アミロイド前駆体タンパク質

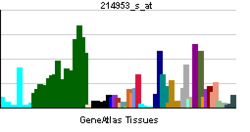

アミロイド前駆体タンパク質(アミロイドぜんくたいタンパクしつ、英: amyloid precursor protein、略称: APP)またはアミロイドβ前駆体タンパク質は、多くの組織で発現している内在性膜タンパク質で、神経細胞のシナプスに濃縮されている。主要な機能は未知であるが、シナプス形成[5]、神経可塑性[6]、抗菌活性[7]、鉄排出[8]の調節因子であると示唆されている。APPは、タンパク質分解によって形成されるアミロイドβ(Aβ)の前駆体として最もよく知られている。Aβは37–49アミノ酸残基からなるポリペプチドで、アミロイド型のAβはアルツハイマー病患者の脳に存在するアミロイド斑の主要な構成要素である。

遺伝子

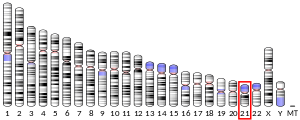

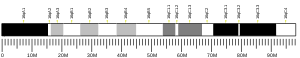

[編集]APPは進化的に古くから存在し、高度に保存されたタンパク質である[9]。ヒトのAPPをコードする遺伝子は21番染色体に位置し、290 kbにわたる18のエクソンからなる[10][11]。ヒトでは、選択的スプライシングによるアイソフォームがいくつか観察されており、アミノ酸長は639–770アミノ酸の範囲である。神経細胞では特定のアイソフォームが選択的に発現しており、アイソフォームの比率の変化はアルツハイマー病と関係している[12]。APPに相同なタンパク質は、ショウジョウバエDrosophila、線虫Caenorhabditis elegans[13]、そしてすべての哺乳類[14]で同定されている。タンパク質のAβ領域は膜貫通ドメインに位置し、種間での保存性ははっきりせず、APPの天然状態での生物学的機能との明確な関係もみられない[14]。

Aβ生成領域を含むAPPの重要領域の変異は、アルツハイマー病に対する家族性の感受性を引き起こす[15][16][17]。例えば、Aβ領域の外側のいくつかの変異は家族性アルツハイマー病と関係しており、Aβの産生が劇的に増加することが判明している[18]。

APP遺伝子のA673T変異はアルツハイマー病に対する保護効果がある。この置換はβ-セクレターゼ切断部位に近接しており、in vitroではAβの形成は40%減少する[19]。

構造

[編集]

APPの配列には、大部分が独立してフォールディングを行う、明確な構造ドメインが多数同定されている。細胞外領域は細胞内領域よりもずっと大きく、E1ドメインとE2ドメインに分けられ、両者は酸性ドメイン(AcD)によって連結されている。E1は成長因子様ドメイン(GFLD)と銅結合ドメイン(CuBD)の2つのサブドメインからなり、両者は密接に相互作用している[21]。セリンプロテアーゼ阻害因子ドメインがAcDとE2ドメインの間に存在するが、脳で発現しているアイソフォームには存在しない[22]。APPの完全な結晶構造は解かれていないが、個々のドメインの結晶化には成功しており、GFLD[23]、CuBD[24]、完全なE1ドメイン[24]とE2ドメイン[20]の構造が得られている。

翻訳後のプロセシング

[編集]APPは、グリコシル化、リン酸化、シアル酸化、チロシン硫酸化を含む広範囲の翻訳後修飾を受けるとともに、多くのタイプのタンパク質分解によるプロセシングによってペプチド断片が作り出される[25]。一般的に切断はセクレターゼファミリーのプロテアーゼによって行われ、α-セクレターゼとβ-セクレターゼはともに細胞外ドメインをほぼ完全に切除する。その結果、アポトーシスと関係している可能性のある、膜に固定されたC末端フラグメントが生じる[14]。β-セクレターゼによる切断後、γ-セクレターゼによって膜貫通ドメイン内で切断されることでAβフラグメントが形成される。γ-セクレターゼは複数のサブユニットからなる巨大複合体であり、その構成要素は完全には特定されていないものの、アルツハイマー病の主要な遺伝性危険因子として同定されているプレセニリンが含まれている[26]。

APPのアミロイド形成性プロセシングは脂質ラフトの存在と関係している。APP分子が膜の脂質ラフト領域に存在するときにはβ-セクレターゼがAPPにアクセスしやすくそのため切断を行いやすくなるが、APPが脂質ラフト外に存在するときには非アミロイド形成性のα-セクレターゼによって切断されやすい[27]。γ-セクレターゼの活性も脂質ラフトと関係している[28]。コレステロールに脂質ラフトを維持する役割があることは、高コレステロールとアポリポプロテインEの遺伝子型がアルツハイマー病の主要な危険因子であるという観察結果の説明となる[29]。

生物学的機能

[編集]APPの天然状態での生物学的役割はアルツハイマー病研究において関心が高いものの、未解明の部分が多い。

シナプス形成と修復

[編集]APPの役割として最もよく実証されているのは、シナプスの形成と修復である[5]。APPの発現は神経細胞の分化の過程そして神経損傷後にアップレギュレーションされる。細胞シグナル伝達、長期増強、細胞接着における役割が提唱されているが、それらを支持する研究は限られている[14]。特に、翻訳後のプロセシングの類似性から、Notchシグナリングとの比較が行われている[30]。

APPのノックアウトマウスは生存可能であり、一般的な神経消失を伴わない長期増強の障害と記憶消失を含む、比較的軽微な表現型を示す[31]。一方、APPの発現をアップレギュレーションしたトランスジェニックマウスも長期増強の障害を示すことが報告されている[32]。

論理的な推論としては、アルツハイマー病ではAβが過剰に蓄積しているため、その前駆体であるAPPも同様に増加していると考えられる。しかしながら、アミロイド斑に近接する神経細胞体のAPPの含有量は少ない[33]。このAPPの欠乏は、切断の増加よりむしろ産生の減少によるものであることがデータからは示唆される。神経細胞におけるAPPの喪失は、認知症に寄与する生理学的な機能欠損に影響を与えている可能性がある。

体細胞組換え

[編集]ヒトの脳の神経細胞では、APPをコードする遺伝子で高頻度の体細胞組換えが生じている[34]。孤発性アルツハイマー病患者の神経細胞では、健康な人の神経細胞よりも、体細胞組換えによるAPP遺伝子の多様性が増大している[34]。

順行性軸索輸送

[編集]神経細胞の細胞体で合成された分子は、末端のシナプスへ輸送を行う必要がある。この輸送は、速い順行性輸送(fast anterograde transport)によって行われる。APPは積み荷とキネシンとの相互作用を媒介し、この輸送を促進することが示されている。具体的には、細胞質側のC末端側の15アミノ酸の短いペプチド配列がモータータンパク質との相互作用に必要とされる[35]。APPとキネシンの間の相互作用はAPPのペプチド配列特異的であり、ペプチドを付加した蛍光ビーズを用いた輸送実験では、APPの15アミノ酸が付加されたビーズは輸送されたが、代わりにグリシンのみが付加されたビーズや他のペプチドが付加されたビーズは運動性を持たなかった[36]。

鉄排出

[編集]マウスでの研究によってアルツハイマー病の異なる面が明らかにされた。APPはセルロプラスミンに似たフェロキシダーゼ活性を持ち、フェロポーチンとの相互作用によって鉄の排出を促進することが判明した。この活性は、アルツハイマー病では蓄積したAβにトラップされた亜鉛によってブロックされるようである[8]。APPのmRNAの5'UTRには鉄応答性エレメント(IRE)が存在し、一塩基多型によって翻訳に異常が生じることが示されている[37]。

一方、APPのE2ドメインがフェロキシダーゼ活性を持ち、Fe(II)の排出を促進するという仮説は、E2ドメインに提唱された部位はフェロキシダーゼ活性を持たないことから、不正確である可能性がある[38][39]。

APPはE2ドメイン内でフェロキシダーゼ活性を持たないため、APPによって調節されるフェロポーチンからの鉄の排出機構に対して精査が行われている。あるモデルは、APPは鉄排出タンパク質フェロポーチンの細胞膜中での安定化作用をもち、それによって膜中のフェロポーチンの総数が増加していることを示唆している。鉄輸送体はその後、哺乳類の既知のフェロキシダーゼ(セルロプラスミンやヘファエスチン)によって活性化される[40]。

ホルモンによる調節

[編集]APPとそれに関係するすべてのセクレターゼが発生初期に発現しており、生殖内分泌に重要な役割を果たしている。セクレターゼによるプロセシングの差によって、ヒト胚性幹細胞(hESC)の増殖や、神経前駆細胞(NPC)への分化が調節されている。妊娠ホルモンであるヒト絨毛性ゴナドトロピン(hCG)はAPPの発現とhESCの増殖を増加させるが[41]、プロゲステロンはAPPのプロセシングを非アミロイド形成性経路へ差し向け、hESCのNPCへの分化を促進する[42][43][44]。

APPやその切断産物が、分裂期を過ぎたの神経細胞の増殖や分化を促進することはない。むしろ、分裂期を過ぎた神経細胞での野生型または変異型APPの過剰発現は、細胞周期の再進行後にアポトーシスによる細胞死を誘導する[45]。男女ともに更年期における性ホルモン(プロゲステロンを含む)の喪失と黄体形成ホルモン(成人でhCGに相当する)の上昇は、アミロイドβの産生を駆動し[46]、分裂期を過ぎた神経細胞の細胞周期を再進行させると考えられている。

相互作用

[編集]アミロイド前駆体タンパク質は次に挙げる因子と相互作用することが示されている

APPは、アルツハイマー病を含む多数の脳疾患に関係しているタンパク質であるリーリンとも相互作用する[67]。

出典

[編集]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000142192 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000022892 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ Human PubMed Reference:

- ^ Mouse PubMed Reference:

- ^ a b “Synapse formation and function is modulated by the amyloid precursor protein”. The Journal of Neuroscience 26 (27): 7212–21. (Jul 2006). doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1450-06.2006. PMID 16822978.

- ^ “Roles of amyloid precursor protein and its fragments in regulating neural activity, plasticity and memory”. Progress in Neurobiology 70 (1): 1–32. (May 2003). doi:10.1016/S0301-0082(03)00089-3. PMID 12927332.

- ^ “The antimicrobial protection hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease”. Alzheimer's & Dementia 14 (12): 1602-1614. (2018). doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2018.06.3040. PMID 30314800.

- ^ a b “Iron-export ferroxidase activity of β-amyloid precursor protein is inhibited by zinc in Alzheimer's disease”. Cell 142 (6): 857–67. (Sep 2010). doi:10.1016/j.cell.2010.08.014. PMC 2943017. PMID 20817278.

- ^ “Origins of amyloid-β”. BMC Genomics 14 (1): 290. (April 2013). doi:10.1186/1471-2164-14-290. PMC 3660159. PMID 23627794.

- ^ “Genomic organization of the human amyloid beta-protein precursor gene”. Gene 87 (2): 257–63. (Mar 1990). doi:10.1016/0378-1119(90)90310-N. PMID 2110105.

- ^ “Introduction and expression of the 400 kilobase amyloid precursor protein gene in transgenic mice [corrected]”. Nature Genetics 5 (1): 22–30. (Sep 1993). doi:10.1038/ng0993-22. PMID 8220418.

- ^ “Expression of APP pathway mRNAs and proteins in Alzheimer's disease”. Brain Research 1161: 116–23. (Aug 2007). doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2007.05.050. PMID 17586478.

- ^ Ewald, Collin Y.; Li, Chris (2012-04-01). “Caenorhabditis elegans as a model organism to study APP function” (英語). Experimental Brain Research 217 (3–4): 397–411. doi:10.1007/s00221-011-2905-7. ISSN 0014-4819. PMC 3746071. PMID 22038715.

- ^ a b c d “The amyloid precursor protein: beyond amyloid”. Molecular Neurodegeneration 1 (1): 5. (2006). doi:10.1186/1750-1326-1-5. PMC 1538601. PMID 16930452.

- ^ “Segregation of a missense mutation in the amyloid precursor protein gene with familial Alzheimer's disease”. Nature 349 (6311): 704–6. (Feb 1991). doi:10.1038/349704a0. PMID 1671712.

- ^ “A mutation in the amyloid precursor protein associated with hereditary Alzheimer's disease”. Science 254 (5028): 97–9. (Oct 1991). doi:10.1126/science.1925564. PMID 1925564.

- ^ “Early-onset Alzheimer's disease caused by mutations at codon 717 of the beta-amyloid precursor protein gene”. Nature 353 (6347): 844–6. (Oct 1991). doi:10.1038/353844a0. PMID 1944558.

- ^ “Mutation of the beta-amyloid precursor protein in familial Alzheimer's disease increases beta-protein production”. Nature 360 (6405): 672–4. (Dec 1992). doi:10.1038/360672a0. PMID 1465129.

- ^ “A mutation in APP protects against Alzheimer's disease and age-related cognitive decline”. Nature 488 (7409): 96–9. (Aug 2012). doi:10.1038/nature11283. PMID 22801501.

- ^ a b PDB: 1RW6; “The X-ray structure of an antiparallel dimer of the human amyloid precursor protein E2 domain”. Molecular Cell 15 (3): 343–53. (Aug 2004). doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2004.06.037. PMID 15304215.

- ^ “Structure and biochemical analysis of the heparin-induced E1 dimer of the amyloid precursor protein”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107 (12): 5381–6. (Mar 2010). doi:10.1073/pnas.0911326107. PMC 2851805. PMID 20212142.; see also PDB ID 3KTM

- ^ “Identification and transport of full-length amyloid precursor proteins in rat peripheral nervous system”. The Journal of Neuroscience 13 (7): 3136–42. (Jul 1993). PMID 8331390.

- ^ “Crystal structure of the N-terminal, growth factor-like domain of Alzheimer amyloid precursor protein”. Nature Structural Biology 6 (4): 327–31. (Apr 1999). doi:10.1038/7562. PMID 10201399.; see also PDB ID 1MWP

- ^ a b “Structural studies of the Alzheimer's amyloid precursor protein copper-binding domain reveal how it binds copper ions”. Journal of Molecular Biology 367 (1): 148–61. (Mar 2007). doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2006.12.041. PMID 17239395.; See also 2007 PDB IDs 2FJZ, 2FK2, 2FKL.

- ^ “Proteolytic processing and cell biological functions of the amyloid precursor protein”. Journal of Cell Science 113 (11): 1857–70. (Jun 2000). PMID 10806097.

- ^ “TMP21 is a presenilin complex component that modulates gamma-secretase but not epsilon-secretase activity”. Nature 440 (7088): 1208–12. (Apr 2006). doi:10.1038/nature04667. PMID 16641999.

- ^ “Amyloidogenic processing of the Alzheimer beta-amyloid precursor protein depends on lipid rafts”. The Journal of Cell Biology 160 (1): 113–23. (Jan 2003). doi:10.1083/jcb.200207113. PMC 2172747. PMID 12515826.

- ^ “Association of gamma-secretase with lipid rafts in post-Golgi and endosome membranes”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 279 (43): 44945–54. (Oct 2004). doi:10.1074/jbc.M407986200. PMC 1201506. PMID 15322084.

- ^ “Compartmentalization of beta-secretase (Asp2) into low-buoyant density, noncaveolar lipid rafts”. Current Biology 11 (16): 1288–93. (Aug 2001). doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00394-3. PMID 11525745.

- ^ “Notch and Presenilin: regulated intramembrane proteolysis links development and degeneration”. Annual Review of Neuroscience 26 (1): 565–97. (2003). doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.041002.131334. PMID 12730322.

- ^ “No hippocampal neuron or synaptic bouton loss in learning-impaired aged beta-amyloid precursor protein-null mice”. Neuroscience 90 (4): 1207–16. (1999). doi:10.1016/S0306-4522(98)00645-9. PMID 10338291.

- ^ “Inverse correlation between amyloid precursor protein and synaptic plasticity in transgenic mice”. NeuroReport 18 (10): 1083–7. (2007). doi:10.1097/WNR.0b013e3281e72b18. PMID 17558301.

- ^ “Relationships between expression of apolipoprotein E and beta-amyloid precursor protein are altered in proximity to Alzheimer beta-amyloid plaques: potential explanations from cell culture studies”. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology 67 (8): 773–83. (Aug 2008). doi:10.1097/NEN.0b013e318180ec47. PMC 3334532. PMID 18648325.

- ^ a b “Somatic APP gene recombination in Alzheimer's disease and normal neurons”. Nature 563 (7733): 639–645. (November 2018). doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0718-6. PMC 6391999. PMID 30464338.

- ^ “A peptide zipcode sufficient for anterograde transport within amyloid precursor protein”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103 (44): 16532–7. (Oct 2006). doi:10.1073/pnas.0607527103. PMC 1621108. PMID 17062754.

- ^ “Quantitative measurements and modeling of cargo-motor interactions during fast transport in the living axon”. Physical Biology 9 (5): 055005. (Oct 2012). doi:10.1088/1478-3975/9/5/055005. PMC 3625656. PMID 23011729.

- ^ “Iron and the translation of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) and ferritin mRNAs: riboregulation against neural oxidative damage in Alzheimer's disease”. Biochemical Society Transactions 36 (Pt 6): 1282–7. (Dec 2008). doi:10.1042/BST0361282. PMC 2746665. PMID 19021541.

- ^ “A synthetic peptide with the putative iron binding motif of amyloid precursor protein (APP) does not catalytically oxidize iron”. PLOS ONE 7 (8): e40287. (2012). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0040287. PMC 3419245. PMID 22916096.

- ^ “The amyloid precursor protein (APP) does not have a ferroxidase site in its E2 domain”. PLOS ONE 8 (8): e72177. (2013). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0072177. PMC 3747053. PMID 23977245.

- ^ “sAPP modulates iron efflux from brain microvascular endothelial cells by stabilizing the ferrous iron exporter ferroportin”. EMBO Reports 15 (7): 809–15. (Jul 2014). doi:10.15252/embr.201338064. PMC 4196985. PMID 24867889.

- ^ “Amyloid-beta precursor protein expression and modulation in human embryonic stem cells: a novel role for human chorionic gonadotropin”. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 364 (3): 522–7. (Dec 2007). doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.10.021. PMID 17959150.

- ^ “Differential processing of amyloid-beta precursor protein directs human embryonic stem cell proliferation and differentiation into neuronal precursor cells”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 284 (35): 23806–17. (Aug 2009). doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.026328. PMC 2749153. PMID 19542221.

- ^ “Opioid and progesterone signaling is obligatory for early human embryogenesis”. Stem Cells and Development 18 (5): 737–40. (Jun 2009). doi:10.1089/scd.2008.0190. PMC 2891507. PMID 18803462.

- ^ “The pregnancy hormones human chorionic gonadotropin and progesterone induce human embryonic stem cell proliferation and differentiation into neuroectodermal rosettes”. Stem Cell Research & Therapy 1 (4): 28. (2010). doi:10.1186/scrt28. PMC 2983441. PMID 20836886.

- ^ “DNA synthesis and neuronal apoptosis caused by familial Alzheimer disease mutants of the amyloid precursor protein are mediated by the p21 activated kinase PAK3”. The Journal of Neuroscience 23 (17): 6914–27. (Jul 2003). PMID 12890786.

- ^ “Luteinizing hormone, a reproductive regulator that modulates the processing of amyloid-beta precursor protein and amyloid-beta deposition”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 279 (19): 20539–45. (May 2004). doi:10.1074/jbc.M311993200. PMID 14871891.

- ^ a b c “Regulation of APP-dependent transcription complexes by Mint/X11s: differential functions of Mint isoforms”. The Journal of Neuroscience 22 (17): 7340–51. (Sep 2002). doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-17-07340.2002. PMID 12196555.

- ^ a b “The phosphotyrosine interaction domains of X11 and FE65 bind to distinct sites on the YENPTY motif of amyloid precursor protein”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 16 (11): 6229–41. (Nov 1996). doi:10.1128/mcb.16.11.6229. PMC 231626. PMID 8887653.

- ^ a b “Novel cadherin-related membrane proteins, Alcadeins, enhance the X11-like protein-mediated stabilization of amyloid beta-protein precursor metabolism”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 278 (49): 49448–58. (Dec 2003). doi:10.1074/jbc.M306024200. PMID 12972431.

- ^ “Interaction of a neuron-specific protein containing PDZ domains with Alzheimer's amyloid precursor protein”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 274 (4): 2243–54. (Jan 1999). doi:10.1074/jbc.274.4.2243. PMID 9890987.

- ^ “X11L2, a new member of the X11 protein family, interacts with Alzheimer's beta-amyloid precursor protein”. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 255 (3): 663–7. (Feb 1999). doi:10.1006/bbrc.1999.0265. PMID 10049767.

- ^ “Interaction of the phosphotyrosine interaction/phosphotyrosine binding-related domains of Fe65 with wild-type and mutant Alzheimer's beta-amyloid precursor proteins”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 272 (10): 6399–405. (Mar 1997). doi:10.1074/jbc.272.10.6399. PMID 9045663.

- ^ “Association of a novel human FE65-like protein with the cytoplasmic domain of the beta-amyloid precursor protein”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 93 (20): 10832–7. (Oct 1996). doi:10.1073/pnas.93.20.10832. PMC 38241. PMID 8855266.

- ^ “Molecular cloning of human Fe65L2 and its interaction with the Alzheimer's beta-amyloid precursor protein”. Neuroscience Letters 261 (3): 143–6. (Feb 1999). doi:10.1016/S0304-3940(98)00995-1. PMID 10081969.

- ^ “Interaction of cytosolic adaptor proteins with neuronal apolipoprotein E receptors and the amyloid precursor protein”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 273 (50): 33556–60. (Dec 1998). doi:10.1074/jbc.273.50.33556. PMID 9837937.

- ^ “APP-BP1, a novel protein that binds to the carboxyl-terminal region of the amyloid precursor protein”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 271 (19): 11339–46. (May 1996). doi:10.1074/jbc.271.19.11339. PMID 8626687.

- ^ “PAT1, a microtubule-interacting protein, recognizes the basolateral sorting signal of amyloid precursor protein”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 95 (25): 14745–50. (Dec 1998). doi:10.1073/pnas.95.25.14745. PMC 24520. PMID 9843960.

- ^ “Uncleaved BAP31 in association with A4 protein at the endoplasmic reticulum is an inhibitor of Fas-initiated release of cytochrome c from mitochondria”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 278 (16): 14461–8. (Apr 2003). doi:10.1074/jbc.M209684200. PMID 12529377.

- ^ “Human bleomycin hydrolase regulates the secretion of amyloid precursor protein”. FASEB Journal 14 (12): 1837–47. (Sep 2000). doi:10.1096/fj.99-0938com. PMID 10973933.

- ^ “Coordinated metabolism of Alcadein and amyloid beta-protein precursor regulates FE65-dependent gene transactivation”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 279 (23): 24343–54. (Jun 2004). doi:10.1074/jbc.M401925200. PMID 15037614.

- ^ “Caveolae, plasma membrane microdomains for alpha-secretase-mediated processing of the amyloid precursor protein”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 273 (17): 10485–95. (Apr 1998). doi:10.1074/jbc.273.17.10485. PMID 9553108.

- ^ “CLAC: a novel Alzheimer amyloid plaque component derived from a transmembrane precursor, CLAC-P/collagen type XXV”. The EMBO Journal 21 (7): 1524–34. (Apr 2002). doi:10.1093/emboj/21.7.1524. PMC 125364. PMID 11927537.

- ^ “Fibulin-1 binds the amino-terminal head of beta-amyloid precursor protein and modulates its physiological function”. Journal of Neurochemistry 76 (5): 1411–20. (Mar 2001). doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00144.x. PMID 11238726.

- ^ “Binding of gelsolin, a secretory protein, to amyloid beta-protein”. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 258 (2): 241–6. (May 1999). doi:10.1006/bbrc.1999.0623. PMID 10329371.

- ^ “An intracellular protein that binds amyloid-beta peptide and mediates neurotoxicity in Alzheimer's disease”. Nature 389 (6652): 689–95. (Oct 1997). doi:10.1038/39522. PMID 9338779.

- ^ “Tyrosine phosphorylation of the beta-amyloid precursor protein cytoplasmic tail promotes interaction with Shc”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 277 (19): 16798–804. (May 2002). doi:10.1074/jbc.M110286200. PMID 11877420.

- ^ “Interaction of reelin with amyloid precursor protein promotes neurite outgrowth”. The Journal of Neuroscience 29 (23): 7459–73. (Jun 2009). doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4872-08.2009. PMC 2759694. PMID 19515914.

関連文献

[編集]- “Regulation and expression of the Alzheimer's beta/A4 amyloid protein precursor in health, disease, and Down's syndrome”. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 695 (1 Transduction): 91–102. (Sep 1993). doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb23035.x. PMID 8239320.

- “Long time dynamic simulations: exploring the folding pathways of an Alzheimer's amyloid Abeta-peptide”. Accounts of Chemical Research 35 (6): 473–81. (Jun 2002). doi:10.1021/ar010031e. PMID 12069633.

- “A cell biological perspective on Alzheimer's disease”. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology 18 (1): 25–51. (2003). doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.18.020402.142302. PMID 12142279.

- “The beta-amyloid precursor protein (APP) and Alzheimer's disease: does the tail wag the dog?”. Traffic 3 (11): 763–70. (Nov 2002). doi:10.1034/j.1600-0854.2002.31101.x. PMID 12383342.

- “Pathogenic effects of cerebral amyloid angiopathy mutations in the amyloid beta-protein precursor”. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 977 (1): 258–65. (Nov 2002). doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04824.x. PMID 12480759.

- “Amyloid precursor protein (APP) and the biology of proteolytic processing: relevance to Alzheimer's disease”. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology 35 (11): 1505–35. (Nov 2003). doi:10.1016/S1357-2725(03)00133-X. PMID 12824062.

- “Cytoplasmic domain of the beta-amyloid protein precursor of Alzheimer's disease: function, regulation of proteolysis, and implications for drug development”. Journal of Neuroscience Research 80 (2): 151–9. (Apr 2005). doi:10.1002/jnr.20408. PMID 15672415.

- “Metals and amyloid-beta in Alzheimer's disease”. International Journal of Experimental Pathology 86 (3): 147–59. (Jun 2005). doi:10.1111/j.0959-9673.2005.00434.x. PMC 2517409. PMID 15910549.

- “The role of Abeta peptides in Alzheimer's disease”. Protein and Peptide Letters 12 (6): 513–9. (Aug 2005). doi:10.2174/0929866054395905. PMID 16101387.

- “The amyloid-beta precursor protein: integrating structure with biological function”. The EMBO Journal 24 (23): 3996–4006. (Dec 2005). doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7600860. PMC 1356301. PMID 16252002.

- “Physicochemical characteristics of soluble oligomeric Abeta and their pathologic role in Alzheimer's disease”. Neurological Research 27 (8): 869–81. (Dec 2005). doi:10.1179/016164105X49436. PMID 16354549.

- “New insights into potential functions for the protein 4.1 superfamily of proteins in kidney epithelium”. Frontiers in Bioscience 11 (1): 1646–66. (2006). doi:10.2741/1911. PMID 16368544.

- “Amyloidogenic processing of beta-amyloid precursor protein in intracellular compartments”. Neurology 66 (2 Suppl 1): S69–73. (Jan 2006). doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000192107.17175.39. PMID 16432149.

- “[Recurrent intraparenchimal haemorrhages in a patient with cerebral amyloidotic angiopathy: description of one autopsy case]”. Pathologica 98 (1): 44–7. (Feb 2006). PMID 16789686.

- “Does the p75 neurotrophin receptor mediate Abeta-induced toxicity in Alzheimer's disease?”. Journal of Neurochemistry 98 (3): 654–60. (Aug 2006). doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03905.x. PMID 16893414.

- “APP processing and the APP-KPI domain involvement in the amyloid cascade”. Neuro-Degenerative Diseases 2 (6): 277–83. (2006). doi:10.1159/000092315. PMID 16909010.

- “Dysfunction of amyloid precursor protein signaling in neurons leads to DNA synthesis and apoptosis”. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1772 (4): 430–7. (Apr 2007). doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2006.10.008. PMC 1862818. PMID 17113271.

- “Mitochondrial dysfunction and Alzheimer's disease”. Current Alzheimer Research 3 (5): 515–20. (Dec 2006). doi:10.2174/156720506779025215. PMID 17168650.

- “Focal adhesions regulate Abeta signaling and cell death in Alzheimer's disease”. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1772 (4): 438–45. (Apr 2007). doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2006.11.007. PMC 1876750. PMID 17215111.

- “When loss is gain: reduced presenilin proteolytic function leads to increased Abeta42/Abeta40. Talking Point on the role of presenilin mutations in Alzheimer disease”. EMBO Reports 8 (2): 136–40. (Feb 2007). doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400896. PMC 1796780. PMID 17268504.

外部リンク

[編集]- GeneReviews/NCBI/NIH/UW entry on Early-Onset Familial Alzheimer Disease

- Amyloid Protein Precursor - MeSH・アメリカ国立医学図書館・生命科学用語シソーラス

- Entrez Gene: APP amyloid beta (A4) precursor protein (peptidase nexin-II, Alzheimer disease)

- Human APP genome location and APP gene details page in the UCSC Genome Browser.