ジフテリア毒素

| tox diphtheria toxin precursor | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

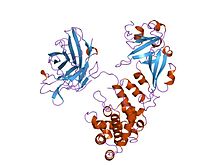

ジフテリア毒素タンパク質のリボン図 | |||||||

| 識別子 | |||||||

| 由来生物 | |||||||

| 3文字略号 | tox | ||||||

| Entrez | 2650491 | ||||||

| RefSeq (Prot) | NP_938615 | ||||||

| UniProt | P00587 | ||||||

| 他データ | |||||||

| EC番号 | 2.4.2.36 | ||||||

| 染色体 | genome: 0.19 - 0.19 Mb | ||||||

| |||||||

| Diphtheria toxin, C domain | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 識別子 | |||||||||

| 略号 | Diphtheria_C | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF02763 | ||||||||

| Pfam clan | CL0084 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR022406 | ||||||||

| SCOP | 1ddt | ||||||||

| SUPERFAMILY | 1ddt | ||||||||

| TCDB | 1.C.7 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Diphtheria toxin, T domain | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 識別子 | |||||||||

| 略号 | Diphtheria_T | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF02764 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR022405 | ||||||||

| SCOP | 1ddt | ||||||||

| SUPERFAMILY | 1ddt | ||||||||

| TCDB | 1.C.7 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Diphtheria toxin, R domain | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 識別子 | |||||||||

| 略号 | Diphtheria_R | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF01324 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR022404 | ||||||||

| SCOP | 1ddt | ||||||||

| SUPERFAMILY | 1ddt | ||||||||

| TCDB | 1.C.7 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

ジフテリア毒素(ジフテリアどくそ、英: diphtheria toxin)は、ジフテリアの原因となる病原性細菌であるジフテリア菌(コリネバクテリウム・ジフテリアエCorynebacterium diphtheriae)によって主に分泌される外毒素である。コリネバクテリウム・ウルセランスCorynebacterium ulceransや、コリネバクテリウム・シュードツベルクローシスCorynebacterium pseudotuberculosisの一部の株もこの毒素を産生する。毒素の遺伝子は、コリネファージβと呼ばれるプロファージ(宿主細菌のゲノムに挿入されたウイルス)にコードされている[1][2]。毒素はヒト細胞の細胞質に侵入し、タンパク質合成を阻害することで疾患を引き起こす[3]。

構造

[編集]ジフテリア毒素は535アミノ酸からなる1本鎖に由来し、2つのサブユニット(A、B)がジスルフィド結合によって連結された構成(A-B型毒素)をしている。Bサブユニット(2つのサブユニットの中で安定性が低い)が宿主細胞の表面へ結合し、Aサブユニット(安定性が高い)が細胞質基質へ移行する[4]。

ジフテリア毒素のホモ二量体型構造が2.5 Åの分解能で決定されており、3つのドメインからなるY字型の分子であることが明らかにされている。Aサブユニットには触媒を担うCドメインが含まれており、BサブユニットにはTドメインとRドメインが含まれている[5]。

- N末端のCドメイン(catalytic)は一般的でないβ+α型フォールドをとる[6]。Cドメインは、NAD+由来のADP-リボースを翻訳伸長因子eEF2のジフタミド残基へ転移することでタンパク質合成を遮断する[3][7]。

- 中心部のTドメイン(translocation、transmembrane)は複数のヘリックスからなるグロビン様フォールドをとるが、N末端側にさらに2つのヘリックスが存在し、最初のグロビンヘリックスに相当する部分は存在しない。このドメインは膜中でフォールドが解かれると考えられている[8]。pHの変化によるTドメインのコンフォメーション変化によってエンドソーム膜への挿入が開始され、Cドメインの細胞質基質への移行が促進される[3][7]。

- C末端のRドメイン(receptor-binding)は9本のストランドから構成され、グリークキーモチーフを有する2つのβシートが形成される。このフォールドは免疫グロブリンフォールドの下位分類である[6]。Rドメインは細胞表面受容体に結合し、受容体介在型エンドサイトーシスによって毒素の細胞内への移行を可能にする[3][7]。

機序

[編集]

ジフテリア毒素は、NAD+由来のADP-リボシル基をeEF2の非典型的アミノ酸残基であるジフタミドへ転移することで、ADPリボシル化を触媒する(EC 2.4.2.36)。ジフタミドのADPリボシル化はeEF2の不活性化をもたらし、mRNAの翻訳を阻害する[3][7]。触媒される反応は次のようなものである。

- NAD+ + ペプチド上のジフタミド ニコチンアミド + ペプチド上のN-(ADP-D-リボシル)ジフタミド

緑膿菌Pseudomonas aeruginosaのエキソトキシンAも同様の作用機序を用いる[9]。

毒性の発現には次のような段階が関与している。

- A、Bサブユニットを含む一本鎖として合成され、分泌される[10]。

- 共に分泌されるプロテアーゼによって切断され、ジスルフィド結合によって連結されたA、Bサブユニットが形成される[10]。

- 毒素が標的細胞表面のHB-EGFに結合する[11]:116。

- 複合体が宿主細胞によってエンドサイトーシスされる。

- エンドソーム内部での酸性化によって、Aサブユニットの細胞質基質への移行が誘導される[4]。

- Aサブユニットは宿主のタンパク質合成に必要なeEF2をADPリボシル化する。eEF2が不活性化されると宿主細胞はタンパク質を合成することができなくなり、死に至る[4][7]。

致死量と作用

[編集]ジフテリア毒素は非常に強力である[4]。ヒトに対する致死量は体重1 kgあたり約0.1 μgであり、心臓や肝臓の壊死によって死に至る[12]。ジフテリア毒素は心筋炎の発症とも関連している。ジフテリア性心筋炎は予防接種が不十分な小児で発生し、致死率は非常に高い[13]。

歴史

[編集]ジフテリア毒素は1888年にエミール・ルーとアレクサンドル・イェルサンによって発見された。1890年には、エミール・アドルフ・フォン・ベーリングによって弱毒菌を接種したウマの血液から抗毒素が得られた[14]。1951年Victor J. Freemanによって、毒素の遺伝子は細菌の染色体にコードされているのではなく、毒素産生株の全てに感染している溶原性ファージ(コリネファージβ)[2]にコードされていることが発見された[15][16][17]。

臨床使用

[編集]デニロイキン ジフチトクスはジフテリア毒素を利用した抗がん剤であり[18]、ジフテリア毒素のN末端の触媒ドメインとIL-2との融合タンパク質である。

Resimmuneは、皮膚T細胞リンパ腫患者に対する臨床試験が行われているイムノトキシンである。N末端の触媒ドメインが抗CD3ε抗体(UCHT1)に付加されている[19]。

研究

[編集]他のA-B型毒素と同様にジフテリア毒素は、通常は大きなタンパク質は透過しない哺乳類の細胞膜を越えて外因性タンパク質を輸送することができる。この固有の能力を利用して、毒素の触媒ドメインではなく治療用タンパク質を送達するように作り変えることができる[20][21]。

また、この毒素はジフテリア毒素の受容体(HB-EGF)を発現している特定の細胞集団を除去する目的で、神経科学やがんの研究で利用されている。通常この受容体を発現していない生物(マウスなど)において、この受容体が特定の細胞集団でのみ発現されるように改変することで、ジフテリア毒素の投与によってこの細胞集団が除去された状態を作り出すことができる[22][23]。

出典

[編集]- ^ Wagner, Patrick L.; Waldor, Matthew K. (2002-08). “Bacteriophage control of bacterial virulence”. Infection and Immunity 70 (8): 3985–3993. doi:10.1128/IAI.70.8.3985-3993.2002. ISSN 0019-9567. PMC PMC128183. PMID 12117903.

- ^ a b “Bacteriophage Involvement in Group A Streptococcal Pyrogenic Exotoxin A Production”. Journal of Bacteriology 166 (2): 623–7. (May 1986). doi:10.1128/jb.166.2.623-627.1986. PMC 214650. PMID 3009415.

- ^ a b c d e “Crystal structure of diphtheria toxin bound to nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide”. Biochemistry 35 (4): 1137–49. (January 1996). doi:10.1021/bi9520848. PMID 8573568.

- ^ a b c d “Corynebacterium Diphtheriae: Diphtheria Toxin Production”. Medical microbiology (4th ed.). Galveston, Texas: Univ. of Texas Medical Branch. (1996). ISBN 978-0-9631172-1-2. PMID 21413281

- ^ “The crystal structure of diphtheria toxin”. Nature 357 (6375): 216–22. (May 1992). Bibcode: 1992Natur.357..216C. doi:10.1038/357216a0. PMID 1589020.

- ^ a b “Crystal structure of nucleotide-free diphtheria toxin”. Biochemistry 36 (3): 481–8. (January 1997). doi:10.1021/bi962214s. PMID 9012663.

- ^ a b c d e “Refined structure of monomeric diphtheria toxin at 2.3 A resolution”. Protein Science 3 (9): 1464–75. (September 1994). doi:10.1002/pro.5560030912. PMC 2142954. PMID 7833808.

- ^ “Refined structure of dimeric diphtheria toxin at 2.0 A resolution”. Protein Science 3 (9): 1444–63. (September 1994). doi:10.1002/pro.5560030911. PMC 2142933. PMID 7833807.

- ^ Iglewski, B. H.; Liu, P. V.; Kabat, D. (1977-01). “Mechanism of action of Pseudomonas aeruginosa exotoxin Aiadenosine diphosphate-ribosylation of mammalian elongation factor 2 in vitro and in vivo”. Infection and Immunity 15 (1): 138–144. doi:10.1128/iai.15.1.138-144.1977. ISSN 0019-9567. PMC PMC421339. PMID 188760.

- ^ a b Zalman, L. S.; Wisnieski, B. J. (1984-06). “Mechanism of insertion of diphtheria toxin: peptide entry and pore size determinations”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 81 (11): 3341–3345. doi:10.1073/pnas.81.11.3341. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC PMC345503. PMID 6328510.

- ^ Gillet, Daniel; Barbier, Julien (2015). “Chapter 4: Diphtheria toxin”. The Comprehensive Sourcebook of Bacterial Protein Toxins (Fourth ed.). Elsevier. pp. 111–132. ISBN 978-0-12-800188-2

- ^ “Diphtheria toxin”. Annual Review of Biochemistry 46 (1): 69–94. (1977). doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.46.070177.000441. PMID 20040.

- ^ Varghese, Mithun J.; Ramakrishnan, Sivasubramanian; Kothari, Shyam S.; Parashar, Akhil; Juneja, Rajnish; Saxena, Anita (2013-01). “Complete heart block due to diphtheritic myocarditis in the present era”. Annals of Pediatric Cardiology 6 (1): 34–38. doi:10.4103/0974-2069.107231. ISSN 0974-2069. PMC 3634244. PMID 23626433.

- ^ “125 Jahre Diphtherieheilserum: Das Behring'sche Gold [125 years of diphtheria healing serum: Behring’s gold]” (German). Deutsches Ärzteblatt 112 (49): A-2088. (2015).

- ^ “Studies on the virulence of bacteriophage-infected strains of Corynebacterium diphtheriae”. Journal of Bacteriology 61 (6): 675–88. (June 1951). doi:10.1128/JB.61.6.675-688.1951. PMC 386063. PMID 14850426.

- ^ “Further observations on the change to virulence of bacteriophage-infected a virulent strains of Corynebacterium diphtheria”. Journal of Bacteriology 63 (3): 407–14. (March 1952). doi:10.1128/JB.63.3.407-414.1952. PMC 169283. PMID 14927573.

- ^ “Diphtheria”. Todar's Online Textbook of Bacteriology. University of Wisconsin. (2009)

- ^ “抗悪性腫瘍剤 デニロイキン ジフチトクス(遺伝子組換え)製剤”. 一般財団法人日本医薬情報センター(JAPIC). 2024年9月29日閲覧。

- ^ “Pharmacology of anti-CD3 diphtheria immunotoxin in CD3 positive T-cell lymphoma trials”. Immunotherapy of Cancer. Methods in Molecular Biology. 651. (2010). pp. 157–75. doi:10.1007/978-1-60761-786-0_10. ISBN 978-1-60761-785-3. PMID 20686966

- ^ “Efficient Delivery of Structurally Diverse Protein Cargo into Mammalian Cells by a Bacterial Toxin”. Molecular Pharmaceutics 12 (8): 2962–71. (August 2015). doi:10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.5b00233. PMID 26103531.

- ^ “Repurposing bacterial toxins for intracellular delivery of therapeutic proteins”. Biochemical Pharmacology 142: 13–20. (October 2017). doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2017.04.009. PMID 28408344.

- ^ “Selective erasure of a fear memory”. Science 323 (5920): 1492–6. (March 2009). Bibcode: 2009Sci...323.1492H. doi:10.1126/science.1164139. PMID 19286560.

- ^ “Investigating Tumor Heterogeneity in Mouse Models”. Annual Review of Cancer Biology 4 (1): 99–119. (2020). doi:10.1146/annurev-cancerbio-030419-033413. PMC 8218894. PMID 34164589.

外部リンク

[編集]- Diphtheria Toxin - MeSH・アメリカ国立医学図書館・生命科学用語シソーラス