ポリオーマウイルス科

| ポリオーマウイルス科 | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

ポリオーマウイルスが感染した大きな細胞(青、下部中央左)。尿細胞診試料

| ||||||||||||||||||

| 分類 | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| 属 | ||||||||||||||||||

ポリオーマウイルス科(ポリオーマウイルスか、Polyomaviridae)はウイルスの科の1つであり、自然宿主は主に哺乳類と鳥類である[1][2]。

2021年時点で8属117種が知られている[3]。そのうち14種がヒトに感染することが知られているが、SV40など他のウイルスも小規模ながらヒトへの感染が確認されている[4][5]。こうしたウイルスは非常に広く存在し、大部分のヒト集団では症状を引き起こさないことが一般的である[6][7]。

BKウイルスは腎臓やその他の実質臓器の移植患者における腎症と関係しており[8][9]、またJCウイルスは進行性多巣性白質脳症[10]、メルケル細胞ポリオーマウイルスはメルケル細胞癌と関係している[11]。

構造とゲノム

[編集]

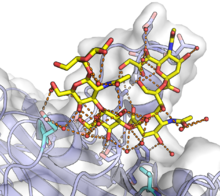

ポリオーマウイルスは非エンベロープ型二本鎖DNAウイルスであり、約5000塩基対の環状ゲノムを持つ。ゲノムは直径約40–50 nmのカプシドに詰め込まれており、カプシドは二十面体型(T=7)である[2][12]。カプシドはVP1と呼ばれるタンパク質の五量体型カプソメア72個から構成され、自己集合して閉じた二十面体を形成することができる[13]。各VP1五量体は他の2つのカプシドタンパク質VP2またはVP3のいずれか1分子と結合している[5]。

典型的なポリオーマウイルスのゲノムは5種類から9種類のタンパク質をコードしており、感染時に転写が行われる時期によってearly region(前期領域)とlate region(後期領域)と呼ばれる2つの転写領域に分けられる。各領域は宿主細胞のRNAポリメラーゼIIによって、複数の遺伝子をコードする一本のpre-mRNAとして転写される。通常、前期領域は選択的スプライシングによって産生されるラージT抗原(大型腫瘍抗原)とスモールT抗原(小型腫瘍抗原)の2つのタンパク質をコードしている。後期領域には3つのカプシド構造タンパク質VP1、VP2、VP3が含まれ、これらは選択的翻訳開始部位を利用して産生される。一部のウイルスには他の遺伝子や他の多様性が存在する。例えば、齧歯類のポリオーマウイルスにはミドルT抗原と呼ばれる3番目のタンパク質が存在し、このタンパク質によって細胞の形質転換が非常に効率的に行われる。SV40にはVP4と呼ばれるカプシドタンパク質も存在し、また一部のウイルスには後期領域から発現するアグノプロテインと呼ばれる調節タンパク質も存在する。また、ゲノムには前期領域や後期領域のプロモーター、転写開始部位、複製起点など、タンパク質をコードしない制御領域も存在する[2][5][12][15]。

複製と生活環

[編集]

ポリオーマウイルスの生活環は、宿主細胞へ進入することで開始される。ポリオーマウイルスの細胞受容体は糖鎖、一般的にはガングリオシドのシアル酸残基である。ポリオーマウイルスの宿主細胞への接着は、細胞表面のシアル化糖鎖へのVP1の結合によって媒介される[2][12][15][16]。一部のウイルスには他の細胞表面との相互作用が存在し、一例としてJCウイルスは5-HT2A受容体との相互作用が、メルケル細胞ウイルスはヘパラン硫酸との相互作用が必要であると考えられている[15][17]。しかしながら、一般的にウイルス-細胞間の相互作用は細胞表面に広く存在する分子によって媒介されており、そのため個々のウイルスで観察されるトロピズムに寄与する主要な因子ではないと考えられている[15]。細胞表面の分子への結合後、ビリオンはエンドサイトーシスされて小胞体へ移行し(これは既知の非エンベロープ型ウイルスの中では独特な挙動である[18])、そこで宿主細胞のジスルフィドイソメラーゼの作用によってウイルスのカプシド構造は破壊される[2][12][19]。

核への移行の詳細は明らかではなく、個々のポリオーマウイルスによって異なる可能性がある。完全だが歪んだ形のビリオン粒子が小胞体から細胞質へ放出されることが多く報告されており、そこでゲノムはカプシドから遊離するが、細胞質のカルシウム濃度が低さがおそらくその契機となっている[18]。ウイルス遺伝子の発現とウイルスゲノムの複製はどちらも核内で宿主細胞の装置を用いて行われる。最初に発現する前期遺伝子には少なくともスモールT抗原(ST)とラージT抗原(LT)が含まれ、1種類のmRNA鎖から選択的スプライシングによって発現する。これらのタンパク質は宿主の細胞周期を操作する機能を果たし、G1期からS期への移行の調節の異常を引き起こす。S期は宿主細胞のゲノムが複製される段階であり、ウイルスゲノムの複製には宿主細胞のDNA複製装置が必要である[2][12][15]。この調節異常の機構の詳細はウイルスによって異なり、例えばSV40のLTは宿主細胞のp53に直接結合するが、マウスポリオーマウイルスのLTは結合しない[20]。LTはウイルスゲノムの非コード制御領域(non-coding control region, NCCR)からのDNA複製を誘導する。その後、前期mRNAの発現は低下し、ウイルスカプシドタンパク質をコードする後期mRNAの発現が開始される[19]。こうした相互作用が開始されると、メルケル細胞ポリオーマウイルスなどいくつかのポリオーマウイルスのLTは発がん性を示すようになる[21]。前期遺伝子から後期遺伝子への発現の移行を調節する機構としては、前期プロモーターの抑制へのLTの関与[19]、前期mRNAに相補的な配列を持つ非終結型後期mRNAの発現[15]、調節性miRNAの発現[15]など、いくつかの機構が記載されている。後期遺伝子の発現は、宿主細胞の細胞質へのウイルスカプシドの蓄積を引き起こす。カプシドの構成要素は新たに合成されたウイルスゲノムDNAを内包するために核へ移行する。新たなビリオンはvirus factory(「ウイルス工場」)で組み立てられている可能性がある[2][12]。宿主細胞からのウイルスの放出機構はウイルスによって異なり、一部のウイルスはアグノプロテインやVP4といった、細胞からの脱出を促進するタンパク質を発現する[19]。一部のケースではカプシド化されたウイルスが高レベルに蓄積することで細胞の溶解が引き起こされ、ビリオンが放出される[15]。

ウイルスタンパク質

[編集]腫瘍抗原

[編集]ラージT抗原はウイルスの生活環の調節に重要な役割を果たしており、ウイルスDNAの複製起点に結合してDNA合成を促進する。また、ポリオーマウイルスは複製を宿主細胞の装置に依存しているため、複製が開始されるためには 宿主細胞がS期にある必要がある。またラージT抗原はいくつかの制御タンパク質に結合することで細胞のシグナル伝達経路を調節し、細胞周期の進行を促進する[22]。この作用は、がん抑制遺伝子p53やRbファミリーのメンバーの阻害[23]、そしてDNAへの結合、ATPアーゼ型ヘリカーゼやDNAポリメラーゼαとの結合、転写開始前複合体の構成因子への結合による細胞成長経路の刺激[24]という二方面からの攻撃によって行われる。この細胞周期の異常な刺激は、発がん性形質転換の強力な駆動力となる。

スモールT抗原も、細胞増殖を刺激するいくつかの細胞経路を活性化することができる。ポリオーマウイルスのスモールT抗原は共通してPP2Aを標的とする[25]。PP2AはAkt、MAPK、SAPK経路など複数の経路の重要な多サブユニット型調節因子である[26][27]。メルケル細胞ポリオーマウイルスのスモールT抗原はLT-stabilization domain(LSD)と呼ばれる固有のドメインをコードしている。LSDはE3リガーゼFBXW7に結合して阻害し、細胞由来とウイルス由来の双方のがんタンパク質を調節する[28]。SV40とは異なり、メルケル細胞ポリオーマウイルスのスモールT抗原はin vitroで齧歯類細胞を直接形質転換することができる[29]。

ミドルT抗原は、MMTV-PyMTシステムなど、がん研究のために開発されたモデル生物で利用されている。このシステムではミドルT抗原はMMTVプロモーターと共役したがん遺伝子として機能し、腫瘍を形成する組織はMMTVプロモーターによって決定される。

カプシドタンパク質

[編集]ポリオーマウイルスのカプシドは主要な構成要素であるVP1と、1つまたは2つのマイナーな構成要素であるVP2、VP3から構成される。VP1五量体は閉じた十二面体型のウイルスカプシドを形成し、カプシドの内部で各五量体はVP2またはVP3のいずれか1分子と結合している[5][30]。メルケル細胞ポリオーマウイルスなど一部のウイルスは、VP3がコードされていなかったり発現しなかったりする[31]。カプシドタンパク質はゲノムの後期領域から発現する[5]。

アグノプロテイン

[編集]アグノプロテインは、一部のポリオーマウイルスのゲノムの後期領域にコードされている小さな多機能型リン酸化タンパク質である。アグノプロテインを持つウイルスとしては、BKウイルス、JCウイルス、SV40などがある。アグノプロテインを発現するウイルスでは増殖に必要不可欠であり、ウイルスの生活環の調節、特に複製と宿主細胞からの脱出に関与していると考えられているが、正確な機構は不明である[32][33]。

分類

[編集]ポリオーマウイルスは第I群(二本鎖DNAウイルス)に属する。ポリオーマウイルスの分類法は、新たなメンバーが発見されるたびにいくつかの改訂が提唱されている。ポリオーマウイルスとパピローマウイルスは共通した構造的特徴を多く持つ一方でゲノム構成は大きく異なるが、両者は以前には共にパポバウイルス科(Papovaviridae、廃止)に分類されていた[34](Paはパピローマウイルス、Poはポリオーマウイルス、Vaはvacuolating(空胞形成)に由来する)[35]。国際ウイルス分類委員会(ICTV)によって2010年に提唱された分類では、ポリオーマウイルス科をオルソポリオーマウイルス属(Orthopolyomavirus、タイプ種: SV40)、Wukipolyomavirus属(タイプ種: KIポリオーマウイルス)、Avipolyomavirus属(タイプ種: Avian polyomavirus)の3つの属に分類することが推奨されていた[36]。

現在のICTV分類系では8属117種が認定されている。8つの属は次の通りである[3]。

- アルファポリオーマウイルス属

- Betapolyomavirus

- Deltapolyomavirus

- Epsilonpolyomavirus

- Gammapolyomavirus

- Zetapolyomavirus

- Etapolyomavirus

- Thetapolyomavirus

ヒトポリオーマウイルス

[編集]大部分のポリオーマウイルスはヒトには感染しない。2017年時点で収載されているポリオーマウイルスのうち、14種がヒトを宿主とすることが知られている[4]。一部のウイルスはヒトの疾患と関係しており、特に免疫不全状態の人物にとって重要である。メルケル細胞ウイルス(MCV)は他のヒトポリオーマウイルスからはかなり分岐しており、マウスのポリオーマウイルスと最も密接に関係している。トリコディスプレジア・スピヌローザ関連ポリオーマウイルス(TSV)はMCVと遠い関係にある。HPyV6とHPyV7はKIポリオーマウイルス、WUポリオーマウイルスと最も密接に関係している。HPyV9はafrican green monkey-derived lymphotropic polyomavirusと最も密接に関係している。14番目に記載されたLyon IARC polyomavirus[37]はアライグマのポリオーマウイルスと関係している。

ヒトポリオーマウイルスの一覧

[編集]2017年時点で次に挙げる14種のヒトを宿主とするポリオーマウイルスが同定されており、ゲノム配列の決定が行われている[4]。

| 種 | 属 | ウイルスの名称 | 略称 | NCBI RefSeq | 発見年 | 臨床的相関 | 出典 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human polyomavirus 5 | Alpha | メルケル細胞ポリオーマウイルス | MCPyV | NC_010277 | 2008 | メルケル細胞癌[5] | [38][11][39] |

| Human polyomavirus 8 | Alpha | トリコディスプレジア・スピヌローザ関連ポリオーマウイルス | TSPyV | NC_014361 | 2010 | トリコディスプレジア・スピヌローザ[5] | [40][41] |

| Human polyomavirus 9 | Alpha | ヒトポリオーマウイルス9 | HPyV9 | NC_015150 | 2011 | 知られていない | [42] |

| Human polyomavirus 12 | Alpha | Sorex araneus polyomavirus 1 | HPyV12 | NC_020890 | 2013 | 知られていない | [43] |

| Human polyomavirus 13 | Alpha | ニュージャージーポリオーマウイルス | NJPyV | NC_024118 | 2014 | 知られていない | [44] |

| Human polyomavirus 1 | Beta | BKウイルス | BKPyV | NC_001538 | 1971 | ポリオーマウイルス関連腎症、出血性膀胱炎[5] | [45] |

| Human polyomavirus 2 | Beta | JCウイルス | JCPyV | NC_001699 | 1971 | 進行性多巣性白質脳症[5] | [46] |

| Human polyomavirus 3 | Beta | KIポリオーマウイルス | KIPyV | NC_009238 | 2007 | 知られていない | [47] |

| Human polyomavirus 4 | Beta | WUポリオーマウイルス | WUPyV | NC_009539 | 2007 | 知られていない | [14] |

| Human polyomavirus 6 | Delta | ヒトポリオーマウイルス6 | HPyV6 | NC_014406 | 2010 | HPyV6 associated pruritic and dyskeratotic dermatosis (H6PD)[48] | [31] |

| Human polyomavirus 7 | Delta | ヒトポリオーマウイルス7 | HPyV7 | NC_014407 | 2010 | HPyV7関連上皮過形成[48][49][50] | [31] |

| Human polyomavirus 10 | Delta | MWポリオーマウイルス | MWPyV | NC_018102 | 2012 | 知られていない | [51][52][53] |

| Human polyomavirus 11 | Delta | STLポリオーマウイルス | STLPyV | NC_020106 | 2013 | 知られていない | [54] |

| Human polyomavirus 14 | Alpha | Lyon IARC polyomavirus | LIPyV | NC_034253.1 | 2017 | 知られていない | [55][56] |

臨床的に重要な疾患との関連に関しては、因果関係があると考えられるもののみが示されている[5][57]。

臨床的意義

[編集]ポリオーマウイルスの感染は小児や若年成人ではきわめてありふれたものである[58]。その大部分では、ほとんどまたは全く症状がみられないようである。ウイルスはほぼすべての成人で終生存続する。ヒトポリオーマウイルスによって引き起こされる疾患は免疫不全状態の人々に広くみられ、BKウイルスは腎臓やそれ以外の実質臓器の移植患者における腎症と関係しており[8][9]、JCウイルスは進行性多巣性白質脳症[10]、メルケル細胞ポリオーマウイルスはメルケル細胞癌と関係している[11]。

SV40

[編集]SV40はサルの腎臓では疾患を引き起こすことなく複製するが、実験室条件下の齧歯類ではがんを引きこす場合がある。1950年代から1960年代初頭にかけて、ポリオワクチンの汚染のために10億人を優に超える人々がSV40に曝露された可能性があり、このウイルスがヒトでがんを引き起こす懸念が生じた[59][60]。脳腫瘍、骨腫瘍、中皮腫、非ホジキンリンパ腫など、ヒトのがんの一部にSV40が存在することが報告されているが[61]、SV40の検出は多くの場合、広く存在するヒトポリオーマウイルスとの高度の交差反応性の影響を受けている[60]。ほとんどのウイルス学者はヒトのがんの原因からSV40を除外している[59][62][63]。

診断

[編集]ポリオーマウイルスの感染は無症状であったり不顕性であったりするため、その診断は常に一次感染より後に行われる。個々のウイルスに対する抗体の検出のため、抗体アッセイが広く用いられている[64]。きわめて類似したポリオーマウイルス間の識別のため、competition assayが必要となる場合が多い[65]。

進行性多巣性白質脳症においては、JCウイルスT抗原を検出するためにSV40 T抗原抗体(Pab419が広く用いられている)の交差反応性用いた組織染色が行われる。組織や脳脊髄液の生検では、ポリオーマウイルスのDNAを増幅するためにPCRが利用される。この手法ではポリオーマウイルスの検出だけでなく、どのサブタイプであるかを判別することもできる[66]。

ポリオーマウイルス関連腎症におけるポリオーマウイルスの再活性化の診断には、尿細胞診、尿や血液中のウイルス量の定量、腎生検が主要な診断技術となる[64]。腎臓や尿路でのポリオーマウイルスの再活性化は、感染細胞やビリオン、ウイルスタンパク質の尿中へのシェディングを引き起こす。こうした細胞を検査する尿細胞診によって核内へのポリオーマウイルスの封入が確認された場合、感染が診断される[67]。また、感染した人物の尿にはビリオンやウイルスDNAが含まれるため、PCRによってウイルス量の定量も行うことができる[68]。このことは血液にも当てはまる。

MCVのT抗原に対するモノクローナル抗体を用いた組織染色は、メルケル細胞癌とその他の小型類円形腫瘍との鑑別に有用である[69]。MCV抗体を検出する血液検査も開発されている。このウイルスは広くみられるものの、メルケル細胞癌の患者は無症状感染者と比較して異常に高い抗体反応を示す[7][70][71][72]。

歴史

[編集]マウスポリオーマウイルスは最初に発見されたポリオーマウイルスであり、1953年にLudwik Grossによって、耳下腺腫瘍誘導能を持つマウス白血病抽出物として報告された[73]。その病原体がウイルスであることはSarah StewartとBernice Eddyによって特定され、かつては名前を取って"SE polyoma"と呼ばれていた[74][75][76]。「ポリオーマ」(polyoma)という語は、特定の条件下で多数(poly-)の腫瘍(-oma)を作り出すウイルスの能力を指している。この名称は"meatless linguistic sandwich"("meatless"とは"polyoma"のどちらの形態素も接辞であることを指している)であり、ウイルスの生物学に対してほとんど洞察が得られないという批判もなされている。その後の研究により、大部分のポリオーマウイルスは、自然条件下では宿主に臨床的に重要な疾患を引き起こすことはほとんどないことが発見された[77]。

2017年時点で数十種のポリオーマウイルスが同定され配列決定されているが、これらは主に鳥類と哺乳類に感染する。2種のポリオーマウイルスが魚類に感染することが知られており、それぞれブラックシーバス[78]とヨーロッパヘダイ[79]に感染する。合計で14種のポリオーマウイルスがヒトに感染することが知られている[4]。

出典

[編集]- ^ “ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Polyomaviridae”. The Journal of General Virology 98 (6): 1159–1160. (June 2017). doi:10.1099/jgv.0.000839. PMC 5656788. PMID 28640744.

- ^ a b c d e f g “ICTV Report Polyomaviridae”. 2022年5月11日閲覧。

- ^ a b “Taxonomy” (英語). talk.ictvonline.org. 2022年6月4日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d “A taxonomy update for the family Polyomaviridae”. Archives of Virology 161 (6): 1739–50. (June 2016). doi:10.1007/s00705-016-2794-y. PMID 26923930.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j “A cornucopia of human polyomaviruses”. Nature Reviews. Microbiology 11 (4): 264–76. (April 2013). doi:10.1038/nrmicro2992. PMC 3928796. PMID 23474680.

- ^ “Seroepidemiology of Human Polyomaviruses in a US Population”. American Journal of Epidemiology 183 (1): 61–9. (January 2016). doi:10.1093/aje/kwv155. PMC 5006224. PMID 26667254.

- ^ a b “Seroepidemiology of human polyomaviruses”. PLOS Pathogens 5 (3): e1000363. (March 2009). doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000363. PMC 2655709. PMID 19325891.

- ^ a b “BK virus nephropathy in renal transplant recipients”. Nephrology 21 (8): 647–54. (August 2016). doi:10.1111/nep.12728. PMID 26780694.

- ^ a b “BK polyoma virus infection and renal disease in non-renal solid organ transplantation”. Clinical Kidney Journal 9 (2): 310–8. (April 2016). doi:10.1093/ckj/sfv143. PMC 4792618. PMID 26985385.

- ^ a b “Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy”. F1000Research 4: 1424. (2015). doi:10.12688/f1000research.7071.1. PMC 4754031. PMID 26918152.

- ^ a b c “Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma”. Science 319 (5866): 1096–100. (February 2008). Bibcode: 2008Sci...319.1096F. doi:10.1126/science.1152586. PMC 2740911. PMID 18202256.

- ^ “Self-assembly of purified polyomavirus capsid protein VP1”. Cell 46 (6): 895–904. (September 1986). doi:10.1016/0092-8674(86)90071-1. PMID 3019556.

- ^ a b “Identification of a novel polyomavirus from patients with acute respiratory tract infections”. PLOS Pathogens 3 (5): e64. (May 2007). doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.0030064. PMC 1864993. PMID 17480120.

- ^ a b c d e f g h International Agency for Research on Cancer (2013). “Introduction to Polyomaviruses”. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans 104: 121–131.

- ^ a b “Structural and Functional Analysis of Murine Polyomavirus Capsid Proteins Establish the Determinants of Ligand Recognition and Pathogenicity”. PLOS Pathogens 11 (10): e1005104. (October 2015). doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1005104. PMC 4608799. PMID 26474293.

- ^ “Glycosaminoglycans and sialylated glycans sequentially facilitate Merkel cell polyomavirus infectious entry”. PLOS Pathogens 7 (7): e1002161. (July 2011). doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002161. PMC 3145800. PMID 21829355.

- ^ a b “How viruses use the endoplasmic reticulum for entry, replication, and assembly”. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 5 (1): a013250. (January 2013). doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a013250. PMC 3579393. PMID 23284050.

- ^ a b c d “Update on human polyomaviruses and cancer”. Advances in Cancer Research 106: 1–51. (2010). doi:10.1016/S0065-230X(10)06001-X. ISBN 9780123747716. PMID 20399955.

- ^ “Comparisons between Murine Polyomavirus and Simian Virus 40 Show Significant Differences in Small T Antigen Function”. Journal of Virology 85 (20): 10649–10658. (2011). doi:10.1128/JVI.05034-11. PMC 3187521. PMID 21835797.

- ^ “Merkel Cell Carcinomas Arising in Autoimmune Disease Affected Patients Treated with Biologic Drugs, Including Anti-TNF”. Clinical Cancer Research 23 (14): 3929–3934. (July 2017). doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2899. PMID 28174236.

- ^ “Human polyomaviruses and brain tumors”. Brain Research. Brain Research Reviews 50 (1): 69–85. (December 2005). doi:10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.04.007. PMID 15982744.

- ^ “Polyomavirus-associated Trichodysplasia spinulosa involves hyperproliferation, pRB phosphorylation and upregulation of p16 and p21”. PLOS ONE 9 (10): e108947. (2014). Bibcode: 2014PLoSO...9j8947K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0108947. PMC 4188587. PMID 25291363.

- ^ “The T/t common exon of simian virus 40, JC, and BK polyomavirus T antigens can functionally replace the J-domain of the Escherichia coli DnaJ molecular chaperone”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 94 (8): 3679–84. (April 1997). Bibcode: 1997PNAS...94.3679K. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.8.3679. PMC 20500. PMID 9108037.

- ^ “Polyoma small and middle T antigens and SV40 small t antigen form stable complexes with protein phosphatase 2A”. Cell 60 (1): 167–76. (January 1990). doi:10.1016/0092-8674(90)90726-u. PMID 2153055.

- ^ “The interaction of SV40 small tumor antigen with protein phosphatase 2A stimulates the map kinase pathway and induces cell proliferation”. Cell 75 (5): 887–97. (December 1993). doi:10.1016/0092-8674(93)90533-V. PMID 8252625.

- ^ “Induction of cyclin D1 by simian virus 40 small tumor antigen”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 93 (23): 12861–6. (November 1996). Bibcode: 1996PNAS...9312861W. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.23.12861. PMC 24011. PMID 8917510.

- ^ “Merkel cell polyomavirus small T antigen controls viral replication and oncoprotein expression by targeting the cellular ubiquitin ligase SCFFbw7”. Cell Host & Microbe 14 (2): 125–35. (August 2013). doi:10.1016/j.chom.2013.06.008. PMC 3764649. PMID 23954152.

- ^ “Human Merkel cell polyomavirus small T antigen is an oncoprotein targeting the 4E-BP1 translation regulator”. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 121 (9): 3623–34. (September 2011). doi:10.1172/JCI46323. PMC 3163959. PMID 21841310.

- ^ “Interaction of polyomavirus internal protein VP2 with the major capsid protein VP1 and implications for participation of VP2 in viral entry” (英語). The EMBO Journal 17 (12): 3233–40. (June 1998). doi:10.1093/emboj/17.12.3233. PMC 1170661. PMID 9628860.

- ^ a b c “Merkel cell polyomavirus and two previously unknown polyomaviruses are chronically shed from human skin”. Cell Host & Microbe 7 (6): 509–15. (June 2010). doi:10.1016/j.chom.2010.05.006. PMC 2919322. PMID 20542254.

- ^ “Infection by agnoprotein-negative mutants of polyomavirus JC and SV40 results in the release of virions that are mostly deficient in DNA content”. Virology Journal 8: 255. (May 2011). doi:10.1186/1743-422X-8-255. PMC 3127838. PMID 21609431.

- ^ “Emerging From the Unknown: Structural and Functional Features of Agnoprotein of Polyomaviruses”. Journal of Cellular Physiology 231 (10): 2115–27. (October 2016). doi:10.1002/jcp.25329. PMC 5217748. PMID 26831433.

- ^ “ICTV Taxonomy Website”. 2022年6月4日閲覧。

- ^ International Agency for Research on Cancer (2013). “IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risk to Humans. Malaria and Some Polyomaviruses (SV40, BK, JC, and Merkel Cell Viruses).”. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans 104.

- ^ “Taxonomical developments in the family Polyomaviridae”. Archives of Virology 156 (9): 1627–34. (September 2011). doi:10.1007/s00705-011-1008-x. PMC 3815707. PMID 21562881.

- ^ “Isolation and characterization of a novel putative human polyomavirus”. Virology 506: 45–54. (2017). doi:10.1016/j.virol.2017.03.007. PMID 28342387.

- ^ Altman, Lawreence K. (2008年1月18日). “Virus Is Linked to a Powerful Skin Cancer”. The New York Times 2008年1月18日閲覧。

- ^ “Human Merkel cell polyomavirus infection I. MCV T antigen expression in Merkel cell carcinoma, lymphoid tissues and lymphoid tumors”. International Journal of Cancer 125 (6): 1243–9. (September 2009). doi:10.1002/ijc.24510. PMC 6388400. PMID 19499546.

- ^ “Discovery of a new human polyomavirus associated with trichodysplasia spinulosa in an immunocompromized patient”. PLOS Pathogens 6 (7): e1001024. (July 2010). doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1001024. PMC 2912394. PMID 20686659.

- ^ “The trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus: virological background and clinical implications”. APMIS 121 (8): 770–82. (August 2013). doi:10.1111/apm.12092. PMID 23593936.

- ^ “A novel human polyomavirus closely related to the african green monkey-derived lymphotropic polyomavirus”. Journal of Virology 85 (9): 4586–90. (May 2011). doi:10.1128/jvi.02602-10. PMC 3126223. PMID 21307194.

- ^ “Identification of a novel human polyomavirus in organs of the gastrointestinal tract”. PLOS ONE 8 (3): e58021. (2013). Bibcode: 2013PLoSO...858021K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0058021. PMC 3596337. PMID 23516426.

- ^ “Identification of a novel polyomavirus in a pancreatic transplant recipient with retinal blindness and vasculitic myopathy”. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 210 (10): 1595–9. (November 2014). doi:10.1093/infdis/jiu250. PMC 4334791. PMID 24795478.

- ^ “New human papovavirus (B.K.) isolated from urine after renal transplantation”. Lancet 1 (7712): 1253–7. (June 1971). doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(71)91776-4. PMID 4104714.

- ^ “Cultivation of papova-like virus from human brain with progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy”. Lancet 1 (7712): 1257–60. (June 1971). doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(71)91777-6. PMID 4104715.

- ^ “Identification of a third human polyomavirus”. Journal of Virology 81 (8): 4130–6. (April 2007). doi:10.1128/JVI.00028-07. PMC 1866148. PMID 17287263.

- ^ a b “Human polyomavirus 6 and 7 are associated with pruritic and dyskeratotic dermatoses”. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 76 (5): 932–940.e3. (May 2017). doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.11.035. PMC 5392424. PMID 28040372.

- ^ “Human polyomavirus 7-associated pruritic rash and viremia in transplant recipients”. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 211 (10): 1560–5. (May 2015). doi:10.1093/infdis/jiu524. PMC 4425822. PMID 25231015.

- ^ “Survey for human polyomaviruses in cancer”. JCI Insight 1 (2). (February 2016). doi:10.1172/jci.insight.85562. PMC 4811373. PMID 27034991.

- ^ “Identification of MW polyomavirus, a novel polyomavirus in human stool”. Journal of Virology 86 (19): 10321–6. (October 2012). doi:10.1128/JVI.01210-12. PMC 3457274. PMID 22740408.

- ^ “Complete genome sequence of a tenth human polyomavirus”. Journal of Virology 86 (19): 10887. (October 2012). doi:10.1128/JVI.01690-12. PMC 3457262. PMID 22966183.

- ^ “Discovery of a novel polyomavirus in acute diarrheal samples from children”. PLOS ONE 7 (11): e49449. (2012). Bibcode: 2012PLoSO...749449Y. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0049449. PMC 3498111. PMID 23166671.

- ^ “Discovery of STL polyomavirus, a polyomavirus of ancestral recombinant origin that encodes a unique T antigen by alternative splicing”. Virology 436 (2): 295–303. (February 2013). doi:10.1016/j.virol.2012.12.005. PMC 3693558. PMID 23276405.

- ^ Gheit, Tarik; Dutta, Sankhadeep; Oliver, Javier; Robitaille, Alexis; Hampras, Shalaka; Combes, Jean-Damien; McKay-Chopin, Sandrine; Calvez-Kelm, Florence Le et al. (2017). “Isolation and characterization of a novel putative human polyomavirus”. Virology 506: 45–54. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2017.03.007. PMID 28342387.

- ^ “Human polyomaviruses and cancer: an overview”. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 73 (suppl 1): e558s. (2018). doi:10.6061/clinics/2018/e558s. PMC 6157077. PMID 30328951.

- ^ “Human polyomaviruses in disease and cancer”. Virology 437 (2): 63–72. (March 2013). doi:10.1016/j.virol.2012.12.015. PMID 23357733.

- ^ “Prevalence of polyomavirus BK and JC infection and replication in 400 healthy blood donors”. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 199 (6): 837–46. (March 2009). doi:10.1086/597126. PMID 19434930.

- ^ a b “Is there a role for SV40 in human cancer?”. Journal of Clinical Oncology 24 (26): 4356–65. (September 2006). doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.03.7101. PMID 16963733.

- ^ a b “SV40 in human cancers--an endless tale?”. International Journal of Cancer 107 (5): 687. (December 2003). doi:10.1002/ijc.11517. PMID 14566815.

- ^ “SV40 and human tumours: myth, association or causality?”. Nature Reviews. Cancer 2 (12): 957–64. (December 2002). doi:10.1038/nrc947. PMID 12459734.

- ^ “Thirty-five year mortality following receipt of SV40- contaminated polio vaccine during the neonatal period”. British Journal of Cancer 85 (9): 1295–7. (November 2001). doi:10.1054/bjoc.2001.2065. PMC 2375249. PMID 11720463.

- ^ “SV40 and human cancer: a review of recent data”. International Journal of Cancer 120 (2): 215–23. (January 2007). doi:10.1002/ijc.22425. PMID 17131333.

- ^ a b “Polyomavirus disease in renal transplantation: review of pathological findings and diagnostic methods”. Human Pathology 36 (12): 1245–55. (December 2005). doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2005.08.009. PMID 16311117.

- ^ Viscidi, Raphael P.; Clayman, Barbara (2006). “Serological Cross Reactivity between Polyomavirus Capsids”. In Ahsan, Nasimul. Polyomaviruses and Human Diseases. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 577. pp. 73–84. doi:10.1007/0-387-32957-9_5. ISBN 978-0-387-29233-5. PMID 16626028

- ^ “Quantification of human polyomavirus JC in brain tissue and cerebrospinal fluid of patients with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy by competitive PCR”. Journal of Virological Methods 84 (1): 23–36. (January 2000). doi:10.1016/S0166-0934(99)00128-7. PMID 10644084.

- ^ “Polyomavirus infection of renal allograft recipients: from latent infection to manifest disease”. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 10 (5): 1080–9. (May 1999). doi:10.1681/ASN.V1051080. PMID 10232695.

- ^ “Quantitation of viral DNA in renal allograft tissue from patients with BK virus nephropathy”. Transplantation 74 (4): 485–8. (August 2002). doi:10.1097/00007890-200208270-00009. PMID 12352906.

- ^ “Merkel cell polyomavirus expression in merkel cell carcinomas and its absence in combined tumors and pulmonary neuroendocrine carcinomas”. The American Journal of Surgical Pathology 33 (9): 1378–85. (September 2009). doi:10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181aa30a5. PMC 2932664. PMID 19609205.

- ^ “Human Merkel cell polyomavirus infection II. MCV is a common human infection that can be detected by conformational capsid epitope immunoassays”. International Journal of Cancer 125 (6): 1250–6. (September 2009). doi:10.1002/ijc.24509. PMC 2747737. PMID 19499548.

- ^ “Quantitation of human seroresponsiveness to Merkel cell polyomavirus”. PLOS Pathogens 5 (9): e1000578. (September 2009). doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000578. PMC 2734180. PMID 19750217.

- ^ “Association of Merkel cell polyomavirus-specific antibodies with Merkel cell carcinoma”. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 101 (21): 1510–22. (November 2009). doi:10.1093/jnci/djp332. PMC 2773184. PMID 19776382.

- ^ “A filterable agent, recovered from Ak leukemic extracts, causing salivary gland carcinomas in C3H mice”. Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine 83 (2): 414–21. (June 1953). doi:10.3181/00379727-83-20376. PMID 13064287.

- ^ “Neoplasms in mice inoculated with a tumor agent carried in tissue culture”. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 20 (6): 1223–43. (June 1958). doi:10.1093/jnci/20.6.1223. PMID 13549981.

- ^ “Characteristics of the SE polyoma virus”. American Journal of Public Health and the Nation's Health 49 (11): 1486–92. (November 1959). doi:10.2105/AJPH.49.11.1486. PMC 1373056. PMID 13819251.

- ^ “Glycosaminoglycans and sialylated glycans sequentially facilitate Merkel cell polyomavirus infectious entry”. PLOS Pathogens 7 (7): e1002161. (July 2011). doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002161. PMC 3145800. PMID 21829355.

- ^ “Natural biology of polyomavirus middle T antigen”. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 65 (2): 288–318; second and third pages, table of contents. (June 2001). doi:10.1128/mmbr.65.2.288-318.2001. PMC 99028. PMID 11381103.

- ^ “Genome Sequence of a Fish-Associated Polyomavirus, Black Sea Bass (Centropristis striata) Polyomavirus 1”. Genome Announcements 3 (1): e01476-14. (January 2015). doi:10.1128/genomeA.01476-14. PMC 4319505. PMID 25635011.

- ^ “Concurrence of Iridovirus, Polyomavirus, and a Unique Member of a New Group of Fish Papillomaviruses in Lymphocystis Disease-Affected Gilthead Sea Bream”. Journal of Virology 90 (19): 8768–79. (October 2016). doi:10.1128/JVI.01369-16. PMC 5021401. PMID 27440877.