利用者:河内蜻蛉/sandbox

|

ここは河内蜻蛉さんの利用者サンドボックスです。編集を試したり下書きを置いておいたりするための場所であり、百科事典の記事ではありません。ただし、公開の場ですので、許諾されていない文章の転載はご遠慮ください。

登録利用者は自分用の利用者サンドボックスを作成できます(サンドボックスを作成する、解説)。 その他のサンドボックス: 共用サンドボックス | モジュールサンドボックス 記事がある程度できあがったら、編集方針を確認して、新規ページを作成しましょう。 |

太字 スイス

- 番号なし箇条書き

十裁判区同盟

-

xxxx年 - xxxx年 -

首都 不明 - 元首等

-

xxxx年 - xxxx年 不明 - 変遷

-

不明 xxxx年xx月xx日

{{Quote|あ|言った人|引用文の出所}}

{{Quote|あ|言った人|引用文の出所}}

#REDIRECT [[三同盟]]

kiosukuは駅の中—ドミトリ、ココナッツ

| 「 | ああああああああああああああああああああああああああああああああああああああああああああああああああああ | 」 |

| {{{州名}}}州 {{{英語州名}}} | |

|---|---|

| 州旗・州章 | |

|

[[File:{{{州章}}}|200px]] | |

|

[[File:{{{州旗}}}|200px]] | |

| 位置 | |

|

[[File:{{{位置地図}}}|200px]] | |

|

[[File:{{{位置地図2}}}|200px]] | |

| 行政 | |

| 国: |

|

| 地方行政区画 | |

| 行政区 | {{{行政区のドイツ語名}}} |

| 基礎自治体 | {{{ドイツ語名}}}({{{カタカナ}}}) |

| 統計 | |

| 州都 | {{{州都}}} |

| 言語 | [[{{{使用言語}}}]] |

| 面積 | {{{面積}}} km² |

| 人口({{{人口統計年}}}年) • 人口密度: |

{{{人口}}}人 • {{{人口密度}}}人/km² |

| ISO 3166: | {{{ISO 3166コード}}} |

| マック | マク | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 行為 | レーキング | マックレーキング

113件 |

マクレーキング

不明 |

| レイキング | マックレイキング

147件 |

マクレイキング

3件 | |

| 人 | レーカー | マックレーカー

942件 |

マクレーカー

70件 |

| レイカー | マックレイカー

1380件 |

マクレイカー

139件 |

muckraking

→muck: 泥、堆肥なので「マック」*「マク」は明らかに原音に対して誤り

→raking: 掻き入れること、熊手は日本語で「レーキ」(「レイキ」とは言わない)

デジタル大辞泉

- 「マックレーカー【muckraker】《肥やしをかき集める熊手の意》政治家や公務員などの不正や醜聞をあさり、暴露して書きたてる記者。」

情報・知識 imidas 2018

- 「[muckraker]醜聞を暴く人.腐敗暴露記者.20世紀初めにニューヨーク市当局の腐敗を糾弾した記者を,ルーズベルト大統領がこのように呼んだ。」

小学館 ランダムハウス英和大辞典

- 「múck・ràke v.i. (特に政界の)醜聞[汚職など]を暴露する.」

岩波 世界人名大辞典

- 「ロイド Lloyd, Henry Demarest 1847.5.1~1903.9.28

アメリカの法律家,ジャーナリスト.

弁護士 [1869] .《シカゴ・トリビューン》紙記者 [72-85] .ロックフェラー財閥の内幕を暴露し,またスプリング・ヴァレー炭鉱のストライキに際しては,組合に加えられたテロ行為を指摘し,いわゆるマックレーカー(不正・醜聞を暴くジャーナリストや作家)として知られるようになった.プルマン会社の鉄道ストライキ [94] ,ペンシルヴェニア州スクラントンの炭鉱ストライキ [1902] にはオールトゲルド,デブズを助け,弁護士として活動した.

〖主著〗Wealth against commonwealth, 1894.A country without strikers, 1900.A sovereign people, 1907.Lords of industry, 1910.」

- 「ステフェンズ Steffens, Joseph Lincoln 1866.4.6~1936.8.9

アメリカのジャーナリスト.

《McClure's Magazine》誌 [1901-06] ,《The American Magazine》誌および《Everybody's Magazine》誌 [06-11] の編集に当たり,代表的なマクレイカーとしてセントルイスやミネアポリス,シカゴ,ニューヨーク等の大都市の市政腐敗の暴露その他に峻烈な筆を振るった.10年代以降は世界各地の革命運動に関心を寄せ,メキシコやロシアの政変を好意的に報じた.

〖主著〗The shame of the cities, 1904.The struggle for self-government, 1906.Autobiography of Lincoln Steffens, 2巻, 1931.」

- 「ターベル Tarbell, Ida Minerva 1857.11.5~1944.1.6

アメリカの評論家,歴史家.

《McClure's Magazine》誌 [1894-96] ,《American Magazine》誌 [96-1915] の編集者.社会改革の精神からトラストの不正を暴露し,いわゆる〈マクレーカーmuckraker〉の一人としてT.ローズヴェルトの反トラスト政策を支援した.

〖主著〗The life of Abraham Lincoln, 2巻, 1900.The history of the Standard Oil Company, 2巻, 1904.The nationalizing of business 1878-1898, 1936.All in the day's work, 1939.」

日本大百科事典

- 「ステフェンズ

すてふぇんず

Lincoln Steffens

[1866―1936]

アメリカのジャーナリスト。サンフランシスコ出身。ニューヨークで『マクルーアズ』誌などの編集に携わり、20世紀初頭から「マックレーキング(不正暴露)運動」の先頭にたち、当時の政界、実業界の癒着と腐敗を摘発する記事、論文を意欲的に発表。それらは主著『都市の恥辱 (ちじょく) 』(1904)、『自治のための戦い』(1906)に収録される。また『自伝』(1931)は彼の社会思想や当時の革新運動の動向を知るうえで興味深い。

[渡辺利雄]」

- 「ビアード

びあーど

Charles Austin Beard

[1874―1948]

アメリカ史研究の革新主義学派の代表的な歴史家。インディアナ州に生まれる。デポー大学卒業後オックスフォード大学に留学し、帰国してコロンビア大学で博士号を取得した。1917年までコロンビア大学で歴史および政治学を講義したが、第一次世界大戦中の同年コロンビア大学が平和主義者の教授陣を解職したのに抗議して辞職した。翌年社会調査のための新大学設立に参画するとともに、公務員研修学校長となり、ニューヨーク市の市政調査にも参加した。1922年(大正11)および関東大震災後の翌23年の二度にわたって来日し、東京の市政調査や震災復興計画に協力した。26年にアメリカ政治学会会長に就任し、33年にはアメリカ歴史学会会長を務めた。

学問的にはきわめて多産な研究活動を行い生涯34冊の著作を著したが、現実の政治問題に対しても鋭い政治感覚を有していた。彼が歴史家としての名声を獲得するに至ったのは、1913年に『合衆国憲法の一経済的解釈』を発表したことによってである。この本で彼は、合衆国憲法の制定を推進した「建国の父祖たち」の経済的利害を解明して、アメリカ史における経済的利害の働きの重要性を指摘したが、マクレーカーズとよばれるジャーナリストが種々な社会問題の存在を白日の下にさらし改革運動が進められていた革新主義の時代にあって、彼の見解は、それまで神聖視されてきた合衆国憲法および「建国の父祖たち」を汚すものと受け取られ、学界に賛否両論の大きな波紋を投げかけたのであった。

経済的利害を重視する観点から、ほかに『ジェファソン民主主義の経済的起源』(1915)や『政治の経済的基礎』(1922)などを著したが、しだいに観念の働きにも関心を抱くに至った。最後の著作『ルーズベルトと第二次世界大戦』(1947)では、参戦するために日本の真珠湾攻撃を誘発したとしてルーズベルト大統領の開戦決定を厳しく批判している。

[五十嵐武士]」

- 「フィリップス

ふぃりっぷす

David Graham Phillips

[1867―1911]

アメリカの小説家。プリンストン大学卒業。ジャーナリストとして活動後、異常者に殺されるまでの10年間に23冊の小説を書いた。20世紀初頭に、大統領T・ルーズベルトが主唱しておこったマックレーキング(社会悪暴露)運動に投じた作家の一人で、政財界の腐敗、婦人問題に取材した、『偉大なる神の成功』(1901)、『洪水』(1905)、『二代目』(1907)、『スーザン・リノックス』(1917)などの問題作がある。

[稲澤秀夫]」

世界文学大辞典

- 「マックレイカーズ

[英]muckrakers

北米

20世紀初頭アメリカで政財界の腐敗を暴露する小説やノンフィクションを書いた一群の作家に,シオドア・ローズヴェルト大統領が与えた呼び名。「マックリュアズ・マガジン」「コリアーズ」などの雑誌を主な舞台にして活躍し,著作による社会改革をめざした。U.シンクレアの『ジャングル』が食肉産業の不潔を暴露して食品管理法成立を促したのはよく知られた例。主な作家としてリンカン・ステファンズ,デイヴィッド・グラハム・フィリップス,アイダ・ターベルなど。

(村山淳彦)」

- 「シンクレア アプトン

Upton Beall Sinclair

北米 1878.9.20-1968.11.25

アメリカの作家。南部の名家の出身ながら落ちぶれた父と,裕福な家庭出身の母のあいだに一人息子としてボルティモアで生まれ,ニューヨークで育った。ニューヨーク市立大学在学中から学資かせぎに売文をしていたが,コロンビア大学大学院在学中シェリーの詩に啓発されて本格的な文筆活動を始め,理想主義的な小説を書くようになった。南北戦争をあつかった歴史小説『マナサス』Manassas(1904)を書いたころに社会主義と出合い,いわゆるマックレイカーズの一員として,政治・経済・社会の諸問題をフィクションの形で,あるいはノンフィクションの形で精力的に書き続けた。他方,社会党員(のちに民主党員)として社会運動にも熱心に参加し,1930年代にはカリフォルニアでEPICと称する社会改良運動を基礎に何度も公職選挙に立候補した。

シンクレアは長命な生涯を通じて膨大な量の著作を残したが,審美的観点からだけでは評価できない。主な小説作品としては,シカゴ精肉業に働く移民の苛酷(かこく)な労働条件と,非衛生的な工程を暴露して一大センセーションを巻きおこした『ジャングル』The Jungle(06)をはじめとして,『石炭王』King Coal(17),『石油!』Oil!(27),サッコ=ヴァンゼッティ事件をあつかった『ボストン』Boston(28)などのほか,『世界の終わり』World's End(40)を第1作として全11巻からなる連作小説《ラニー・バッド・シリーズ》Lanny Budd Series(40−53)がある。ジャーナリズムの実態をあばいた『真鍮(しんちゆう)の貞操帯』The Brass Check(19)や,芸術,文学の商業主義を突く『拝金芸術』Mammonart(25)など,ノンフィクションも多数。第二次大戦前は日本でも翻訳でよく読まれ,有名だった。

(村山淳彦)」

- 「「マックリュアズ・マガジン」

[英]McClure's Magazine

北米

アメリカの月刊雑誌。1893年サミュエル・シドニー・マックリュアが時事問題と英米著名作家の紹介を目的にニューヨークで創刊。アイダ・ターベルやリンカン・ステファンズの評論を載せ,マックレイカーズの代表的雑誌となったが,社会改革の気運の衰退により1929年廃刊。キャザーが編集者だったこともある。

(井上謙治)

The muckrakers were reform-minded journalists in the Progressive Era in the United States (1890s–1920s) who exposed established institutions and leaders as corrupt. They typically had large audiences in popular magazines. The modern term generally references investigative journalism or watchdog journalism; investigative journalists in the US are often informally called "muckrakers".

The muckrakers played a highly visible role during the Progressive Era.[1] Muckraking magazines—notably McClure's of the publisher S. S. McClure—took on corporate monopolies and political machines, while trying to raise public awareness and anger at urban poverty, unsafe working conditions, prostitution, and child labor.[2] Most of the muckrakers wrote nonfiction, but fictional exposés often had a major impact, too, such as those by Upton Sinclair.[3]

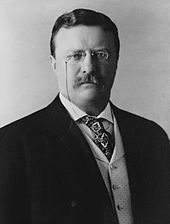

In contemporary American usage, the term can refer to journalists or others who "dig deep for the facts" or, when used pejoratively, those who seek to cause scandal.[4][5] The term is a reference to a character in John Bunyan's classic Pilgrim's Progress, "the Man with the Muck-rake", who rejected salvation to focus on filth. It became popular after President Theodore Roosevelt referred to the character in a 1906 speech; Roosevelt acknowledged that "the men with the muck rakes are often indispensable to the well being of society; but only if they know when to stop raking the muck."[4]

History

[編集]While a literature of reform had already appeared by the mid-19th century, the kind of reporting that would come to be called "muckraking" began to appear around 1900.[6] By the 1900s, magazines such as Collier's Weekly, Munsey's Magazine and McClure's Magazine were already in wide circulation and read avidly by the growing middle class.[7][8] The January 1903 issue of McClure's is considered to be the official beginning of muckraking journalism,[9] although the muckrakers would get their label later. Ida M. Tarbell ("The History of Standard Oil"), Lincoln Steffens ("The Shame of the Cities") and Ray Stannard Baker ("The Right to Work"), simultaneously published famous works in that single issue. Claude H. Wetmore and Lincoln Steffens' previous article "Tweed Days in St. Louis" in McClure's October 1902 issue was called the first muckraking article.

Changes in journalism prior to 1903

[編集]

The muckrakers would become known for their investigative journalism, evolving from the eras of "personal journalism"—a term historians Emery and Emery used in The Press and America (6th ed.) to describe the 19th century newspapers that were steered by strong leaders with an editorial voice (p. 173)—and yellow journalism.

One of the biggest urban scandals of the post-Civil War era was the corruption and bribery case of Tammany boss William M. Tweed in 1871 that was uncovered by newspapers. In his first muckraking article "Tweed Days in St. Louis", Lincoln Steffens exposed the graft, a system of political corruption, that was ingrained in St. Louis. While some muckrakers had already worked for reform newspapers of the personal journalism variety, such as Steffens who was a reporter for the New York Evening Post under Edwin Lawrence Godkin,[10] other muckrakers had worked for yellow journals before moving on to magazines around 1900, such as Charles Edward Russell who was a journalist and editor of Joseph Pulitzer's New York World.[11] Publishers of yellow journals, such as Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst, were more intent on increasing circulation through scandal, crime, entertainment and sensationalism.[12]

Just as the muckrakers became well known for their crusades, journalists from the eras of "personal journalism" and "yellow journalism" had gained fame through their investigative articles, including articles that exposed wrongdoing. Note that in yellow journalism, the idea was to stir up the public with sensationalism, and thus sell more papers. If, in the process, a social wrong was exposed that the average man could get indignant about, that was fine, but it was not the intent (to correct social wrongs) as it was with true investigative journalists and muckrakers.

Julius Chambers of the New York Tribune, could be considered to be the original muckraker. Chambers undertook a journalistic investigation of Bloomingdale Asylum in 1872, having himself committed with the help of some of his friends and his newspaper's city editor. His intent was to obtain information about alleged abuse of inmates. When articles and accounts of the experience were published in the Tribune, it led to the release of twelve patients who were not mentally ill, a reorganization of the staff and administration of the institution and, eventually, to a change in the lunacy laws.[13] This later led to the publication of the book A Mad World and Its Inhabitants (1876). From this time onward, Chambers was frequently invited to speak on the rights of the mentally ill and the need for proper facilities for their accommodation, care and treatment.[14]

Nellie Bly, another yellow journalist, used the undercover technique of investigation in reporting Ten Days in a Mad-House, her 1887 exposé on patient abuse at Bellevue Mental Hospital, first published as a series of articles in The World newspaper and then as a book.[15] Nellie would go on to write more articles on corrupt politicians, sweat-shop working conditions and other societal injustices.

Other works that predate the muckrakers

[編集]- Helen Hunt Jackson (1831–1885) –A Century of Dishonor, U.S. policy regarding Native Americans.

- Henry Demarest Lloyd (1847–1903) – Wealth Against Commonwealth, exposed the corruption within the Standard Oil Company.

- Ida B. Wells (1862–1931) – an author of a series of articles concerning Jim Crow laws and the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad in 1884, and co-owned the newspaper The Free Speech in Memphis in which she began an anti-lynching campaign.

- Ambrose Bierce (1842–1913(?)) – author of a long-running series of articles published from 1883 through 1896 in The Wasp and the San Francisco Examiner attacking the Big Four and the Central Pacific Railroad for political corruption.

- B. O. Flower (1858–1918) – author of articles in The Arena from 1889 through 1909 advocating for prison reform and prohibition of alcohol.

The muckrakers appeared at a moment when journalism was undergoing changes in style and practice.[要出典] In response to yellow journalism, which had exaggerated facts, objective journalism, as exemplified by The New York Times under Adolph Ochs after 1896, turned away from sensationalism and reported facts with the intention of being impartial and a newspaper of record.[16] The growth of wire services had also contributed to the spread of the objective reporting style. Muckraking publishers like Samuel S. McClure, also emphasized factual reporting,[17] but he also wanted what historian Michael Schudson had identified as one of the preferred qualities of journalism at the time, namely, the mixture of "reliability and sparkle" to interest a mass audience.[18] In contrast with objective reporting, the journalists, whom Roosevelt dubbed "muckrakers", saw themselves primarily as reformers and were politically engaged.[19] Journalists of the previous eras were not linked to a single political, populist movement as the muckrakers were associated with Progressive reforms. While the muckrakers continued the investigative exposures and sensational traditions of yellow journalism, they wrote to change society. Their work reached a mass audience as circulation figures of the magazines rose on account of visibility and public interest.[要出典]

Magazines

[編集]

Magazines were the leading outlets for muckraking journalism. Samuel S. McClure and John Sanborn Phillips started McClure's Magazine in May 1893. McClure led the magazine industry by cutting the price of an issue to 15 cents, attracting advertisers, giving audiences illustrations and well-written content and then raising ad rates after increased sales, with Munsey's and Cosmopolitan following suit.[20]

McClure sought out and hired talented writers, like the then unknown Ida M. Tarbell or the seasoned journalist and editor Lincoln Steffens. The magazine's pool of writers were associated with the muckraker movement, such as Ray Stannard Baker, Burton J. Hendrick, George Kennan (explorer), John Moody (financial analyst), Henry Reuterdahl, George Kibbe Turner, and Judson C. Welliver, and their names adorned the front covers. The other magazines associated with muckraking journalism were American Magazine (Lincoln Steffens), Arena (G. W. Galvin and John Moody), Collier's Weekly (Samuel Hopkins Adams, C.P. Connolly, L. R. Glavis, Will Irwin, J. M. Oskison, Upton Sinclair), Cosmopolitan (Josiah Flynt, Alfred Henry Lewis, Jack London, Charles P. Norcross, Charles Edward Russell), Everybody's Magazine (William Hard, Thomas William Lawson, Benjamin B. Lindsey, Frank Norris, David Graham Phillips, Charles Edward Russell, Upton Sinclair, Lincoln Steffens, Merrill A. Teague, Bessie and Marie Van Vorst), Hampton's (Rheta Childe Dorr, Benjamin B. Hampton, John L. Mathews, Charles Edward Russell, and Judson C. Welliver), The Independent (George Walbridge Perkins, Sr.), Outlook (William Hard), Pearson's Magazine (Alfred Henry Lewis, Charles Edward Russell), Twentieth Century (George French), and World's Work (C.M. Keys and Q.P.).[21] Other titles of interest include Chatauquan, Dial, St. Nicholas. In addition, Theodore Roosevelt wrote for Scribner's Magazine after leaving office.

Origin of the term, Theodore Roosevelt

[編集]

After President Theodore Roosevelt took office in 1901, he began to manage the press corps. To do so, he elevated his press secretary to cabinet status and initiated press conferences. The muckraking journalists who emerged around 1900, like Lincoln Steffens, were not as easy for Roosevelt to manage as the objective journalists, and the President gave Steffens access to the White House and interviews to steer stories his way.[22][23]

Roosevelt used the press very effectively to promote discussion and support for his Square Deal policies among his base in the middle-class electorate. When journalists went after different topics, he complained about their wallowing in the mud.[24] In a speech on April 14, 1906 on the occasion of dedicating the House of Representatives office building, he drew on a character from John Bunyan's 1678 classic, Pilgrim's Progress, saying:

...you may recall the description of the Man with the Muck-rake, the man who could look no way but downward with the muck-rake in his hands; who was offered a celestial crown for his muck-rake, but who would neither look up nor regard the crown he was offered, but continued to rake to himself the filth of the floor.[25]

While cautioning about possible pitfalls of keeping one's attention ever trained downward, "on the muck", Roosevelt emphasized the social benefit of investigative muckraking reporting, saying:

There are, in the body politic, economic and social, many and grave evils, and there is urgent necessity for the sternest war upon them. There should be relentless exposure of and attack upon every evil man whether politician or business man, every evil practice, whether in politics, in business, or in social life. I hail as a benefactor every writer or speaker, every man who, on the platform, or in book, magazine, or newspaper, with merciless severity makes such attack, provided always that he in his turn remembers that the attack is of use only if it is absolutely truthful.

Most of these journalists detested being called muckrakers. They felt betrayed that Roosevelt would coin them with such a term after they had helped him with his election. Muckraker David Graham Philips believed that the tag of muckraker brought about the end of the movement as it was easier to group and attack the journalists.[26]

The term eventually came to be used in reference to investigative journalists[要出典] who reported about and exposed such issues as crime, fraud, waste, public health and safety, graft, illegal financial practices. A muckraker's reporting may span businesses and government.

Early 20th century muckraking

[編集]- Early Writers of the Muckraking Tradition

-

Mark Sullivan with his secretary, Mabel Shea

Some of the key documents that came to define the work of the muckrakers were:

Ray Stannard Baker published "The Right to Work" in McClure's Magazine in 1903, about coal mine conditions, a coal strike, and the situation of non-striking workers (or scabs). Many of the non-striking workers had no special training or knowledge in mining, since they were simply farmers looking for work. His investigative work portrayed the dangerous conditions in which these people worked in the mines, and the dangers they faced from union members who did not want them to work.

Lincoln Steffens published "Tweed Days in St. Louis", in which he profiled corrupt leaders in St. Louis, in October 1902, in McClure's Magazine.[27] The prominence of the article helped lawyer Joseph Folk to lead an investigation of the corrupt political ring in St. Louis.

Ida Tarbell published The Rise of the Standard Oil Company in 1902, providing insight into the manipulation of trusts. One trust they manipulated was with Christopher Dunn Co. She followed that work with The History of The Standard Oil Company: the Oil War of 1872, which appeared in McClure's Magazine in 1908. She condemned Rockefeller's immoral and ruthless business tactics and emphasized "our national life is on every side distinctly poorer, uglier, meaner, for the kind of influence he exercises." Her book generated enough public anger that it led to the splitting up of Standard Oil under the Sherman Anti Trust Act.[28]

Upton Sinclair published The Jungle in 1906, which revealed conditions in the meat packing industry in the United States and was a major factor in the establishment of the Pure Food and Drug Act and Meat Inspection Act.[29] Sinclair wrote the book with the intent of addressing unsafe working conditions in that industry, not food safety.[29] Sinclair was not a professional journalist but his story was first serialized before being published in book form. Sinclair considered himself to be a muckraker.

"The Treason of the Senate: Aldrich, the Head of it All", by David Graham Phillips, published as a series of articles in Cosmopolitan magazine in February 1906, described corruption in the U.S. Senate. This work was a keystone in the creation of the Seventeenth Amendment which established the election of Senators through popular vote.

The Great American Fraud (1905) by Samuel Hopkins Adams revealed fraudulent claims and endorsements of patent medicines in America. This article shed light on the many false claims that pharmaceutical companies and other manufacturers would make as to the potency of their medicines, drugs and tonics. This exposure contributed heavily to the creation of the Pure Food and Drug Act alongside Upton Sinclair's work. Using the example of Peruna in his article, Adams described how this tonic, which was made of seven compound drugs and alcohol,[30] did not have "any great potency".[30] Manufacturers sold it at an obscene price and hence made immense profits. His work forced a crackdown on a number of other patents and fraudulent schemes of medicinal companies.

Many other works by muckrakers brought to light a variety of issues in America during the Progressive era.[30] These writers focused on a wide range of issues including the monopoly of Standard Oil; cattle processing and meat packing; patent medicines; child labor; and wages, labor, and working conditions in industry and agriculture. In a number of instances, the revelations of muckraking journalists led to public outcry, governmental and legal investigations, and, in some cases, legislation was enacted to address the issues the writers' identified, such as harmful social conditions; pollution; food and product safety standards; sexual harassment; unfair labor practices; fraud; and other matters. The work of the muckrakers in the early years, and those today, span a wide array of legal, social, ethical and public policy concerns.

Muckrakers and their works

[編集]- Samuel Hopkins Adams (1871–1958) – The Great American Fraud (1905), exposed false claims about patent medicines.

- Paul Y. Anderson (August 29, 1893 – December 6, 1938) is best known for his reporting of a race riot and the Teapot Dome scandal.

- Ray Stannard Baker (1870–1946) – of McClure's & The American Magazine.

- Louis D. Brandeis (1856–1941) – published his combined findings of the monopolies of big banks and big business in his 1914 book Other People's Money And How the Bankers Use It. Subsequently, appointed to the Supreme Court (1916).

- Marion Hamilton Carter (1865-1937) - "Pellagra" and "The Vampire of the South" 1909 McClure's.

- Burton J. Hendrick (1870–1949) – "The Story of Life Insurance" May – November 1906 McClure's.

- Frances Kellor (1873–1952) – studied chronic unemployment in her book Out of Work (1904).

- Thomas William Lawson (1857–1924) Frenzied Finance (1906) on Amalgamated Copper stock scandal.

- Edwin Markham (1852–1940) – published an exposé of child labor in Children in Bondage (1914).

- Gustavus Myers (1872–1942) – documented corruption in his first book "The History of Tammany Hall" (1901) unpublished, Revised edition, Boni and Liveright, 1917. His second book (in three volumes) related a "History of the Great American Fortunes" Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Co., 1909–10; Single volume Modern Library edition, New York, 1936. Other works include "History of The Supreme Court of the United States" Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Co., 1912. "A History of Canadian Wealth" Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Co., 1914. "History of Bigotry in the United States" New York: Random House, 1943 Published posthumously.

- Frank Norris (1870–1902) The Octopus.

- Fremont Older (1856–1935) – wrote on San Francisco corruption and on the case of Tom Mooney.

- Drew Pearson (1897–1969) – wrote syndicated newspaper column "Washington Merry-Go-Round".

- Jacob Riis (1849–1914) – How the Other Half Lives, the slums.

- Charles Edward Russell (1860–1941) – investigated Beef Trust, Georgia's prison.

- Upton Sinclair (1878–1968) – The Jungle (1906), US meat-packing industry, and the books in the "Dead Hand" series that critique the institutions (journalism, education, etc.) that could but did not prevent these abuses.

- John Spargo (1876–1966) – American reformer and author, The Bitter Cry of Children (child labor).

- Lincoln Steffens (1866–1936) The Shame of the Cities (1904) – uncovered the corruption of several political machines in major cities.

- Ida M. Tarbell (1857–1944) exposé, The History of the Standard Oil Company.

- John Kenneth Turner (1879–1948) – author of Barbarous Mexico (1910), an account of the exploitative debt-peonage system used in Mexico under Porfirio Díaz.

- Ida B. Wells (1862–1931) – The Free Speech (1892) condemned the flaws in the United States justice system that allowed lynching to happen.[31][32]

Disappearance

[編集]The influence of the muckrakers began to fade during the more conservative presidency of William Howard Taft. Corporations and political leaders were also more successful in silencing these journalists as advertiser boycotts forced some magazines to go bankrupt. Through their exposés, the nation was changed by reforms in cities, business, politics, and more. Monopolies such as Standard Oil were broken up and political machines fell apart; the problems uncovered by muckrakers were resolved and thus the muckrakers of that era were needed no longer.[33]

Impact

[編集]According to Fred J. Cook, the muckrakers' journalism resulted in litigation or legislation that had a lasting impact, such as the end of Standard Oil's monopoly over the oil industry, the establishment of the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, the creation of the first child labor laws in the United States around 1916. Their reports exposed bribery and corruption at the city and state level, as well as in Congress, that led to reforms and changes in election results.

"The effect on the soul of the nation was profound. It can hardly be considered an accident that the heyday of the muckrakers coincided with one of America's most yeasty and vigorous periods of ferment. The people of the country were aroused by the corruptions and wrongs of the age – and it was the muckrakers who informed and aroused them. The results showed in the great wave of progressivism and reform cresting in the remarkable spate of legislation that marked the first administration of Woodrow Wilson from 1913 to 1917. For this, the muckrakers had paved the way."[34]

Other changes that resulted from muckraker articles include the reorganization of the U.S. Navy (after Henry Reuterdahl published a controversial article in McClure's). Muckraking investigations were used to change the way senators were elected by the Seventeenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and led to government agencies to take on watchdog functions.[33]

Since 1945

[編集]Some today use "investigative journalism" as a synonym for muckraking. Carey McWilliams, editor of the Nation, assumed in 1970 that investigative journalism, and reform journalism, or muckraking, were the same type of journalism.[35] Journalism textbooks point out that McClure's muckraking standards, "Have become integral to the character of modern investigative journalism."[36] Furthermore, the successes of the early muckrakers have continued to inspire journalists.[37][38] Moreover, muckraking has become an integral part of journalism in American History. Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein exposed the workings of the Nixon Administration in Watergate which led to Nixon's resignation. More recently, Edward Snowden disclosed the activities of governmental spying, albeit illegally, which gave the public knowledge of the extent of the infringements on their privacy.

See also

[編集]References

[編集]- ^ Filler, Louis (1976). The Muckrakers: New and Enlarged Edition of Crusaders for American Liberalism. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. pp. 361, 367–68, 372. ISBN 0-271-01212-9

- ^ Herbert Shapiro, ed., The muckrakers and American society (Heath, 1968), contains representative samples as well as academic commentary.

- ^ Judson A. Grenier, "Muckraking the muckrakers: Upton Sinclair and his peers." in David R Colburn and Sandra Pozzetta, eds., Reform and Reformers in the Progressive Era (1983) pp: 71–92.

- ^ a b "'Muckraker: 2 Meanings", The New York Times, April 10, 1985.

- ^ Lapsansky-Werner, Emma J. United States History: Modern America, Boston, MA: Pearson Learning Solutions, 2011, p. 102.

- ^ Regier 1957, p. 49.

- ^ American epoch: a history of the United States since the 1890s (1st ed.). New York: Knopf. (1955). p. 62

- ^ Brinkley, Alan. “Chapter 21: Rise of Progressivism”. In Barrosse, Emily. American History, A Survey (twelfth ed.). Los Angeles, CA, US: McGraw Hill. pp. 566–67. ISBN 978-0-07-325718-1

- ^ Weinberg & Weinberg 1964, p. 2.

- ^ Steffens, Lincoln (1958). The Autobiography of Lincoln Steffens, abridged. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World. p. 145

- ^ Cook, Fred J. (1972). The Muckrakers: Crusading Journalists who Changed America. Garden City, New York: Doubleday. pp. 131

- ^ “Crucible Of Empire : The Spanish–American War – PBS Online”. Pbs.org. December 7, 2013時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。January 4, 2014閲覧。

- ^ "A New Hospital for the Insane" (Dec. 1876) Brooklyn Daily Eagle

- ^ “An Insane Hospital for Brooklyn” (December 23, 1876). January 4, 2014閲覧。

- ^ “Nellie Bly”. Biography. May 2, 2018閲覧。

- ^ Walker, Martin (1983). Powers of the Press: Twelve of the World's Influential Newspapers. New York: Adama Books. pp. 215–217. ISBN 0-915361-10-8

- ^ Weinberg, p. 2

- ^ Schudson, Michael (1978). Discovering the News: A Social History of American Newspapers. New York: BasicBooks. p. 79

- ^ Chalmers, David Mark (1964). The Social and Political Ideas of Muckrakers. New York: Citadel Press. pp. 105–08

- ^ Wilson, p. 63

- ^ Weinberg, p. 441-443

- ^ Rivers, William L (1970). The Adversaries: Politics and the Press. Boston: Beacon Press. pp. 16–20

- ^ Steffens 1958, pp. 347–59.

- ^ Stephen E. Lucas, "Theodore Roosevelt's 'the man with the muck‐rake': A reinterpretation." Quarterly Journal of Speech 59#4 (1973): 452–462.

- ^ a b Roosevelt, Theodore (1958). Andrews, Wayne. ed. The Autobiography, Condensed from the Original Edition, Supplemented by Letters, Speeches, and Other Writings (1st ed.). New York City: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 246–47

- ^ SpartacusEducational.com. "Muckraking Journalism." (1997) Spartacus Educational. “Archived copy”. May 7, 2017時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2017年5月18日閲覧。. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- ^ Gallagher 2006, p. 13.

- ^ smithosonianmag.com "The Woman Who Took On a Tycoon." http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-woman-who-took-on-the-tycoon-651396/. Retrieved May 17, 2017.

- ^ a b Ushistory.org. "Muckrakers." (2014). U.S. History Online Textbook. http://www.ushistory.org/us/42b.asp. Retrieved January 21, 2014.

- ^ a b c Weinberg, p. 195

- ^ Lee D. Baker. "Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Her Passion for Justice." (1996) Duke University. “Archived copy”. May 8, 2017時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2017年5月18日閲覧。. Retrieved May 17, 2017.

- ^ Biography.com. "Ida B. Wells." (2017) Biography. “Archived copy”. February 23, 2017時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2017年2月17日閲覧。. Retrieved May 17, 2017.

- ^ a b Daly, Christopher (2012). Covering America : a narrative history of a nation's journalism. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 147–148. ISBN 978-1-55849-911-9. OCLC 793012714

- ^ Cook, Fred J. (1972). The Muckrakers: Crusading Journalists who Changed America. Garden City, New York: Doubleday. pp. 179

- ^ James L. Aucoin, The Evolution of American Investigative Journalism (University of Missouri Press, 2007) p. 90.

- ^ W. David Sloan; Lisa Mullikin Parcell (2002). American Journalism: History, Principles, Practices. McFarland. pp. 211–213. ISBN 9780786413713.

- ^ Cecelia Tichi, Exposés and excess: Muckraking in America, 1900/2000 (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013)

- ^ Stephen Hess, Whatever Happened to the Washington Reporters, 1978–2012 (2012)

Bibliography

[編集]- Applegate, Edd. Muckrakers: A Biographical Dictionary of Writers and Editors (Scarecrow Press, 2008); 50 entries, mostly American contents

- Cook, Fred J (1972), The Muckrakers, Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Co.

- Gallagher, Aileen (2006), The Muckrakers, American Journalism During the Age of Reform, New York: The Rosen Publishing Group.

- Lucas, Stephen E. "Theodore Roosevelt's 'the man with the muck‐rake': A reinterpretation." Quarterly Journal of Speech 59#4 (1973): 452–462.

- Regier, CC (1957), The Era of the Muckrakers, Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith.

- Steffens, Lincoln (1958), The Autobiography of Lincoln Steffens (abridged ed.), New York: Harcourt, Brace & World

- Swados, Harvey, ed. (1962), Years of Conscience: The Muckrakers, Cleveland: World Publishing Co.

- Weinberg, Arthur; Weinberg, Lila, eds. (1964), The Muckrackers: The Era in Journalism that Moved America to Reform, the Most Significant Magazine Articles of 1902–1912, New York: Capricon Books.

- Wilson, Harold S. (1970). McClure's Magazine and the Muckrakers. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 069104600X.

マックレーカー

マックレーカー(英語: Muckraker)とは、アメリカ合衆国の革新主義時代(1890年代から1920年代)における改革志向のジャーナリストであり、既存の体制や指導者を腐敗したものとして晒しあげた人々のことである。通常、人気のある雑誌で多くの読者がいることが多かった。現代における用語としては、一般的に調査報道またはウォッチ・ドッグ(番犬)ジャーナリズムのことを指し、アメリカにおいて調査報道を行うジャーナリストはしばしば俗に「マックレーカー」と呼ばれることがある。

概要

[編集]マックレーカーは革新主義時代に非常に顕著な役割を果たした[1]。マックレーカーによる雑誌、特にサミュエル・S・マクルーアによる『マクルーア・マガジン』は企業の独占とマシーン政治に挑む一方で、都市の貧困や危険な労働環境、売春、そして児童労働に対しての大衆の問題意識や怒りを高めようとした[2]。ほとんどのマックレーカーたちはノンフィクションとして記事を書いたが、アプトン・シンクレアが書いたもののようにフィクションの形をとった暴露記事もまた大きな影響を与えた[3]。

現代のアメリカにおける用法では、この用語は「事実に向かって深く掘り下げる」ジャーナリストなどの人々を指し、また侮蔑的に使われる場合ではスキャンダルを引き起こそうとする人々を指すことがある[4][5]。この言葉はジョン・バニヤンの古典、『天路歴程』の登場人物である、汚物に集中するあまり救済を断った「肥やし熊手をもった男」に由来するものであり、セオドア・ルーズベルト大統領が1906年の演説でその男に言及した後に一般的な言葉となった。ルーズベルトは「肥やし熊手を持った男は大抵社会が良い状態であることにとって不可欠であるが、ただしそれは彼らがかき集めることをやめる時期を知っている場合に限る」と認めた[4]。

歴史

[編集]革新主義的な著述は19世紀半ばまでにすでに登場していたが、「マックレーキング」と呼ばれるような種類の報道は1900年頃に登場し始めた[6]。1900年代までに『コリアーズ・ウィークリー』や『マンジーズ・マガジン』、『マクルーア・マガジン』はすでに広く流通しており、増えつつあった中流階級の人々に熱心に読まれていた[7][8]。『マクルーア・マガジン』の1903年1月号がマックレーキング・ジャーナリズムの本格的な始まりであると考えられているが[9]、実際にマックレーカーたちが認識されるのはもう少し後のことであった。イーダ・ターベル(「スタンダード石油会社の歴史」)、リンカン・ステファンズ(「都市の恥辱」)、レイ・スタンナード・ベイカー(「労働の権利」)がその一号で有名な作品を同時に出版したのである。クロード・H・ウェットモアとリンカン・ステファンズの『マクルーア・マガジン』1902年10月号に掲載されたそれ以前の記事、「"Tweed Days in St. Louis"」が最初のマックレーキング記事と呼ばれていた。

1903年以前のジャーナリズムの変化

[編集]「パーソナル・ジャーナリズム」とイエロー・ジャーナリズムの時代から発展し、マックレーカーたちは調査報道で知られるようになる。なおこの「パーソナル・ジャーナリズム」という言葉は、歴史家のエドウィン・エメリーとマイケル・エメリーが『アメリカ報道史』で、強力な編集者の意見で舵取りがなされた19世紀の新聞の様子を表現するために用いた用語である[10]。

南北戦争後の最大の都市のスキャンダルの1つは、新聞報道によって明るみに出た、タマニー・ホールの会長ウィリアム・M・トゥイードの1871年の汚職と賄賂事件だった。リンカン・ステファンズは最初のマックレーキング記事「"Tweed Days in St. Louis"」で、セントルイスに根付いた政治腐敗システムである収賄(graft)を暴露した。ステファンズがエドウィン・ローレンス・ゴッドキンの下でニューヨーク・イブニング・ポストの記者を勤めたように、一部のマックレーカーたちがパーソナル・バラエティの一種である革新派の新聞に勤めている一方で[11]、チャールズ・エドワード・ラッセルがジョーゼフ・ピュリッツァーの『ニューヨーク・ワールド』紙に記者及び編集者として勤めたように、その他のマックレーカーたちは1900年ごろに雑誌に移るまではイエロー・ペーパーに勤めた[12]。ジョーゼフ・ピュリッツァーやウィリアム・ランドルフ・ハーストなどのイエロー・ジャーナリズム的な発行者はスキャンダルや犯罪、娯楽、扇情主義によって部数を増やすことに熱心であった[13]。

マックレーカーが「聖戦」で有名になったのと同じように、パーソナル・ジャーナリズムとイエロー・ジャーナリズムの時代のジャーナリストは、不正を暴露した記事を含む調査報道を通じて名声を得ていた。なおイエロー・ジャーナリズムにおいては、その理念は扇情主義によって大衆を奮い立たせ、それによってより多くの部数を売るところにあったということに注意すべきである。その過程で仮に普通の人々が憤慨するであろう社会的不正が露呈したとしても、それは特に問題のないことではあったが、そこに真の調査報道ジャーナリストやマックレーカーたちのように社会的な不正を正す意図はなかった。

『ニューヨーク・トリビューン』紙のジュリアス・チェンバーズは、元祖マックレーカーと見なすことができる。チェンバースは1872年にブルーミングデール精神病院における調査報道に着手し、数人の友人と市の編集者の助けを借りて取り組んだ。彼の目的は、収容者に対する虐待の疑いに関して情報を入手することであった。体験の報告と記事と説明が『ニューヨーク・トリビューン』紙に掲載され、それは精神病患者ではなかった12人の患者の解放、スタッフの再編成と施設の管理、そして最終的には精神異常者に対する法律の改正へとつながった[14]。これは後に書籍『"A Mad World and its Inhabitants" 』(1876)として出版された。この時以来、チェンバーズは精神障害者の権利と彼らのための宿泊施設、ケアや治療に適した施設の必要性について話すようにゲストスピーカーとして頻繁に招かれた[15]。

また別のイエロー・ジャーナルストであるネリー・ブライは潜入調査を行って『精神病院での10日間』という本で報告した。これはベルビュー精神病院における患者虐待に関する1887年の暴露記事で、当初は『ワールド』紙の連載記事として発行されたが、のちに書籍化された[16]。ネリーは腐敗した政治家や搾取工場の労働環境、またその他の社会的不正についてもさらに記事を書き続けた。

マックレーキングの時代より前の作品

[編集]- ヘレン・ハント・ジャクソン(1831–1885)– 「"A Century of Dishonor"」でネイティブアメリカンに関するアメリカの政策を報じた。

- ヘンリー・デマレスト・ロイド(1847–1903)– 「"Wealth Against Commonwealth"」でスタンダード・オイルの汚職を暴露した

- アイダ・B・ウェルズ(1862–1931)– ジム・クロウ法とチェサピーク・アンド・オハイオ鉄道に関する1884年の一連の記事を書いた。また反リンチキャンペーンを始める場となったメンフィスの新聞『The FreeSpeech』紙の共同所有者になった。

- アンブローズ・ビアス(1842–1913(?))– セントラル・パシフィック鉄道をめぐる政治腐敗を批判する記事を『ワスプ』紙と『サンフランシスコ・エグザミナー』紙に1883年から1896年に渡って長期連載した。

- B・O・フラワー(1858–1918)– 刑務所改革とアルコール禁止を提唱する記事を、『The Arena』紙に1889年から1909年まで連載した。

ジャーナリズムが理念と実践において変化を遂げていた時に、マックレーカーは登場した[要出典]。事実を誇張していたイエロージャーナリズムに対して、1896年以降のアドルフ・オックスの下での『ニューヨーク・タイムズ』のような客観報道主義は扇情主義から離れ、公平で記録としての新聞となることを目的に、事実を報道した[17]。通信社の成長もまた、客観報道の普及に貢献した。サミュエル・S・マクルーアのようなマックレーカーの出版社も真実の報道を強調したが[18]、しかしまた一方で、歴史家マイケル・シャドセンが当時のジャーナリズムの好ましい特質の1つとして特定したもの、つまり大勢の読者に興味を持たせるための「信頼性ときらめき(reliability and sparkle)」の混合を望んでいた[19]。客観報道とは対照的に、ルーズベルトが「マックレーカー」と呼んだジャーナリストは自分たちを主に改革者と見なし、政治的に十時するようになっていった[20]。マックレーカーが進歩主義的な改革と結びついていたのとは違って、前の時代のジャーナリストは一つの政治的、大衆的運動に紐づけられていたわけではなかった。マックレーカーは、イエロージャーナリズムの調査報道と扇情主義的な伝統を受け継ぎながら、社会を変えるために書いた。雑誌の発行部数が認知度と公共の利益のために上昇したため、彼らの作品は多くの聴衆に届いた[要出典]。

雑誌はマックレーキング・ジャーナリズムの吐口となった。サミュエル・S・マクルーアとジョン・サンボーン・フィリップスは1893年5月に『マクルーア・マガジン』を創刊した。マクルーアは、1号の価格を15セントに引き下げ、広告主を引き付け、読者にイラストとよく書かれたコンテンツを提供し、売り上げを伸ばした後に広告率を上げる手法で雑誌業界をリードし、『マンジーズ・マガジン』と『コスモポリタン』がそれに続いた[21]。

マクルーアは、当時は知られていなかったイーダ・M・ターベルや、経験豊富なジャーナリスト兼編集者のリンカン・ステファンズなど、才能のある作家を探して雇った。雑誌の作家の予備要員は、レイ・スタンナード・ベイカーやバートン・J・ヘンドリック、ジョージ・ケナン、ジョン・ムーディー、ヘンリー・ロイターダール、ジョージ・キビー・ターナー、ジャドソン・C・ウェリバーなどのマックレーキング運動に関連しており、彼らの名前が表紙を飾っていた。マックレーキング・ジャーナリズムに関わった他の雑誌は、リンカン・ステファンズの『アメリカンマガジン』、G・W・ガルビンとジョン・ムーディーの『アリーナ』、サミュエル・ホプキンス・アダムス、C・P・コノリー、L・R・グレイビス、ウィル・アーウィン、J・M・オスキソン、アプトン・シンクレアらの『コリアーズ・ウィークリー』、コスモポリタン(ジョサイア・フリント、アルフレッド・ヘンリー・ルイス、ジャック・ロンドン、チャールズ・P・ノークロス、チャールズ・エドワード・ラッセルらの『コスモポリタン』、ウィリアム・ハード、トーマス・ウィリアム・ローソン、ベンジャミン・B・リンゼイ、フランク・ノリス、デービッド・グラハム・フィリップス、チャールズ・エドワード・ラッセル、アプトン・シンクレア、リンカン・ステファンズ、メリル・A・ティーグ、べシー・ファン・フォルストとマリー・ファン・フォルストらの『エブリデイズ・マガジン』、レタ・チャイルド・ドア、ベンジャミン・B・ハンプトン、ジョン・L・マシュー、チャールズ・エドワード・ラッセル、ジャドソン・C・ウェリヴァーの『ハンプトンズ』、サー・ジョージ・ウェルブリッジ・パーキンスの『インディペンデント』、ウィリアム・ハードの『アウトルック』、アルフレッド・ヘンリー・ルイス、チャールズ・エドワード・ラッセルの『ピアソンズ・マガジン』、ジョージ・フレンチの『20センチュリー』そしてC・M・キーズの『ワールズ・ワーク』などである[22]。その他の地域内のタイトルはChatauquan、ダイヤル、聖ニコラスが含まれます。さらに、セオドア・ルーズベルトは、退任後に『スクリブナーズ・マガジン』に寄稿しました。

用語の由来とセオドア・ルーズベルト

[編集]セオドア・ルーズベルトが1901年に大統領に就任した後、彼は記者団の管理を始めた。そのため、報道官を閣僚の地位に昇格させ、記者会見を始めた。リンカン・ステファンズのように1900年頃に登場したマックレーキング・ジャーナリストは、ルーズベルトにとって客観報道主義のジャーナリストほど管理するのは容易ではなかったので、思い通りに操るため、ステファンズにホワイトハウスへのアクセスとインタビューの機会を与えた[23][24]。

ルーズベルトはマスコミを非常に効果的に利用して、中産階級有権者の彼の支持基盤の間で「スクエア・ディール」に対する議論と支持を促進した。ジャーナリストがさまざまなトピックを追いかけたとき、彼は泥の中をうろついていることについて不平を言いました[25]。1906年4月14日、下院の献納に際してのスピーチでジョン・バニヤンの1678年の古典『天路歴程』から一人の登場人物を引用して述べた。

...you may recall the description of the Man with the Muck-rake, the man who could look no way but downward with the muck-rake in his hands; who was offered a celestial crown for his muck-rake, but who would neither look up nor regard the crown he was offered, but continued to rake to himself the filth of the floor.[26]

ルーズベルトは、注意を下向きに訓練し続けることの潜在的な落とし穴について警告しながら、「泥だらけ」で、調査報道の社会的利益を強調し、次のように述べている。

There are, in the body politic, economic and social, many and grave evils, and there is urgent necessity for the sternest war upon them. There should be relentless exposure of and attack upon every evil man whether politician or business man, every evil practice, whether in politics, in business, or in social life. I hail as a benefactor every writer or speaker, every man who, on the platform, or in book, magazine, or newspaper, with merciless severity makes such attack, provided always that he in his turn remembers that the attack is of use only if it is absolutely truthful.

多くのこういったジャーナリストは、マックレーカーと呼ばれることを忌み嫌っていた。彼らは選挙に際してルーズベルトを助けた後に、ルーズベルトがそのような用語を彼らに対して造ったことについて、裏切られたと感じた。マックレーカーのデイビッド・グラハム・フィリップスは、ジャーナリストを一括りにして批判するのがより簡単になり、マックレーカーのレッテルが運動に終わりをもたらしたと信じていた[27]。

この用語は、最終的に犯罪や詐欺、浪費、公衆衛生や安全、賄賂、違法な金融慣行について調査し、暴露する調査報道を行うジャーナリストに関して使われるようになった[要出典]。マックレーカーの報道は、企業と政府にまたがる可能性もある。

20世紀初頭のマックレーキング

[編集]マックレーカーの仕事をはっきりとさせることになった鍵となる文書は次のとおりである。

レイ・スタンナード・ベイカーは1903年、『マクルーア・マガジン』に「労働の権利」を発表し、炭鉱の状況やストライキ、および非ストライキ労働者(またはスト破り)の状況について説明した。多くのストライキをしていない労働者たちは、ただ単に仕事を探している農民であったため、鉱業に関する特別な訓練経験や知識を持っていなかった。彼の調査報道は、こういった人々が鉱山で働いているという危険な状況と、彼らが彼らに働いてほしくない組合員から直面した危険を描いた。

リンカーン・ステファンズは「セントルイスのツイード・デイズ」を出版し、1902年10月の『マクルーア・マガジン』でセントルイスの腐敗した政治家の輪郭を描いた[28]。この記事が傑出していたおかげで、弁護士ジョセフ・フォークはセントルイスの腐敗した政治家一味の調査を主導することができた。

イーダ・ターベルは、1902年に『スタンダード・オイルの歴史』を出版し、トラストの市場操作に関する知見を与えた。彼らが操ったトラストの1つは、クリストファー・ダン社であった。彼女は1908年に『マクルーア・マガジン』に掲載された「スタンダード・オイルの歴史:1872年の石油戦争」でその仕事を続けた。彼女はロックフェラーの不道徳で冷酷なビジネス戦略を非難し、「私たちの国民生活は、彼が行使する影響力の類のもののために、あらゆる面で明らかに貧しく、醜く、卑劣である」と強調した。彼女の本は大衆の怒り引き起こすのに十分であったため、シャーマン反トラスト法に基づいたスタンダードオイルの分割へとつながった[29]。

アプトン・シンクレアは1906年に『ジャングル』を出版した。これはアメリカの食肉加工業の状況を明らかにしたものであり、純正食品薬品法と食肉検査法の制定の主な要因となった[30]。シンクレアは、食品の安全性ではなく、業界の危険な労働条件に対処することを目的としてこの本を書いた[30]。シンクレアはプロのジャーナリストではなかったが、彼の物語は本の形で出版される前にまず連載された。シンクレアは自分をマックレーカーだと考えていた。

1906年2月に『コスモポリタン』誌に連載記事として掲載されたデビッド・グラハム・フィリップスによる「上院の反逆:アルドリッチ、そのすべての頭」はアメリカ上院の腐敗を描いたものである。この作品は、大衆の投票を通じた上院議員の選挙を確立した合衆国憲法修正第17条作成の要となった。

サミュエル・ホプキンス・アダムスによる1905年の『グレートアメリカン詐欺』1905)は、アメリカにおける特許薬の不正な主張と支持を明らかにしました。この記事は、製薬会社や他のメーカーが自社の医薬品、医薬品、強壮剤の効力に関して行うであろう多くの誤った主張に光を当てています。この暴露は、アプトンシンクレアの仕事と並んで純正食品薬品法の創設に大きく貢献しました。例使用Perunaを彼の記事では、アダムスは7化合物の薬物やアルコールで作られたこのトニック、どのように説明した[31]、「すべての偉大な効力」を持っていませんでした。 [31]製造業者はそれをわいせつな価格で販売したため、莫大な利益を上げました。彼の仕事は、他の多くの特許や医療会社の詐欺的な計画に対する取り締まりを余儀なくされました。

マックレーカーによる他の多くの作品は、進歩主義時代のアメリカのさまざまな問題を明らかにしました。 [32]これらの作家は、スタンダードオイルの独占を含む幅広い問題に焦点を当てました。牛の加工と食肉包装;特許薬;児童労働;産業と農業における賃金、労働、労働条件。多くの場合、マックラーキングジャーナリストの暴露は、国民の抗議、政府および法律の調査につながり、場合によっては、有害な社会的状況など、作家が特定した問題に対処するための法律が制定されました。汚染;食品および製品の安全基準;性的嫌がらせ;不公正な労働慣行;詐欺;およびその他の事項。初期のマックレーカーの仕事、そして今日のマックレーカーの仕事は、法律、社会、倫理、公共政策のさまざまな懸念にまたがっています。

マックレーカー達と彼らの作品

[編集]- サミュエルホプキンスアダムス(1871–1958)–グレートアメリカン詐欺(1905)は、特許医薬品に関する虚偽の主張を暴露しました。

- ポールY.アンダーソン(1893年8月29日-1938年12月6日)は、人種暴動とティーポットドーム事件の報告で最もよく知られています。

- レイ・スタンナード・ベイカー(1870–1946)– McClure's & The AmericanMagazineの。

- Louis D. Brandeis (1856–1941)–大銀行と大企業の独占に関する彼の調査結果を1914年の著書 『 Other People's Money And How the Bankers Use It』に掲載しました。その後、最高裁判所に任命された(1916年)。

- マリオンハミルトンカーター(1865-1937)-「ペラグラ」と「南の吸血鬼」1909年マクルーアの。

- バートンJ.ヘンドリック(1870–1949)–「生命保険の物語」1906年5月– 11月マクルーアの。

- Frances Kellor (1873–1952)–彼女の著書Out of Work (1904)で慢性失業を研究しました。

- トーマス・ウィリアム・ローソン(1857–1924)熱狂的な金融(1906)、合併銅株スキャンダル。

- エドウィン・マーカム(1852–1940)–ボンデージの子供たち(1914)で児童労働の博覧会を発表しました。

- Gustavus Myers (1872–1942)–彼の最初の本「TheHistory of Tammany Hall」(1901)の未発表、改訂版、Boni and Liveright、1917年に汚職を記録。彼の2冊目の本(3巻)は「偉大なアメリカの幸運の歴史」シカゴに関連していました:Charles H. Kerr&Co.、1909–10;単巻現代図書館版、ニューヨーク、1936年。他の作品には、「合衆国最高裁判所の歴史」シカゴ:チャールズH.カーアンドカンパニー、1912年が含まれます。 「カナダの富の歴史」シカゴ:チャールズH.カーアンドカンパニー、1914年。 「米国における偏見の歴史」ニューヨーク:ランダムハウス、1943年死後出版。

- フランク・ノリス(1870–1902)タコ。

- フリーモント古い(1856-1935)は-サンフランシスコの破損にとのケースに書いたトム・ムーニー。

- Drew Pearson (1897–1969)–シンジケート新聞のコラム「WashingtonMerry-Go-Round」を執筆。

- ジェイコブ・リース(1849–1914)–向こう半分の暮らし方、スラム街。

- チャールズエドワードラッセル(1860–1941)–ジョージア州の刑務所であるビーフトラストを調査しました。

- アプトンシンクレア(1878–1968)–ジャングル(1906)、米国の食肉包装業界、およびこれらの虐待を防ぐことはできたが防げなかった機関(ジャーナリズム、教育など)を批判する「デッドハンド」シリーズの本。

- ジョン・スパルゴ(1876–1966)–アメリカの改革者であり作家、 The Bitter Cry of Children (児童労働)。

- リンカーン・ステフェンス(1866–1936)都市の恥(1904)–主要都市のいくつかの政治機械の腐敗を明らかにしました。

- Ida M. Tarbell (1857–1944)exposé、 The History of the Standard OilCompany。

- ジョン・ケネス・ターナー(1879–1948)–バルバラス・メキシコ(1910)の著者、ポルフィリオ・ディアスの下でメキシコで使用された搾取的な債務ペオン制度の説明。

- アイダ・B・ウェルズ(1862–1931)–言論の自由(1892)は、リンチの発生を許した米国の司法制度の欠陥を非難した。 [33] [34]

衰退

[編集]マックレーカーの影響力は、ウィリアム・ハワード・タフトのより保守的な大統領職の間に薄れ始めました。広告主のボイコットにより一部の雑誌が破産したため、企業や政治指導者もこれらのジャーナリストを黙らせることに成功しました。彼らの博覧会を通じて、国は都市、ビジネス、政治などの改革によって変化しました。スタンダードオイルなどの独占は崩壊し、政治機械は崩壊しました。マックレーカーによって発見された問題は解決されたため、その時代のマックレーカーはもはや必要ありませんでした[35]。

影響

[編集]フレッド・J・クックによれば、マックレーカーのジャーナリズムは、スタンダード・オイルの石油産業に対する独占の終焉、1906年の純正食品薬品法の制定など、永続的な影響を及ぼした訴訟または法律をもたらしました。 1916年頃に米国で最初の児童労働法が制定されました。彼らの報告は、市や州レベル、そして議会での贈収賄と汚職を明らかにし、それが選挙結果の改革と変化につながった。

「国民の魂への影響は甚大でした。マックレーカーの全盛期が、アメリカで最も酵母が多く活発な発酵期間の1つと一致したことは偶然とは考えられません。国の人々は、時代の腐敗と過ちに興奮しました–そして、彼らに知らせて、興奮させたのはマックレーカーでした。結果は、1913年から1917年までのウッドロウウィルソンの最初の政権をマークした立法の驚くべき相次ぐ中で進歩主義と改革の頂点の大きな波で示されました。このために、マックレーカーは道を開いた。[36]」

マックレーカーの記事から生じた他の変更には、米海軍の再編成が含まれます(ヘンリーロイターダールがマクルーアで物議を醸した記事を発表した後)。マックラーキングの調査は、米国憲法修正第17条によって上院議員が選出される方法を変更するために使用され、政府機関が監視機能を引き受けるようになりました[37]。

1945年以降

[編集]今日、一部の人々は「調査報道」をマックラーキングの同義語として使用しています。キャリー・マクウィリアムス、国家の編集者は、調査報道、そして改革ジャーナリズム、またはmuckrakingこと、ジャーナリズムの同じタイプだった1970年を想定しました[38]。 ジャーナリズムの教科書は、マクルーアのマックラーキング基準が「現代の調査報道の性格に不可欠になった」と指摘している[39]。 さらに、初期のマックレーカーの成功はジャーナリストを刺激し続けています[40][41]。さらに、マックレーキングはアメリカの歴史におけるジャーナリズムの不可欠な部分になっています。ボブ・ウッドワードとカール・バーンスタインは、ウォーターゲートでのニクソン政権の働きを暴露し、それがニクソンの辞任につながった。最近では、エドワードスノーデンは、違法ではあるが政府のスパイ活動を開示し、プライバシーの侵害の程度を一般に知った。

脚注

[編集]- ^ Filler, Louis (1976). The Muckrakers: New and Enlarged Edition of Crusaders for American Liberalism. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. pp. 361, 367–68, 372. ISBN 0-271-01212-9

- ^ Herbert Shapiro, ed., The muckrakers and American society (Heath, 1968), contains representative samples as well as academic commentary.

- ^ Judson A. Grenier, "Muckraking the muckrakers: Upton Sinclair and his peers." in David R Colburn and Sandra Pozzetta, eds., Reform and Reformers in the Progressive Era (1983) pp: 71–92.

- ^ a b "'Muckraker: 2 Meanings", The New York Times, April 10, 1985.

- ^ Lapsansky-Werner, Emma J. United States History: Modern America, Boston, MA: Pearson Learning Solutions, 2011, p. 102.

- ^ Regier 1957, p. 49.

- ^ American epoch: a history of the United States since the 1890s (1st ed.). New York: Knopf. (1955). p. 62

- ^ Brinkley, Alan. “Chapter 21: Rise of Progressivism”. In Barrosse, Emily. American History, A Survey (twelfth ed.). Los Angeles, CA, US: McGraw Hill. pp. 566–67. ISBN 978-0-07-325718-1

- ^ Weinberg & Weinberg 1964, p. 2.

- ^ Edwin Emery, Michael C. Emery. "The press and America" 6:173

- ^ Steffens, Lincoln (1958). The Autobiography of Lincoln Steffens, abridged. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World. p. 145

- ^ Cook, Fred J. (1972). The Muckrakers: Crusading Journalists who Changed America. Garden City, New York: Doubleday. pp. 131

- ^ “Crucible Of Empire : The Spanish–American War – PBS Online”. Pbs.org. December 7, 2013時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。January 4, 2014閲覧。

- ^ "A New Hospital for the Insane" (Dec. 1876) Brooklyn Daily Eagle

- ^ “An Insane Hospital for Brooklyn” (December 23, 1876). January 4, 2014閲覧。

- ^ “Nellie Bly”. Biography. May 2, 2018閲覧。

- ^ Walker, Martin (1983). Powers of the Press: Twelve of the World's Influential Newspapers. New York: Adama Books. pp. 215–217. ISBN 0-915361-10-8

- ^ Weinberg, p. 2

- ^ Schudson, Michael (1978). Discovering the News: A Social History of American Newspapers. New York: BasicBooks. p. 79

- ^ Chalmers, David Mark (1964). The Social and Political Ideas of Muckrakers. New York: Citadel Press. pp. 105–08

- ^ Wilson, p. 63

- ^ Weinberg, p. 441-443

- ^ Rivers, William L (1970). The Adversaries: Politics and the Press. Boston: Beacon Press. pp. 16–20

- ^ Steffens 1958, pp. 347–59.

- ^ Stephen E. Lucas, "Theodore Roosevelt's 'the man with the muck‐rake': A reinterpretation." Quarterly Journal of Speech 59#4 (1973): 452–462.

- ^ a b Roosevelt, Theodore (1958). Andrews, Wayne. ed. The Autobiography, Condensed from the Original Edition, Supplemented by Letters, Speeches, and Other Writings (1st ed.). New York City: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 246–47

- ^ SpartacusEducational.com. "Muckraking Journalism." (1997) Spartacus Educational. “Archived copy”. May 7, 2017時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2017年5月18日閲覧。. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- ^ Gallagher 2006, p. 13.

- ^ smithosonianmag.com "The Woman Who Took On a Tycoon." http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-woman-who-took-on-the-tycoon-651396/. Retrieved May 17, 2017.

- ^ a b Ushistory.org. "Muckrakers." (2014). U.S. History Online Textbook. http://www.ushistory.org/us/42b.asp. Retrieved January 21, 2014.

- ^ a b Weinberg, p. 195

- ^ Weinberg, p. 195

- ^ Lee D. Baker. "Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Her Passion for Justice." (1996) Duke University. “Archived copy”. May 8, 2017時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2017年5月18日閲覧。. Retrieved May 17, 2017.

- ^ Biography.com. "Ida B. Wells." (2017) Biography. “Archived copy”. February 23, 2017時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2017年2月17日閲覧。. Retrieved May 17, 2017.

- ^ Daly, Christopher (2012). Covering America : a narrative history of a nation's journalism. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 147–148. ISBN 978-1-55849-911-9. OCLC 793012714

- ^ Cook, Fred J. (1972). The Muckrakers: Crusading Journalists who Changed America. Garden City, New York: Doubleday. pp. 179

- ^ Daly, Christopher (2012). Covering America : a narrative history of a nation's journalism. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 147–148. ISBN 978-1-55849-911-9. OCLC 793012714

- ^ James L. Aucoin, The Evolution of American Investigative Journalism (University of Missouri Press, 2007) p. 90.

- ^ W. David Sloan; Lisa Mullikin Parcell (2002). American Journalism: History, Principles, Practices. McFarland. pp. 211–213. ISBN 9780786413713.

- ^ Cecelia Tichi, Exposés and excess: Muckraking in America, 1900/2000 (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013)

- ^ Stephen Hess, Whatever Happened to the Washington Reporters, 1978–2012 (2012)

Lincoln Steffens

[編集]| リンカーン | リンカン | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| シュテ | 清音 | 促音なし | ファンス | リンカーン・シュテファンス

× |

リンカン・シュテファンス

× |

| フェンス | リンカーン・シュテフェンス | リンカン・シュテフェンス

× | |||

| 促音あり | ッファンス | リンカーン・シュテッファンス

× |

リンカン・シュテッファンス

× | ||

| ッフェンス | リンカーン・シュテッフェンス

× |

リンカーン・シュテッフェンス

× | |||

| 濁音 | 促音なし | ファンズ | リンカーン・シュテファンズ

× |

リンカン・シュテファンズ

× | |

| フェンズ | リンカーン・シュテフェンズ

1 |

リンカン・シュテフェンズ

× | |||

| 促音あり | ッファンズ | リンカーン・シュテッファンズ

× |

リンカン・シュテッファンズ

× | ||

| ッフェンズ | リンカーン・シュテッフェンズ

× |

リンカーン・シュテッフェンズ

× | |||

| ステ | 清音 | 促音なし | ファンス | リンカーン・ステファンス

38 |

リンカン・ステファンス

1 |

| フェンス | リンカーン・ステフェンス

69+Google翻訳、ウィリアム・スティーブン・デブリー |

リンカン・ステフェンス

7+アメリカ文学 | |||

| 促音あり | ッファンス | リンカーン・ステッファンス

× |

リンカン・ステッファンス

× | ||

| ッフェンス | リンカーン・ステッフェンス

× |

リンカン・ステッフェンス

× | |||

| 濁音 | 促音なし | ファンズ | リンカーン・ステファンズ

200+ウォルター・リップマン *別人? |

リンカン・ステファンズ

42 | |

| フェンズ | リンカーン・ステフェンズ

130+コトバンク、イーダ・ターベル、国務省出版物 |

リンカン・ステフェンズ

49 | |||

| 促音あり | ッファンズ | リンカーン・ステッファンズ

× |

リンカン・ステッファンズ

× | ||

| ッフェンズ | リンカーン・ステッフェンズ

56+20世紀西洋人名辞典 |

リンカン・ステッフェンズ

× | |||

| なお、ステッフェンズのみでは100件+世界大百科事典 | |||||

- ^ n. (Joseph) Lincoln,ステフェンズ(1866-1936):米国のジャーナリスト・編集者;政界の汚職などを暴く muckrakers 運動の主導者.

- ^ ステフェンズ すてふぇんず Lincoln Steffens [1866―1936] アメリカのジャーナリスト。サンフランシスコ出身。ニューヨークで『マクルーアズ』誌などの編集に携わり、20世紀初頭から「マックレーキング(不正暴露)運動」の先頭にたち、当時の政界、実業界の癒着と腐敗を摘発する記事、論文を意欲的に発表。それらは主著『都市の恥辱 (ちじょく) 』(1904)、『自治のための戦い』(1906)に収録される。また『自伝』(1931)は彼の社会思想や当時の革新運動の動向を知るうえで興味深い。 [渡辺利雄]

- ^ ステフェンズ Steffens, Joseph Lincoln 1866.4.6~1936.8.9 アメリカのジャーナリスト. 《McClure's Magazine》誌 [1901-06] ,《The American Magazine》誌および《Everybody's Magazine》誌 [06-11] の編集に当たり,代表的なマクレイカーとしてセントルイスやミネアポリス,シカゴ,ニューヨーク等の大都市の市政腐敗の暴露その他に峻烈な筆を振るった.10年代以降は世界各地の革命運動に関心を寄せ,メキシコやロシアの政変を好意的に報じた. 〖主著〗The shame of the cities, 1904.The struggle for self-government, 1906.Autobiography of Lincoln Steffens, 2巻, 1931.