利用者:正親町三条/sandbox/sandbox 2

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

日本占領時期のフィリピンでは、第二次世界大戦中(1942年-1945年)の大日本帝国によるフィリピン統治について述べる。

真珠湾攻撃から10時間後にあたる1941年12月8日、大日本帝国によるフィリピン侵攻が開始された。真珠湾攻撃でアメリカ空軍が甚大な被害を受けたため、空からの援護を得られず、在フィリピン艦隊は1941年12月12日にジャバまで撤退した。これを受け、ダグラス・マッカーサーはコレヒドール島の友軍を見捨て、1942年3月11日の夜半、4,000km離れたオーストラリアに向け逃走した。取り残された76,000人のアメリカ兵とフィリピン兵は飢えや病気に苦しみ、1942年4月9日にバターン州にて日本軍に降伏した。捕虜となった彼らはバターン死の行進により、7,000-10,000人が死亡するか殺害された。1,3000人のコレヒドール島の生存者も5月6日に投降した。

大日本帝国は1945年の終戦まで3年にわたってフィリピンを支配した。中でも日本にとってゲリラ兵(うち60%は島やジャングル、山間部を根拠とした)は脅威であり、彼らはマッカーサーの潜水艦から救援物資を受け取り、同時に増員も行っていた。アメリカがここまでフィリピンを支援したのには理由があり、一つはアメリカが過去に独立を保証していたこと、もう一つは多くのフィリピン人が強制労働させられたり、若い女性は売春させられていたからであった[1]。

マッカーサーはフィリピンへ戻るという約束通りに1944年12月、フィリピンへ帰還した。レイテ沖海戦General MacArthur kept his promise to return to the Philippines on October 20, 1944. The landings on the island of Leyte were accompanied by a force of 700 vessels and 174,000 men. Through December 1944, the islands of Leyte and Mindoro were cleared of Japanese soldiers. During the campaign, the Imperial Japanese Army conducted a suicidal defense of the islands. Cities such as Manila were reduced to rubble. Between 500,000 and 1,000,000 Filipinos died during the occupation.

Background

[編集]Japan launched an attack on the Philippines on December 8, 1941, just ten hours after their attack on Pearl Harbor.[2] Initial aerial bombardment was followed by landings of ground troops both north and south of Manila.[3] The defending Philippine and United States troops were under the command of General Douglas MacArthur, who had been recalled to active duty in the United States Army earlier in the year and was designated commander of the United States Armed Forces in the Asia-Pacific region.[4] The aircraft of his command were destroyed; the naval forces were ordered to leave; and because of the circumstances in the Pacific region, reinforcement and resupply of his ground forces were impossible.[5] Under the pressure of superior numbers, the defending forces withdrew to the Bataan Peninsula and to the island of Corregidor at the entrance to Manila Bay.[6] Manila, declared an open city to prevent its destruction,[7] was occupied by the Japanese on January 2, 1942.[8]

The Philippine defense continued until the final surrender of U.S.-Philippine forces on the Bataan Peninsula in April 1942 and on Corregidor in May.[9] Most of the 80,000 prisoners of war captured by the Japanese at Bataan were forced to undertake the infamous "Bataan Death March" to a prison camp 105 kilometers to the north.[9] Thousands of men, weakened by disease and malnutrition and treated harshly by their captors, died before reaching their destination.[10] Quezon and Osmeña had accompanied the troops to Corregidor and later left for the United States, where they set up a government-in-exile.[11] MacArthur was ordered to Australia, where he started to plan for a return to the Philippines.[12]

The occupation

[編集]

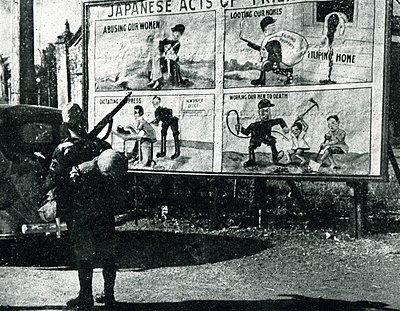

The Japanese military authorities immediately began organizing a new government structure in the Philippines. Although the Japanese had promised independence for the islands after occupation, they initially organized a Council of State through which they directed civil affairs until October 1943, when they declared the Philippines an independent republic.[13] Most of the Philippine elite, with a few notable exceptions, served under the Japanese.[14] The puppet republic was headed by President José P. Laurel.[15] Philippine collaboration in puppet government began under Jorge B. Vargas, who was originally appointed by Quezon as the mayor of Greater Manila before Quezon departed Manila.[16] The only political party allowed during the occupation was the Japanese-organized KALIBAPI.[17] During the occupation, most Filipinos remained loyal to the United States,[18] and war crimes committed by forces of the Empire of Japan against surrendered Allied forces,[19] and civilians were documented.[20]

Resistance

[編集]Japanese occupation of the Philippines was opposed by active and successful underground and guerrilla activity that increased over the years which eventually covered a large portion of the country. Opposing these guerrillas were a Japanese-formed Bureau of Constabulary (later taking the name of the old Constabulary during the Second Republic),[21][22] Kempeitai,[21] and the Makapili.[23] Postwar investigations showed that about 260,000 people were in guerrilla organizations and that members of the anti-Japanese underground were even more numerous. Such was their effectiveness that by the end of the war, Japan controlled only twelve of the forty-eight provinces.[24]

The Philippine guerrilla movement continued to grow, in spite of Japanese campaigns against them. Throughout Luzon and the southern islands, Filipinos joined various groups and vowed to fight the Japanese. The commanders of these groups made contact with one another, argued about who was in charge of what territory, and began to formulate plans to assist the return of American forces to the islands. They gathered important intelligence information and smuggled it out to the U.S. Army, a process that sometimes took months. General MacArthur formed a clandestine operation to support the guerrillas. He had Lieutenant Commander Charles "Chick" Parsons smuggle guns, radios and supplies to them by submarine. The guerrilla forces, in turn, built up their stashes of arms and explosives and made plans to assist MacArthur's invasion by sabotaging Japanese communications lines and attacking Japanese forces from the rear.[25]

Various guerrilla forces formed throughout the archipelago, ranging from groups of U.S. Army Forces Far East (USAFFE) forces who refused to surrender to local militia initially organized to combat banditry brought about by disorder caused by the invasion.[26] Several islands in the Visayas region had guerrilla forces led by Filipino officers, such as Colonel Macario Peralta in Panay,[26][27] Major Ismael Ingeniero in Bohol,[26][28] and Captain Salvador Abcede in Negros.[26][29] The island of Mindanao, being farthest from the center of Japanese occupation, had 38,000 guerrillas who were eventually consolidated under the command of American civil engineer Colonel Wendell Fertig.[26]

One resistance group in the Central Luzon area was known as the Hukbalahap (Hukbo ng Bayan Laban sa Hapon), or the People's Anti-Japanese Army, organized in early 1942 under the leadership of Luis Taruc, a communist party member since 1939. The Huks armed some 30,000 people and extended their control over portions of Luzon.[30] However, guerrilla activities on Luzon were hampered due to the heavy Japanese presence and infighting between the various groups,[31] including Hukbalahap troops attacking American-led guerrilla units.[32][33]

Lack of equipment, difficult terrain and undeveloped infrastructure made coordination of these groups nearly impossible, and for several months in 1942, all contact was lost with Philippine resistance forces. Communications were restored in November 1942 when the reformed Philippine 61st Division on Panay island, led by Colonel Macario Peralta, was able to establish radio contact with the USAFFE command in Australia. This enabled the forwarding of intelligence regarding Japanese forces in the Philippines to SWPA command, as well as consolidating the once sporadic guerrilla activities and allowing the guerrillas to help in the war effort.[26]

Increasing amounts of supplies and radios were delivered by submarine to aid the guerrilla effort. By the time of the Leyte invasion, four submarines were dedicated exclusively to the delivery of supplies.[26]

Other guerrilla units were attached to the SWPA, and were active throughout the archipelago. Some of these units were organized or directly connected to pre-surrender units ordered to mount guerrilla actions. An example of this was Troop C, 26th Cavalry.[34][35][36] Other guerrilla units were made up of former Philippine Army and Philippine Scouts soldiers who had been released from POW camps by the Japanese.[37][38] Others were combined units of Americans, military and civilian, who had never surrendered or had escaped after surrendering, and Filipinos, Christians and Moros, who had initially formed their own small units. Colonel Wendell Fertig organized such a group on Mindanao that not only effectively resisted the Japanese, but formed a complete government that often operated in the open throughout the island. Some guerrilla units would later be assisted by American submarines which delivered supplies,[39] evacuate refugees and injured,[40] as well as inserted individuals and whole units,[41] such as the 5217th Reconnaissance Battalion,[42] and Alamo Scouts.[42]

By the end of the war, some 277 separate guerrilla units, made up of some 260,715 individuals, fought in the resistance movement.[43] Select units of the resistance would go on to be reorganized and equipped as units of the Philippine Army and Constabulary.[44]

End of the occupation

[編集]When General MacArthur returned to the Philippines with his army in late 1944, he was well supplied with information; it is said that by the time MacArthur returned, he knew what every Japanese lieutenant ate for breakfast and where he had his hair cut. But the return was not easy. The Japanese Imperial General Staff decided to make the Philippines their final line of defense, and to stop the American advance toward Japan. They sent every available soldier, airplane, and naval vessel to the defense of the Philippines. The Kamikaze corps was created specifically to defend the Philippines. The Battle of Leyte Gulf ended in disaster for the Japanese and was the biggest naval battle of World War II. The campaign to re-take the Philippines was the bloodiest campaign of the Pacific War. Intelligence information gathered by the guerrillas averted a disaster—they revealed the plans of Japanese General Yamashita to trap MacArthur's army, and they led the liberating soldiers to the Japanese fortifications.[25]

MacArthur's Allied forces landed on the island of Leyte on October 20, 1944, accompanied by Osmeña, who had succeeded to the commonwealth presidency upon the death of Quezon on August 1, 1944. Landings then followed on the island of Mindoro and around Lingayen Gulf on the west side of Luzon, and the push toward Manila was initiated. The Commonwealth of the Philippines was restored. Fighting was fierce, particularly in the mountains of northern Luzon, where Japanese troops had retreated, and in Manila, where they put up a last-ditch resistance. The Philippine Commonwealth troops and the recognized guerrilla fighter units rose up everywhere for the final offensive.[45] Filipino guerrillas also played a large role during the liberation. One guerrilla unit came to substitute for a regularly constituted American division, and other guerrilla forces of battalion and regimental size supplemented the efforts of the U.S. Army units. Moreover, the loyal and willing Filipino population immeasurably eased the problems of supply, construction and civil administration and furthermore eased the task of Allied forces in recapturing the country.[46][47]

Fighting continued until Japan's formal surrender on September 2, 1945. The Philippines had suffered great loss of life and tremendous physical destruction by the time the war was over. An estimated one million Filipinos had been killed from all causes; of these 131,028 were listed as killed in seventy-two war crime events.[48] U.S. casualties were 10,380 dead and 36,550 wounded; Japanese dead were 255,795.[48]

See also

[編集]- Emergency circulating notes

- Japanese government-issued Philippine fiat peso

- Military history of the Philippines during World War II

- Santo Tomas Internment Camp

- Second Philippine Republic

References

[編集]- This article incorporates public domain text from the Library of Congress July 1994, Retrieved on 11 November 2008

- ^ The Philippines Campaign October 20, 1944 - August 15, 1945 - World War II Multimedia Database

- ^ MacArthur General Staff (1994). “The Japanese Offensive in the Philippines”. Report of General MacArthur: The Campaigns of MacArthur in the Pacific Volume I. GEN Harold Keith Johnson, BG Harold Nelson, Douglas MacArthur. United States Army. p. 6. LCCN 66--60005 24 March 2013閲覧。

- ^ Astor, Gerald (2009). Crisis in the Pacific: The Battles for the Philippine Islands by the Men Who Fought Them. Random House Digital, Inc.. pp. 52–240. ISBN 978-0-307-56565-5 24 March 2013閲覧。

“Japanese Landings in the Philippines”. ADBC (American Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor) Museum. Morgantown Public Library System. 24 March 2013閲覧。 - ^ “Douglas MacArthur”. History.com. A&E Television Networks, LLC.. 24 March 2013閲覧。

- ^ Morton, Louis. “The First Days of War”. In Greenfield, Kent Roberts. The Fall of the Philippines. United States Army in World War II. Orlando Ward. Washington, D.C.: United States Army. pp. 77–97. LCCN 53--63678 24 March 2013閲覧。

- ^ Morton, Louis (1960). “The Decision To Withdraw to Bataan”. In Greenfield, Kent Roberts. Command Decisions. Washington, D.C.: United States Army. pp. 151–172. LCCN 59--60007 24 March 2013閲覧。

- ^ “Manila an Open City”. Sunday Times. (28 December 1941) 25 March 2013閲覧。

- ^ “Manila Occupied by Japanese Forces”. Sunday Morning Herald. (3 January 1942) 24 March 2013閲覧。

“Timeline: World War II in the Philippines”. American Experience. WGBH (1999年). 24 March 2013閲覧。

Kintanar, Thelma B.; Aquino, Clemen C. (2006). Kuwentong Bayan: Noong Panahon Ng Hapon : Everyday Life in a Time of War. UP Press. p. 564. ISBN 978-971-542-498-1 24 March 2013閲覧。 - ^ a b “Philippines Map”. American Experience. WGBH (1999年). 24 March 2013閲覧。

Rottman, Gordon L. (2002). U.S. Marine Corps World War II Order of Battle: Ground and Air Units in the Pacific War, 1939–1945. Gale virtual reference library. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-313-31906-8 24 March 2013閲覧。 - ^ “The Bataan Death March”. Asian Pacific Americans in the United States Army. United States Army. 24 March 2013閲覧。

“Bataan Death March”. History.com. A&E Television Networks, LLC. 24 March 2013閲覧。

Dyess, William E. (1944). Bataan Death March: A Survivor's Account. University of Nebraska Press. p. xxi. ISBN 978-0-8032-6656-8 24 March 2013閲覧。

“New Mexico National Guard's involvement in the Bataan Death March”. Bataan Memorial Museum Foundation, Inc (2012年). 23 March 2013閲覧。 - ^ Hunt, Ray C.; Norling, Bernard (2000). Behind Japanese Lines: An American Guerilla in the Philippines. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 140–141. ISBN 978-0-8131-2755-2 23 March 2013閲覧。

Rogers, Paul P. (1990). The Good Years: MacArthur and Sutherland. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 160–169. ISBN 978-0-275-92918-3 24 March 2013閲覧。 - ^ Rogers, Paul P. (1990). The Good Years: MacArthur and Sutherland. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-275-92918-3 24 March 2013閲覧。

“President Roosevelt to MacArthur: Get out of the Philippines”. History.com. A&E Television Networks, LLC. 24 March 2013閲覧。

Bennett, William J. (2007). America: The Last Best Hope, Volume 1: From the Age of Discovery to a World at War, 1492–1914. Thomas Nelson Inc. p. 198. ISBN 978-1-59555-111-5 24 March 2013閲覧。 - ^ Guillermo, Artemio R. (2012). Historical Dictionary of the Philippines. Historical Dictionaries of Asia, Oceania, and the Middle East Series. Scarecrow Press. p. 211. ISBN 978-0-8108-7246-2 23 March 2013閲覧。

- ^ Schirmer, Daniel B.; Shalom, Stephen Rosskamm, eds (1897). “War Collaboration and Resistance”. The Philippines Reader: A History of Colonialism, Neocolonialism, Dictatorship, and Resistance. International Studies. South End Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-89608-275-5 23 March 2013閲覧。

Ooi, Keat Gin, ed (2004). Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. pp. 368–369. ISBN 978-1-57607-770-2 23 March 2013閲覧。

Riedinger, Jeffrey M. (1995). Agrarian Reform in the Philippines: Democratic Transitions and Redistributive Reform. Stanford University Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-8047-2530-9 23 March 2013閲覧。 - ^ Abinales, Patricio N.; Amoroso, Donna J. (2005). State And Society In The Philippines. State and Society in East Asia Series. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 159–160. ISBN 978-0-7425-1024-1 23 March 2013閲覧。

- ^ Pomeroy, William J. (1992). The Philippines: Colonialism, Collaboration, and Resistance. International Publishers Co. pp. 116–118. ISBN 978-0-7178-0692-8 23 March 2013閲覧。

- ^ Hunt, Ray C.; Norling, Bernard (2000). Behind Japanese Lines: An American Guerilla in the Philippines. University Press of Kentucky. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-8131-2755-2 23 March 2013閲覧。

- ^ Cyr, Arthur I.; Tucker, Spencer (2012). “Collaboration”. In Roberts, Priscilla. World War II: The Essential Reference Guide. ABC-CLIO. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-61069-101-7 23 March 2013閲覧。

- ^ “People & Events: Japanese Atrocities in the Philippines”. WGBH. PBS (2003年). 30 June 2011閲覧。

- ^ Frank Dexter (3 April 1945). “Appalling Stories of Jap Atrocities”. The Argus 30 June 2011閲覧。

AAP (24 March 1945). “Japs Murdered Spaniards in Manila”. The Argus 30 June 2011閲覧。

Gordon L. Rottman (2002). World War 2 Pacific Island Guide. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 318. ISBN 978-0-313-31395-0. "War crime trail affidavits list 131,028 Filipino civilians murdered in seventy-two large-scale massacres and remote incidents."

Werner Gruhl (31 December 2011). Imperial Japan's World War Two: 1931-1945. Transaction Publishers. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-4128-0926-9 - ^ a b “The Guerrilla War”. American Experience. PBS. 24 February 2011閲覧。

- ^ Jubair, Salah. “The Japanese Invasion”. Maranao.Com. 23 February 2011閲覧。

- ^ “Have a bolo will travel”. Asian Journal 24 February 2011閲覧。

- ^ Caraccilo, Dominic J. (2005). Surviving Bataan And Beyond: Colonel Irvin Alexander's Odyssey As A Japanese Prisoner Of War. Stackpole Books. pp. 287. ISBN 978-0-8117-3248-2

- ^ a b War in the Pacific

- ^ a b c d e f g “Guerrilla Activities in the Philippines”. Reports of General MacArthur. Template:Cite webの呼び出しエラー:引数 accessdate は必須です。

- ^ “General Macario Peralta, Jr.”. University of the Philippines - Reserve Officers' Training Corps. 4 February 2011閲覧。

- ^ Villanueva, Rudy; Renato E. Madrid (2003). The Vicente Rama reader: an introduction for modern readers. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press. p. 140. ISBN 971-550-441-8 4 January 2011閲覧。

- ^ Bradsher, Greg (2005). “The "Z Plan" Story: Japan's 1944 Naval Battle Strategy Drifts into U.S. Hands, Part 2”. Prologue Magazine (The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration) 37 (3) 4 February 2011閲覧。.

- ^ Dolan, Ronald E. “World War II, 1941–45”. Philippines : a country study (4th ed.). Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. ISBN 0-8444-0748-8

- ^ Schaefer, Chris (2004). Bataan Diary. Riverview Publishing. p. 434. ISBN 0-9761084-0-2

- ^ Houlahan, J. Michael (27 July 2005). “Book Review”. Philippine Scouts Heritage Society. 25 January 2011閲覧。

- ^ Valeriano, Napoleon D.; Charles T. R. Bohannan (2006). Counter-guerrilla operations: the Philippine experience. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-275-99265-1 7 May 2011閲覧。

- ^ Map of known insurgent activity

- ^ Norling, Bernard (2005). The Intrepid Guerrillas of North Luzon. University Press of Kentucky. p. 284. ISBN 9780813191348 21 May 2009閲覧。

- ^ “The Intrepid Guerrillas of North Luzon”. Defense Journal (2002年). 21 May 2009閲覧。

- ^ “Last of cavalrymen a true hero”. Old Gold & Black. Wake Forest University (6 March 2003). 21 May 2009閲覧。 [リンク切れ]

- ^ My Father by Jose Calugas Jr.

- ^ Hogan, David W., Jr. (1992). U.S. Army Special Operations in World War II. Washington, D.C.: Department of the Army. p. 81 25 January 2011閲覧。

- ^ Roscoe, Theodore; Richard G. Voge, United States Bureau of Naval Personnel (1949). United States submarine operations in World War II. Naval Institute Press. p. 577. ISBN 0-87021-731-3 25 January 2011閲覧。

- ^ Holian, Thomas (2004). “Saviors and Suppliers: World War II Submarine Special Operations in the Philippines”. Undersea Warfare (United States Navy) Summer (23) 25 January 2011閲覧。.

- ^ a b Rottman, Gordon L. (2005). US Special Warfare Units in the Pacific Theater 1941–45. Osprey Publishing. pp. 44–45. ISBN 978-1-84176-707-9 3 December 2009閲覧。

- ^ Schmidt, Larry S. (1982). American Involvement in the Filipino Resistance Movement on Mindanao During the Japanese Occupation, 1942–1945 (PDF) (Master of Military Art and Science thesis). U.S. Army Command and General Staff College. 2011年8月5日閲覧。

- ^ Rottman, Godron L. (2002). World War 2 Pacific island guide. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 318. ISBN 978-0-313-31395-0 7 May 2011閲覧。

- ^ Chambers, John Whiteclay; Fred Anderson (1999). The Oxford companion to American military history. New York, New York: Oxford University Press US. p. 547. ISBN 978-0-19-507198-6 7 May 2011閲覧。

- ^ http://www.history.army.mil/books/amh/AMH-23.htm World War II: The war against Japan by Robert W. Coakley. The Philippines Campaign

- ^ http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/bataan/peopleevents/p_filipinos.html Bataan Rescue. Filipinos and the war

- ^ a b Rottman, Gordon L. (2002). World War 2 Pacific island guide. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 318. ISBN 978-0-313-31395-0 9 January 2012閲覧。

Further reading

[編集]- Agoncillo Teodoro A. The Fateful Years: Japan's Adventure in the Philippines, 1941–1945. Quezon City, PI: R.P. Garcia Publishing Co., 1965. 2 vols

- Hartendorp A. V.H. The Japanese Occupation of the Philippines. Manila: Bookmark, 1967. 2 vols.

- Lear, Elmer. The Japanese Occupation of the Philippines: Leyte, 1941–1945. Southeast Asia Program, Department of Far Eastern Studies, Cornell University, 1961. 246p. emphasis on social history

- Steinberg, David J. Philippine Collaboration in World War II. University of Michigan Press, 1967. 235p.

Primary sources

[編集]- Ephraim, Frank (2003). Escape to Manila: From Nazi Tyranny to Japanese Terror. University of Illinois Press. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-252-02845-8

Template:JapanEmpireNavbox Template:Japanese occupations Template:Philippines topics