[35]

| Interval (the two tones are played at the same time) |

1/12 tone |

Semitone |

Just major third |

Major third |

Tritone |

Octave |

| Frequency ratio r | ||||||

| Corresponding number of semitones |

||||||

| Corresponding number of cents |

Number theory

[編集]Natural logarithms are closely linked to counting prime numbers (2, 3, 5, 7, 11, ...), an important topic in number theory. For any integer x, the quantity of prime numbers less than or equal to x is denoted π(x). The prime number theorem asserts that π(x) is approximately given by

in the sense that the ratio of π(x) and that fraction approaches 1 when x tends to infinity.[36] As a consequence, the probability that a randomly chosen number between 1 and x is prime is inversely proportional to the number of decimal digits of x. A far better estimate of π(x) is given by the offset logarithmic integral function Li(x), defined by

The Riemann hypothesis, one of the oldest open mathematical conjectures, can be stated in terms of comparing π(x) and Li(x).[37] The Erdős–Kac theorem describing the number of distinct prime factors also involves the natural logarithm.

The logarithm of n factorial, n! = 1 · 2 · ... · n, is given by

This can be used to obtain Stirling's formula, an approximation of n! for large n.[38]

脚注

[編集]注釈

[編集]出典

[編集]- ^ Maor 2009, p. 135

- ^ Frey, Bruce (2006), Statistics hacks, Hacks Series, Sebastopol, CA: O'Reilly, ISBN 978-0-596-10164-0, chapter 6, section 64

- ^ Ricciardi, Luigi M. (1990), Lectures in applied mathematics and informatics, Manchester: Manchester University Press, ISBN 978-0-7190-2671-3, p. 21, section 1.3.2

- ^ Bakshi, U.A. (2009), Telecommunication Engineering, Pune: Technical Publications, ISBN 978-81-8431-725-1, section 5.2

- ^ Maling, George C. (2007), “Noise”, in Rossing, Thomas D., Springer handbook of acoustics, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-30446-5, section 23.0.2

- ^ Tashev, Ivan Jelev (2009), Sound Capture and Processing: Practical Approaches, New York: John Wiley & Sons, p. 98, ISBN 978-0-470-31983-3

- ^ Chui, C.K. (1997), Wavelets: a mathematical tool for signal processing, SIAM monographs on mathematical modeling and computation, Philadelphia: Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, ISBN 978-0-89871-384-8

- ^ Crauder, Bruce; Evans, Benny; Noell, Alan (2008), Functions and Change: A Modeling Approach to College Algebra (4th ed.), Boston: Cengage Learning, ISBN 978-0-547-15669-9, section 4.4.

- ^ Bradt, Hale (2004), Astronomy methods: a physical approach to astronomical observations, Cambridge Planetary Science, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-53551-9, section 8.3, p. 231

- ^ Nørby, Jens (2000). “The origin and the meaning of the little p in pH”. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 25 (1): 36–37. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(99)01517-0. PMID 10637613.

- ^ IUPAC (1997), A. D. McNaught, A. Wilkinson, ed., Compendium of Chemical Terminology ("Gold Book") (2nd ed.), Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications, doi:10.1351/goldbook, ISBN 978-0-9678550-9-7

- ^ Bird, J.O. (2001), Newnes engineering mathematics pocket book (3rd ed.), Oxford: Newnes, ISBN 978-0-7506-4992-6, section 34

- ^ Goldstein, E. Bruce (2009), Encyclopedia of Perception, Encyclopedia of Perception, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, ISBN 978-1-4129-4081-8, pp. 355–56

- ^ Matthews, Gerald (2000), Human Performance: Cognition, Stress, and Individual Differences, Hove: Psychology Press, ISBN 978-0-415-04406-6, p. 48

- ^ Welford, A.T. (1968), Fundamentals of skill, London: Methuen, ISBN 978-0-416-03000-6, OCLC 219156, p. 61

- ^ Paul M. Fitts (June 1954), “The information capacity of the human motor system in controlling the amplitude of movement”, Journal of Experimental Psychology 47 (6): 381–91, doi:10.1037/h0055392, PMID 13174710, reprinted in Paul M. Fitts (1992), “The information capacity of the human motor system in controlling the amplitude of movement”, Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 121 (3): 262–69, doi:10.1037/0096-3445.121.3.262, PMID 1402698 30 March 2011閲覧。

- ^ Banerjee, J.C. (1994), Encyclopaedic dictionary of psychological terms, New Delhi: M.D. Publications, p. 304, ISBN 978-81-85880-28-0, OCLC 33860167

- ^ Nadel, Lynn (2005), Encyclopedia of cognitive science, New York: John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-470-01619-0, lemmas Psychophysics and Perception: Overview

- ^ Siegler, Robert S.; Opfer, John E. (2003), “The Development of Numerical Estimation. Evidence for Multiple Representations of Numerical Quantity”, Psychological Science 14 (3): 237–43, doi:10.1111/1467-9280.02438, PMID 12741747, オリジナルの17 May 2011時点におけるアーカイブ。 7 January 2011閲覧。

- ^ Dehaene, Stanislas; Izard, Véronique; Spelke, Elizabeth; Pica, Pierre (2008), “Log or Linear? Distinct Intuitions of the Number Scale in Western and Amazonian Indigene Cultures”, Science 320 (5880): 1217–20, Bibcode: 2008Sci...320.1217D, doi:10.1126/science.1156540, PMC 2610411, PMID 18511690

- ^ Breiman, Leo (1992), Probability, Classics in applied mathematics, Philadelphia: Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, ISBN 978-0-89871-296-4, section 12.9

- ^ Aitchison, J.; Brown, J.A.C. (1969), The lognormal distribution, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-04011-2, OCLC 301100935

- ^ Jean Mathieu and Julian Scott (2000), An introduction to turbulent flow, Cambridge University Press, p. 50, ISBN 978-0-521-77538-0

- ^ Rose, Colin; Smith, Murray D. (2002), Mathematical statistics with Mathematica, Springer texts in statistics, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-95234-5, section 11.3

- ^ Tabachnikov, Serge (2005), Geometry and Billiards, Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society, pp. 36–40, ISBN 978-0-8218-3919-5, section 2.1

- ^ Durtschi, Cindy; Hillison, William; Pacini, Carl (2004), “The Effective Use of Benford's Law in Detecting Fraud in Accounting Data”, Journal of Forensic Accounting V: 17–34, オリジナルの29 August 2017時点におけるアーカイブ。 28 May 2018閲覧。

- ^ Wegener, Ingo (2005), Complexity theory: exploring the limits of efficient algorithms, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-540-21045-0, pp. 1–2

- ^ Harel, David; Feldman, Yishai A. (2004), Algorithmics: the spirit of computing, New York: Addison-Wesley, ISBN 978-0-321-11784-7, p. 143

- ^ Knuth, Donald (1998), The Art of Computer Programming, Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, ISBN 978-0-201-89685-5, section 6.2.1, pp. 409–26

- ^ Donald Knuth 1998, section 5.2.4, pp. 158–68

- ^ Wegener, Ingo (2005), Complexity theory: exploring the limits of efficient algorithms, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, p. 20, ISBN 978-3-540-21045-0

- ^ Eco, Umberto (1989), The open work, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-63976-8, section III.I

- ^ Sprott, Julien Clinton (2010), “Elegant Chaos: Algebraically Simple Chaotic Flows”, Elegant Chaos: Algebraically Simple Chaotic Flows. Edited by Sprott Julien Clinton. Published by World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd (New Jersey: World Scientific), Bibcode: 2010ecas.book.....S, doi:10.1142/7183, ISBN 978-981-283-881-0, section 1.9

- ^ Helmberg, Gilbert (2007), Getting acquainted with fractals, De Gruyter Textbook, Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-019092-2

- ^ Wright, David (2009), Mathematics and music, Providence, RI: AMS Bookstore, ISBN 978-0-8218-4873-9, chapter 5

- ^ Bateman, P.T.; Diamond, Harold G. (2004), Analytic number theory: an introductory course, New Jersey: World Scientific, ISBN 978-981-256-080-3, OCLC 492669517, theorem 4.1

- ^ P. T. Bateman & Diamond 2004, Theorem 8.15

- ^ Slomson, Alan B. (1991), An introduction to combinatorics, London: CRC Press, ISBN 978-0-412-35370-3, chapter 4

![{\displaystyle {\frac {466}{440}}\approx {\frac {493}{466}}\approx 1.059\approx {\sqrt[{12}]{2}}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/55acf246da64ba711e1717eb43ad81792220ab32)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}2^{\frac {4}{12}}&={\sqrt[{3}]{2}}\\&\approx 1.2599\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/76610ca7878ea438fa73bd50ac4df1fecce09b9f)

![{\displaystyle \log _{\sqrt[{12}]{2}}(r)=12\log _{2}(r)}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/173477b6bc89e2396abacc83ca5015ac01b0747b)

![{\displaystyle \log _{\sqrt[{1200}]{2}}(r)=1200\log _{2}(r)}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a1ccc3b05bf5ae0d41f85c50ab1a7ceec4e95713)