「ワタリバッタ」の版間の差分

一部を修正。 |

en:Locust oldid=1222725796 を翻訳して加筆 タグ: サイズの大幅な増減 曖昧さ回避ページへのリンク |

||

| 1行目: | 1行目: | ||

[[File:Locusta-migratoria-wanderheuschrecke.jpg|thumb|[[トノサマバッタ]]({{snamei|Locusta migratoria}})のような一部のバッタの群生相が蝗害を引き起こす。]] |

|||

[[ファイル:CSIRO ScienceImage 7007 Plague locusts on the move.jpg|thumb|260px|大量発生したワタリバッタ]] |

|||

[[ファイル:CSIRO ScienceImage 7007 Plague locusts on the move.jpg|thumb|大量発生した[[オーストラリアトビバッタ]]]] |

|||

'''ワタリバッタ'''([[w:locust|locust]])とは、[[バッタ科]]の[[バッタ]]のうち、[[サバクトビバッタ]]や[[トノサマバッタ]]のように、大量発生などにより[[相変異 (動物)|相変異]]を起こして群生相となることがあるものをいう。しばしば[[蝗害]]をもたらすことで知られる。'''トビバッタ'''ともいう。訳語として「いなご(蝗)」が与えられることもあるが、生物学的な意味での[[イナゴ]]とは異なる。 |

|||

'''ワタリバッタ'''({{lang-en|[[w:locust|locust]]}}{{efn|[[ラテン語]]でワタリバッタまたはロブスターを意味する ''locusta'' が語源<ref>{{OEtymD|locust}}</ref>}})とは、[[バッタ科]]の[[バッタ]]のうち、[[サバクトビバッタ]]や[[トノサマバッタ]]のように、大量発生などにより[[相変異 (動物)|相変異]]を起こして群生相となることがあるものをいう。'''トビバッタ'''ともいう。訳語として「いなご(蝗)」が与えられることもあるが、生物学的な意味での[[イナゴ]]とは異なる。バッタとワタリバッタの分類学上の違いはなく、群生相を生じるかどうかで区別される。進化上複数回独立して群生相の獲得が生じており、少なくとも5亜科18属が知られている。 |

|||

[[飛翔]]距離は1日100[[キロメートル]]に達することがある。農作物を食い荒らす[[害虫]]で、[[国際連合食糧農業機関]](FAO)によると、[[アフガニスタン]]や[[ウズベキスタン]]、[[ロシア連邦]]など10カ国で毎年平均870万[[ヘクタール]]の被害が出る。2003年には[[西アフリカ]]20カ国以上の1300万ヘクタールで大発生した<ref>「2020 国際植物防疫年」『[[日本農業新聞]]』2020年1月4日6面の用語解説。</ref>。 |

通常、これらバッタは無害で、個体数は少なく、農業上の莫大な経済的脅威とはならない。しかしながら、急速な植生の成長後に[[旱魃]]が生じると、脳内の[[セロトニン]]によって急激な変化が生じる。急速に増殖し、個体数が十分に大きくなると群生・移動的になる({{仮リンク|昆虫の渡り|en|Insect migration|label=渡り}}と形容される)。翅のない[[若虫]]は集団(band)を形成し、翅を持った成虫の群れ(swarm)となる。集団と群れはどちらも動き回り、植生を食べつくし作物を{{仮リンク|有害生物|en|Pest (organism)|label=食害}}する。成虫は強力な飛行者であり、[[飛翔]]距離は1日100[[キロメートル]]に達することがある。農作物を食い荒らす[[害虫]]で、[[国際連合食糧農業機関]](FAO)によると、[[アフガニスタン]]や[[ウズベキスタン]]、[[ロシア連邦]]など10カ国で毎年平均870万[[ヘクタール]]の被害が出る。2003年には[[西アフリカ]]20カ国以上の1300万ヘクタールで大発生した<ref>「2020 国際植物防疫年」『[[日本農業新聞]]』2020年1月4日6面の用語解説。</ref>。 |

||

[[先史時代]]よりしばしば[[蝗害]]をもたらしてきたことで知られる。[[古代エジプト]]では墓に彫られており、また『[[イーリアス]]』『[[マハーバーラタ]]』『[[聖書]]』『[[コーラン]]』にも記述されている。蝗害は作物を壊滅させ、[[飢饉]]や人々の移住を引き起こしてきた。近年では、[[農業|農法]]の変化ワタリバッタ産卵地調査の向上により、初期段階での防除が可能となっている。伝統的な防除では地上または空中からの[[殺虫剤]]散布に頼っていたが、近年の[[生物的防除]]がより効果的である。群行動は20世紀に減少していったが、近年の調査・防除法にもかかわらず、今日でも依然存在する。気候条件が整い、警戒を怠れば蝗害が引き起こされる。 |

|||

ワタリバッタは大型の昆虫であり、動物学の研究や学校教育に有用である。また[[昆虫食|食用]]にもなり、歴史を通して食べられてきたほか、多くの国で[[高級食材]]とされている。 |

|||

== バッタの群れ == |

|||

{{main|バッタ|{{仮リンク|群行動|en|Swarm behaviour}}|{{仮リンク|捕食者飽食|en|Predator satiation}}}} |

|||

{{external media |width = 210px |float = right |headerimage= |video1 = [https://knowablemagazine.org/article/living-world/2020/locusts-and-grasshoppers-things-know "Locusts and Grasshoppers - Things to Know"], ''[[Knowable Magazine]]'', 2020.}} |

|||

ワタリバッタは[[バッタ科]]に属する角の短いバッタのうち、{{仮リンク|群行動|en|Swarm behaviour}}を取るものを指す。これらの虫は基本単独性だが、特定の環境下では個体数が増加し、行動・環境が変化して[[社会 (生物)|群生相]]となる<ref name="CurrentBio">{{cite journal|author1=Simpson, Stephen J. |author2= Sword, Gregory A. |title=Locusts|journal=Current Biology|volume=18|issue=9|pages=R364–R366|doi=10.1016/j.cub.2008.02.029|pmid=18460311|year=2008|doi-access=free|bibcode= 2008CBio...18.R364S }}{{Open access}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.fao.org/ag/locusts/en/info/info/faq/ |title=Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about locusts |work=Locust watch |publisher=FAO |access-date=1 April 2015}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.animalcorner.co.uk/insects/grasshoppers/grasshopper_about.html |title=Grasshoppers |work=Animal Corner |access-date=1 April 2015 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150408004426/http://www.animalcorner.co.uk/insects/grasshoppers/grasshopper_about.html |archive-date=8 April 2015 }}</ref>。 |

|||

[[File:Copulating desert locust pair.jpg|thumb|left|交尾中のサバクトビバッタ]] |

|||

ワタリバッタとバッタは[[分類学]]上では区別されない。基本的に、その種が断続的に適切な条件下で群れを形成するかどうかで定義される。英語の "locust" は群生相が[[形態学 (生物学)|形態]]・行動ともに変化し、未熟個体の集団から群れが発達する種を指す。変化は密度依存型[[表現型可塑性]]と説明される<ref name="Pener Simpson 2009">{{cite book |last1=Pener |first1=Meir Paul |last2=Simpson |first2=Stephen J. |volume=36 |isbn=9780123814289 |series=Advances in Insect Physiology |title=Locust Phase Polyphenism: An Update |date=14 October 2009 |publication-date=23 September 2009 |edition=1st |page=9 |publisher=Academic Press}}></ref>。 |

|||

これらの変化は[[相変異 (動物)|相変異]]の一例であり、{{仮リンク|対蝗研究所|en|Anti-Locust Research Centre}}の設立に貢献した{{仮リンク|ボリス・ウヴァロフ|en|Boris Uvarov}}によって初めて研究・記述された<ref>{{cite journal |last=Baron |first=Stanley |title=The Desert Locust |journal=[[New Scientist]] |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=yhMXtivOrZ4C&pg=PA156 |date=1972 |page=156}}</ref>。当時、別種とされていた[[コーカサス]]の孤独相および群生相のワタリバッタ({{snamei|Locusta migratoria}} と {{snamei|L. danica}} L.)について研究する中で、彼は相変異を発見した。彼は二相をそれぞれ ''solitaria'' および ''gregaria'' と命名した<ref name=Dingle1996>{{cite book |last=Dingle |first=Hugh |title=Migration: The Biology of Life on the Move |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qzzJoVfgg0QC&pg=PA273 |year=1996 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-535827-8 |pages=273–274}}</ref>。これらは定住型(statary)および渡り型(migratory)と呼ばれているが、厳密にいえば渡りよりは放浪に近い行動をとる。[[チャールズ・バレンタイン・ライリー]]や{{仮リンク|ノーマン・クリドル|en|Norman Criddle}}がワタリバッタの研究と防除に貢献した<ref>[[Wikisource:The Encyclopedia Americana (1920)/Riley, Charles Valentine]]</ref><ref>{{cite web |last=Holliday |first=N. J. |url=http://www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/mb_history/51/criddle_n.shtml |title=Norman Criddle: Pioneer Entomologist of the Prairies |date=1 February 2006 |work=Manitoba History |publisher=Manitoba Historical Society |access-date=2015-4-16}}</ref>。 |

|||

群行動は過密に対する応答である。後脚への触覚刺激増加によってセロトニンが増加する<ref>{{cite news |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/7858996.stm |work=BBC News |last=Morgan |first=James |title=Locust swarms 'high' on serotonin |date=29 January 2009 |access-date= 2014-3-4 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131010043157/http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/7858996.stm |archive-date=10 October 2013}}</ref>。これを受けて体色が変化し、摂食量や繁殖頻度が増加する。群生相への変化は4時間以上にわたる毎分数回以上の接触によって引き起こされる<ref>{{cite journal |year=2003 |title=Mechanosensory-induced behavioral gregarization in the desert locust ''Schistocerca gregaria'' |journal=[[Journal of Experimental Biology]] |volume=206 |issue=22 |pages=3991–4002 |doi=10.1242/jeb.00648 |pmid=14555739 |last1=Rogers |first1=S. M. |last2=Matheson |first2=T. |last3=Despland |first3=E. |last4=Dodgson |first4=T. |last5=Burrows |first5=M. |last6=Simpson |first6=S. J. |s2cid=10665260 |doi-access= }}{{Open access}}</ref>。巨大な群れは何十億もの個体が数千平方キロメートルの領域に広がっており、1平方キロメートルあたりの個体密度は8000万ほどにもなる(1平方マイルあたり20億個体)<ref name=Showler/>。サバクトビバッタが出会った際、神経系からセロトニンが放出され、群行動への前段階として相互に引き付けられる<ref>{{cite journal |last=Stevenson |first=P. A. |date=2009 |title=The key to Pandora's box |journal=[[Science (journal)|Science]] |volume=323 |issue=5914 |pages=594–595 |pmid=19179520 |doi=10.1126/science.1169280|s2cid=39306643 }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn16505-blocking-happiness-chemical-may-prevent-locust-plagues.html |title=Blocking 'happiness' chemical may prevent locust plagues |publisher=New Scientist |date=29 January 2009 |access-date=31 January 2009 |author=Callaway, Ewen }}</ref><ref name="Antsey Rogers Swidbert 2009">{{cite journal |last1=Antsey |first1=Michael |last2=Rogers |first2=Stephen |last3=Swidbert |first3=R.O. |last4=Burrows |first4=Malcolm |last5=Simpson |first5=S.J. |title=Serotonin mediates behavioral gregarization underlying swarm formation in desert locusts |journal=Science |date=30 January 2009 |volume=323|issue=5914 |pages=627–630 |doi=10.1126/science.1165939 |pmid=19179529 |bibcode=2009Sci...323..627A |s2cid=5448884 }}</ref>。 |

|||

群生相の最初の集団形成は発生(outbreak)と呼ばれ、より大きな集団への合流は急増(upsurge)として知られる。別の繁殖地で急増した集団が、地域レベルで継続的に集まることで[[蝗害]](plagues)となる<ref name=Showler2013>{{cite web |last=Showler |first=Allan T. |url=http://ipmworld.umn.edu/chapters/showler.htm |title=The Desert Locust in Africa and Western Asia: Complexities of War, Politics, Perilous Terrain, and Development |date=4 March 2013 |work=Radcliffe's IPM World Textbook |publisher=University of Minnesota |access-date=3 April 2015 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150408034918/http://ipmworld.umn.edu/chapters/showler.htm |archive-date=8 April 2015 }}</ref>。発生および急増初期では、集団中の一部の個体のみが群生相となり、集団をより広い範囲へと拡散していく。時間が経過するにつれ、バッタはより群生的になり、集団はより狭い範囲へと密集していく。1966年から1969年まで続いたアフリカ・中東・アジアでのサバクトビバッタの蝗害では、2世代によって個体数は200から300奥にまで増加したが、群れの面積は100,000平方キロメートルから5,000平方キロにまで減少した<ref name=Krall453/>。 |

|||

=== 孤独相と群生相 === |

|||

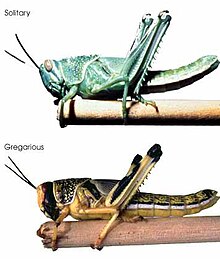

[[File:DesertLocust.jpeg|thumb|サバクトビバッタの孤独相と群生相]] |

|||

孤独相と群生相の大きな違いとして、行動が挙げられる。群生相の若虫は早ければ2{{仮リンク|齢期|en|Instar|label=齢}}から互いに惹きつけ合い、すぐに数千個体からなる集団を形成する。これらの集団はひとつの集合体のように振る舞い、地形に沿って(主に標高の低い場所へ)移動し、時に障害を避け他集団と合流する。個体間の誘引には視覚的・[[嗅覚]]的な信号が関与する<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Guo |first1=Xiaojiao |last2=Yu |first2=Qiaoqiao |last3=Chen |first3=Dafeng |last4=Wei |first4=Jianing |last5=Yang |first5=Pengcheng |last6=Yu |first6=Jia |last7=Wang |first7=Xianhui |last8=Kang |first8=Le |doi=10.1038/s41586-020-2610-4 |title=4-Vinylanisole is an aggregation pheromone in locusts |year=2020 |journal=Nature |volume=584 |issue=7822 |pages=584–588 |pmid=32788724 |bibcode=2020Natur.584..584G |s2cid=221106319}}</ref>。集団は太陽を基準にして移動していると推測される。彼らは移動の合間に休止して摂食し、時に数週間かけて数十キロを移動する<ref name=Dingle1996/>。 |

|||

群生相の個体は形態と発育が異なる。例えば[[サバクトビバッタ]]と[[トノサマバッタ]]では、群生相の若虫は黄色と黒の模様が強調された暗い体色となり、孤独相より長い若虫期でより大きく成長する。成虫はより大型となり、体型が通常と異なり、[[性的二形]]は弱まり、[[代謝]]速度は上昇する。成熟・繁殖開始は早まるが、繁殖力は低下する<ref name=Dingle1996/>。 |

|||

個体間の相互引力は羽化後も継続し、まとまった集団として振る舞う。群れから引き離された個体は元の群れに飛んで戻る。摂食後に群れから置き去りにされた個体は、上空を群れが通過する際に飛翔して合流する。群れ前列の個体が採食のために着地すると、他個体はその頭上を通過し、順番に着地する。地上での採食休憩は長時間におよび、周辺の植生を食べつくすと移動を再開する。その後、一時的な降雨で新緑が芽吹いた場所を見つけるまで長距離移動することもある<ref name=Dingle1996/>。 |

|||

== 分布と多様性 == |

|||

{{main|{{仮リンク|ワタリバッタの一覧|en|List of locust species}}}} |

|||

{{multiple image |

|||

|total_width=500 |

|||

|image1=SGR laying.jpg |

|||

|caption1=蝗害中に[[産卵]]する[[サバクトビバッタ]] |

|||

|image2=Locust-eggs Palestine 1930 composite coloured.jpg |

|||

|caption2=砂中のサバクトビバッタ卵嚢 |

|||

}} |

|||

南極以外の全大陸で、数種類のバッタは群れて蝗害を引き起こす<ref name=SciAm-Swarming>{{cite magazine |last1=Harmon |first1=Katherine |title=When Grasshoppers Go Biblical: Serotonin Causes Locusts to Swarm |url=http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/when-grasshoppers-go-bibl/ |magazine=[[Scientific American]] |access-date=7 April 2015 |date=30 January 2009}}</ref><ref name=Wagner>{{cite journal |author=Wagner, Alexandra M. |title=Grasshoppered: America's response to the 1874 Rocky Mountain locust invasion |url=https://history.nebraska.gov/sites/history.nebraska.gov/files/doc/publications/NH2008Grasshoppered.pdf |journal=Nebraska History |volume=89 |issue=4 |pages=154–167 |date=Winter 2008 |access-date=2 March 2020 |archive-date=15 April 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210415021930/https://history.nebraska.gov/sites/history.nebraska.gov/files/doc/publications/NH2008Grasshoppered.pdf |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |last1=Yoon|first1=Carol Kaesuk |title=Looking Back at the Days of the Locust |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2002/04/23/science/looking-back-at-the-days-of-the-locust.html |newspaper=[[The New York Times]] |access-date=1 April 2015 |date=23 April 2002}}</ref>{{efn|{{仮リンク|アメリカトビバッタ|en|Schistocerca americana}}({{snamei|Schistocerca americana}})は蝗害を引き起こさない<ref name=thomas>{{Cite journal |last=Thomas |first=M. C. |title=The American grasshopper, {{snamei|Schistocerca americana americana}} (Drury) (Orthoptera: Acrididae) |journal=Entomology Circular |number=342 |publisher=Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services |date=May 1991}}</ref>。}}。一例として、[[オーストラリアトビバッタ]]({{snamei|Chortoicetes terminifera}})はオーストラリアで蝗害の原因となる<ref name=SciAm-Swarming/>。 |

|||

[[サバクトビバッタ]]({{snamei|Schistocerca gregaria}})は広い分布域([[北アフリカ]]、[[中東]]、[[インド亜大陸]])<ref name=SciAm-Swarming/>および長距離を[[渡り|移動]]できることからよく知られている。豪雨によって生態的条件が整った後、2003年から2005年にかけて{{仮リンク|2003–2005年アフリカ蝗害|en|2003–2005 African locust outbreak|label=大規模な蝗害}}が西アフリカの大部分を襲った。最初の発生は[[モーリタニア]]、[[マリ共和国]]、[[ニジェール]]、[[スーダン]]で起こった。降雨によって群れは増殖・北上して[[モロッコ]]と[[アルジェリア]]の耕作地を襲った<ref>{{cite web |title=FAO issues Desert Locust alert: Mauritania, Niger, Sudan and other neighbouring countries at risk |url=http://www.fao.org/english/newsroom/news/2003/24019-en.html |publisher=Food and Agriculture Organization |access-date=3 July 2015 |location=Rome |date=20 October 2003 |archive-date=31 March 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170331112729/http://www.fao.org/english/newsroom/news/2003/24019-en.html |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title= Desert Locusts Plague West Africa|url=https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=4168375|publisher=NPR|work = Morning Edition|date=15 November 2004|accessdate= 2018年4月04日}}</ref>。群れはアフリカを横断し、過去50年にわたり蝗害の無かった[[エジプト]]、[[ヨルダン]]、[[イスラエル]]に達した<ref>{{cite web |title=Desert Locust Archives 2003 |url=http://www.fao.org/ag/locusts/en/archives/archive/1366/2003/index.html |publisher=Food and Agriculture Organization |access-date=3 July 2015}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Desert Locust Archives 2004 |url=http://www.fao.org/ag/locusts/en/archives/archive/1366/2004/index.html |publisher=[[Food and Agriculture Organization]] |access-date=3 July 2015}}</ref>。蝗害対策にかかった費用は1億2200万米ドル、作物への被害は250億ドルに達した<ref>{{cite web |title=The Desert Locust Outbreak in West Africa |url=http://www.oecd.org/general/thedesertlocustoutbreakinwestafrica.htm |publisher=OECD |access-date=3 July 2015 |date=23 September 2004}}</ref>。 |

|||

時に10亜種に細分される[[トノサマバッタ]]({{snamei|Locusta migratoria}})はアフリカ、アジア、[[オーストラリア]]、[[ニュージーランド]]で蝗害を引き起こすが、ヨーロッパでは希少となっている<ref name=Chapuis>{{cite journal |last=Chapuis |first=M-P. |author2=Lecoq, M. |author3=Michalakis, Y. |author4=Loiseau, A. |author5=Sword, G. A. |author6=Piry, S. |author7= Estoup, A. |title=Do outbreaks affect genetic population structure? A worldwide survey in a pest plagued by microsatellite null alleles |journal=Molecular Ecology |date=1 August 2008 |volume=17 |issue=16 |pages=3640–3653 |doi=10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03869.x |pmid=18643881|s2cid=4185861 |url=http://agritrop.cirad.fr/545307/ }}</ref>。[[2013年のマダガスカル蝗害]]では数百億個体もの群れが同年3月までに国のおよそ半分を襲った<ref>{{cite news |last=Botelho |first=Greg |title=Plague of locusts infests impoverished Madagascar |date=28 March 2013 |publisher=[[CNN]] |url=http://www.cnn.com/2013/03/27/world/africa/madagascar-locusts |access-date=29 March 2013}}</ref>。{{仮リンク|セネガルバッタ|en|Senegalese grasshopper}}({{snamei|Oedaleus senegalensis}})<ref name=Uvarov>{{cite book |last=Uvarov |first=B.P. |year=1966 |title=Grasshoppers and Locusts (Vol. 1) |publisher=Cambridge University Press |chapter=Phase polymorphism}}</ref>や{{仮リンク|アフリカイネバッタ|en|Hieroglyphus daganensis}}({{snamei|Hieroglyphus daganensis}})などのような種(いずれも[[サヘル]]原産)はしばしば蝗害のような振る舞いを見せ、群生相らしい形態に変化する<ref name=Uvarov/>。 |

|||

北米は南極以外で唯一ワタリバッタが生息しない亜大陸である。かつて[[ロッキートビバッタ]]は重大な害虫であったが、1902年に絶滅した<ref>''[[Canada's History]]'', October–November 2015, pages 43-44</ref>。1930年代、[[ダストボウル]]の最中に{{仮リンク|コウゲントビバッタ|en|Dissosteira longipennis}}({{snamei|Dissosteira longipennis}})が[[アメリカ合衆国中西部|中西部]]で蝗害を引き起こした。今日ではコウゲントビバッタは希少種となっており、北米では蝗害はもはや見られない<ref name="Wills 2018a">{{cite web |url=https://daily.jstor.org/the-long-lost-locust/ |title=The Long-Lost Locust |last= Wills |first= Matthew |

|||

|date=14 June 2018 |website= JSTOR Daily |access-date= October 5, 2020 |quote=...the High Plains locust (''Dissosteira longipennis''), which swept through the early 1930s...}}</ref><ref name="Wills 2018b">{{cite web |url=https://daily.jstor.org/the-long-lost-locust/ |title= The Long-Lost Locust |last=Wills |first= Matthew |date=14 June 2018 |website=JSTOR Daily |access-date= October 5, 2020 |quote=The High Plains locust still exists, but it's uncommon, just another innocent-looking grasshopper munching away on plants.}}</ref>。 |

|||

== ヒト・動物との関わり == |

|||

=== 古代 === |

|||

[[File:Maler der Grabkammer des Horemhab 002.jpg|thumb|[[古代エジプト]]・[[ホルエムヘブ]]王の墓に描かれたバッタ(前1422–1411年頃)]] |

|||

文献調査によって、歴史の中でどれだけ蝗害が蔓延していたかが明らかにされている。バッタは(特に風向きや天候の変化によって)突然襲来し、破滅的な結果をもたらしてきた。古代エジプト人は紀元前2470年から前2220年、墓にワタリバッタを彫っていた。エジプトでの破滅的な蝗害が聖書の『[[出エジプト記]]』に記されている<ref name=Krall453>{{cite book|author1=Krall, S.|author2=Peveling, R.|author3=Diallo, B.D. |title=New Strategies in Locust Control |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=s6ndBQiTiRAC&pg=PA453 |year=1997 |publisher=Springer Science & Business Media |isbn=978-3-7643-5442-8 |pages=453–454}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=出エジプト記(新共同訳) |at=10: 13–15 |quote=モーセがエジプトの地に杖を差し伸べると、主はまる一昼夜、東風を吹かせられた。朝になると、東風がいなごの大群を運んで来た。14 いなごは、エジプト全土を襲い、エジプトの領土全体にとどまった。このようにおびただしいいなごの大群は前にも後にもなかった。15 いなごが地の面をすべて覆ったので、地は暗くなった。いなごは地のあらゆる草、雹の害を免れた木の実をすべて食べ尽くしたので、木であれ、野の草であれ、エジプト全土のどこにも緑のものは何一つ残らなった。}} 和訳文は{{Citation |和書 |title=聖書 和英対訳 |publisher=[[日本聖書協会]] |year=2004 |isbn=4-8202-1241-9 |page=132}}より引用</ref>。インドの『[[マハーバーラタ]]』にも蝗害の記述がある<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FRzcSZPahZ0C&q=locusts+mahabharata&pg=PA93 |title=The Mahabharata |date=2010 |publisher=Penguin Books India |isbn=978-0-14-310016-4 |page=93}}</ref>。『[[イーリアス]]』は火から逃れるため蝗害に導かれて風の方へ向かう話が登場する<ref>{{cite web |author=Homer |title=Iliad 21.1 |website=Perseus Tufts |access-date=16 August 2017 |url=https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0134%3Abook%3D21%3Acard%3D1}}</ref>。コーランにも蝗害が書かれている<ref name=Showler>{{cite book |editor=John L. Capinera |year=2008 |title=Encyclopedia of Entomology |publisher=[[Springer Science+Business Media|Springer]] |isbn=978-1-4020-6242-1 |chapter=Desert locust, ''Schistocerca gregaria'' Forskål (Orthoptera: Acrididae) plagues |author= Showler, Allan T. |pages=1181–1186 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=i9ITMiiohVQC&pg=PA118}}</ref>。紀元前9世紀、中国の王朝は蝗害対策の役人を雇っていた<ref name=Spinage2012/>。[[新約聖書]]では、[[洗礼者ヨハネ]]はいなごと[[蜂蜜|野蜜]]によって荒野の飢えをしのいだとされ、また『[[ヨハネの黙示録]]』では人頭バッタが登場する<ref>{{Cite web |title=Bible Gateway passage: Revelation 9:7 - King James Version |url=https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Revelation%209%3A7&version=KJV |access-date=2021-12-26 |website=Bible Gateway}}</ref>。 |

|||

[[アリストテレス]]はワタリバッタおよびその繁殖環境について研究しており、[[リウィウス]]は紀元前203年に[[カプア]]を襲った破滅的な蝗害について記録している。彼は蝗害の後に起きた疫病について言及しており、腐敗した死体の悪臭が原因だとしている。人間の疫病を蝗害と関連付ける考えが広まっていった。311年に中国北西部で流行し、地域人口の98%が犠牲となったペストは蝗害のせいだとされたが、実際にワタリバッタの死体を食べたネズミ(および[[ノミ]])の増殖が原因かもしれない<ref name="Spinage2012">{{cite book |last=McNeill |first=William H. |title=Plagues and Peoples |publisher=Springer Science & Business Media |year=2012 |isbn=978-0-385-12122-4 |page=146}}</ref>。 |

|||

=== 近年 === |

|||

[[File:Diagrams of Locusts which swarmed over England in 1748.jpg|thumb|1748年にイングランドを襲撃したワタリバッタ、{{仮リンク|ウィリアム・ドラクール|en|William Delacour}}画を基にしたR・ホワイトの版画。{{仮リンク|トーマス・ペナント|en|Thomas Pennant}}の『ウェールズ旅行』(1781年)より]] |

|||

過去2000年にわたって、サバクトビバッタの蝗害はアフリカ、中東、ヨーロッパで散発的に見られた。他種のバッタが南北アメリカ、アジア、オーストラリアで大混乱を招いてきた。中国では、1924年間で173回の蝗害が発生している<ref name=Spinage2012/>。[[タイワンツチイナゴ]]({{snamei|Nomadacris succincta}})は18・19世紀にかけてインド・東南アジアの大害虫であったが、1908年の蝗害以降は滅多に大発生しなくなった<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.nzdl.org/gsdlmod?e=d-00000-00---off-0hdl--00-0----0-10-0---0---0direct-10---4-------0-1l--11-en-50---20-about---00-0-1-00-0-0-11-1-0utfZz-8-10&cl=CL1.10&d=HASHd1edbf77fbe3fa2e5e3da5.7.3&gc=0 |title=Bombay locust – ''Nomadacris succincta'' |work=Locust Handbook |publisher=Humanity Development Library |access-date=3 April 2015}}</ref>。 |

|||

1747年春、[[ダマスカス]]郊外を襲った蝗害によって近隣の作物および植生は食べつくされた。地元の散髪屋アフマド・アル=ブダイリー(Ahmad al-Budayri)は「黒雲のように襲来した。木々から作物に至るまですべてを覆いつくしてしまった。全能の神よ、我らを救いたまえ!」と蝗害を振り返っている<ref>{{cite book |last=Grehan |first=James |title=Twilight of the Saints:Everyday Religion in Ottoman Syria and Palestine |date=2014 |publisher=Oxford University Press |page=1}}</ref>。 |

|||

[[ロッキートビバッタ]]の絶滅は謎に包まれている。19世紀アメリカ合衆国西部の至る所およびカナダの一部で蝗害が見られた。1875年の{{仮リンク|アルバートの蝗害|en|Albert's swarm}}では、12.5兆匹のバッタが{{convert|198000|sqmi|km2}}([[カリフォルニア州]]を上回る)もの領域を覆い、重さは2750万トンに達したと推測される<ref name=diversity>{{cite web |url=http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Melanoplus_spretus.html |title=''Melanoplus spretus'', Rocky Mountain grasshopper |work=Animal Diversity Web |publisher=University of Michigan Museum of Zoology |access-date=16 April 2009}}</ref>。最後の生存個体は1902年にカナダで目撃された。近年の研究では[[ロッキー山脈]]の渓谷にあった産卵地が{{仮リンク|金鉱|en|Gold mining}}労働者の大規模な流入によって耕作され、土中の卵が破壊されたと示唆されている<ref name="Encarta">Encarta Reference Library Premium 2005 DVD. ''Rocky Mountain Locust''.</ref><ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.denver-rmn.com/millennium/0622mile.shtml |author=Ryckman, Lisa Levitt |title=The great locust mystery |newspaper=[[Rocky Mountain News]] |date=22 June 1999 |access-date=20 May 2007 |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20070228084636/http://www.denver-rmn.com/millennium/0622mile.shtml |archive-date=28 February 2007}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Lockwood |first=Jeffrey A. |year=2005 |title=Locust: the Devastating Rise and Mysterious Disappearance of the Insect that Shaped the American Frontier |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=swJWsR5CFu0C&pg=PR5 |publisher=[[Basic Books]] |isbn=978-0-465-04167-1}}</ref>。 |

|||

[[1915年のパレスチナ蝗害]]は{{仮リンク|レバノン山脈大飢饉|en|Great Famine of Mount Lebanon}}(1915年から1918年まで続き、200,000人が亡くなった)の主要な原因となった<ref name="Ghazal 2016">{{cite news |last=Ghazal |first=Rym |title=Lebanon's dark days of hunger: The Great Famine of 1915–18 |url=http://www.thenational.ae/world/middle-east/lebanons-dark-days-of-hunger-the-great-famine-of-1915-18 |access-date=24 January 2016 |publisher=The National |date=14 April 2015}}</ref><ref name="BBC 2014">{{cite news |title=Six unexpected WW1 battlegrounds |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-30098000 |access-date=24 January 2016 |work=BBC News |date=26 November 2014}}</ref>。蝗害は20世紀に入り減少したが、好条件化では発生し続けた<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/2020/02/locust-plague-climate-science-east-africa/ |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200216120605/https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/2020/02/locust-plague-climate-science-east-africa |url-status=dead |archive-date=16 February 2020 |title=A plague of locusts has descended on East Africa. Climate change may be to blame |last=Stone |first=Madeleine |date=14 February 2020 |website=National Geographic |access-date=9 March 2020}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |last=Ahmed |first=Kaamil |url=https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/mar/20/locust-crisis-poses-a-danger-to-millions-forecasters-warn|title=Locust crisis poses a danger to millions, forecasters warn |date=20 March 2020 |work=The Guardian |access-date=2020-03-21}}</ref>。 |

|||

=== 観測 === |

|||

[[File:Eugenio Morales en el Sáhara Español (1942).jpg|thumb|left|upright|[[スペイン領サハラ]]で蝗害を調査する{{仮リンク|エウヘニオ・モラレス・アガシノ|es|Eugenio Morales Agacino}}(1942年)]] |

|||

蝗害発生初期、大規模化する前の対処は大規模化した後よりも成功しやすい。個体数を低く抑える手段は実用化されているが、組織的・経済的・政治的問題は時に対策を困難にする。観測は初期の診断・駆除の鍵となる。理想的には、大規模な蝗害と化す前に放浪集団の大部分を殺虫剤で駆除できる。モロッコや[[サウジアラビア]]のような裕福な国ではこのような対策が可能かもしれないが、[[モーリタニア]]や[[イエメン]]のような近隣の貧しい国ではリソースが不足しており、増殖したバッタの群れが地域全体を脅かしうる<ref name=Showler/>。 |

|||

世界中のいくつかの組織が蝗害の脅威を観測している。近い将来に蝗害の被害を受ける可能性が高い地域へ予報を提供している。オーストラリアでは、{{仮リンク|オーストラリア蝗害委員会|en|Australian Plague Locust Commission}}がその役割を担っている<ref name="Role">{{cite web |url=http://www.daff.gov.au/animal-plant-health/locusts/role |title=Role of the Australian Plague Locust Commission |author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.--> |date=14 June 2011 |website=Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries |publisher=Commonwealth of Australia |access-date=2 April 2015 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140715013827/http://daff.gov.au/animal-plant-health/locusts/role |archive-date=15 July 2014 }}</ref>。発生しつつある蝗害への対処には大いに有効だが、他の地域からの侵入を防ぎ、監視し、防御するための明確な区域を持つという大きな強みの上に成り立っている<ref name=Krall>{{cite book |author1=Krall, S.|author2=Peveling, R.|author3=Diallo, B.D. |title=New Strategies in Locust Control |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=s6ndBQiTiRAC |year=1997 |publisher=Springer Science & Business Media |isbn=978-3-7643-5442-8 |pages=4–6}}</ref>。中央および南部アフリカでは、中南アフリカ国際蝗害管理組織(International Locust Control Organization for Central and Southern Africa)がその役割を担っている<ref name=FAOTanzania>{{cite web|title=Red Locust disaster in Eastern Africa prevented|url=http://www.fao.org/news/story/en/item/21084/icode/|publisher=Food and Agriculture Organization|access-date=1 April 2015|date=24 June 2009|archive-date=22 March 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220322192624/https://www.fao.org/news/story/en/item/21084/icode/|url-status=dead}}</ref>。西および北西アフリカでは、[[国際連合食糧農業機関]](FAO)の西部地域サバクトビバッタ管理委員会(Commission for Controlling the Desert Locust in the Western Region)と、実際に対策を実施する各国当局の協力によって対処が行われている<ref>{{cite web|title=Countries take responsibility for regional desert locust control|url=http://www.fao.org/in-action/countries-take-responsibility-for-regional-desert-locust-control/en/|publisher=FAO|access-date=2 April 2015|date=2015}}</ref>。FAOは、2500万ヘクタールの耕地が危機にさらされているコーカサスおよび中央アジアでの状況を監視している<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.fao.org/ag/locusts-CCA/en/1010/ |title=Locusts in Caucasus and Central Asia |work=Locust Watch |publisher=Food and Agriculture Organization |access-date=2 April 2015}}</ref>。2020年2月、大規模な蝗害発生を終わらせるために、[[インド]]はドローンと専用器具を用いた監視・殺虫剤散布を行うと決定した<ref>{{Cite news |url=https://www.reuters.com/article/us-india-locusts-idUSKBN20D1X9 |title=India buys drones, specialist equipment to avert new locust attack |date=2020-02-19 |work=Reuters |access-date=2020-02-20 |language=en}}</ref>。 |

|||

=== 管理 === |

|||

歴史的に、人々が蝗害から作物を守る手段はほとんどなかったが、バッタを食べることで多少は埋め合わせになっていたかもしれない。20世紀初頭までに、卵の埋まっている土を耕す、捕獲機で若虫を捕まえる、火炎放射器で駆除する、溝に落とす、ロードローラーや他の機械で押しつぶすといった防除手段が開発されてきた<ref name=Krall453/>。1950年代までに、[[有機塩化物]]の[[ディルドリン]]が非常に強力な殺虫剤だと判明したが、環境中への[[残留性有機汚染物質|残留]]や[[食物連鎖]]での{{仮リンク|生物蓄積|en|Bioaccumulation}}を理由として多くの国で禁止された<ref name=Krall453/>。 |

|||

防除が必要な際には、トラクターに搭載した噴霧器から水性接触[[殺虫剤]]を散布し、若虫を早期に駆除する。この方法は効果的だが、時間と労力がかかる<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.fao.org/ag/locusts-CCA/en/1013/ |title=Control |work=Locusts in Caucasus and Central Asia |publisher=Food and Agriculture Organization |access-date=2 April 2015}}</ref>。航空機から濃縮殺虫剤を昆虫や植生に散布するのも望ましい。航空機から接触型殺虫剤を超微量に反復散布する方法は放浪集団に対して有効であり、広大な土地を迅速に処理できる<ref name=Krall/>。その他の最新技術としては、GPS、GISツール、衛星画像による迅速なコンピューターデータ管理・分析がある<ref>{{cite web |last1=Ceccato|first1=Pietro |title=Operational Early Warning System Using Spot-Vegetation And Terra-Modis To Predict Desert Locust Outbreaks |url=http://iri.columbia.edu/~pceccato/Public-Desert-Locust/Ceccato_full.pdf |publisher=[[Food and Agriculture Organization]]|access-date=5 March 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140510014559/http://iri.columbia.edu/~pceccato/Public-Desert-Locust/Ceccato_full.pdf |archive-date=10 May 2014}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|last1=Latchininsky |first1=Alexandre V. |last2=Sivanpillai |first2=Ramesh |title=Locust Habitat Monitoring And Risk Assessment Using Remote Sensing And GIS Technologies |url=http://www.uwyo.edu/esm/faculty-and-staff/latchininsky/documents/2010-latchininsky-sivanpillai-springer.pdf |publisher=University of Wyoming |date=2010 |access-date=5 March 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151230005049/http://www.uwyo.edu/esm/faculty-and-staff/latchininsky/documents/2010-latchininsky-sivanpillai-springer.pdf |archive-date=30 December 2015 |url-status=dead }}</ref>。 |

|||

1997年、多国籍チームはアフリカ各地で蝗害抑制のための[[生物農薬]]の試験を実施した<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Lomer, C.J. |author2=Bateman, R.P. |author3=Johnson, D.L. |author4=Langewald, J. |author5=Thomas, M. |year=2001 |title=Biological Control of Locusts and Grasshoppers |journal=Annual Review of Entomology |volume=46 |pages=667–702 |doi=10.1146/annurev.ento.46.1.667 |pmid=11112183 |s2cid=7267727 |url=https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/cd09/2d6bcac45d4337866ce41318fcf79505ac79.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201108063235/https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/cd09/2d6bcac45d4337866ce41318fcf79505ac79.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-date=2020-11-08 }}</ref>。産卵地に散布された{{仮リンク|バッタカビ|en|Metarhizium acridum}}の乾燥放飼は発芽時にバッタの外骨格を貫通し、体内に侵入して死に至らしめる<ref name="Bateman ''et al.'' (1993)">{{cite journal |last1=Bateman |first1=R. P. |last2=Carey |first2=M. |last3=Moore |first3=D. |last4=Prior |first4=C. |title=The enhanced infectivity of Metarhizium flavoviride in oil formulations to desert locusts at low humidities |journal=Annals of Applied Biology |volume=122 |issue=1 |date=1993 |issn=0003-4746 |doi=10.1111/j.1744-7348.1993.tb04022.x |pages=145–152}}</ref>。菌は個体間で感染し、地域で保持されるため追加散布は不要である<ref>{{cite journal |author=Thomas M.B., Gbongboui C., Lomer C.J. |date=1996 |title=Between-season survival of the grasshopper pathogen ''Metarhizium flavoviride'' in the Sahel |journal=Biocontrol Science and Technology |volume=6 |issue=4 |pages=569–573 |doi=10.1080/09583159631208 |bibcode=1996BioST...6..569T }}</ref>。この手法は2009年に[[タンザニア]]・[[カタヴィ国立公園]]で用いられ、約10,000ヘクタールの範囲のバッタ成虫が感染した。発生は野生の[[ゾウ]]、[[カバ]]、[[キリン]]を傷つけることなく封じ込められた<ref name=FAOTanzania/>。 |

|||

<gallery mode=packed heights=160> |

|||

File:Flaming Locusts in 1915.jpg|[[1915年のパレスチナ蝗害]]で火炎放射器を準備する人々 |

|||

File:Cessna spraying red locusts in Iku Katavi NP.jpg|タンザニア・カタヴィ国立公園で{{仮リンク|アカトビバッタ|en|Red locust}}に対し散布を行う国際アカトビバッタ管理組織の[[セスナ機]](2009年) |

|||

File:CSIRO ScienceImage 1367 Locusts attacked by the fungus Metarhizium.jpg|自然発生した[[メタリジウム]]の感染で死亡したバッタ。メタリジウムは環境にやさしい生物学的防御手段である<ref>{{cite web |title=CSIRO ScienceImage 1367 Locusts attacked by the fungus Metarhizium |url=http://www.scienceimage.csiro.au/image/1367 |publisher=CSIRO |access-date=1 April 2015}}</ref>。 |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

=== モデル生物として === |

|||

ワタリバッタは大型で、飼育・繁殖も容易なことから、研究上のモデル生物として用いられる。進化生物学の研究上で、[[ショウジョウバエ属]]や[[イエバエ]]の研究で得られた結論が一般的かどうか調べるのに利用されている<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Kellogg |first1=Elizabeth A. |last2=Shaffer |first2=H. Bradley |year=1993 |title=Model Organisms in Evolutionary Studies |journal=Systematic Biology |volume=42 |issue=4 |pages=409–414 |doi=10.2307/2992481 |jstor=2992481 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Andersson |first1=Olga |last2=Hansen |first2=Steen Honoré |last3=Hellman |first3=Karin |last4=Olsen |first4=Line Rørbæk |last5=Andersson |first5=Gunnar |last6=Badolo |first6=Lassina |last7=Svenstrup |first7=Niels |last8=Nielsen |first8=Peter Aadal |title=The Grasshopper: A Novel Model for Assessing Vertebrate Brain Uptake |journal=Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics |volume=346 |issue=2 |date=2013 |issn=0022-3565 |doi=10.1124/jpet.113.205476 |pages=211–218|pmid=23671124 }}</ref>。頑丈で、飼育・繁殖も容易なことから、学校教育の実験にも適している<ref>{{cite journal |last=Scott |first=Jon |title=The locust jump: an integrated laboratory investigation |journal=Advances in Physiology Education |date=March 2005 |volume=29 |issue=1 |pages=21–26 |doi=10.1152/advan.00037.2004 |quote=The relative size and robustness of the locust make it simple to handle and ideal for such investigations. |pmid=15718379 |s2cid=27101536 |url=http://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/6ba9/b988f2edb5729c81cf3ba2bce009b444a24e.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190226094312/http://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/6ba9/b988f2edb5729c81cf3ba2bce009b444a24e.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-date=2019-02-26 }}</ref>。 |

|||

[[テルアビブ大学]]では、触覚の鋭利な[[嗅覚]]を利用して様々な技術分野で匂いの区別に用いられている<ref>{{Cite web |title=Israeli scientists develop sniffing robot with locust antennae |website=[[Reuters]] |url=https://www.reuters.com/lifestyle/science/israeli-scientists-develop-sniffing-robot-with-locust-antennae-2023-02-06/ |access-date=2024-02-19}}</ref>。 |

|||

=== 食材として === |

|||

{{see also|{{仮リンク|バッタ (コシェル)|en|Kosher locust}}}} |

|||

[[File:Skewered locusts.jpg|thumb|upright|バッタの串焼き(中国・[[北京]])]] |

|||

ワタリバッタは{{仮リンク|食材としての昆虫|en|Insects as food|label=食材}}として古くから利用されてきた。肉と見なされてきた。世界中の複数の文化で[[昆虫食]]が行われてきており、ワタリバッタは多くのアフリカ、中東、アジア諸国で高級食材と見なされている<ref>{{Cite journal |url=http://nationalzoo.si.edu/Publications/ZooGoer/2005/4/edibleinsects.cfm |title=Edible Insects |last=Fromme |first=Alison |journal=[[Smithsonian Zoogoer]] |publisher=[[Smithsonian Institution]] |year=2005 |volume=34 |issue=4 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20051111041211/http://nationalzoo.si.edu/Publications/ZooGoer/2005/4/edibleinsects.cfm|archive-date=11 November 2005 |access-date=26 April 2015}}</ref>。 |

|||

様々な調理法があるが、多くの場合揚げ物、燻製、干物にされてきた<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.livestrong.com/article/549444-the-nutritional-value-of-locusts/ |title=The Nutritional Value of Locusts |author=Dubois, Sirah |date=24 October 2011 |publisher=Livestrong.com |access-date=12 April 2015}}</ref>。[[聖書]]には[[洗礼者ヨハネ]]が荒野中でいなごと野蜜({{翻字併記|el|ἀκρίδες καὶ μέλι ἄγριον|''akrides kai meli agrion''}})を食べていたと記されている<ref>[[マルコによる福音書|マルコ]] 1:6; [[マタイによる福音書|マタイ]] 3:4</ref>。[[キャロブ]](イナゴマメ)のような[[禁欲主義|禁欲的]][[菜食主義|植物食]]の例えではないかとの考えもあるが、''akrides'' はギリシア語でいなごを意味する<ref>{{cite web |last=Brock |first=Sebastian |title=St. John the Baptist's diet – according to some early Eastern Christian sources |url=https://www.sjc.ox.ac.uk/3763/John-the-Baptists-Diet.pdf.download |publisher=St John's College, Oxford |access-date=4 May 2015 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150924102311/http://www.sjc.ox.ac.uk/3763/John-the-Baptists-Diet.pdf.download |archive-date=24 September 2015 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Kelhoffer |first1=James A. |title=Did John the Baptist eat like a former Essene? Locust-eating in the ancient Near East and at Qumran |journal=Dead Sea Discoveries |year=2004 |volume=11 |issue=3 |pages=293–314 |quote=There is no reason, however, to question the plausibility of Mark 1:6c, that John regularly ate these foods while in the wilderness. |doi=10.1163/1568517042643756 |jstor=4193332|url=http://uu.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:385556/FULLTEXT02 }}</ref>。 |

|||

[[トーラー]]はほとんどの昆虫食を禁止しているが、特定の種類のイナゴ、中でも赤、黄色または所々灰色のものを食用として認めている<ref>{{cite web |url=http://ohr.edu/ask_db/ask_main.php/19/Q1/ |title=Are locusts really Kosher?! « Ask The Rabbi « Ohr Somayach |publisher=Ohr.edu |access-date=12 April 2015}}</ref><ref name=hebblethwaite>{{cite news |title=Eating locusts: The crunchy, kosher snack taking Israel by swarm |author=Hebblethwaite, Cordelia |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-21847517 |newspaper=BBC News: Magazine |date=21 March 2013}}</ref>。[[イスラム法学]]はイナゴ食を[[ハラール]]と宣言している<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.shariahprogram.ca/eat-halal-foods/fiqh-halal-haraam-animals.shtml |title=The Fiqh of Halal and Haram Animals |publisher=Shariahprogram.ca |access-date=12 April 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150924101138/http://www.shariahprogram.ca/eat-halal-foods/fiqh-halal-haraam-animals.shtml |archive-date=24 September 2015 |url-status=dead}}</ref><ref name=hebblethwaite/>。預言者[[ムハンマド]]は行軍中、仲間らと一緒にイナゴを食べたと言われている<ref>{{cite book |title=Bukhari |at=Volume 7, Book 67 |chapter=Hunting, Slaughtering |url=http://i-cias.com/textarchive/bukhari/067.htm |access-date=8 November 2016 |quote=403: Narrated Ibn Abi Aufa: We participated with the Prophet in six or seven Ghazawat, and we used to eat locusts with him. |archive-date=3 June 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160603234224/http://i-cias.com/textarchive/bukhari/067.htm |url-status=dead }}</ref>。 |

|||

ワタリバッタはサウジアラビアを含む[[アラビア半島]]で食べられている<ref name="al-jazirah.com">{{cite web |title={{lang|ar|من المدخرات الغذائية في الماضي "الجراد" }}|url=http://www.al-jazirah.com/2001/20011202/wo1.htm|website=www.al-jazirah.com |publisher=Al-Jazirah Newspaper |access-date=8 November 2016 |date=2 December 2001}}</ref>。2014年のラマダン前後には[[カスィーム州]]などでワタリバッタの消費が急増した。多くのサウジアラビア人が健康に良いと考えているが、同国の保健省は殺虫剤の危険があると警告している<ref>{{cite web |title={{lang|ar|سوق الجراد في بريدة يشهد تداولات كبيرة والزراعة تحذرمن التسمم}} |url=http://www.ajel.sa/local/1466546|website={{lang|ar|صحيفة عاجل الإلكترونية}} |access-date=8 November 2016 |date=11 December 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160611183839/http://www.ajel.sa/local/1466546 |archive-date=11 June 2016|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.arabnews.com/news/447002 |title=People told not to eat pesticide-laced locusts |newspaper=Arab News |date=4 April 2013 |access-date=8 January 2016}}</ref>。{{仮リンク|イエメン人|en|Yemenis}}もワタリバッタを食用としており、殺虫剤を用いる政府の計画に反対している<ref>{{cite web |author1={{lang|ar|أحلام الهمداني }}|title={{lang|ar|اليمن تكافح الجراد بـ400 مليون واليمنيون مستاءون من (قطع الأرزاق) }}|url=http://www.nabanews.net/news/7921 |website=www.nabanews.net|publisher=نبأ نيوز |access-date=8 November 2016 |date=5 March 2007 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160601093524/http://www.nabanews.net/news/7921 |archive-date=1 June 2016 |url-status=dead}}</ref>。アブドゥッサラーム・シャビーニー(ʻAbd al-Salâm Shabînî)はモロッコのワタリバッタ料理のレシピについて述べている<ref name="Shabeeny1820">{{cite book |author=El Hage Abd Salam Shabeeny |title=An account of Timbuctoo and Housa: Territories in the interior of Africa |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=LYNOAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA222 |year=1820 |pages=222–|isbn=9781613106907 }}</ref>。19世紀のヨーロッパ人旅行家はアラビア、エジプト、モロッコのアラブ人がワタリバッタを売り、調理し、そして食べるさまを観察している<ref name="Robinson1835">{{cite book |author=Robinson, Edward |title=A Dictionary of the Holy Bible, for the Use of Schools and Young Persons |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mJE4AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA192 |year=1835 |publisher=Crocker and Brewster |pages=192ff}}</ref>。エジプト、[[ヨルダン川]]周辺のパレスチナ、エジプト、そしてモロッコのアラブ人はワタリバッタを食べる一方で、シリアの農民は食用としていないと報告している<ref name="Calmet1832">{{cite book |author=Augustin Calmet |title=Dictionary of the Holy Bible by Charles Taylor |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=A5pBAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA605 |year=1832 |publisher=Holdsworth and Ball |pages=604–605}}</ref>。 |

|||

ハウラーン地方(Haouran region)の貧しい[[ファッラーヒーン]]は、飢饉の際に腸と頭を取り除いたワタリバッタを食べていた一方、ベドウィンは丸のみにしていた<ref name="Calmet1832 1">{{cite book |author=Calmet, Augustin |title=Dictionary of the Holy Bible |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=v1ga4m9vIhYC&pg=PA635 |year=1832 |publisher=Crocker and Brewster |pages=635ff|isbn=9781404787964 }}</ref>。シリア人、コプト人、ギリシア人、アルメニア人および他のキリスト教徒とアラブ人自身が頻繁にワタリバッタを食べていると報告しており、あるアラブ人はヨーロッパ人旅行者に対し、好んで食べるイナゴの種類について語っている<ref>{{cite book |author=Burder, Samuel|author-link=Samuel Burder |title=Oriental Literature, Applied to the Illustration of the Sacred Scriptures – especially with reference to antiquties, traditions, and manners (etc.) |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=SJhgAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA213 |year=1822 |publisher=Longman, Hurst |page=213}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=... Description of Arabia made from Personal Observations and Information Collected on the Spot |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=fYFDAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA57 |year=1889 |pages=57ff |last=Niebuhr |first=Carsten}}</ref>。ペルシア人は{{仮リンク|反アラブ差別主義|en|Anti-Arab racism|label=反アラブ}}的な「イナゴ喰らいのアラブ人」({{翻字併記|fa|عرب ملخ خور|''Arabe malakh-khor''}})という蔑称を用いる<ref name="Rahimieh2015">{{cite book |author=Rahimieh, Nasrin |title=Iranian Culture: Representation and identity |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=JtpzCgAAQBAJ&pg=PA133 |year=2015 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-317-42935-7 |pages=133ff}}</ref><ref name="economist1">{{cite magazine |date=5 May 2012 |title=Persians v. Arabs: Same old sneers. Nationalist feeling on both sides of the Gulf is as prickly as ever |url=http://www.economist.com/node/21554238 |magazine=[[The Economist]]}} {{cite web |title=article on ''highbeam.com'' |url=https://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-288523054.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181127022449/https://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-288523054.html |archive-date=2018-11-27|accessdate= 2016年1月08日}}</ref><ref name="Majd2008">{{cite book |author=Majd, Hooman |title=The Ayatollah Begs to Differ: The paradox of modern Iran |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=1kuSfuHovwMC&pg=PA165 |date=23 September 2008 |publisher=Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group |isbn=978-0-385-52842-9 |pages=165ff}}</ref>。 |

|||

ワタリバッタは[[飼料]]あたりで生産される食用[[タンパク質]]の量がウシの5倍にもなり、また生産時に排出される[[温室効果ガス]]はウシのそれより少ない<ref>''[[Global Steak]] – Demain nos enfants mangeront des criquets'' (2010 French documentary).</ref>。{{仮リンク|飼料要求率|en|Feed conversion ratio}}は1.7 kg/kg<ref>{{cite book |last1=Collavo |first1=A. |last2=Glew |first2=R. H. |last3=Huang |first3=Y.S. |last4=Chuang |first4=L.T. |last5=Bosse |first5=R. |last6=Paoletti |first6=M.G. |editor-last=Paoletti |editor-first=M.G. |title=Ecological implications of mini-livestock: Potential of insects, rodents, frogs, and snails |publisher=Science Publishers |year=2005 |location=New Hampshire |pages=519–544 |chapter=House cricket small-scale farming}}</ref>(ウシは10 kg/kg<ref>{{cite journal |last=Smil |first=V. |date=2002 |title=Worldwide transformation of diets, burdens of meat production and opportunities for novel food proteins |journal=Enzyme and Microbial Technology |volume=30 |issue=3 |pages=305–311 |doi=10.1016/s0141-0229(01)00504-x}}</ref>)である。生体のタンパク質は成虫で100 gあたり13から28 gで、若虫は14–18 gとなる一方で、ウシは19–26 g / 100 gほどである<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.fao.org/infoods/infoods/tables-and-databases/en/ |title=Composition database for Biodiversity |edition=Version 2, BioFoodComp2 |publisher=FAO |date=10 January 2013 |access-date=1 April 2015}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Nutritional value of insects for human consumption |url=http://www.fao.org/docrep/018/i3253e/i3253e06.pdf |publisher=FAO |access-date=1 April 2015 |archive-date=4 February 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190204211732/http://www.fao.org/docrep/018/i3253e/i3253e06.pdf |url-status=dead }}</ref>。{{仮リンク|タンパク質効率|en|Protein efficiency ratio}}は低く、1.69ほどである(標準[[カゼイン]]で2.5)。100 gのサバクトビバッタには11.5 gの脂質が含まれており、うち53.3%が不飽和、コレステロールは286 mgである<ref name=AT/> A serving of 100 g of desert locust provides 11.5 g of fat, 53.5% of which is unsaturated, and 286 mg of cholesterol.<ref name=AT>{{cite journal |last1=Abul-Tarboush |first1=Hamza M. |last2=Al-Kahtani |first2=Hassan A. |last3=Aldryhim |first3=Yousif N. |last4=Asif |first4=Mohammed |date=16 December 2010 |title=Desert locust (''Schistocercsa gregaria''): Proximate composition, physiochemcial characteristics of lipids, fatty acids, and cholesterol contents and nutritional value of protein |url=http://repository.ksu.edu.sa/jspui/handle/123456789/9701 |format=Article |journal=College of Foods and Agricultural Science |publisher=King Saud University |access-date=21 January 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150122001451/http://repository.ksu.edu.sa/jspui/handle/123456789/9701 |archive-date=22 January 2015 |url-status=dead }}</ref>。脂肪酸の中では[[パルミトレイン酸]]、[[オレイン酸]]、[[リノレン酸]]が多く含まれる。[[カリウム]]、[[ナトリウム]]、[[硫黄]]、[[カルシウム]]、[[マグネシウム]]、[[鉄]]、[[鉛]]も多少含まれている<ref name=AT/>。 |

|||

== 関連項目 == |

== 関連項目 == |

||

* [[周期ゼミ]] |

|||

* [[蝗害]] |

* [[蝗害]] |

||

* [[イナゴ]] |

* [[イナゴ]] |

||

* {{仮リンク|蝗害の一覧|en|List of locust swarms}} |

|||

* {{仮リンク|オーストラリア蝗害委員会|en|Australian Plague Locust Commission}} |

|||

* {{仮リンク|LUBILOSA|en|LUBILOSA}} – ワタリバッタ研究計画 |

|||

== 注釈 == |

|||

{{Notelist}} |

|||

== 出典 == |

== 出典 == |

||

{{reflist}} |

{{reflist}} |

||

== 外部リンク == |

|||

{{Insect-stub}} |

|||

{{Commons category|Locusta}} |

|||

{{EB1911 poster|Locust}} |

|||

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20120103093939/http://richannel.org/the-christmas-lectures-2011--locusts Visual neuron of the locust], Ri Channel video, October 2011 |

|||

* [http://www.fao.org/ag/locusts/en/info/info/index.html FAO Locust Watch] |

|||

* [http://www.fao.org/AG/AGAINFO/programmes/en/empres/home.asp FAO EMPRES] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100320233905/http://www.fao.org/ag/againfo/programmes/en/empres/home.asp |date=20 March 2010 }} |

|||

* [http://www.fao.org/ag/locusts/en/activ/DLIS/eL3suite/index.html FAO eLocust3e suite] |

|||

* [https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=plantvillage.locustsurvey&hl=en eLocust3M android app] |

|||

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20070106131148/http://www.ibimet.cnr.it/Case/sahel/infocus.php?page=mpp_main&cat=mpp Desert Locust Meteorological Monitoring at Sahel Resources] |

|||

* [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o6opjbuMd5k Locust Video] |

|||

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20130825105751/http://www.encapafrica.org/documents/PEA_pestmanagement/ERITREA_LG_SEA_MAR93.doc USAID Supplemental Environmental Assessment of the Eritrean Locust Control Program ] |

|||

* [http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNACA011.pdf USAID Supplemental Environmental Assessment: Pakistan Locust Control Programs, August 1993] |

|||

* {{YouTube|id=aCE4bF_DI70|title=footage}} |

|||

* [http://www.hearthstonelegacy.com/when-the-skies-turned-to-black-the_locust-plague-of-1875.htm When The Skies Turned To Black, The Locust Plague of 1875] |

|||

{{Normdaten}} |

{{Normdaten}} |

||

{{デフォルトソート:わたりはつた}} |

{{デフォルトソート:わたりはつた}} |

||

| 17行目: | 155行目: | ||

[[Category:昆虫学]] |

[[Category:昆虫学]] |

||

[[Category:農業害虫]] |

[[Category:農業害虫]] |

||

[[Category:生物災害]] |

|||

[[Category:昆虫食]] |

|||

[[Category:昆虫の文化]] |

|||

2024年8月12日 (月) 10:07時点における版

ワタリバッタ(英語: locust[注釈 1])とは、バッタ科のバッタのうち、サバクトビバッタやトノサマバッタのように、大量発生などにより相変異を起こして群生相となることがあるものをいう。トビバッタともいう。訳語として「いなご(蝗)」が与えられることもあるが、生物学的な意味でのイナゴとは異なる。バッタとワタリバッタの分類学上の違いはなく、群生相を生じるかどうかで区別される。進化上複数回独立して群生相の獲得が生じており、少なくとも5亜科18属が知られている。

通常、これらバッタは無害で、個体数は少なく、農業上の莫大な経済的脅威とはならない。しかしながら、急速な植生の成長後に旱魃が生じると、脳内のセロトニンによって急激な変化が生じる。急速に増殖し、個体数が十分に大きくなると群生・移動的になる(渡りと形容される)。翅のない若虫は集団(band)を形成し、翅を持った成虫の群れ(swarm)となる。集団と群れはどちらも動き回り、植生を食べつくし作物を食害する。成虫は強力な飛行者であり、飛翔距離は1日100キロメートルに達することがある。農作物を食い荒らす害虫で、国際連合食糧農業機関(FAO)によると、アフガニスタンやウズベキスタン、ロシア連邦など10カ国で毎年平均870万ヘクタールの被害が出る。2003年には西アフリカ20カ国以上の1300万ヘクタールで大発生した[2]。

先史時代よりしばしば蝗害をもたらしてきたことで知られる。古代エジプトでは墓に彫られており、また『イーリアス』『マハーバーラタ』『聖書』『コーラン』にも記述されている。蝗害は作物を壊滅させ、飢饉や人々の移住を引き起こしてきた。近年では、農法の変化ワタリバッタ産卵地調査の向上により、初期段階での防除が可能となっている。伝統的な防除では地上または空中からの殺虫剤散布に頼っていたが、近年の生物的防除がより効果的である。群行動は20世紀に減少していったが、近年の調査・防除法にもかかわらず、今日でも依然存在する。気候条件が整い、警戒を怠れば蝗害が引き起こされる。

ワタリバッタは大型の昆虫であり、動物学の研究や学校教育に有用である。また食用にもなり、歴史を通して食べられてきたほか、多くの国で高級食材とされている。

バッタの群れ

| 映像外部リンク | |

|---|---|

|

|

ワタリバッタはバッタ科に属する角の短いバッタのうち、群行動を取るものを指す。これらの虫は基本単独性だが、特定の環境下では個体数が増加し、行動・環境が変化して群生相となる[3][4][5]。

ワタリバッタとバッタは分類学上では区別されない。基本的に、その種が断続的に適切な条件下で群れを形成するかどうかで定義される。英語の "locust" は群生相が形態・行動ともに変化し、未熟個体の集団から群れが発達する種を指す。変化は密度依存型表現型可塑性と説明される[6]。

これらの変化は相変異の一例であり、対蝗研究所の設立に貢献したボリス・ウヴァロフによって初めて研究・記述された[7]。当時、別種とされていたコーカサスの孤独相および群生相のワタリバッタ(Locusta migratoria と L. danica L.)について研究する中で、彼は相変異を発見した。彼は二相をそれぞれ solitaria および gregaria と命名した[8]。これらは定住型(statary)および渡り型(migratory)と呼ばれているが、厳密にいえば渡りよりは放浪に近い行動をとる。チャールズ・バレンタイン・ライリーやノーマン・クリドルがワタリバッタの研究と防除に貢献した[9][10]。

群行動は過密に対する応答である。後脚への触覚刺激増加によってセロトニンが増加する[11]。これを受けて体色が変化し、摂食量や繁殖頻度が増加する。群生相への変化は4時間以上にわたる毎分数回以上の接触によって引き起こされる[12]。巨大な群れは何十億もの個体が数千平方キロメートルの領域に広がっており、1平方キロメートルあたりの個体密度は8000万ほどにもなる(1平方マイルあたり20億個体)[13]。サバクトビバッタが出会った際、神経系からセロトニンが放出され、群行動への前段階として相互に引き付けられる[14][15][16]。

群生相の最初の集団形成は発生(outbreak)と呼ばれ、より大きな集団への合流は急増(upsurge)として知られる。別の繁殖地で急増した集団が、地域レベルで継続的に集まることで蝗害(plagues)となる[17]。発生および急増初期では、集団中の一部の個体のみが群生相となり、集団をより広い範囲へと拡散していく。時間が経過するにつれ、バッタはより群生的になり、集団はより狭い範囲へと密集していく。1966年から1969年まで続いたアフリカ・中東・アジアでのサバクトビバッタの蝗害では、2世代によって個体数は200から300奥にまで増加したが、群れの面積は100,000平方キロメートルから5,000平方キロにまで減少した[18]。

孤独相と群生相

孤独相と群生相の大きな違いとして、行動が挙げられる。群生相の若虫は早ければ2齢から互いに惹きつけ合い、すぐに数千個体からなる集団を形成する。これらの集団はひとつの集合体のように振る舞い、地形に沿って(主に標高の低い場所へ)移動し、時に障害を避け他集団と合流する。個体間の誘引には視覚的・嗅覚的な信号が関与する[19]。集団は太陽を基準にして移動していると推測される。彼らは移動の合間に休止して摂食し、時に数週間かけて数十キロを移動する[8]。

群生相の個体は形態と発育が異なる。例えばサバクトビバッタとトノサマバッタでは、群生相の若虫は黄色と黒の模様が強調された暗い体色となり、孤独相より長い若虫期でより大きく成長する。成虫はより大型となり、体型が通常と異なり、性的二形は弱まり、代謝速度は上昇する。成熟・繁殖開始は早まるが、繁殖力は低下する[8]。

個体間の相互引力は羽化後も継続し、まとまった集団として振る舞う。群れから引き離された個体は元の群れに飛んで戻る。摂食後に群れから置き去りにされた個体は、上空を群れが通過する際に飛翔して合流する。群れ前列の個体が採食のために着地すると、他個体はその頭上を通過し、順番に着地する。地上での採食休憩は長時間におよび、周辺の植生を食べつくすと移動を再開する。その後、一時的な降雨で新緑が芽吹いた場所を見つけるまで長距離移動することもある[8]。

分布と多様性

南極以外の全大陸で、数種類のバッタは群れて蝗害を引き起こす[20][21][22][注釈 2]。一例として、オーストラリアトビバッタ(Chortoicetes terminifera)はオーストラリアで蝗害の原因となる[20]。

サバクトビバッタ(Schistocerca gregaria)は広い分布域(北アフリカ、中東、インド亜大陸)[20]および長距離を移動できることからよく知られている。豪雨によって生態的条件が整った後、2003年から2005年にかけて大規模な蝗害が西アフリカの大部分を襲った。最初の発生はモーリタニア、マリ共和国、ニジェール、スーダンで起こった。降雨によって群れは増殖・北上してモロッコとアルジェリアの耕作地を襲った[24][25]。群れはアフリカを横断し、過去50年にわたり蝗害の無かったエジプト、ヨルダン、イスラエルに達した[26][27]。蝗害対策にかかった費用は1億2200万米ドル、作物への被害は250億ドルに達した[28]。

時に10亜種に細分されるトノサマバッタ(Locusta migratoria)はアフリカ、アジア、オーストラリア、ニュージーランドで蝗害を引き起こすが、ヨーロッパでは希少となっている[29]。2013年のマダガスカル蝗害では数百億個体もの群れが同年3月までに国のおよそ半分を襲った[30]。セネガルバッタ(Oedaleus senegalensis)[31]やアフリカイネバッタ(Hieroglyphus daganensis)などのような種(いずれもサヘル原産)はしばしば蝗害のような振る舞いを見せ、群生相らしい形態に変化する[31]。

北米は南極以外で唯一ワタリバッタが生息しない亜大陸である。かつてロッキートビバッタは重大な害虫であったが、1902年に絶滅した[32]。1930年代、ダストボウルの最中にコウゲントビバッタ(Dissosteira longipennis)が中西部で蝗害を引き起こした。今日ではコウゲントビバッタは希少種となっており、北米では蝗害はもはや見られない[33][34]。

ヒト・動物との関わり

古代

文献調査によって、歴史の中でどれだけ蝗害が蔓延していたかが明らかにされている。バッタは(特に風向きや天候の変化によって)突然襲来し、破滅的な結果をもたらしてきた。古代エジプト人は紀元前2470年から前2220年、墓にワタリバッタを彫っていた。エジプトでの破滅的な蝗害が聖書の『出エジプト記』に記されている[18][35]。インドの『マハーバーラタ』にも蝗害の記述がある[36]。『イーリアス』は火から逃れるため蝗害に導かれて風の方へ向かう話が登場する[37]。コーランにも蝗害が書かれている[13]。紀元前9世紀、中国の王朝は蝗害対策の役人を雇っていた[38]。新約聖書では、洗礼者ヨハネはいなごと野蜜によって荒野の飢えをしのいだとされ、また『ヨハネの黙示録』では人頭バッタが登場する[39]。

アリストテレスはワタリバッタおよびその繁殖環境について研究しており、リウィウスは紀元前203年にカプアを襲った破滅的な蝗害について記録している。彼は蝗害の後に起きた疫病について言及しており、腐敗した死体の悪臭が原因だとしている。人間の疫病を蝗害と関連付ける考えが広まっていった。311年に中国北西部で流行し、地域人口の98%が犠牲となったペストは蝗害のせいだとされたが、実際にワタリバッタの死体を食べたネズミ(およびノミ)の増殖が原因かもしれない[38]。

近年

過去2000年にわたって、サバクトビバッタの蝗害はアフリカ、中東、ヨーロッパで散発的に見られた。他種のバッタが南北アメリカ、アジア、オーストラリアで大混乱を招いてきた。中国では、1924年間で173回の蝗害が発生している[38]。タイワンツチイナゴ(Nomadacris succincta)は18・19世紀にかけてインド・東南アジアの大害虫であったが、1908年の蝗害以降は滅多に大発生しなくなった[40]。

1747年春、ダマスカス郊外を襲った蝗害によって近隣の作物および植生は食べつくされた。地元の散髪屋アフマド・アル=ブダイリー(Ahmad al-Budayri)は「黒雲のように襲来した。木々から作物に至るまですべてを覆いつくしてしまった。全能の神よ、我らを救いたまえ!」と蝗害を振り返っている[41]。

ロッキートビバッタの絶滅は謎に包まれている。19世紀アメリカ合衆国西部の至る所およびカナダの一部で蝗害が見られた。1875年のアルバートの蝗害では、12.5兆匹のバッタが198,000平方マイル (510,000 km2)(カリフォルニア州を上回る)もの領域を覆い、重さは2750万トンに達したと推測される[42]。最後の生存個体は1902年にカナダで目撃された。近年の研究ではロッキー山脈の渓谷にあった産卵地が金鉱労働者の大規模な流入によって耕作され、土中の卵が破壊されたと示唆されている[43][44][45]。

1915年のパレスチナ蝗害はレバノン山脈大飢饉(1915年から1918年まで続き、200,000人が亡くなった)の主要な原因となった[46][47]。蝗害は20世紀に入り減少したが、好条件化では発生し続けた[48][49]。

観測

蝗害発生初期、大規模化する前の対処は大規模化した後よりも成功しやすい。個体数を低く抑える手段は実用化されているが、組織的・経済的・政治的問題は時に対策を困難にする。観測は初期の診断・駆除の鍵となる。理想的には、大規模な蝗害と化す前に放浪集団の大部分を殺虫剤で駆除できる。モロッコやサウジアラビアのような裕福な国ではこのような対策が可能かもしれないが、モーリタニアやイエメンのような近隣の貧しい国ではリソースが不足しており、増殖したバッタの群れが地域全体を脅かしうる[13]。

世界中のいくつかの組織が蝗害の脅威を観測している。近い将来に蝗害の被害を受ける可能性が高い地域へ予報を提供している。オーストラリアでは、オーストラリア蝗害委員会がその役割を担っている[50]。発生しつつある蝗害への対処には大いに有効だが、他の地域からの侵入を防ぎ、監視し、防御するための明確な区域を持つという大きな強みの上に成り立っている[51]。中央および南部アフリカでは、中南アフリカ国際蝗害管理組織(International Locust Control Organization for Central and Southern Africa)がその役割を担っている[52]。西および北西アフリカでは、国際連合食糧農業機関(FAO)の西部地域サバクトビバッタ管理委員会(Commission for Controlling the Desert Locust in the Western Region)と、実際に対策を実施する各国当局の協力によって対処が行われている[53]。FAOは、2500万ヘクタールの耕地が危機にさらされているコーカサスおよび中央アジアでの状況を監視している[54]。2020年2月、大規模な蝗害発生を終わらせるために、インドはドローンと専用器具を用いた監視・殺虫剤散布を行うと決定した[55]。

管理

歴史的に、人々が蝗害から作物を守る手段はほとんどなかったが、バッタを食べることで多少は埋め合わせになっていたかもしれない。20世紀初頭までに、卵の埋まっている土を耕す、捕獲機で若虫を捕まえる、火炎放射器で駆除する、溝に落とす、ロードローラーや他の機械で押しつぶすといった防除手段が開発されてきた[18]。1950年代までに、有機塩化物のディルドリンが非常に強力な殺虫剤だと判明したが、環境中への残留や食物連鎖での生物蓄積を理由として多くの国で禁止された[18]。

防除が必要な際には、トラクターに搭載した噴霧器から水性接触殺虫剤を散布し、若虫を早期に駆除する。この方法は効果的だが、時間と労力がかかる[56]。航空機から濃縮殺虫剤を昆虫や植生に散布するのも望ましい。航空機から接触型殺虫剤を超微量に反復散布する方法は放浪集団に対して有効であり、広大な土地を迅速に処理できる[51]。その他の最新技術としては、GPS、GISツール、衛星画像による迅速なコンピューターデータ管理・分析がある[57][58]。

1997年、多国籍チームはアフリカ各地で蝗害抑制のための生物農薬の試験を実施した[59]。産卵地に散布されたバッタカビの乾燥放飼は発芽時にバッタの外骨格を貫通し、体内に侵入して死に至らしめる[60]。菌は個体間で感染し、地域で保持されるため追加散布は不要である[61]。この手法は2009年にタンザニア・カタヴィ国立公園で用いられ、約10,000ヘクタールの範囲のバッタ成虫が感染した。発生は野生のゾウ、カバ、キリンを傷つけることなく封じ込められた[52]。

-

1915年のパレスチナ蝗害で火炎放射器を準備する人々

モデル生物として

ワタリバッタは大型で、飼育・繁殖も容易なことから、研究上のモデル生物として用いられる。進化生物学の研究上で、ショウジョウバエ属やイエバエの研究で得られた結論が一般的かどうか調べるのに利用されている[63][64]。頑丈で、飼育・繁殖も容易なことから、学校教育の実験にも適している[65]。

テルアビブ大学では、触覚の鋭利な嗅覚を利用して様々な技術分野で匂いの区別に用いられている[66]。

食材として

ワタリバッタは食材として古くから利用されてきた。肉と見なされてきた。世界中の複数の文化で昆虫食が行われてきており、ワタリバッタは多くのアフリカ、中東、アジア諸国で高級食材と見なされている[67]。

様々な調理法があるが、多くの場合揚げ物、燻製、干物にされてきた[68]。聖書には洗礼者ヨハネが荒野中でいなごと野蜜(ギリシャ語: ἀκρίδες καὶ μέλι ἄγριον, ラテン文字転写: akrides kai meli agrion)を食べていたと記されている[69]。キャロブ(イナゴマメ)のような禁欲的植物食の例えではないかとの考えもあるが、akrides はギリシア語でいなごを意味する[70][71]。

トーラーはほとんどの昆虫食を禁止しているが、特定の種類のイナゴ、中でも赤、黄色または所々灰色のものを食用として認めている[72][73]。イスラム法学はイナゴ食をハラールと宣言している[74][73]。預言者ムハンマドは行軍中、仲間らと一緒にイナゴを食べたと言われている[75]。

ワタリバッタはサウジアラビアを含むアラビア半島で食べられている[76]。2014年のラマダン前後にはカスィーム州などでワタリバッタの消費が急増した。多くのサウジアラビア人が健康に良いと考えているが、同国の保健省は殺虫剤の危険があると警告している[77][78]。イエメン人もワタリバッタを食用としており、殺虫剤を用いる政府の計画に反対している[79]。アブドゥッサラーム・シャビーニー(ʻAbd al-Salâm Shabînî)はモロッコのワタリバッタ料理のレシピについて述べている[80]。19世紀のヨーロッパ人旅行家はアラビア、エジプト、モロッコのアラブ人がワタリバッタを売り、調理し、そして食べるさまを観察している[81]。エジプト、ヨルダン川周辺のパレスチナ、エジプト、そしてモロッコのアラブ人はワタリバッタを食べる一方で、シリアの農民は食用としていないと報告している[82]。

ハウラーン地方(Haouran region)の貧しいファッラーヒーンは、飢饉の際に腸と頭を取り除いたワタリバッタを食べていた一方、ベドウィンは丸のみにしていた[83]。シリア人、コプト人、ギリシア人、アルメニア人および他のキリスト教徒とアラブ人自身が頻繁にワタリバッタを食べていると報告しており、あるアラブ人はヨーロッパ人旅行者に対し、好んで食べるイナゴの種類について語っている[84][85]。ペルシア人は反アラブ的な「イナゴ喰らいのアラブ人」(ペルシア語: عرب ملخ خور, ラテン文字転写: Arabe malakh-khor)という蔑称を用いる[86][87][88]。

ワタリバッタは飼料あたりで生産される食用タンパク質の量がウシの5倍にもなり、また生産時に排出される温室効果ガスはウシのそれより少ない[89]。飼料要求率は1.7 kg/kg[90](ウシは10 kg/kg[91])である。生体のタンパク質は成虫で100 gあたり13から28 gで、若虫は14–18 gとなる一方で、ウシは19–26 g / 100 gほどである[92][93]。タンパク質効率は低く、1.69ほどである(標準カゼインで2.5)。100 gのサバクトビバッタには11.5 gの脂質が含まれており、うち53.3%が不飽和、コレステロールは286 mgである[94] A serving of 100 g of desert locust provides 11.5 g of fat, 53.5% of which is unsaturated, and 286 mg of cholesterol.[94]。脂肪酸の中ではパルミトレイン酸、オレイン酸、リノレン酸が多く含まれる。カリウム、ナトリウム、硫黄、カルシウム、マグネシウム、鉄、鉛も多少含まれている[94]。

関連項目

注釈

出典

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "locust". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ 「2020 国際植物防疫年」『日本農業新聞』2020年1月4日6面の用語解説。

- ^ Simpson, Stephen J.; Sword, Gregory A. (2008). “Locusts”. Current Biology 18 (9): R364–R366. Bibcode: 2008CBio...18.R364S. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.02.029. PMID 18460311.

- ^ “Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about locusts”. Locust watch. FAO. 1 April 2015閲覧。

- ^ “Grasshoppers”. Animal Corner. 8 April 2015時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。1 April 2015閲覧。

- ^ Pener, Meir Paul; Simpson, Stephen J. (14 October 2009). Locust Phase Polyphenism: An Update. Advances in Insect Physiology. 36 (1st ed.). Academic Press (23 September 2009発行). p. 9. ISBN 9780123814289>

- ^ Baron, Stanley (1972). “The Desert Locust”. New Scientist: 156.

- ^ a b c d Dingle, Hugh (1996). Migration: The Biology of Life on the Move. Oxford University Press. pp. 273–274. ISBN 978-0-19-535827-8

- ^ Wikisource:The Encyclopedia Americana (1920)/Riley, Charles Valentine

- ^ Holliday, N. J. (1 February 2006). “Norman Criddle: Pioneer Entomologist of the Prairies”. Manitoba History. Manitoba Historical Society. 2015年4月16日閲覧。

- ^ Morgan, James (29 January 2009). “Locust swarms 'high' on serotonin”. BBC News. オリジナルの10 October 2013時点におけるアーカイブ。 2014年3月4日閲覧。

- ^ Rogers, S. M.; Matheson, T.; Despland, E.; Dodgson, T.; Burrows, M.; Simpson, S. J. (2003). “Mechanosensory-induced behavioral gregarization in the desert locust Schistocerca gregaria”. Journal of Experimental Biology 206 (22): 3991–4002. doi:10.1242/jeb.00648. PMID 14555739.

- ^ a b c Showler, Allan T. (2008). “Desert locust, Schistocerca gregaria Forskål (Orthoptera: Acrididae) plagues”. In John L. Capinera. Encyclopedia of Entomology. Springer. pp. 1181–1186. ISBN 978-1-4020-6242-1

- ^ Stevenson, P. A. (2009). “The key to Pandora's box”. Science 323 (5914): 594–595. doi:10.1126/science.1169280. PMID 19179520.

- ^ Callaway, Ewen (29 January 2009). “Blocking 'happiness' chemical may prevent locust plagues”. New Scientist 31 January 2009閲覧。

- ^ Antsey, Michael; Rogers, Stephen; Swidbert, R.O.; Burrows, Malcolm; Simpson, S.J. (30 January 2009). “Serotonin mediates behavioral gregarization underlying swarm formation in desert locusts”. Science 323 (5914): 627–630. Bibcode: 2009Sci...323..627A. doi:10.1126/science.1165939. PMID 19179529.

- ^ Showler, Allan T. (4 March 2013). “The Desert Locust in Africa and Western Asia: Complexities of War, Politics, Perilous Terrain, and Development”. Radcliffe's IPM World Textbook. University of Minnesota. 8 April 2015時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。3 April 2015閲覧。

- ^ a b c d Krall, S.; Peveling, R.; Diallo, B.D. (1997). New Strategies in Locust Control. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 453–454. ISBN 978-3-7643-5442-8

- ^ Guo, Xiaojiao; Yu, Qiaoqiao; Chen, Dafeng; Wei, Jianing; Yang, Pengcheng; Yu, Jia; Wang, Xianhui; Kang, Le (2020). “4-Vinylanisole is an aggregation pheromone in locusts”. Nature 584 (7822): 584–588. Bibcode: 2020Natur.584..584G. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2610-4. PMID 32788724.

- ^ a b c Harmon, Katherine (30 January 2009). “When Grasshoppers Go Biblical: Serotonin Causes Locusts to Swarm”. Scientific American 7 April 2015閲覧。.

- ^ Wagner, Alexandra M. (Winter 2008). “Grasshoppered: America's response to the 1874 Rocky Mountain locust invasion”. Nebraska History 89 (4): 154–167. オリジナルの15 April 2021時点におけるアーカイブ。 2 March 2020閲覧。.

- ^ Yoon, Carol Kaesuk (23 April 2002). “Looking Back at the Days of the Locust”. The New York Times 1 April 2015閲覧。

- ^ Thomas, M. C. (May 1991). “The American grasshopper, Schistocerca americana americana (Drury) (Orthoptera: Acrididae)”. Entomology Circular (Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services) (342).

- ^ “FAO issues Desert Locust alert: Mauritania, Niger, Sudan and other neighbouring countries at risk”. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization (20 October 2003). 31 March 2017時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。3 July 2015閲覧。

- ^ “Desert Locusts Plague West Africa”. Morning Edition. NPR (15 November 2004). 2018年4月4日閲覧。

- ^ “Desert Locust Archives 2003”. Food and Agriculture Organization. 3 July 2015閲覧。

- ^ “Desert Locust Archives 2004”. Food and Agriculture Organization. 3 July 2015閲覧。

- ^ “The Desert Locust Outbreak in West Africa”. OECD (23 September 2004). 3 July 2015閲覧。

- ^ Chapuis, M-P.; Lecoq, M.; Michalakis, Y.; Loiseau, A.; Sword, G. A.; Piry, S.; Estoup, A. (1 August 2008). “Do outbreaks affect genetic population structure? A worldwide survey in a pest plagued by microsatellite null alleles”. Molecular Ecology 17 (16): 3640–3653. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03869.x. PMID 18643881.

- ^ Botelho, Greg (28 March 2013). “Plague of locusts infests impoverished Madagascar”. CNN 29 March 2013閲覧。

- ^ a b Uvarov, B.P. (1966). “Phase polymorphism”. Grasshoppers and Locusts (Vol. 1). Cambridge University Press

- ^ Canada's History, October–November 2015, pages 43-44

- ^ Wills, Matthew (14 June 2018). “The Long-Lost Locust”. JSTOR Daily. October 5, 2020閲覧。 “...the High Plains locust (Dissosteira longipennis), which swept through the early 1930s...”

- ^ Wills, Matthew (14 June 2018). “The Long-Lost Locust”. JSTOR Daily. October 5, 2020閲覧。 “The High Plains locust still exists, but it's uncommon, just another innocent-looking grasshopper munching away on plants.”

- ^ 出エジプト記(新共同訳). 10: 13–15. "モーセがエジプトの地に杖を差し伸べると、主はまる一昼夜、東風を吹かせられた。朝になると、東風がいなごの大群を運んで来た。14 いなごは、エジプト全土を襲い、エジプトの領土全体にとどまった。このようにおびただしいいなごの大群は前にも後にもなかった。15 いなごが地の面をすべて覆ったので、地は暗くなった。いなごは地のあらゆる草、雹の害を免れた木の実をすべて食べ尽くしたので、木であれ、野の草であれ、エジプト全土のどこにも緑のものは何一つ残らなった。" 和訳文は『聖書 和英対訳』日本聖書協会、2004年、132頁。ISBN 4-8202-1241-9。より引用

- ^ The Mahabharata. Penguin Books India. (2010). p. 93. ISBN 978-0-14-310016-4

- ^ Homer. “Iliad 21.1”. Perseus Tufts. 16 August 2017閲覧。

- ^ a b c McNeill, William H. (2012). Plagues and Peoples. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-385-12122-4

- ^ “Bible Gateway passage: Revelation 9:7 - King James Version”. Bible Gateway. 2021年12月26日閲覧。

- ^ “Bombay locust – Nomadacris succincta”. Locust Handbook. Humanity Development Library. 3 April 2015閲覧。

- ^ Grehan, James (2014). Twilight of the Saints:Everyday Religion in Ottoman Syria and Palestine. Oxford University Press. p. 1

- ^ “Melanoplus spretus, Rocky Mountain grasshopper”. Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. 16 April 2009閲覧。

- ^ Encarta Reference Library Premium 2005 DVD. Rocky Mountain Locust.

- ^ Ryckman, Lisa Levitt (22 June 1999). “The great locust mystery”. Rocky Mountain News. オリジナルの28 February 2007時点におけるアーカイブ。 20 May 2007閲覧。

- ^ Lockwood, Jeffrey A. (2005). Locust: the Devastating Rise and Mysterious Disappearance of the Insect that Shaped the American Frontier. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-04167-1

- ^ Ghazal, Rym (14 April 2015). “Lebanon's dark days of hunger: The Great Famine of 1915–18”. The National 24 January 2016閲覧。

- ^ “Six unexpected WW1 battlegrounds”. BBC News. (26 November 2014) 24 January 2016閲覧。

- ^ Stone, Madeleine (14 February 2020). “A plague of locusts has descended on East Africa. Climate change may be to blame”. National Geographic. 16 February 2020時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。9 March 2020閲覧。

- ^ Ahmed, Kaamil (20 March 2020). “Locust crisis poses a danger to millions, forecasters warn”. The Guardian 2020年3月21日閲覧。

- ^ “Role of the Australian Plague Locust Commission”. Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. Commonwealth of Australia (14 June 2011). 15 July 2014時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2 April 2015閲覧。

- ^ a b Krall, S.; Peveling, R.; Diallo, B.D. (1997). New Strategies in Locust Control. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 4–6. ISBN 978-3-7643-5442-8

- ^ a b “Red Locust disaster in Eastern Africa prevented”. Food and Agriculture Organization (24 June 2009). 22 March 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。1 April 2015閲覧。

- ^ “Countries take responsibility for regional desert locust control”. FAO (2015年). 2 April 2015閲覧。

- ^ “Locusts in Caucasus and Central Asia”. Locust Watch. Food and Agriculture Organization. 2 April 2015閲覧。

- ^ “India buys drones, specialist equipment to avert new locust attack” (英語). Reuters. (2020年2月19日) 2020年2月20日閲覧。

- ^ “Control”. Locusts in Caucasus and Central Asia. Food and Agriculture Organization. 2 April 2015閲覧。

- ^ “Operational Early Warning System Using Spot-Vegetation And Terra-Modis To Predict Desert Locust Outbreaks”. Food and Agriculture Organization. 10 May 2014時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。5 March 2016閲覧。

- ^ “Locust Habitat Monitoring And Risk Assessment Using Remote Sensing And GIS Technologies”. University of Wyoming (2010年). 30 December 2015時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。5 March 2016閲覧。

- ^ Lomer, C.J.; Bateman, R.P.; Johnson, D.L.; Langewald, J.; Thomas, M. (2001). “Biological Control of Locusts and Grasshoppers”. Annual Review of Entomology 46: 667–702. doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.46.1.667. PMID 11112183. オリジナルの2020-11-08時点におけるアーカイブ。.

- ^ Bateman, R. P.; Carey, M.; Moore, D.; Prior, C. (1993). “The enhanced infectivity of Metarhizium flavoviride in oil formulations to desert locusts at low humidities”. Annals of Applied Biology 122 (1): 145–152. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7348.1993.tb04022.x. ISSN 0003-4746.

- ^ Thomas M.B., Gbongboui C., Lomer C.J. (1996). “Between-season survival of the grasshopper pathogen Metarhizium flavoviride in the Sahel”. Biocontrol Science and Technology 6 (4): 569–573. Bibcode: 1996BioST...6..569T. doi:10.1080/09583159631208.

- ^ “CSIRO ScienceImage 1367 Locusts attacked by the fungus Metarhizium”. CSIRO. 1 April 2015閲覧。

- ^ Kellogg, Elizabeth A.; Shaffer, H. Bradley (1993). “Model Organisms in Evolutionary Studies”. Systematic Biology 42 (4): 409–414. doi:10.2307/2992481. JSTOR 2992481.

- ^ Andersson, Olga; Hansen, Steen Honoré; Hellman, Karin; Olsen, Line Rørbæk; Andersson, Gunnar; Badolo, Lassina; Svenstrup, Niels; Nielsen, Peter Aadal (2013). “The Grasshopper: A Novel Model for Assessing Vertebrate Brain Uptake”. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 346 (2): 211–218. doi:10.1124/jpet.113.205476. ISSN 0022-3565. PMID 23671124.

- ^ Scott, Jon (March 2005). “The locust jump: an integrated laboratory investigation”. Advances in Physiology Education 29 (1): 21–26. doi:10.1152/advan.00037.2004. PMID 15718379. オリジナルの2019-02-26時点におけるアーカイブ。. "The relative size and robustness of the locust make it simple to handle and ideal for such investigations."

- ^ “Israeli scientists develop sniffing robot with locust antennae”. Reuters. 2024年2月19日閲覧。

- ^ Fromme, Alison (2005). “Edible Insects”. Smithsonian Zoogoer (Smithsonian Institution) 34 (4). オリジナルの11 November 2005時点におけるアーカイブ。 26 April 2015閲覧。.

- ^ Dubois, Sirah (24 October 2011). “The Nutritional Value of Locusts”. Livestrong.com. 12 April 2015閲覧。

- ^ マルコ 1:6; マタイ 3:4

- ^ Brock, Sebastian. “St. John the Baptist's diet – according to some early Eastern Christian sources”. St John's College, Oxford. 24 September 2015時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。4 May 2015閲覧。

- ^ Kelhoffer, James A. (2004). “Did John the Baptist eat like a former Essene? Locust-eating in the ancient Near East and at Qumran”. Dead Sea Discoveries 11 (3): 293–314. doi:10.1163/1568517042643756. JSTOR 4193332. "There is no reason, however, to question the plausibility of Mark 1:6c, that John regularly ate these foods while in the wilderness."

- ^ “Are locusts really Kosher?! « Ask The Rabbi « Ohr Somayach”. Ohr.edu. 12 April 2015閲覧。

- ^ a b Hebblethwaite, Cordelia (21 March 2013). “Eating locusts: The crunchy, kosher snack taking Israel by swarm”. BBC News: Magazine

- ^ “The Fiqh of Halal and Haram Animals”. Shariahprogram.ca. 24 September 2015時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。12 April 2015閲覧。

- ^ “Hunting, Slaughtering”. Bukhari. Volume 7, Book 67. オリジナルの3 June 2016時点におけるアーカイブ。 8 November 2016閲覧. "403: Narrated Ibn Abi Aufa: We participated with the Prophet in six or seven Ghazawat, and we used to eat locusts with him."

- ^ “من المدخرات الغذائية في الماضي "الجراد" ”. www.al-jazirah.com. Al-Jazirah Newspaper (2 December 2001). 8 November 2016閲覧。

- ^ “سوق الجراد في بريدة يشهد تداولات كبيرة والزراعة تحذرمن التسمم”. صحيفة عاجل الإلكترونية (11 December 2012). 11 June 2016時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。8 November 2016閲覧。

- ^ “People told not to eat pesticide-laced locusts”. Arab News. (4 April 2013) 8 January 2016閲覧。

- ^ “اليمن تكافح الجراد بـ400 مليون واليمنيون مستاءون من (قطع الأرزاق) ”. www.nabanews.net. نبأ نيوز (5 March 2007). 1 June 2016時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。8 November 2016閲覧。

- ^ El Hage Abd Salam Shabeeny (1820). An account of Timbuctoo and Housa: Territories in the interior of Africa. pp. 222–. ISBN 9781613106907

- ^ Robinson, Edward (1835). A Dictionary of the Holy Bible, for the Use of Schools and Young Persons. Crocker and Brewster. pp. 192ff

- ^ Augustin Calmet (1832). Dictionary of the Holy Bible by Charles Taylor. Holdsworth and Ball. pp. 604–605

- ^ Calmet, Augustin (1832). Dictionary of the Holy Bible. Crocker and Brewster. pp. 635ff. ISBN 9781404787964

- ^ Burder, Samuel (1822). Oriental Literature, Applied to the Illustration of the Sacred Scriptures – especially with reference to antiquties, traditions, and manners (etc.). Longman, Hurst. p. 213

- ^ Niebuhr, Carsten (1889). ... Description of Arabia made from Personal Observations and Information Collected on the Spot. pp. 57ff

- ^ Rahimieh, Nasrin (2015). Iranian Culture: Representation and identity. Routledge. pp. 133ff. ISBN 978-1-317-42935-7

- ^ “Persians v. Arabs: Same old sneers. Nationalist feeling on both sides of the Gulf is as prickly as ever”. The Economist. (5 May 2012). “article on highbeam.com”. 2018年11月27日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2016年1月8日閲覧。

- ^ Majd, Hooman (23 September 2008). The Ayatollah Begs to Differ: The paradox of modern Iran. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. pp. 165ff. ISBN 978-0-385-52842-9

- ^ Global Steak – Demain nos enfants mangeront des criquets (2010 French documentary).

- ^ Collavo, A.; Glew, R. H.; Huang, Y.S.; Chuang, L.T.; Bosse, R.; Paoletti, M.G. (2005). “House cricket small-scale farming”. In Paoletti, M.G.. Ecological implications of mini-livestock: Potential of insects, rodents, frogs, and snails. New Hampshire: Science Publishers. pp. 519–544

- ^ Smil, V. (2002). “Worldwide transformation of diets, burdens of meat production and opportunities for novel food proteins”. Enzyme and Microbial Technology 30 (3): 305–311. doi:10.1016/s0141-0229(01)00504-x.

- ^ “Composition database for Biodiversity”. FAO (10 January 2013). 1 April 2015閲覧。

- ^ “Nutritional value of insects for human consumption”. FAO. 4 February 2019時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。1 April 2015閲覧。

- ^ a b c Abul-Tarboush, Hamza M.; Al-Kahtani, Hassan A.; Aldryhim, Yousif N.; Asif, Mohammed (16 December 2010). “Desert locust (Schistocercsa gregaria): Proximate composition, physiochemcial characteristics of lipids, fatty acids, and cholesterol contents and nutritional value of protein” (Article). College of Foods and Agricultural Science (King Saud University). オリジナルの22 January 2015時点におけるアーカイブ。 21 January 2015閲覧。.

外部リンク

- Visual neuron of the locust, Ri Channel video, October 2011

- FAO Locust Watch

- FAO EMPRES Archived 20 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- FAO eLocust3e suite

- eLocust3M android app

- Desert Locust Meteorological Monitoring at Sahel Resources

- Locust Video

- USAID Supplemental Environmental Assessment of the Eritrean Locust Control Program

- USAID Supplemental Environmental Assessment: Pakistan Locust Control Programs, August 1993

- footage - YouTube

- When The Skies Turned To Black, The Locust Plague of 1875

![自然発生したメタリジウムの感染で死亡したバッタ。メタリジウムは環境にやさしい生物学的防御手段である[62]。](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3b/CSIRO_ScienceImage_1367_Locusts_attacked_by_the_fungus_Metarhizium.jpg/320px-CSIRO_ScienceImage_1367_Locusts_attacked_by_the_fungus_Metarhizium.jpg)