ハンチンチン

ハンチンチン(英: huntingtin、HTT)は、ヒトではHTT遺伝子によってコードされているタンパク質である。HTT遺伝子はIT15(interesting transcript 15)という別名でも知られる[5]。HTT遺伝子の変異はハンチントン病の原因となり、疾患における役割や長期記憶の保存との関係の研究が行われている[6]。

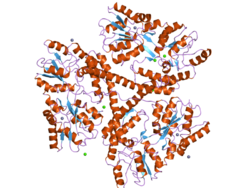

ハンチンチンの構造は多様であり、タンパク質中のグルタミン残基の数が異なる多くの多型が存在する。野生型(正常型)では多型部分には6個から35個のグルタミン残基が含まれているが、ハンチントン病患者では36個以上(最長報告例では約250個)のグルタミン残基が存在する[7]。

ハンチンチンタンパク質の分子量はグルタミン残基の数に大きく依存するが、予測分子量は約350kである。正常なハンチンチンは、一般的には3144アミノ酸からなる。このタンパク質の正確な機能は未解明であるが、神経細胞において重要な役割を果たしていることが知られている。細胞内では、ハンチンチンはシグナル伝達、物質の輸送、タンパク質やその他の構造への結合、アポトーシスからの保護に関与している可能性がある。ハンチンチンタンパク質は出生前の正常な発生に必要である[8]。

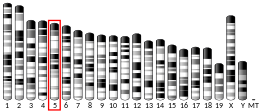

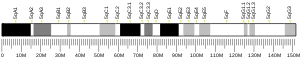

遺伝子

[編集]HTT遺伝子は4番染色体に位置する。HTT遺伝子には、グルタミンをコードするシトシン-アデニン-グアニン(CAG)からなる3塩基の繰り返し配列が存在する。この領域はトリヌクレオチドリピート(トリプレットリピート)と呼ばれる。このCAGリピートの数は10個から35個であることが多い[9]。

タンパク質

[編集]機能

[編集]ハンチンチンの機能はよく理解されていないが、軸索輸送に関与していることが知られている[10]。ハンチンチンは発生に必要不可欠であり、マウスではハンチンチンの欠失は致死となる[8]。ハンチンチンは他のタンパク質との配列相同性がみられず、ヒトや齧歯類では神経と精巣で高度に発現している[11]。ハンチンチンはBDNFの発現を転写レベルでアップレギュレーションするが、ハンチンチンがどのように遺伝子発現を調節しているのかは不明である[12]。免疫組織化学、電子顕微鏡、細胞分画研究により、ハンチンチンは主に小胞や微小管に結合して存在することが示されている[13][14]。このことは、ハンチンチンがミトコンドリアの細胞骨格への固定や輸送に機能していることを示唆している。ハンチンチンはクラスリン結合タンパク質であるHIP1と相互作用し、エンドサイトーシスを媒介する[15][16]。また、RAB11Aとの相互作用を介して上皮細胞極性の確立にも関与している[17]。

相互作用

[編集]ハンチンチンは少なくとも19種類のタンパク質と直接相互作用することが示されており、そのうち6種類は転写、4種類は輸送、3種類はシグナル伝達に関与し、その他の6種類(HIP5、HIP11、HIP13、HIP15、HIP16、CGI-125)は機能未知である[18]。また酵母ツーハイブリッドスクリーニングによって発見され、免疫沈降によって確認されたものとして、HAP1やHIPなど100種類以上の相互作用タンパク質が見つかっている[19][20]。

| 相互作用タンパク質 | ポリグルタミンの長さへの依存性 | 機能 |

|---|---|---|

| α-アダプチンC/HYPJ | あり | エンドサイトーシス |

| Akt/PKB | なし | キナーゼ |

| CBP | あり | アセチルトランスフェラーゼ活性を有する転写コアクチベーター |

| CA150 | なし | 転写コアクチベーター |

| CIP4 | あり | CDC42依存性シグナル伝達 |

| CtBP | あり | 転写因子 |

| FIP2 | 不明 | 細胞形態形成 |

| Grb2[21] | 不明 | 成長因子受容体結合タンパク質 |

| HAP1 | あり | メンブレントラフィック |

| HAP40 (F8A1, F8A2, F8A3) | 不明 | 未知 |

| HIP1 | あり | エンドサイトーシス、アポトーシス |

| HIP14/HYP-H | あり | 輸送、エンドサイトーシス |

| N-CoR | あり | 核内受容体のコリプレッサー |

| NF-κB | 不明 | 転写因子 |

| p53[22] | なし | 転写因子 |

| PACSIN1[23] | あり | エンドサイトーシス、アクチン細胞骨格 |

| DLG4 (PSD-95) | あり | シナプス後肥厚 |

| RASA1 (RasGAP)[21] | 不明 | Rasに対するGTPアーゼ活性化タンパク質 |

| SH3GL3[24] | あり | エンドサイトーシス |

| SIN3A | あり | 転写リプレッサー |

| Sp1[25] | あり | 転写因子 |

ハンチンチンは次に挙げる因子とも相互作用することが示されている。

ミトコンドリア機能不全

[編集]ハンチンチンはATM酸化DNA損傷応答複合体中の足場タンパク質である。ハンチンチンの変異はミトコンドリアの機能不全に重要な役割を果たしており、電子伝達系の阻害、高レベルの活性酸素種、酸化ストレスの増大を伴う[32][33]。DNAへの酸化損傷の促進はハンチントン病の病理に寄与している可能性がある[34]。

臨床的意義

[編集]| リピート数 | 分類 | 疾患状態 |

|---|---|---|

| <28 | 正常型(Normal) | 無症状 |

| 28–35 | 中間型(Intermediate) | 無症状 |

| 36–40 | 低浸透型(Reduced penetrance) | 一部が発症 |

| >40 | 完全浸透型(Full penetrance) | 発症 |

ハンチントン病はハンチンチン遺伝子の変異を原因とし、過剰な(36個以上の)CAGリピートの存在によって不安定なタンパク質が形成されることで引き起こされる[35]。こうしたリピートの拡大の結果、N末端に異常に長いポリグルタミン配列が含まれたハンチンチンタンパク質が産生されるようになる。そのためハンチントン病は、トリプレット病もしくはポリグルタミン病と呼ばれる神経変性疾患群の一部を構成している。ハンチントン病において重要な意味を持つは、18番目のアミノ酸から始まるグルタミン配列の拡大である。発症していない人物ではこの配列には9個から35個のグルタミン残基が含まれ、この長さでは悪影響が生じることはない[5]。36個から39個の場合、低い浸透率で疾患の発症がみられる[36]。

長いグルタミン配列を持つタンパク質は、細胞内の酵素によって断片へと切断されることが多い。こうしたタンパク質断片は神経細胞内部で神経核内封入体(neuronal intranuclear inclusions、NII)と呼ばれる異常な塊を形成し、また正常なタンパク質をこうした封入体へ引き込んでいる可能性もある。ハンチントン病患者でみられるこうした特徴的な封入体の存在が、疾患の発症に寄与していると考えられてきた[37]。しかしながらその後の研究では、観察可能なNIIの存在は神経細胞の寿命を伸ばし、近隣神経細胞内の変異型ハンチンチンを減少させることが示されており、こうした封入体が果たす役割には疑問が投げかけられている[38]。また、上述の研究では小さすぎて沈着物として認識されなかったようなものも含め、さまざまな種類の凝集体が変異型タンパク質によって形成されることが現在では認識されている[39]ことも混乱をもたらす1つの要因となっている。神経細胞死の可能性の予測は現在でも困難であるが、(1) ハンチンチン遺伝子中のCAGリピートの長さ、(2) 細胞内を拡散する変異型ハンチンチンタンパク質への曝露など、複数の因子が重要となると考えられている。NIIは単なる発症機構であるわけではなく、拡散するハンチンチンの量を減少させることで神経細胞死を食い止める対処機構として有用となる場合もある[40]。

36個から40個のCAGリピートを持つ場合にはハンチントン病の徴候や症状が生じる場合も生じない場合もある一方、40個より多くのリピートを持つ場合には正常な寿命のいずれかの時点で疾患を発症する。60個以上のリピートがある場合、若年性ハンチントン病と呼ばれる重症型の疾患を発症する。このように、グルタミンをコードするCAGリピートの数が疾患の発症年齢に影響を与える。36個よりも少ないリピートでハンチントン病と診断された例は報告されていない[36]。

出典

[編集]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000197386 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000029104 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ Human PubMed Reference:

- ^ Mouse PubMed Reference:

- ^ a b The Huntington's Disease Collaborative Research Group (Mar 1993). “A novel gene containing a trinucleotide repeat that is expanded and unstable on Huntington's disease chromosomes. The Huntington's Disease Collaborative Research Group”. Cell 72 (6): 971–83. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(93)90585-E. hdl:2027.42/30901. PMID 8458085.

- ^ “Huntingtin is critical both pre- and postsynaptically for long-term learning-related synaptic plasticity in Aplysia”. PLOS ONE 9 (7): e103004. (July 23, 2014). Bibcode: 2014PLoSO...9j3004C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0103004. PMC 4108396. PMID 25054562.

- ^ “Analysis of a very large trinucleotide repeat in a patient with juvenile Huntington's disease”. Neurology 52 (2): 392–4. (Jan 1999). doi:10.1212/wnl.52.2.392. PMID 9932964.

- ^ a b “Targeted disruption of the Huntington's disease gene results in embryonic lethality and behavioral and morphological changes in heterozygotes”. Cell 81 (5): 811–23. (Jun 1995). doi:10.1016/0092-8674(95)90542-1. PMID 7774020.

- ^ “HTT gene”. 2023年3月11日閲覧。

- ^ “Traffic signaling: new functions of huntingtin and axonal transport in neurological disease”. Current Opinion in Neurobiology 63: 122–130. (August 2020). doi:10.1016/j.conb.2020.04.001. PMID 32408142.

- ^ “Normal huntingtin function: an alternative approach to Huntington's disease”. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience 6 (12): 919–30. (December 2005). doi:10.1038/nrn1806. PMID 16288298.

- ^ “Loss of huntingtin-mediated BDNF gene transcription in Huntington's disease”. Science 293 (5529): 493–8. (July 2001). doi:10.1126/science.1059581. PMID 11408619.

- ^ “Perinuclear localization of huntingtin as a consequence of its binding to microtubules through an interaction with beta-tubulin: relevance to Huntington's disease”. Journal of Cell Science 115 (Pt 5): 941–8. (March 2002). doi:10.1242/jcs.115.5.941. PMID 11870213.

- ^ “Huntingtin is a cytoplasmic protein associated with vesicles in human and rat brain neurons”. Neuron 14 (5): 1075–81. (May 1995). doi:10.1016/0896-6273(95)90346-1. PMID 7748555.

- ^ “Wild-type and mutant huntingtins function in vesicle trafficking in the secretory and endocytic pathways”. Experimental Neurology 152 (1): 34–40. (July 1998). doi:10.1006/exnr.1998.6832. PMID 9682010.

- ^ “The huntingtin interacting protein HIP1 is a clathrin and alpha-adaptin-binding protein involved in receptor-mediated endocytosis”. Human Molecular Genetics 10 (17): 1807–17. (August 2001). doi:10.1093/hmg/10.17.1807. PMID 11532990.

- ^ “Huntingtin Is Required for Epithelial Polarity through RAB11A-Mediated Apical Trafficking of PAR3-aPKC”. PLOS Biology 13 (5): e1002142. (May 2015). doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1002142. PMC 4420272. PMID 25942483.

- ^ “The hunt for huntingtin function: interaction partners tell many different stories”. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 28 (8): 425–33. (Aug 2003). doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00168-3. PMID 12932731.

- ^ “A protein interaction network links GIT1, an enhancer of huntingtin aggregation, to Huntington's disease”. Molecular Cell 15 (6): 853–65. (Sep 2004). doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2004.09.016. PMID 15383276.

- ^ “HIP-I: a huntingtin interacting protein isolated by the yeast two-hybrid system”. Human Molecular Genetics 6 (3): 487–95. (Mar 1997). doi:10.1093/hmg/6.3.487. PMID 9147654.

- ^ a b “SH3 domain-dependent association of huntingtin with epidermal growth factor receptor signaling complexes”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 272 (13): 8121–4. (Mar 1997). doi:10.1074/jbc.272.13.8121. PMID 9079622.

- ^ “The Huntington's disease protein interacts with p53 and CREB-binding protein and represses transcription”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 97 (12): 6763–8. (Jun 2000). Bibcode: 2000PNAS...97.6763S. doi:10.1073/pnas.100110097. PMC 18731. PMID 10823891.

- ^ “PACSIN 1 interacts with huntingtin and is absent from synaptic varicosities in presymptomatic Huntington's disease brains”. Human Molecular Genetics 11 (21): 2547–58. (Oct 2002). doi:10.1093/hmg/11.21.2547. PMID 12354780.

- ^ “SH3GL3 associates with the Huntingtin exon 1 protein and promotes the formation of polygln-containing protein aggregates”. Molecular Cell 2 (4): 427–36. (Oct 1998). doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80142-2. PMID 9809064.

- ^ “Interaction of Huntington disease protein with transcriptional activator Sp1”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 22 (5): 1277–87. (Mar 2002). doi:10.1128/MCB.22.5.1277-1287.2002. PMC 134707. PMID 11839795.

- ^ “Huntingtin is ubiquitinated and interacts with a specific ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 271 (32): 19385–94. (Aug 1996). doi:10.1074/jbc.271.32.19385. PMID 8702625.

- ^ “Activation of MLK2-mediated signaling cascades by polyglutamine-expanded huntingtin”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 275 (25): 19035–40. (Jun 2000). doi:10.1074/jbc.C000180200. PMID 10801775.

- ^ “FIP-2, a coiled-coil protein, links Huntingtin to Rab8 and modulates cellular morphogenesis”. Current Biology 10 (24): 1603–6. (2000). doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00864-2. PMID 11137014.

- ^ a b c “Huntingtin interacts with a family of WW domain proteins”. Human Molecular Genetics 7 (9): 1463–74. (Sep 1998). doi:10.1093/hmg/7.9.1463. PMID 9700202.

- ^ “Cdc42-interacting protein 4 binds to huntingtin: neuropathologic and biological evidence for a role in Huntington's disease”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 100 (5): 2712–7. (Mar 2003). Bibcode: 2003PNAS..100.2712H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0437967100. PMC 151406. PMID 12604778.

- ^ “HIP14, a novel ankyrin domain-containing protein, links huntingtin to intracellular trafficking and endocytosis”. Human Molecular Genetics 11 (23): 2815–28. (Nov 2002). doi:10.1093/hmg/11.23.2815. PMID 12393793.

- ^ “Oxidative Stress in Neurodegenerative Diseases: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Applications”. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017: 2525967. (2017). doi:10.1155/2017/2525967. PMC 5529664. PMID 28785371.

- ^ Maiuri, Tamara; Mocle, Andrew J.; Hung, Claudia L.; Xia, Jianrun; van Roon-Mom, Willeke M. C.; Truant, Ray (25 December 2016). “Huntingtin is a scaffolding protein in the ATM oxidative DNA damage response complex”. Human Molecular Genetics 26 (2): 395–406. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddw395. PMID 28017939.

- ^ “Role of oxidative DNA damage in mitochondrial dysfunction and Huntington's disease pathogenesis”. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 62: 102–10. (September 2013). doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.04.017. PMC 3722255. PMID 23602907.

- ^ a b “Huntington's disease”. Lancet 369 (9557): 218–28. (Jan 2007). doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60111-1. PMID 17240289.

- ^ a b “Contribution of DNA sequence and CAG size to mutation frequencies of intermediate alleles for Huntington disease: evidence from single sperm analyses”. Human Molecular Genetics 6 (2): 301–9. (Feb 1997). doi:10.1093/hmg/6.2.301. PMID 9063751.

- ^ “Formation of neuronal intranuclear inclusions underlies the neurological dysfunction in mice transgenic for the HD mutation”. Cell 90 (3): 537–48. (Aug 1997). doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80513-9. PMID 9267033.

- ^ “Inclusion body formation reduces levels of mutant huntingtin and the risk of neuronal death”. Nature 431 (7010): 805–10. (Oct 2004). Bibcode: 2004Natur.431..805A. doi:10.1038/nature02998. PMID 15483602.

- ^ “Delayed Emergence of Subdiffraction-Sized Mutant Huntingtin Fibrils Following Inclusion Body Formation”. Q Rev Biophys 49: e2. (2016). doi:10.1017/S0033583515000219. PMC 4785097. PMID 26350150.

- ^ “Neurodegenerative disease: neuron protection agency”. Nature 431 (7010): 747–8. (Oct 2004). Bibcode: 2004Natur.431..747O. doi:10.1038/431747a. PMID 15483586.

関連文献

[編集]- “Myopathy as a first symptom of Huntington's disease in a Marathon runner”. Movement Disorders 22 (11): 1637–40. (August 2007). doi:10.1002/mds.21550. PMID 17534945.

- “Huntingtin aggregation and toxicity in Huntington's disease”. Lancet 361 (9369): 1642–4. (May 2003). doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13304-1. PMID 12747895.

- “Dysfunction of wild-type huntingtin in Huntington disease”. News in Physiological Sciences 18: 34–7. (Feb 2003). doi:10.1152/nips.01410.2002. PMID 12531930.

- “Huntington's disease: pathomechanism and therapeutic perspectives”. Journal of Neural Transmission 111 (10–11): 1485–94. (Oct 2004). doi:10.1007/s00702-004-0201-4. PMID 15480847.

- “Huntingtin and the molecular pathogenesis of Huntington's disease. Fourth in molecular medicine review series”. EMBO Reports 5 (10): 958–63. (Oct 2004). doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400250. PMC 1299150. PMID 15459747.

- “The localization and interactions of huntingtin”. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 354 (1386): 1021–7. (Jun 1999). doi:10.1098/rstb.1999.0454. PMC 1692601. PMID 10434301.

- “Huntingtin and its role in neuronal degeneration”. The Neuroscientist 10 (5): 467–75. (Oct 2004). doi:10.1177/1073858404266777. PMID 15359012.

- “The Huntington's disease candidate region exhibits many different haplotypes”. Nature Genetics 1 (2): 99–103. (May 1992). doi:10.1038/ng0592-99. PMID 1302016.

- “Huntingtin: alive and well and working in middle management”. Science's STKE 2003 (207): pe48. (Nov 2003). doi:10.1126/stke.2003.207.pe48. PMID 14600292.

- “Huntington's disease genetics”. NeuroRx 1 (2): 255–62. (Apr 2004). doi:10.1602/neurorx.1.2.255. PMC 534940. PMID 15717026.

- “Huntington's disease: how does huntingtin, an anti-apoptotic protein, become toxic?”. Pathologie-Biologie 52 (6): 338–42. (Jul 2004). doi:10.1016/j.patbio.2003.06.004. PMID 15261377.

- “Huntingtin in health and disease”. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 111 (3): 299–302. (Feb 2003). doi:10.1172/JCI17742. PMC 151871. PMID 12569151.

外部リンク

[編集]- Huntingtin protein, human - MeSH・アメリカ国立医学図書館・生命科学用語シソーラス

- The Huntingtin Protein and Protein Aggregation at HOPES : Huntington's Outreach Project for Education at Stanford

- The HDA Huntington's Disease Association UK

- Online 'Mendelian Inheritance in Man' (OMIM) 143100

- GeneCard

- iHOP