HSP90AA1

HSP90AA1(heat shock protein 90 alpha family class A member 1)もしくはHsp90α(Hsp90A)は、ヒトではHSP90AA1遺伝子にコードされるタンパク質である[5][6]。

機能

[編集]HSP90AA1遺伝子は、ストレス誘導性のHsp90αをコードする。パラログであるHsp90β(HSP90AB1)は恒常的に発現しており、アミノ酸同一性は86%である[7]。Hsp90ファミリーの一員として、Hsp90α二量体は分子シャペロン機能を果たし、他のタンパク質に結合して機能的な立体構造へのフォールディングを補助する。この分子シャペロン活性はATP加水分解のエネルギーによる構造的再編成のサイクルによって駆動される。Hsp90αは多数のがん促進タンパク質と相互作用しており、またストレスへの適応に関与しているため、薬剤標的としての役割に焦点を当てられている。

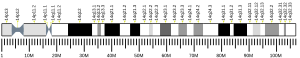

遺伝子構造

[編集]HSP90AA1遺伝子は14番染色体の14q32.33に位置し、長さは59 kb以上にわたる。3番、4番、11番、14番染色体にはHSP90AA1の偽遺伝子がいくつか存在している[8]。HSP90AA1遺伝子は異なる転写開始部位から転写される2種類のmRNA転写産物をコードしている。長いバリアント(TV1、NM_001017963.3)は854アミノ酸からなるアイソフォーム1(NP_001017963)をコードし、短いバリアント(TV2、NM_005348.3)は732アミノ酸からなるアイソフォーム2(NP_005339)をコードする。アイソフォーム1と2はN末端以外は同一である[9]。

発現

[編集]Hsp90αとHsp90βのアミノ酸配列には共通点がみられるが、発現調節の方法は異なっている。Hsp90αはストレスによって誘導されるのに対し、Hsp90βは恒常的に発現している。HSP90AA1の上流にはいくつかの熱ショックエレメント(heat shock element、HSE)が位置しており、誘導発現を可能にしている。

プロモーター

[編集]HSP90AA1遺伝子の転写は、ストレス時にマスター転写因子であるHSF1がHSP90AA1のプロモーターに結合することで誘導されることが明らかされている[10]。しかしながら、HSP90AA1プロモーターとともにヒトゲノムの広範囲の解析に焦点を当てたいくつかの研究では、他のさまざまな転写複合体もHSP90AA1の遺伝子発現を調節していることが示されている。哺乳類のHSP90AA1やHSP90AB1遺伝子の発現は形質転換したマウス細胞を用いて初めて特性解析がなされ、通常の条件下ではHSP90AB1がHSP90AA1よりも2.5倍高く恒常的に発現していることが示された。しかしながら、熱ショックに伴ってHSP90AA1の発現は7.0倍増加したのに対し、HSP90AB1は4.5倍しか増加しなかった[11]。HSP90AA1プロモーターの詳細な解析からは、転写開始部位から上流1200 bp以内に2つのHSEが存在することが示されている[12][13]。遠位のHSEは熱ショックによる誘導に必要であるのに対し、近位のHSEはpermissiveな状態にするエンハンサーとして機能する。このモデルは正常条件下の細胞のChIP-seq解析からも支持されており、HSF1は近位のHSEに結合しているのに対し、遠位のHSEでは検出されない。がん原タンパク質MYCもHSP90AA1遺伝子の発現を誘導することが知られており、転写開始部位近傍に結合することがChIP-seqによって確認されている。Hsp90Aの発現を欠乏させる実験からは、MYCによる形質転換にはHSP90AA1が必要であることが示されている[14]。乳がん細胞では、成長ホルモンであるプロラクチンがSTAT5を介してHSP90AA1の発現を誘導している[15]。NF-κB(RELA)もHSP90AA1の発現を誘導し、NF-κB転写の生存促進能力の説明となる可能性がある[16]。逆に、がん抑制因子であるSTAT1はHSP90AA1のストレス誘導性発現を阻害する[17]。これらの知見に加え、ヒトゲノムのChIP-seq解析からはHSP90AA1プロモーター領域内のRNAポリメラーゼII (POLR2A) 結合部位には合計85種類の転写因子が結合することが示されている[18][19][20][21]。このことはHSP90AA1遺伝子の発現は高度に調節された複雑なものである可能性を示している。

インタラクトーム

[編集]Hsp90αとHsp90βを合わせると、真核生物のプロテオームの10%と相互作用することが予測されている[22]。ヒトでは、およそ2000種類の相互作用タンパク質とのネットワークを形成していることとなる。現在、Hsp90αとHsp90βの双方に関して725種類以上の相互作用が実験的に示されている[23][24]。こうした多くのタンパク質と関係することで、Hsp90は多様なタンパク質相互作用ネットワークを連結するハブとして機能している。こうしたネットワークにおいて、Hsp90は主にシグナル伝達や情報のプロセシングに関与するタンパク質を維持し調節する専門的役割を果たしている。Hsp90の相互作用パートナーには、遺伝子発現を開始する転写因子、他のタンパク質を翻訳後修飾することで情報を伝達するキナーゼ、標的タンパク質のプロテアソームを介した分解をもたらすE3リガーゼなどが含まれる。LUMIER法を用いた近年の研究では、ヒトのHsp90βは全ての転写因子の7%、全てのキナーゼの60%、全てのE3リガーゼの30%と相互作用することが示されている[25]。他の研究では、Hsp90はさまざまな構造タンパク質、リボソームタンパク質、代謝酵素とも相互作用することが示されている[26][27]。また、HIVやエボラウイルスを含む、多数のウイルスタンパク質と相互作用することも知られている[28][29]。Hsp90の活性を調節し、指揮する多数のコシャペロンが存在することは言うまでもない[30]。一方で、Hsp90αとHsp90βとで異なるタンパク質相互作用を見分けることに焦点を当てた研究は少ない[31][32]。ツメガエルの卵や酵母で行われた研究では、Hsp90αとHsp90βではコシャペロンやクライアントタンパク質との相互作用が異なることが示されている[33][34]。しかしながら、ヒトの各パラログに割り当てられた固有の機能に関する理解はほとんど得られていない。Hsp90の相互作用データはHsp90Int.DBウェブサイトに集約されている[24]。Hsp90αとHsp90βの双方のインタラクトームのオントロジー解析からは、各パラログはそれぞれ固有の生物学的過程、分子的機能、細胞内構成要素と関係していることが示されている。

HSP90AA1は次に挙げる因子と相互作用することが示されている。

- AHSA1[35]

- AKT1[36][37][38]

- AR[39][40]

- C-Raf[41][42]

- CDC37[43][44]

- DAP3[45]

- EPRS[46]

- ERN1[47]

- ESR1[48][49]

- FKBP5[50]

- GNA12[51]

- GUCY1B3[52]

- HER2/neu[53][54]

- HSF1[48][55]

- Hop[56][57]

- NOS3[52][58][59]

- NR3C1[45][60][61][62][63][64][65]

- P53[66][67][68]

- PIM1[69]

- PPARA[70]

- SMYD3[71]

- STK11[72]

- TGFBR1[73]

- TGFBR2[73]

- TERT[36][37]

翻訳後修飾

[編集]翻訳後修飾は、Hsp90の調節に大きな影響を及ぼす。Hsp90が持つ多くの機能を調節するため、リン酸化、アセチル化、S-ニトロシル化、酸化、ユビキチン化による修飾がなされる。修飾部位はPhosphoSitePlusで知ることができる[74]。こうした部位の多くはHsp90αとHsp90βで保存されているが、いくつかの違いによってHsp90α特異的な機能が発揮される。

Hsp90のリン酸化はクライアントタンパク質、コシャペロン、ヌクレオチドの結合に影響を与えることが示されている[75][76][77][78][79][80]。Hsp90α特異的なリン酸化も行われることが示されている。こうしたユニークなリン酸化部位は、Hsp90αの分泌などの機能のシグナルとなったり、DNA損傷領域への移動や、特異的コシャペロンとの相互作用を引き起こす[75][78][81][82]。また、Hsp90αの高アセチル化も分泌を引き起こし、がんの浸潤性の増加をもたらす[83]。

臨床的意義

[編集]Hsp90αの発現は疾患の予後と関係していることが知られている。Hsp90αの発現レベルの上昇は、白血病、乳がん、膵臓がんの他、慢性閉塞性肺疾患(COPD)の患者でも見られる[84][85][86][87][88]。ヒトのT細胞では、HSP90AA1の発現は、IL-2、IL-4、IL-13といったサイトカインによって上昇する[89]。プロテオスタシスを維持するための相互作用を行うHsp90やその他の保存されたシャペロン・コシャペロンは、老化したヒトの脳では抑制されている。アルツハイマー病やハンチントン病などの加齢関連神経変性疾患の患者の脳では、この抑制がさらに悪化していることが明らかにされている[90]。

がん

[編集]ここ20年で、Hsp90はがんとの闘いにおける興味深い標的であることが明らかとなってきた。Hsp90は発がんを促進する多数のタンパク質と相互作用して補助していることから、悪性形質転換やプログレッションに必要不可欠であると考えられており、"cancer enabler"であると見なされている。さらに、どちらのパラログも広範囲のインタラクトームを介してがんの各特徴と関係している[91][92]。しかしながら、がんゲノムアトラス(TCGA)のデータによると、大部分の腫瘍でHSP90AA1遺伝子に変化は生じていない。Hsp90の全体的な発現レベルは細胞内の他のタンパク質と比較して高く維持されており[93]、Hsp90の発現レベルがさらに高くなることはがんの成長に利益をもたらさない可能性があるため、HSP90AA1遺伝子に変異が少ないことは驚くにはあらたないかもしれない。一方、最も多くの変化が生じているのは膀胱がんであり、膵臓がんが続く[94][95]。全ての腫瘍種やがん細胞株の全ゲノムシーケンシングからは、HSP90AA1遺伝子のオープンリーディングフレームに現在115種類の異なる変異が確認されている。しかしながら、これらの変異がHsp90αの機能に与える影響は明らかではない。特筆すべきこととしては、HSP90AA1遺伝子がホモ接合型で欠失したいくつかの腫瘍では、悪性度が低下している可能性が示唆されている。このことは206人の胃がん患者の比較ゲノムワイド解析からも支持されており、HSP90AA1の喪失は手術のみによる治療後の予後良好と関係している[96]。そして、腫瘍生検試料中のHsp90αの非存在が良好な臨床転帰のバイオマーカーとなる可能性が支持されている[97][98]。

Hsp90αのHsp90βとの生物学的な差異は、Hsp90αは細胞内での役割に加えて、創傷治癒や炎症時に細胞外へ分泌されて機能することが現在理解されている点である。これら2つの過程はがんに乗っ取られることが多く、悪性細胞の運動性、転移、血管外漏出を可能にしている[99]。前立腺がんに関する現在の研究からは、細胞外のHsp90αはがん関連線維芽細胞の慢性炎症を促進するシグナルを伝達することが示されている。こうした悪性腺腫細胞周囲の細胞外環境のリプログラミングは、前立腺がんのプログレッションを刺激することが理解されている。細胞外のHsp90αは、NF-κB(RELA)とSTAT3による転写プログラムの活性化によって炎症を誘導する。この転写プログラムには炎症性サイトカインIL-6やIL-8が含まれている[100]。また、それと同時にNF-κBはHsp90αの発現も誘導する[16]。その結果、刺激された線維芽細胞からは新たに合成されたHsp90αが分泌され、悪性部位で炎症ストームを生み出す自己分泌・傍分泌ポジティブフィードバックループが形成される、というモデルが提唱されている。この考えは、進行した悪性腫瘍患者の血漿中のHsp90α濃度の増加の相関の説明となる可能性があり、さらなる注目に値する[81]。

Hsp90阻害剤

[編集]がん細胞は多くのキナーゼや転写因子など、活性化されたがんタンパク質を補助するためにHsp90を利用している。悪性腫瘍ではこうしたクライアントタンパク質の遺伝子には変異、増幅、転座が生じていることが多く、悪性形質転換によって誘導された細胞ストレスの緩衝材としてHsp90は機能している[91][92]。Hsp90の阻害によって、クライアントタンパク質の多くに分解もしくは不安定性がもたらされる[101]。そのため、Hsp90はがん治療における魅力的な標的となっている。全てのATPアーゼと同様、in vivoでのHsp90のシャペロン機能にはATPの結合と加水分解が必要不可欠である。ATPと置き換わるHsp90阻害剤はこのサイクルの初期段階に干渉し、大部分のクライアントタンパク質のユビキチン化とプロテアソームを介した分解を引き起こす[102][103]。したがって、阻害剤の開発にはヌクレオチド結合ポケットが最も適している[104][105][106][107][108][109][110][111][112][113][114][115][116][117][118]。2014年時点で、Hsp90阻害剤に関しては腫瘍分野で23種類の試験が行われており、13種類のHsp90阻害剤でがん患者での臨床評価が進行している[119]。Hsp90のN末端のヌクレオチド結合ポケットが最も広く研究されて標的となっているが、近年の研究ではC末端領域にも2つ目のATP結合部位が存在することが示唆されている[120][121][122][123][124]。この領域の標的化によって、特定のホルモンとHsp90との相互作用が低下し、またHsp90のヌクレオチド結合に影響が生じることが示されている[125][126]。このC末端領域を標的とした阻害剤で臨床使用されたものはまだないが、N末端領域とC末端領域を標的とした阻害剤の併用は化学療法の新たな戦略となる可能性がある。上述した阻害剤の多くはHsp90の同じ部位(N末端もしくはC末端)を標的とするが、こうした薬剤の一部にはHsp90の翻訳後修飾の程度によって異なる選択性で結合するものがあることが示されている[127][128]。現在発表されている阻害剤の中でHsp90αとHsp90βを区別できるものはまだないが、近年の研究ではHsp90のN末端の特定の残基のリン酸化がアイソフォーム特異的な阻害剤結合をもたらすことが示されており[128]、Hsp90の標的化を新たなレベルで最適に調節することが可能となっている。

出典

[編集]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000080824 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000021270 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ Human PubMed Reference:

- ^ Mouse PubMed Reference:

- ^ “Sequence and regulation of a gene encoding a human 89-kilodalton heat shock protein”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 9 (6): 2615–26. (Jun 1989). doi:10.1128/MCB.9.6.2615. PMC 362334. PMID 2527334.

- ^ “The HSP90 family of genes in the human genome: insights into their divergence and evolution”. Genomics 86 (6): 627–37. (Dec 2005). doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.08.012. PMID 16269234.

- ^ Zuehlke, Abbey D.; Beebe, Kristin; Neckers, Len; Prince, Thomas (2015-10-01). “Regulation and function of the human HSP90AA1 gene”. Gene 570 (1): 8–16. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2015.06.018. ISSN 1879-0038. PMC 4519370. PMID 26071189.

- ^ “Mapping of the gene family for human heat-shock protein 90 alpha to chromosomes 1, 4, 11, and 14”. Genomics 12 (2): 214–20. (Feb 1992). doi:10.1016/0888-7543(92)90368-3. PMID 1740332.

- ^ “HSP90AA1 heat shock protein 90 alpha family class A member 1 [Homo sapiens (human) - Gene - NCBI]”. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. 2023年2月5日閲覧。

- ^ .“Heat shock proteins and heat shock factor 1 in carcinogenesis and tumor development: an update”. Archives of Toxicology 87 (1): 19–48. (Jan 2013). doi:10.1007/s00204-012-0918-z. PMC 3905791. PMID 22885793.

- ^ “Transcriptional and translational analysis of the murine 84- and 86-kDa heat shock proteins”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 264 (12): 6810–6. (Apr 1989). doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)83502-5. PMID 2708345.

- ^ “Regulation of human hsp90alpha gene expression”. FEBS Letters 444 (1): 130–5. (Feb 1999). doi:10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00044-7. PMID 10037161.

- ^ “Hsp90 isoforms: functions, expression and clinical importance”. FEBS Letters 562 (1–3): 11–5. (Mar 2004). doi:10.1016/s0014-5793(04)00229-7. PMID 15069952.

- ^ “Direct activation of HSP90A transcription by c-Myc contributes to c-Myc-induced transformation”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 279 (15): 14649–55. (Apr 2004). doi:10.1074/jbc.M308842200. PMID 14724288.

- ^ “Heat shock protein-90-alpha, a prolactin-STAT5 target gene identified in breast cancer cells, is involved in apoptosis regulation”. Breast Cancer Research 10 (6): R94. (2008). doi:10.1186/bcr2193. PMC 2656886. PMID 19014541.

- ^ a b “The activity of hsp90 alpha promoter is regulated by NF-kappa B transcription factors”. Oncogene 27 (8): 1175–8. (Feb 2008). doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1210716. PMID 17724475.

- ^ “Diverse effects of Stat1 on the regulation of hsp90alpha gene under heat shock”. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry 102 (4): 1059–66. (Nov 2007). doi:10.1002/jcb.21342. PMID 17427945.

- ^ “Factorbook.org: a Wiki-based database for transcription factor-binding data generated by the ENCODE consortium”. Nucleic Acids Research 41 (Database issue): D171–6. (Jan 2013). doi:10.1093/nar/gks1221. PMC 3531197. PMID 23203885.

- ^ “ENCODE data in the UCSC Genome Browser: year 5 update”. Nucleic Acids Research 41 (Database issue): D56–63. (Jan 2013). doi:10.1093/nar/gks1172. PMC 3531152. PMID 23193274.

- ^ “Mapping of transcription factor binding regions in mammalian cells by ChIP: comparison of array- and sequencing-based technologies”. Genome Research 17 (6): 898–909. (Jun 2007). doi:10.1101/gr.5583007. PMC 1891348. PMID 17568005.

- ^ “High-throughput methods of regulatory element discovery”. BioTechniques 41 (6): 673–681. (Dec 2006). doi:10.2144/000112322. PMID 17191608.

- ^ “Navigating the chaperone network: an integrative map of physical and genetic interactions mediated by the hsp90 chaperone”. Cell 120 (5): 715–27. (Mar 2005). doi:10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.024. PMID 15766533.

- ^ “An interaction network predicted from public data as a discovery tool: application to the Hsp90 molecular chaperone machine”. PLOS ONE 6 (10): e26044. (2011). Bibcode: 2011PLoSO...626044E. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0026044. PMC 3195953. PMID 22022502.

- ^ a b Dupuis. “Hsp90 PPI database”. 2023年2月12日閲覧。

- ^ “A quantitative chaperone interaction network reveals the architecture of cellular protein homeostasis pathways”. Cell 158 (2): 434–48. (Jul 2014). doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.039. PMC 4104544. PMID 25036637.

- ^ “A proteomic snapshot of the human heat shock protein 90 interactome”. FEBS Letters 579 (28): 6350–4. (Nov 2005). doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2005.10.020. PMID 16263121.

- ^ “Label-free quantitative proteomics and SAINT analysis enable interactome mapping for the human Ser/Thr protein phosphatase 5”. Proteomics 11 (8): 1508–16. (Apr 2011). doi:10.1002/pmic.201000770. PMC 3086140. PMID 21360678.

- ^ “Hsp90: a chaperone for HIV-1”. Parasitology 141 (9): 1192–202. (Aug 2014). doi:10.1017/S0031182014000298. PMID 25004926.

- ^ “Inhibition of heat-shock protein 90 reduces Ebola virus replication”. Antiviral Research 87 (2): 187–94. (Aug 2010). doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2010.04.015. PMC 2907434. PMID 20452380.

- ^ “The Hsp90 chaperone machinery: conformational dynamics and regulation by co-chaperones”. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 1823 (3): 624–35. (Mar 2012). doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.09.003. PMID 21951723.

- ^ “A proteomic investigation of ligand-dependent HSP90 complexes reveals CHORDC1 as a novel ADP-dependent HSP90-interacting protein”. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 9 (2): 255–70. (Feb 2010). doi:10.1074/mcp.M900261-MCP200. PMC 2830838. PMID 19875381.

- ^ “Approaches for defining the Hsp90-dependent proteome”. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 1823 (3): 656–67. (Mar 2012). doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.08.013. PMC 3276727. PMID 21906632.

- ^ “A comparison of Hsp90alpha and Hsp90beta interactions with cochaperones and substrates”. Biochemistry and Cell Biology 86 (1): 37–45. (Feb 2008). doi:10.1139/o07-154. PMID 18364744.

- ^ “An atlas of chaperone-protein interactions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: implications to protein folding pathways in the cell”. Molecular Systems Biology 5: 275. (2009). doi:10.1038/msb.2009.26. PMC 2710862. PMID 19536198.

- ^ “Activation of the ATPase activity of hsp90 by the stress-regulated cochaperone aha1”. Molecular Cell 10 (6): 1307–18. (Dec 2002). doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00785-2. PMID 12504007.

- ^ a b “Regulation of telomerase activity and anti-apoptotic function by protein-protein interaction and phosphorylation”. FEBS Letters 536 (1–3): 180–6. (Feb 2003). doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(03)00058-9. PMID 12586360.

- ^ a b “IL-2 increases human telomerase reverse transcriptase activity transcriptionally and posttranslationally through phosphatidylinositol 3'-kinase/Akt, heat shock protein 90, and mammalian target of rapamycin in transformed NK cells”. Journal of Immunology 174 (9): 5261–9. (May 2005). doi:10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5261. PMID 15843522.

- ^ “Modulation of Akt kinase activity by binding to Hsp90”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 97 (20): 10832–7. (Sep 2000). Bibcode: 2000PNAS...9710832S. doi:10.1073/pnas.170276797. PMC 27109. PMID 10995457.

- ^ “Anti-androgens and the mutated androgen receptor of LNCaP cells: differential effects on binding affinity, heat-shock protein interaction, and transcription activation”. Biochemistry 31 (8): 2393–9. (Mar 1992). doi:10.1021/bi00123a026. PMID 1540595.

- ^ “Association of the 90-kDa heat shock protein does not affect the ligand-binding ability of androgen receptor”. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 42 (8): 803–12. (Sep 1992). doi:10.1016/0960-0760(92)90088-Z. PMID 1525041.

- ^ “Raf exists in a native heterocomplex with hsp90 and p50 that can be reconstituted in a cell-free system”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 268 (29): 21711–6. (Oct 1993). doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(20)80600-0. PMID 8408024.

- ^ “X-linked and cellular IAPs modulate the stability of C-RAF kinase and cell motility”. Nature Cell Biology 10 (12): 1447–55. (Dec 2008). doi:10.1038/ncb1804. PMID 19011619.

- ^ “The Mechanism of Hsp90 regulation by the protein kinase-specific cochaperone p50(cdc37)”. Cell 116 (1): 87–98. (Jan 2004). doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)01027-4. PMID 14718169.

- ^ “p50(cdc37) binds directly to the catalytic domain of Raf as well as to a site on hsp90 that is topologically adjacent to the tetratricopeptide repeat binding site”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 273 (32): 20090–5. (Aug 1998). doi:10.1074/jbc.273.32.20090. PMID 9685350.

- ^ a b “The pro-apoptotic protein death-associated protein 3 (DAP3) interacts with the glucocorticoid receptor and affects the receptor function”. The Biochemical Journal 349 (3): 885–93. (Aug 2000). doi:10.1042/bj3490885. PMC 1221218. PMID 10903152.

- ^ “Heat shock protein 90 mediates protein-protein interactions between human aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 275 (41): 31682–8. (Oct 2000). doi:10.1074/jbc.M909965199. PMID 10913161.

- ^ “Heat shock protein 90 modulates the unfolded protein response by stabilizing IRE1alpha”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 22 (24): 8506–13. (Dec 2002). doi:10.1128/MCB.22.24.8506-8513.2002. PMC 139892. PMID 12446770.

- ^ a b “A pathway of multi-chaperone interactions common to diverse regulatory proteins: estrogen receptor, Fes tyrosine kinase, heat shock transcription factor Hsf1, and the aryl hydrocarbon receptor”. Cell Stress & Chaperones 1 (4): 237–50. (Dec 1996). PMC 376461. PMID 9222609.

- ^ “Radicicol represses the transcriptional function of the estrogen receptor by suppressing the stabilization of the receptor by heat shock protein 90”. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 188 (1–2): 47–54. (Feb 2002). doi:10.1016/S0303-7207(01)00753-5. PMID 11911945.

- ^ “Molecular cloning of human FKBP51 and comparisons of immunophilin interactions with Hsp90 and progesterone receptor”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 17 (2): 594–603. (Feb 1997). doi:10.1128/MCB.17.2.594. PMC 231784. PMID 9001212.

- ^ “Interaction between the G alpha subunit of heterotrimeric G(12) protein and Hsp90 is required for G alpha(12) signaling”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 276 (49): 46088–93. (Dec 2001). doi:10.1074/jbc.M108711200. PMID 11598136.

- ^ a b “Novel complexes of guanylate cyclase with heat shock protein 90 and nitric oxide synthase”. American Journal of Physiology. Heart and Circulatory Physiology 285 (2): H669–78. (Aug 2003). doi:10.1152/ajpheart.01025.2002. PMID 12676772.

- ^ “Sensitivity of mature Erbb2 to geldanamycin is conferred by its kinase domain and is mediated by the chaperone protein Hsp90”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 276 (5): 3702–8. (Feb 2001). doi:10.1074/jbc.M006864200. PMID 11071886.

- ^ “Quercetin-induced ubiquitination and down-regulation of Her-2/neu”. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry 105 (2): 585–95. (Oct 2008). doi:10.1002/jcb.21859. PMC 2575035. PMID 18655187.

- ^ “HSF-1 interacts with Ral-binding protein 1 in a stress-responsive, multiprotein complex with HSP90 in vivo”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 278 (19): 17299–306. (May 2003). doi:10.1074/jbc.M300788200. PMID 12621024.

- ^ “Structure of TPR domain-peptide complexes: critical elements in the assembly of the Hsp70-Hsp90 multichaperone machine”. Cell 101 (2): 199–210. (Apr 2000). doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80830-2. PMID 10786835.

- ^ “Hop modulates Hsp70/Hsp90 interactions in protein folding”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 273 (6): 3679–86. (Feb 1998). doi:10.1074/jbc.273.6.3679. PMID 9452498.

- ^ “Role of heat shock protein 90 in bradykinin-stimulated endothelial nitric oxide release”. General Pharmacology 35 (3): 165–70. (Sep 2000). doi:10.1016/S0306-3623(01)00104-5. PMID 11744239.

- ^ “Native LDL and minimally oxidized LDL differentially regulate superoxide anion in vascular endothelium in situ”. American Journal of Physiology. Heart and Circulatory Physiology 283 (2): H750–9. (Aug 2002). doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00029.2002. PMID 12124224.

- ^ “Delimitation of two regions in the 90-kDa heat shock protein (Hsp90) able to interact with the glucocorticosteroid receptor (GR)”. Experimental Cell Research 247 (2): 461–74. (Mar 1999). doi:10.1006/excr.1998.4375. PMID 10066374.

- ^ “Nucleotide binding states of hsp70 and hsp90 during sequential steps in the process of glucocorticoid receptor.hsp90 heterocomplex assembly”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 277 (37): 33698–703. (Sep 2002). doi:10.1074/jbc.M204164200. PMID 12093808.

- ^ “Evidence that the beta-isoform of the human glucocorticoid receptor does not act as a physiologically significant repressor”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 272 (42): 26659–64. (Oct 1997). doi:10.1074/jbc.272.42.26659. PMID 9334248.

- ^ “The non-ligand binding beta-isoform of the human glucocorticoid receptor (hGR beta): tissue levels, mechanism of action, and potential physiologic role”. Molecular Medicine (Cambridge, Mass.) 2 (5): 597–607. (Sep 1996). doi:10.1007/BF03401643. PMC 2230188. PMID 8898375.

- ^ “Agonist-free transformation of the glucocorticoid receptor in human B-lymphoma cells”. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 57 (3–4): 239–49. (Feb 1996). doi:10.1016/0960-0760(95)00271-5. PMID 8645634.

- ^ “Use of the thiol-specific derivatizing agent N-iodoacetyl-3-[125I]iodotyrosine to demonstrate conformational differences between the unbound and hsp90-bound glucocorticoid receptor hormone binding domain”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 271 (15): 8831–6. (Apr 1996). doi:10.1074/jbc.271.15.8831. PMID 8621522.

- ^ “Phosphorylation and hsp90 binding mediate heat shock stabilization of p53”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 278 (3): 2066–71. (Jan 2003). doi:10.1074/jbc.M206697200. PMID 12427754.

- ^ “A role for Hsc70 in regulating nucleocytoplasmic transport of a temperature-sensitive p53 (p53Val-135)”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 276 (18): 14649–57. (May 2001). doi:10.1074/jbc.M100200200. PMID 11297531.

- ^ “Inhibition of MDM2 by hsp90 contributes to mutant p53 stabilization”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 276 (44): 40583–90. (Nov 2001). doi:10.1074/jbc.M102817200. PMID 11507088.

- ^ “Regulation of Pim-1 by Hsp90”. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 281 (3): 663–9. (Mar 2001). doi:10.1006/bbrc.2001.4405. PMID 11237709.

- ^ “Evidence that peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha is complexed with the 90-kDa heat shock protein and the hepatitis virus B X-associated protein 2”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 278 (7): 4467–73. (Feb 2003). doi:10.1074/jbc.M211261200. PMID 12482853.

- ^ “SMYD3 encodes a histone methyltransferase involved in the proliferation of cancer cells”. Nature Cell Biology 6 (8): 731–40. (Aug 2004). doi:10.1038/ncb1151. PMID 15235609.

- ^ “Heat-shock protein 90 and Cdc37 interact with LKB1 and regulate its stability”. The Biochemical Journal 370 (Pt 3): 849–57. (Mar 2003). doi:10.1042/BJ20021813. PMC 1223241. PMID 12489981.

- ^ a b “Critical regulation of TGFbeta signaling by Hsp90”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105 (27): 9244–9. (Jul 2008). Bibcode: 2008PNAS..105.9244W. doi:10.1073/pnas.0800163105. PMC 2453700. PMID 18591668.

- ^ “PhosphoSitePlus, 2014: mutations, PTMs and recalibrations”. Nucleic Acids Research 43 (Database issue): D512–20. (Jan 2015). doi:10.1093/nar/gku1267. PMC 4383998. PMID 25514926.

- ^ a b “C-terminal phosphorylation of Hsp70 and Hsp90 regulates alternate binding to co-chaperones CHIP and HOP to determine cellular protein folding/degradation balances”. Oncogene 32 (25): 3101–10. (Jun 2013). doi:10.1038/onc.2012.314. PMID 22824801.

- ^ “Threonine 22 phosphorylation attenuates Hsp90 interaction with cochaperones and affects its chaperone activity”. Molecular Cell 41 (6): 672–81. (Mar 2011). doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2011.02.011. PMC 3062913. PMID 21419342.

- ^ “Hsp90 phosphorylation, Wee1 and the cell cycle”. Cell Cycle 9 (12): 2310–6. (Jun 2010). doi:10.4161/cc.9.12.12054. PMC 7316391. PMID 20519952.

- ^ a b “Heat shock protein 90α (Hsp90α) is phosphorylated in response to DNA damage and accumulates in repair foci”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 287 (12): 8803–15. (Mar 2012). doi:10.1074/jbc.M111.320887. PMC 3308794. PMID 22270370.

- ^ “Hsp90 phosphorylation is linked to its chaperoning function. Assembly of the reovirus cell attachment protein”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 276 (35): 32822–7. (Aug 2001). doi:10.1074/jbc.M105562200. PMID 11438552.

- ^ “Dynamic tyrosine phosphorylation modulates cycling of the HSP90-P50(CDC37)-AHA1 chaperone machine”. Molecular Cell 47 (3): 434–43. (Aug 2012). doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.015. PMC 3418412. PMID 22727666.

- ^ a b “The regulatory mechanism of Hsp90alpha secretion and its function in tumor malignancy”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106 (50): 21288–93. (Dec 2009). Bibcode: 2009PNAS..10621288W. doi:10.1073/pnas.0908151106. PMC 2795546. PMID 19965370.

- ^ “Protein kinase A-dependent translocation of Hsp90 alpha impairs endothelial nitric-oxide synthase activity in high glucose and diabetes”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 282 (13): 9364–71. (Mar 2007). doi:10.1074/jbc.M608985200. PMID 17202141.

- ^ “Role of acetylation and extracellular location of heat shock protein 90alpha in tumor cell invasion”. Cancer Research 68 (12): 4833–42. (Jun 2008). doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0644. PMC 2665713. PMID 18559531.

- ^ “High constitutive expression of heat shock protein 90 alpha in human acute leukemia cells”. Leukemia Research 16 (6–7): 597–605. (1992). doi:10.1016/0145-2126(92)90008-u. PMID 1635378.

- ^ “High expression of heat shock protein 90 alpha and its significance in human acute leukemia cells”. Gene 542 (2): 122–8. (Jun 2014). doi:10.1016/j.gene.2014.03.046. PMID 24680776.

- ^ “Clinical and biological significance of HSP89 alpha in human breast cancer”. International Journal of Cancer 50 (3): 409–15. (Feb 1992). doi:10.1002/ijc.2910500315. PMID 1735610.

- ^ “Differential expression of heat shock proteins in pancreatic carcinoma”. Cancer Research 54 (2): 547–51. (Jan 1994). PMID 8275493.

- ^ “Elevated HSP27, HSP70 and HSP90 alpha in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: markers for immune activation and tissue destruction”. Clinical Laboratory 55 (1–2): 31–40. (2009). PMID 19350847.

- ^ “Interleukin-4 upregulates the heat shock protein Hsp90alpha and enhances transcription of a reporter gene coupled to a single heat shock element”. FEBS Letters 385 (1–2): 25–8. (Apr 1996). doi:10.1016/0014-5793(96)00341-9. PMID 8641459.

- ^ “A conserved chaperome sub-network safeguards protein homeostasis in aging and neurodegenerative disease”. Cell Rep. 9 (3): 1135–1150. (2014). doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.042. PMC 4255334. PMID 25437566.

- ^ a b “Drugging the cancer chaperone HSP90: combinatorial therapeutic exploitation of oncogene addiction and tumor stress”. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1113 (1): 202–16. (Oct 2007). Bibcode: 2007NYASA1113..202W. doi:10.1196/annals.1391.012. PMID 17513464.

- ^ a b “Targeting the dynamic HSP90 complex in cancer”. Nature Reviews. Cancer 10 (8): 537–49. (Aug 2010). doi:10.1038/nrc2887. PMC 6778733. PMID 20651736.

- ^ “Proteomic data from human cell cultures refine mechanisms of chaperone-mediated protein homeostasis”. Cell Stress & Chaperones 18 (5): 591–605. (Sep 2013). doi:10.1007/s12192-013-0413-3. PMC 3745260. PMID 23430704.

- ^ “Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal”. Science Signaling 6 (269): pl1. (Apr 2013). doi:10.1126/scisignal.2004088. PMC 4160307. PMID 23550210.

- ^ “The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data”. Cancer Discovery 2 (5): 401–4. (May 2012). doi:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095. PMC 3956037. PMID 22588877.

- ^ “Losses of chromosome 5q and 14q are associated with favorable clinical outcome of patients with gastric cancer”. The Oncologist 17 (5): 653–62. (2012). doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0379. PMC 3360905. PMID 22531355.

- ^ “Integration of gene dosage and gene expression in non-small cell lung cancer, identification of HSP90 as potential target”. PLOS ONE 3 (3): e0001722. (5 March 2008). Bibcode: 2008PLoSO...3.1722G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001722. PMC 2254495. PMID 18320023.

- ^ “Amplification and high-level expression of heat shock protein 90 marks aggressive phenotypes of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 negative breast cancer”. Breast Cancer Research 14 (2): R62. (17 April 2012). doi:10.1186/bcr3168. PMC 3446397. PMID 22510516.

- ^ “Functional proteomic screens reveal an essential extracellular role for hsp90 alpha in cancer cell invasiveness”. Nature Cell Biology 6 (6): 507–14. (Jun 2004). doi:10.1038/ncb1131. PMID 15146192.

- ^ “Extracellular Hsp90 mediates an NF-κB dependent inflammatory stromal program: implications for the prostate tumor microenvironment”. The Prostate 74 (4): 395–407. (Apr 2014). doi:10.1002/pros.22761. PMC 4306584. PMID 24338924.

- ^ “Hsp90 inhibitors: small molecules that transform the Hsp90 protein folding machinery into a catalyst for protein degradation”. Medicinal Research Reviews 26 (3): 310–38. (May 2006). doi:10.1002/med.20052. PMID 16385472.

- ^ “Interaction of Hsp90 with 20S proteasome: thermodynamic and kinetic characterization”. Proteins 48 (2): 169–77. (Aug 2002). doi:10.1002/prot.10101. PMID 12112686.

- ^ “Quality control and fate determination of Hsp90 client proteins”. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 1823 (3): 683–8. (Mar 2012). doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.08.006. PMC 3242914. PMID 21871502.

- ^ “Inhibition of heat shock protein HSP90-pp60v-src heteroprotein complex formation by benzoquinone ansamycins: essential role for stress proteins in oncogenic transformation”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 91 (18): 8324–8. (Aug 1994). Bibcode: 1994PNAS...91.8324W. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.18.8324. PMC 44598. PMID 8078881.

- ^ “Identification and structural characterization of the ATP/ADP-binding site in the Hsp90 molecular chaperone”. Cell 90 (1): 65–75. (Jul 1997). doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80314-1. PMID 9230303.

- ^ “Crystal structure of an Hsp90-geldanamycin complex: targeting of a protein chaperone by an antitumor agent”. Cell 89 (2): 239–50. (Apr 1997). doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80203-2. PMID 9108479.

- ^ “The amino-terminal domain of heat shock protein 90 (hsp90) that binds geldanamycin is an ATP/ADP switch domain that regulates hsp90 conformation”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 272 (38): 23843–50. (Sep 1997). doi:10.1074/jbc.272.38.23843. PMID 9295332.

- ^ “Targeting of the protein chaperone, HSP90, by the transformation suppressing agent, radicicol”. Oncogene 16 (20): 2639–45. (May 1998). doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1201790. PMID 9632140.

- ^ “Antibiotic radicicol binds to the N-terminal domain of Hsp90 and shares important biologic activities with geldanamycin”. Cell Stress & Chaperones 3 (2): 100–8. (Jun 1998). PMC 312953. PMID 9672245.

- ^ “Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationships for the heat shock protein 90 molecular chaperone inhibitor 17-allylamino, 17-demethoxygeldanamycin in human ovarian cancer xenograft models”. Clinical Cancer Research 11 (19 Pt 1): 7023–32. (Oct 2005). doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0518. PMID 16203796.

- ^ “Purine-scaffold Hsp90 inhibitors”. IDrugs: The Investigational Drugs Journal 9 (11): 778–82. (Nov 2006). PMID 17096299.

- ^ “NVP-AUY922: a novel heat shock protein 90 inhibitor active against xenograft tumor growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis”. Cancer Research 68 (8): 2850–60. (Apr 2008). doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5256. PMID 18413753.

- ^ “Phase I trial of 17-dimethylaminoethylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin (17-DMAG), a heat shock protein inhibitor, administered twice weekly in patients with advanced malignancies”. European Journal of Cancer 46 (2): 340–7. (Jan 2010). doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2009.10.026. PMC 2818572. PMID 19945858.

- ^ “Phase I study of the heat shock protein 90 inhibitor alvespimycin (KOS-1022, 17-DMAG) administered intravenously twice weekly to patients with acute myeloid leukemia”. Leukemia 24 (4): 699–705. (Apr 2010). doi:10.1038/leu.2009.292. PMID 20111068.

- ^ “A phase I study of the heat shock protein 90 inhibitor alvespimycin (17-DMAG) given intravenously to patients with advanced solid tumors”. Clinical Cancer Research 17 (6): 1561–70. (Mar 2011). doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1927. PMC 3060938. PMID 21278242.

- ^ “HSP90 inhibitors for cancer therapy and overcoming drug resistance”. Current Challenges in Personalized Cancer Medicine. Advances in Pharmacology. 65. (2012). pp. 471–517. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-397927-8.00015-4. ISBN 9780123979278. PMID 22959035

- ^ “Targeting heat shock proteins in cancer”. Cancer Letters 332 (2): 275–85. (May 2013). doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2010.10.014. PMID 21078542.

- ^ “Selective targeting of the stress chaperome as a therapeutic strategy”. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 35 (11): 592–603. (Nov 2014). doi:10.1016/j.tips.2014.09.001. PMC 4254259. PMID 25262919.

- ^ “Stressing the development of small molecules targeting HSP90”. Clinical Cancer Research 20 (2): 275–7. (Jan 2014). doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2571. PMID 24166908.

- ^ “The 90-kDa molecular chaperone family: structure, function, and clinical applications. A comprehensive review”. Pharmacology & Therapeutics 79 (2): 129–68. (Aug 1998). doi:10.1016/s0163-7258(98)00013-8. PMID 9749880.

- ^ “The heat shock protein 90 antagonist novobiocin interacts with a previously unrecognized ATP-binding domain in the carboxyl terminus of the chaperone”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 275 (47): 37181–6. (Nov 2000). doi:10.1074/jbc.M003701200. PMID 10945979.

- ^ “Binding of ATP to heat shock protein 90: evidence for an ATP-binding site in the C-terminal domain”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 277 (14): 12208–14. (Apr 2002). doi:10.1074/jbc.M111874200. PMID 11805114.

- ^ “Comparative analysis of the ATP-binding sites of Hsp90 by nucleotide affinity cleavage: a distinct nucleotide specificity of the C-terminal ATP-binding site”. European Journal of Biochemistry 270 (11): 2421–8. (Jun 2003). doi:10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03610.x. PMID 12755697.

- ^ “Elucidation of the Hsp90 C-terminal inhibitor binding site”. ACS Chemical Biology 6 (8): 800–7. (Aug 2011). doi:10.1021/cb200052x. PMC 3164513. PMID 21548602.

- ^ “Inhibition of Hsp90: a new strategy for inhibiting protein kinases”. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Proteins and Proteomics 1697 (1–2): 233–42. (Mar 2004). doi:10.1016/j.bbapap.2003.11.027. PMID 15023364.

- ^ “The heat shock protein 90-targeting drug cisplatin selectively inhibits steroid receptor activation”. Molecular Endocrinology 17 (10): 1991–2001. (Oct 2003). doi:10.1210/me.2003-0141. PMID 12869591.

- ^ “Affinity-based proteomics reveal cancer-specific networks coordinated by Hsp90”. Nature Chemical Biology 7 (11): 818–26. (Nov 2011). doi:10.1038/nchembio.670. PMC 3265389. PMID 21946277.

- ^ a b “Posttranslational modification and conformational state of heat shock protein 90 differentially affect binding of chemically diverse small molecule inhibitors”. Oncotarget 4 (7): 1065–74. (Jul 2013). doi:10.18632/oncotarget.1099. PMC 3759666. PMID 23867252.

関連文献

[編集]- “The 90-kDa molecular chaperone family: structure, function, and clinical applications. A comprehensive review”. Pharmacology & Therapeutics 79 (2): 129–68. (Aug 1998). doi:10.1016/S0163-7258(98)00013-8. PMID 9749880.

- “Hsp90: a specialized but essential protein-folding tool”. The Journal of Cell Biology 154 (2): 267–73. (Jul 2001). doi:10.1083/jcb.200104079. PMC 2150759. PMID 11470816.

- “Functional and prognostic role of ZAP-70 in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia”. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets 9 (6): 1165–78. (Dec 2005). doi:10.1517/14728222.9.6.1165. PMID 16300468.

- “Mechanisms of disease: the role of heat-shock protein 90 in genitourinary malignancy”. Nature Clinical Practice Urology 3 (11): 590–601. (Nov 2006). doi:10.1038/ncpuro0604. PMID 17088927.